Chapter 18 Laparoscopic Pancreatoduodenectomy

Recent advances in technology and surgical techniques have allowed a wide range of applications of minimally invasive surgery to be applied in patients with benign and malignant diseases of the pancreas. Whereas laparoscopic resection of the distal pancreas requires no anastomosis and therefore has gained worldwide acceptance (described in Chapter 23 of the Atlas of Minimally Invasive Surgery, 2009; see Suggested Readings at the end of this chapter), excision of cephalic lesions by minimal access techniques remains an underused approach because of its technical complexity and prolonged surgery.

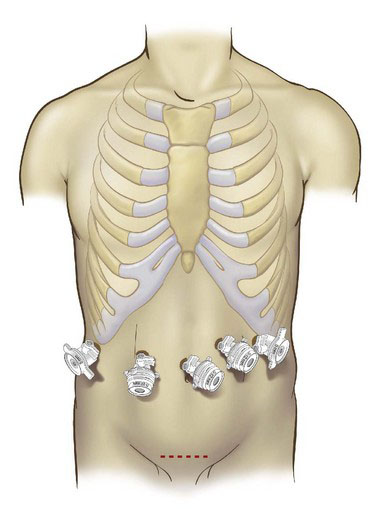

Patient positioning and placement of trocars

All patients receive preoperative deep venous prophylaxis including thromboembolism-deterrent stockings and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) unless epidural anesthesia is contemplated, in which case LMWH is administered after insertion of the epidural catheter and intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis. The surgery is carried out under general anesthesia, and patients receive epidural anesthesia selectively. The patient is placed in a flat Lloyd-Davies (French) position, with the surgeon standing between the patient’s legs and the assistant on the patient’s right or left according to the steps of the procedure. Most of the surgery is carried out with the patient in a 30-degree reverse Trendelenburg position to allow the colon and omentum to drop away from the upper abdomen. Surgery is most commonly conducted using a completely laparoscopic approach, although a recent review of the literature revealed that one fourth of the procedures were carried out using a hand-assist approach. The pneumoperitoneum is established and maintained at 12 to 15 mm Hg. The procedure may employ five trocars, as shown in Figure 18-1. A 30-degree laparoscope is employed routinely. The liver is retracted in a cephalad direction using an 80-mm angled Diamond-Flex retractor, which is fixed in position using a table clamp (Fast Clamp, Snowden-Pencer, San Diego, Calif.).

Operative technique

Resection

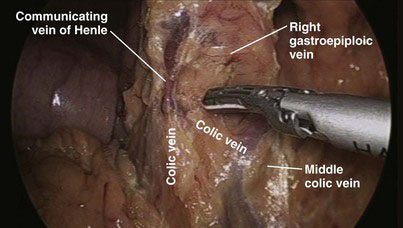

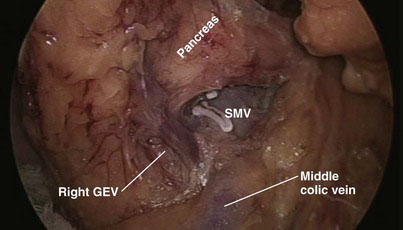

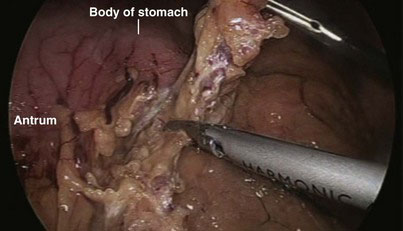

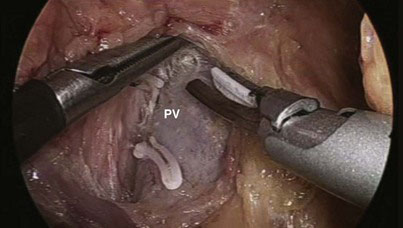

Most of the steps and principles of the resection and reconstruction of the LPD are the same as those in open surgery. After an exploratory laparoscopy, the gastrocolic omentum at the antrum and distal body of the stomach is divided with the ultrasonically activated scalpel (UAS), and the lesser sac is entered. With the posterior aspect of the antrum held and retracted upward by the assistant through the patient’s leftmost lateral 5-mm port, any adhesions between the stomach and the anterior surface of the pancreas are divided. The transverse colon is then mobilized off the anterior surface of the pancreas and the second and third portions of the duodenum; early in this process is the division of the communicating vein of Henle between the middle colic and right gastroepiploic veins (Fig. 18-2), which allows the transverse colon to fall away from the head of the pancreas and facilitates exposure of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). Also, the right gastroepiploic vessels are encountered at the inferior border of the first part of the duodenum and their division (especially that of the vein, Fig. 18-3) enhances access to the SMV; the most superficial of these, the vein, is first dissected off its confluence with the SMV and divided between locking clips (Hem-o-lok, Weck Closure Systems, Research Triangle Park, N.C.). The artery that lies in a deeper position could be similarly clipped and divided if necessary. Identification of the SMV is facilitated by following the colic vein or the right gastroepiploic vein and by gentle mobilization of the inferior border of the body of the pancreas toward the neck, where the SMV can also be encountered. The anterior surface of the SMV is dissected and followed in a cephalad direction behind the neck of the pancreas to expose the confluence with the splenic vein and to further dissect the anterior surface of the portal vein and confirm resectability (Fig. 18-4).

