Chapter 37 Laparoscopic Myomectomy

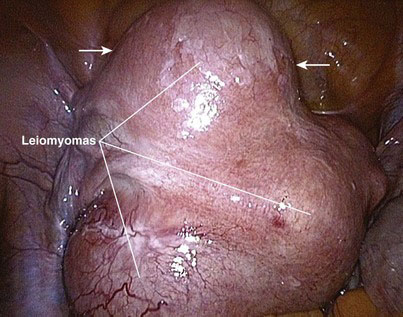

A myoma is a benign solid tumor consisting of fibrous tissue; hence, it often is called a fibroid tumor. A uterine leiomyoma, or fibroid, refers to a fibrous uterine tumor of smooth muscle origin. A leiomyoma is a well-circumscribed, round solid tumor, pearly white or light tan in color, that may grow as a single nodule or in clusters of varying size. This tumor may be attached to or be within the myometrium and is pseudoencapsulated by fibrous connective tissue. The diameter of a leiomyoma may range from 1 mm to more than 30 cm (Fig. 37-1).

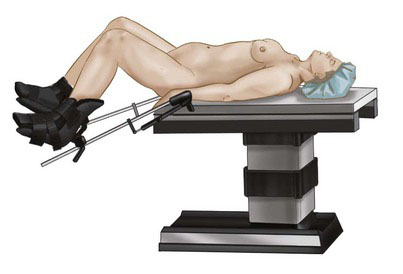

Patient positioning in the operating suite

Under general endotracheal anesthesia, the patient is positioned in lithotomy position with arms tucked at the sides to allow for surgeon mobility and to avoid brachial plexus injury (Fig. 37-2). A Foley catheter is placed. Two video monitors are placed at the foot of the bed. The cervix is grasped with a tenaculum and dilated with Hegar cones, and a uterine manipulator is inserted to assist with exposure and removal of the myomas. The surgeon stands on the patient’s left, the first assistant stands to the right, and the second assistant is between the legs. A Veress needle is inserted at the umbilicus, and the abdomen is insufflated with carbon dioxide to a pressure of 18 mm Hg.

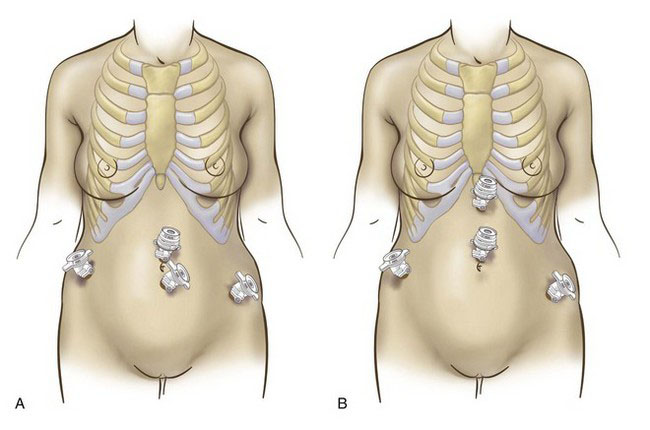

Positioning and placement of trocars

A 10-mm optical trocar is inserted at the umbilicus, and the laparoscope is placed through this port (Fig. 37-3A). Two 5-mm trocars are inserted in the lower abdomen, lateral to the inferior epigastric arteries. A third 5-mm trocar is inserted in the midline, level with or higher than the first two. If the patient has a large myoma that extends toward the umbilicus, then the surgeon may consider an open supraumbilical abdominal entry to establish pneumoperitoneum (Fig. 37-3B). The midline operative port then should be placed through the umbilicus or even higher. In the presence of large pathology, the optimal insertion points for the lateral 5-mm trocars can be determined after laparoscopic inspection of the pelvis.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree