![]() Access the accompanying videos for this chapter online. Available on ExpertConsult.com .

Access the accompanying videos for this chapter online. Available on ExpertConsult.com .

Adnexal structures in females include the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and ligaments that support their association with the uterus. Congenital and acquired conditions including benign and malignant diseases can develop at all points in a female’s lifespan. Laparoscopy remains the ideal choice for operative access to diagnosis and treatment of adnexal diseases and disorders. It has the advantages of being a safe, cost-effective, and minimally invasive approach. Numerous studies have supported the advantages of decreased blood loss, return to productivity, and diminished adhesion formation in adolescents.

Access to the adnexa is usually initiated using the umbilicus for placement of the telescope and camera with lateral accessory ports inserted depending on the findings at operation. Occasionally, large masses or a history of previous operations requires the use of the left upper quadrant or alternative abdominal wall sites for the initial entry.

Increasing emphasis has been placed on conservative surgery for benign disease in the adnexa whenever safe and possible. Fertility-sparing and -enhancing techniques, including gentle manipulation of the fallopian tubes, adhesiolysis, and anatomically restorative procedures of the ovary along with avoidance of oophorectomy, are now appreciated as important in managing adnexal conditions. Oophorectomy, particularly for benign conditions, is associated with adverse reproductive outcomes and diminished fertility reserve as well as an earlier onset of menopause.

Most adnexal masses in girls younger than the age of 21 are categorized as either benign or congenital masses. Malignant neoplasms make up around 5% of all masses, but the incidence is influenced by age, the internal characteristic architecture of the mass, the presence of malignant serum markers, and the size of the mass.

While there is no absolute clinical tool to preoperatively diagnose all adnexal masses, several algorithms are being proposed to stratify those that likely represent a malignant process. By utilizing radiologic and serum markers of malignancy, laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy can be utilized for benign cystic diseases more efficiently, thereby allowing for fertility sparing. One study using preoperative characteristics of complexity of the mass on imaging and a size greater than or equal to 8 cm reduced the number of benign lesions treated with laparotomy while ensuring malignant masses were managed appropriately. More extensive operative approaches with oophorectomy and associated staging procedures can then be reserved for those cases that are likely malignant.

Operative Technique

Ovarian Cystectomy

Indications

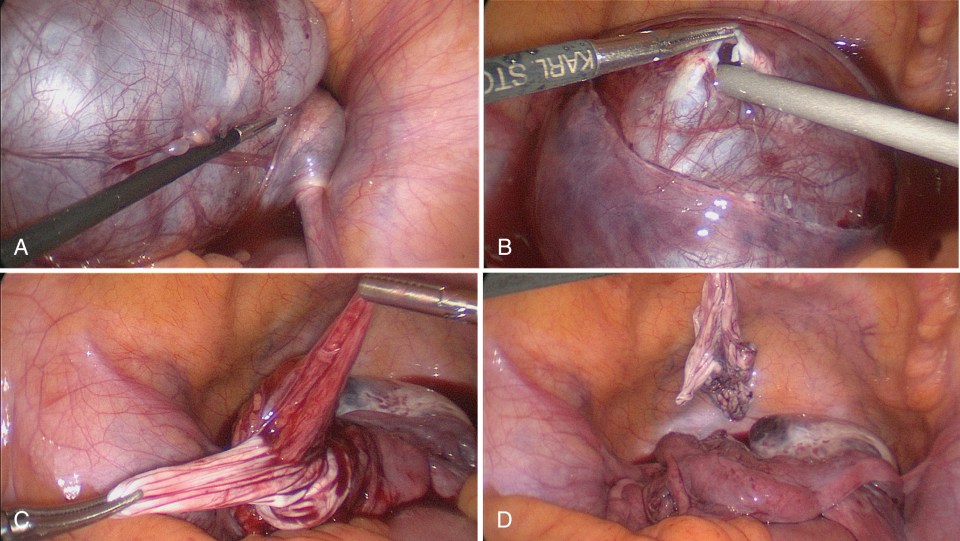

Benign adnexal cysts and tumors in children and adolescents range from stromal tumors to epithelial tumors, though the most common types are functional cysts, such as hemorrhagic or follicular, and benign germ cell tumors. The most common germ cell tumor is a benign ovarian teratoma ( Fig. 21-1A ). Teratomas usually present with classic features on imaging, such as the appearance of hypoechoic fluid or hyperechoic lesions suspicious for calcification. Other features include the presence of fat or hair. A small proportion of these cysts can present with neural tissue as well. There is also a special circumstance in which patients with these teratomas can present concurrently with psychological changes and paraneoplastic encephalitis with neural mediated anti-N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. In such patients, since the tumor is the source of these receptors, it is imperative that the teratoma is removed once the diagnosis is established, with the expected gradual return to the patient’s psychological baseline and resolution of the encephalitis in most cases. The most important point to appreciate is that, in the setting of negative tumor markers (α-fetoprotein [AFP], lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], human chorionic gonadotropin [HCG], cancer antigen 125 [CA125]), most germ cell tumors can be approached laparoscopically. Additional markers (estradiol, inhibin, carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA], testosterone) can be useful when making decisions about cystectomy versus oophorectomy if the history and imaging suggests a different tumor type.

Traditional Operative Technique

When functional cysts are encountered at laparoscopy, these can be drained or incised, or the cyst wall can be completely removed. When benign cysts or tumors are found, the goal is to remove the cyst completely to avoid leaving tumor behind and to avoid recurrence. The ovarian cortex is incised with cautery to expose the cyst wall beneath it. With careful dissection, the cyst can be fully exposed, while also paying attention to any vessels requiring coagulation ( Fig. 21-1B through 21-1D ). Ideal instruments to accomplish this excision include bipolar or monopolar cautery, but also having access to a vessel-sealing device such as a Harmonic Scalpel (Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH) or Ligasure (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) or the 3-mm vessel sealer (Bolder Surgical, Louisville, CO) is helpful as well.

Special Considerations

- 1.

Approach to the large adnexal mass

In the patient with a large adnexal mass ( Fig. 21-2 ) that is expected to be benign, there are several strategies for management. First, it is helpful to place three to four ports with at least two ports located cephalad on the abdominal wall. Positioning the telescope/cannula port supraumbilically and another port in the left upper quadrant can lead to improved visualization as the camera can then be positioned at the most cephalad point on the abdominal wall to better see around the mass. It can be helpful to dissect the cyst off the ovary or mesosalpinx before draining the cyst because the tissue planes are better visualized with an intact cyst. Then the cyst can be mobilized to the umbilicus for drainage. Placing a pursestring suture around the planned drain site helps keep the mass somewhat distended, if needed, to continue to develop the tissue planes in order to fully separate the mass from the ovary.

Alternatively, the cyst can be separated from the ovarian cortex and drained, and the cyst wall stripped away from the cortex ( Fig. 21-3 ). With either technique, once the mass has been separated from the ovary or fallopian tube, the cyst wall can be placed in an endoscopic retrieval bag. If the mass is not decompressed enough once in the bag, the mass can be further drained within the bag and the bag delivered to the umbilicus. Additional tissue morcellation within the bag can then occur, if needed, to remove the cyst wall completely through a small umbilical incision.

- 2.

Teratoma with spill

As previously mentioned, it is ideal for an ovarian cyst to remain intact during the dissection as this aids in distinguishing tissue planes between the cyst and normal ovary. However, rupture of the cyst/tumor cannot always be avoided and occurs in approximately 50% of cases. One study looked at rupture among ovarian teratomas due to the concern for chemical peritonitis caused by the rupture. In comparing cysts that ruptured, whether performed open or laparoscopically, no patients in which rupture occurred developed peritonitis postoperatively. When a dermoid cyst of the ovary ruptures, the surgeon should continue removing the cyst wall, but the surgeon should also copiously irrigate the abdomen and pelvis. Sometimes, it is necessary to irrigate three or four times to eliminate the oily/fatty fluid and hair within the abdomen and pelvis.

Oophorectomy

Oophorectomy (with or without removal of the fallopian tube) is discouraged in pediatric and adolescent patients as fertility-sparing options are preferred in most cases. Indications for oophorectomy include a high suspicion of malignant disease or previous confirmation of malignancy on biopsy or frozen section, or as a prophylactic measure in females with certain differences in sexual development (DSD) disorders.

While the laparoscopic approach is favored for benign conditions, when malignant masses are suspected or confirmed, open abdominal or, increasingly, robotic operations are being used to manage these conditions. Pediatric oncology protocols recommend fertility preservation, if at all possible, in girls with documented malignancy, with unilateral oophorectomy, and uterine-sparing procedures. Frozen section biopsy is imperative for suspicion of bilateral malignant disease prior to bilateral oophorectomy, which would result in infertility.

Recommendations for oophorectomy among individuals with DSD, especially in the presence of a Y chromosomal makeup, have been advocated, although timing and appropriateness are being reconsidered, particularly with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS). Also, with advances in fertility-sparing techniques, oophorectomy for subsequent cryopreservation is being done under experimental protocols on prepubertal girls, and in postpubertal girls who lack the time required for egg stimulation and freezing protocols.

When indicated, oophorectomy can be accomplished via a laparoscopic approach, allowing for tissue removal in an endoscopic retrieval bag through an expanded port incision. Morcellation techniques with the specimen in the bag are sometimes needed to reduce the size of the incision, but uncontrolled morcellation is discouraged due to possible tumor spread. Vascular control of the ovarian artery and vein can be accomplished with advanced sealing energy systems designed for large vessels or with stapling devices. However, it is important to dissect the artery and vein after opening the broad ligament and to ligate these vessels individually to avoid a retroperitoneal hematoma and hemorrhage. The course of the ureter from the pelvic brim into the pelvis should be identified to avoid a high ureteral injury or transection as it courses toward the vascular pedicle. When oophorectomy is performed for malignancy, the fallopian tube is removed most commonly en bloc with the ovary.

Special technical considerations for oophorectomy when done for cryopreservation reasons include initiating the dissection at the utero-ovarian ligament, sparing vascular injury to the ovary as much as possible, and retaining the fallopian tube to possibly enhance subsequent fertility. Removal of dysgenetic gonads in individuals with DSD may require higher ligation of the vessels and biopsy of the surrounding tissue to ensure complete removal ( Fig. 21-4 ).