FIGURE 18-4 The portal vein (PV) and the superior mesenteric vein were dissected to confirm resectability.

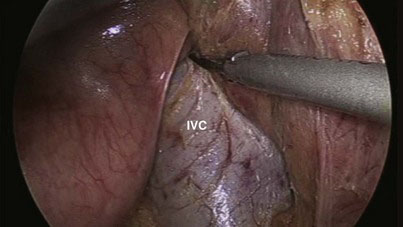

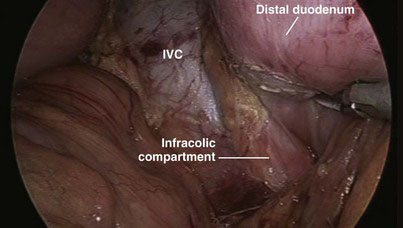

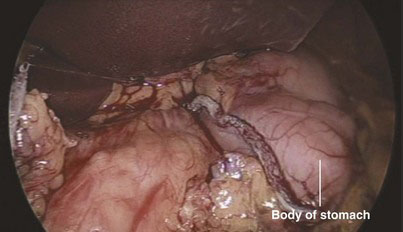

If necessary, the hepatic flexure of the colon may be taken down to enhance exposure of the duodenum, although we have not found this step always necessary. The duodenum is extensively kocherized, exposing the inferior vena cava and left renal vein (Fig. 18-5) until the territory of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is reached, and separating the third and, if possible, the fourth parts of the duodenum from the transverse mesocolon until the infracolic compartment is reached (Fig. 18-6). In preparation for division of the antrum, the right gastroepiploic vessels are divided between locking clips along the inferior border of the junction between the antrum and body of the stomach (Fig. 18-7), and the vessels along the lesser curvature of the stomach in the region of the incisura and the lesser omentum are also divided with the UAS. The gastric antrum is then divided with endostaplers (Fig. 18-8) after ensuring that the nasogastric and nasojejunal tubes have been advanced no further than 50 cm. To avoid oozing from the staple line that could later obscure the operative field, we tend to oversew the distal staple line for hemostasis and to control the proximal staple line with the Harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, Ohio), which will be incorporated in a suture line later when the gastrojejunostomy is constructed, and to wrap it with gauze. The body of the stomach is then pushed into the left upper quadrant to facilitate exposure of the hepatic artery.

FIGURE 18-5 Kocherization of the duodenum and exposure of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and left renal vein.

FIGURE 18-6 The distal duodenum was mobilized until the infracolic compartment was reached. IVC, inferior vena cava.

FIGURE 18-8 The stomach has been transected with staplers at the junction between its body and antrum.

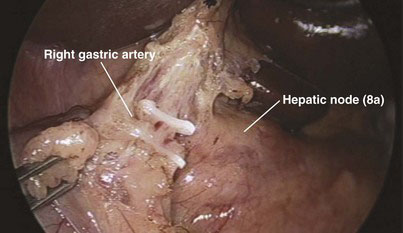

The peritoneum over the anterior surface of the hepatoduodenal ligament is then divided from left to right until its aspect over the upper border of the Calot triangle is also divided. With the assistant holding and retracting the antrum of the stomach caudally, dissection along the left border of the hepatoduodenal ligament allows for identification of the right gastric artery, which is then clipped and divided (Fig. 18-9). This allows the antrum of the stomach to fall away from the hepatoduodenal ligament and facilitates the dissection of the gastroduodenal artery. Dissection with the Harmonic scalpel then proceeds between the lower border of the common hepatic artery and the upper border of the body of the pancreas and duodenum. Group 8a (anterior hepatic) lymph nodes could be dissected off at this stage, mobilized off the common hepatic artery from left to right, and kept attached to the upper border of the head of the pancreas or removed separately for histologic analysis. Alternatively, this group of lymph nodes could be dissected before division of the neck of the pancreas (see the accompanying DVD as well as Expert Consult). This will lead to exposure of the gastroduodenal artery, which after meticulous dissection is mobilized (Fig. 18-10A), double-clipped, and divided with scissors (Fig. 18-10B). Holding the proximal stump of the gastroduodenal artery, the surgeon can mobilize the hepatic artery further in a cephalad direction. Division of the neurolymphatics in this region exposes the anterior surface of the portal vein and the left border of the common bile duct.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree