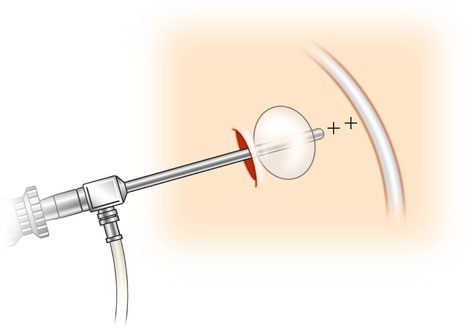

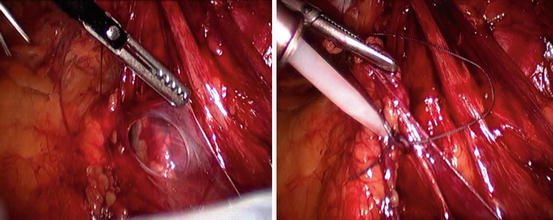

Fig. 6.1

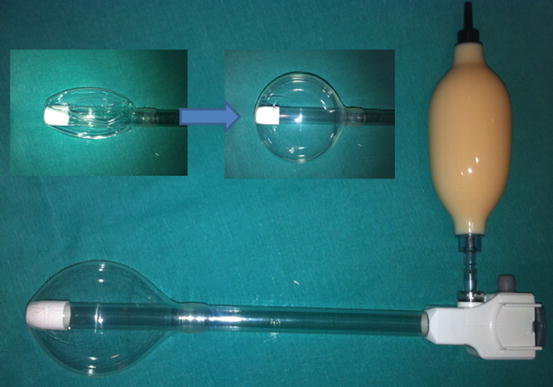

Instruments in TEP technique

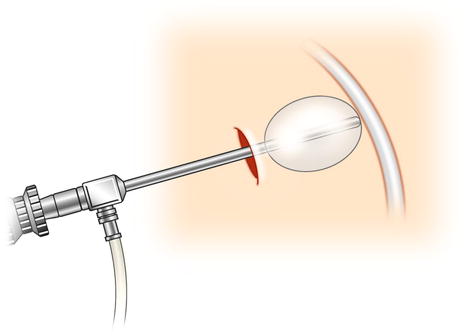

Additionally, and in order to create more preperitoneal space, we will use a PDB balloon trocar and subsequently a 12-mm BTT structural trocar. See Figs. 6.2 and 6.3. The mesh and the fixation method used will be dealt with in other chapters.

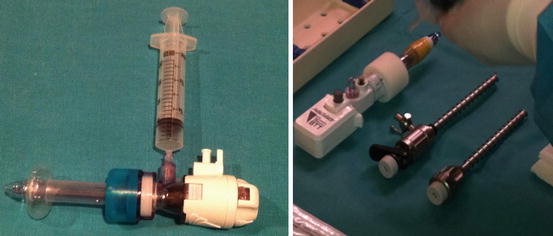

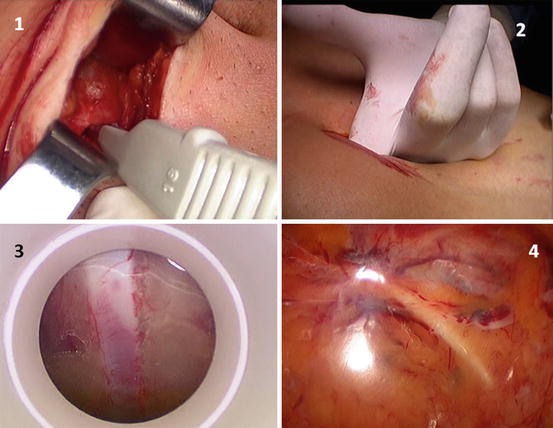

Fig. 6.2

PDB trocar

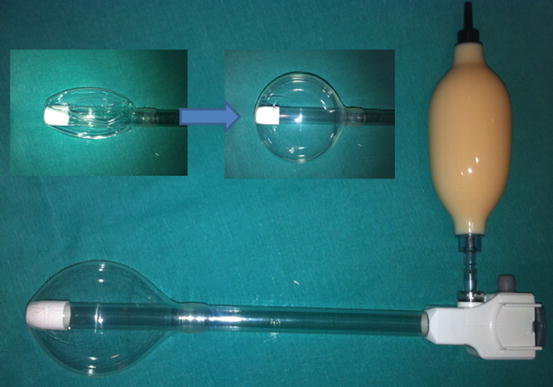

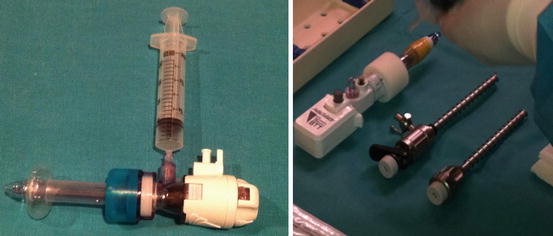

Fig. 6.3

BTT trocar and 5-mm trocars

Surgical Technique

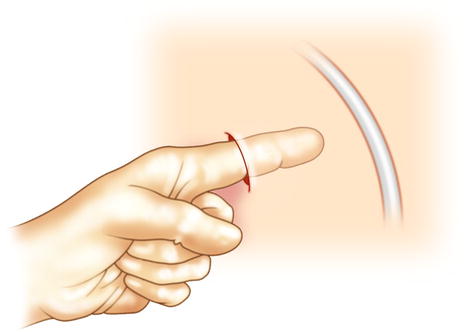

Incision

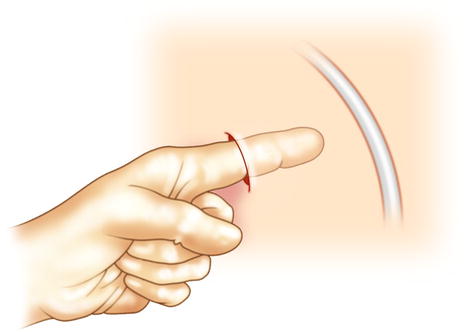

The first technical movement is a 2-cm horizontal incision in the subumbilical region. After dissection of the subcutaneous cellular tissue, the superficial aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis muscle homolateral to the hernia is exposed. A 2-cm opening is made parallel to the direction of the muscle with the index finger and blunt dissection, and all of the rectus abdominis muscle is turned back, creating a retro muscular tunnel. See Fig. 6.4.

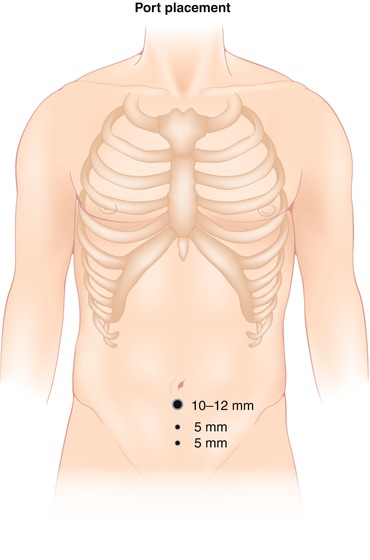

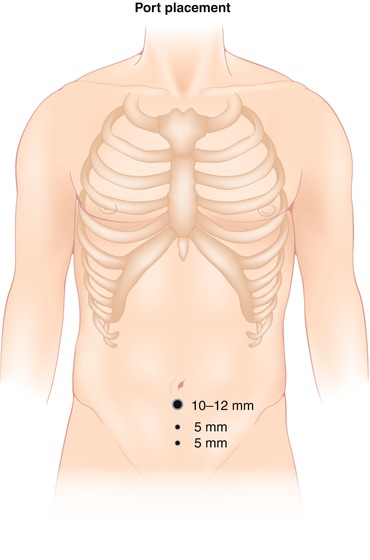

Fig. 6.4

Port placement

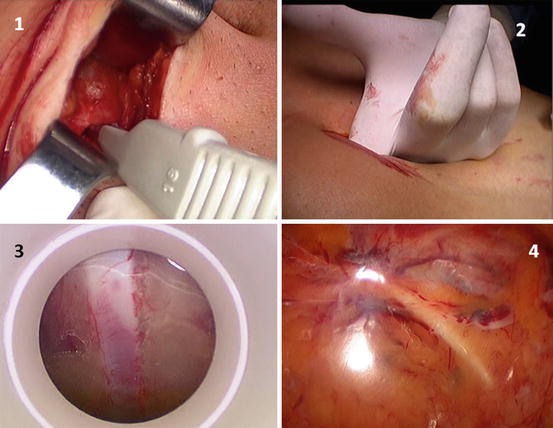

Creation of the Preperitoneal Space

Once this step has been carried out, the PDB balloon trocar is introduced and progressively inflated, achieving the opening of the entire preperitoneal space at the same time as the balloon is filled. The optic is introduced through the trocar in order to confirm the correct positioning of the balloon and begin structural identification. With alternating lateral movements of the optic introduced in the trocar, an opening in the Retzius space is achieved and more laterally in the Bogros’ space. Subsequently, the balloon trocar is removed and the BTT trocar is put into place. After the establishment of the pre-pneumoperitoneum, two 5-mm trocars are placed on the infraumbilical midline separated by approximately 5 cm, under direct view. See Figs. 6.5, 6.6, 6.7, and 6.8.

Fig. 6.5

Rome dissection with the finger until the Cooper’s ligament

Fig. 6.6

6 PDB balloon trocar makes the preperitoneal dissection

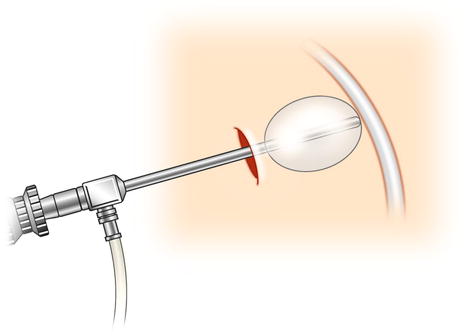

Fig. 6.7

BTT trocar and two infraumbilical 5-mm trocar

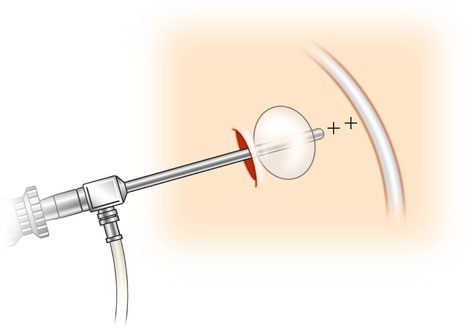

Fig. 6.8

Technique to open the Retzius space in TEP. 1 Opening the anterior fascia of rectus muscle, 2 Dissection with the finger the preperitoneal space, 3 PDB trocar: epigastric vessels, 4 PDB trocar: Cooper’s ligament and epigastric vessels

Identification of Structures

It is necessary to identify the inferior epigastric vessels which are found in the most cranial area of the working space and Cooper’s ligament. This ligament is easily recognized as it is pearly white and in the medial zone above the bladder. Once these structures have been identified, we should also be able to view the inguinal cord and the iliac vessels, which are found below and more medial to the cord.

Reduction of the Hernial Sac

In the case of a direct hernia occurring, the sac is generally completely reduced when the preperitoneal space is created with the PDB trocar, with one being able to see an orifice in the posterior wall of the inguinal region medial to the epigastric vessels, which is the direct orifice. In the case of it not being reduced in this manner, with simple traction of the sac in an inferior direction, it will be completely reduced, allowing a view of the transversalis fascia over the direct inguinal orifice. If the patient has an indirect hernia, the sac accompanies the elements of the cord (gonadal vessels and the vas deferens) for its most cranial and media portions. Using traction and contra-traction maneuvers, we will achieve the total reduction of the indirect sac, making sure at all times that we do not traction over the gonadal vessels or the vas deferens in order to avoid lesions.

The reduction of both direct and indirect sacs finalizes when we completely skeletized the inguinal cord and we see the iliopsoas muscle, the caudal margin of the dissection.

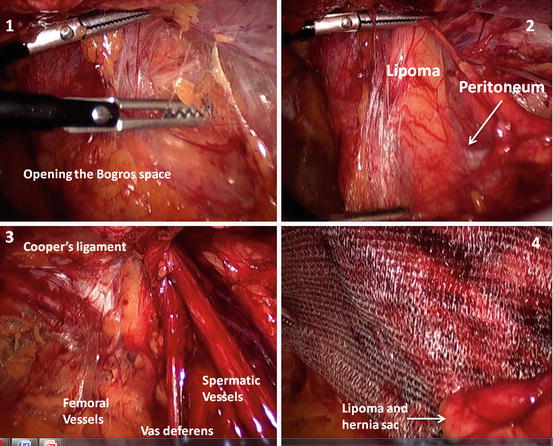

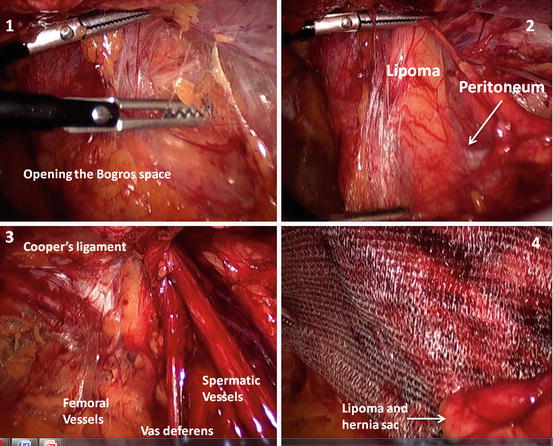

Opening of the Bogros’ Space

Once the hernial sac has been reduced and the inguinal elements have been skeletonized, it is necessary to continue the lateral dissection, finalizing the opening of the Bogros’ space. Laterally turning down the peritoneum, it is possible to reach the anterior superior iliac spine, the lateral margin of the dissection. During this step, it is common to observe nerve structures such as the femoral nerve and the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve, which need to be avoided in order to rule out chronic pain in the inguinal region.

Introduction of the Mesh

The prosthesis is rolled up and inserted through the BTT trocar and is unrolled in the preperitoneal space. A consensus exists among the surgical community as to the minimum size of the mesh to be used. This should be a minimum of 10 × 15 cm in order to reinforce all the possible hernial orifices (direct, indirect, and femoral). The positioning of the mesh in the said space is vital in order to avoid an early recurring hernia, and for this reason we will give special attention to this step. It should totally surpass Cooper’s ligament and the pubis (even more so in the case of direct hernias), covering adequately the inguinal cord and the deep inguinal orifice and reaching the most lateral area of the Bogros’ space. See Fig. 6.9.

Fig. 6.9

Introducing the mesh. 1 Opening the Bogros space, 2 Reduction of the hernia (lipoma and the sac), 3 Identify the structures, 4 Mesh placement: the lipoma and the hernia sac are placed against the mesh

Prosthetic Fixation

For prosthetic fixation in the preperitoneal space, we can use different methods: absorbable or nonabsorbable tackers, glues, biological glues, or even no fixation method. The indication of one or another method will be discussed in another chapter.

Evacuation of the Pre-pneumoperitoneum and the Closure of Trocars

Evacuation of CO2 must be done slowly, without moving the mesh during this stage, at all times observing with the optic. Simultaneously, it is convenient at this time to evacuate the CO2 that could have been retained in both scrotal regions by diffusion throughout this operation. Once the pre-pneumoperitoneum has been evacuated, the surgery is completed with the closure of the superficial aponeurosis orifice and the incisions in the skin.

Complications

The complications which can arise in a laparoscopic hernioplasty inguinal TEP procedure can be classified into the categories discussed in the following sections.

Intraoperative

Hemorrhage

Few hemorrhages occur during a TEP procedure, and those which do are easily controlled with cauterization. Lesions on the inferior epigastric vessels, the obturator artery, or collateral arteries are produced by inadequate traction and are controlled using metal clips. Hemorrhage from iliac vessels is incidental.

Damage to the Inguinal Cord

Lesions of the vas deferens are rare due to the easy identification of this medial structure to the inguinal cord, which appears as a pearly white cord. The gonadal vessels are situated posterior and lateral to the inguinal cord, underneath the indirect hernial sac. In order to avoid lesions to both structures, it is essential to achieve a precise identification, separating them from the indirect hernial sac with smooth maneuvers, avoiding excessive tractions.

Peritoneal Rupture

This is the most frequent complication, with an incidence rate of between 13 and 24 %, and in 7 % of patients the tear is massive, losing the preperitoneal space and therefore forcing a TAPP approach or open surgery. The surgeon’s experience is vital in order to maintain a low conversion rate.

The best way of avoiding this complication is to identify at all times the peritoneum margin and the hernial sac, carrying out traction and contra-traction maneuvers in a smooth manner.

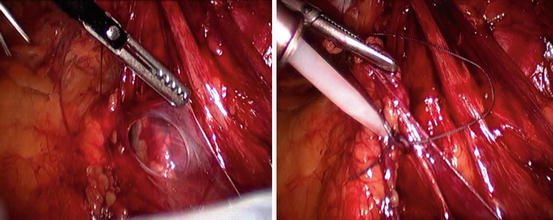

Although various studies with positive results have been published in which the peritoneal small defect is not closed [4], we believe that in all of the cases in which a peritoneal rupture is identified, it is recommendable to close it in order to avoid the loss of the CO2 in the intraperitoneal cavity and the consequent diminishing of the work space, as well as to reduce the probability of an introduction of a bowel loop through the orifice and the immediate postoperative appearance of an obstruction.

There are several methods of peritoneal closure, such as continuous suturing, the use of clips, or the use of preformed loops (Endoloops®, Ethicon endosurgery, Blue Ash, OH, USA). This last option is the quickest and simplest. See Fig. 6.10.

Fig. 6.10

Closure of peritoneal tear with Endoloops (Endoloop®, Ethicon Endosurgery, Blue Ash, OH, USA)

In the case of a loss of the pre-pneumoperitoneum in the intraperitoneal cavity which produces a slight reduction of the working space, we can increase this space with the introduction of a Veress needle in the left hypochondrium, facilitating the exit of intraperitoneal CO2.

Postoperative

Seroma

This is the most common postoperative complication, above all in patients with direct or medial hernias. It appears as a non-painful lump in the inguinal region, from the 4th or 5th day post-operation, starting with a soft consistency and afterwards a hard consistency. During examination, it does not reduce or change with pressure or when lying down. It does not require treatment and usually disappears approximately 1 month after the operation. Only in those symptomatic cases and those in which it does not disappear can puncture aspiration be recommended.

Various techniques have been published in order to diminish the incidence of seromas. In the case of direct hernias, we can invaginate the transversalis fascia, fixing it to Cooper’s ligament with a helicoidal suture or by using an Endoloop. If we come across large direct hernias, it would be recommendable to completely reduce the hernial sac, as this has been shown to reduce the incidence of seromas. If it is not possible to completely reduce it, once the sac is selected and bound to the nearest ending, we can fix the distal end of the sac to the posterior wall of the inguinal region in order to diminish the dead space which would remain if we were to leave it without fixing it.

Scrotal Hematoma

This complication is usually quite frequent in patients who have been operated on for an inguinoscrotal hernia, with an incidence rate of between 4 and 22 % according to publications. The treatment is conservative with relative rest and anti-inflammatories. Only in those cases showing an organized hematoma, clinically very symptomatic, should this be surgically drained.

To avoid this complication, it is necessary to carry out a careful dissection and hemostasis during the surgical procedure, above all in those patients with inguinoscrotal hernias and those patients receiving an anticoagulant treatment. In these cases, the use of aspirational drainage can help to diminish the incidence of scrotal hematomas.

Ischemic Orchitis

The appearance of pain or testicular inflammation in the first 5 days after the operation should make us consider ischemic orchitis. Its incidence varies between 0.05 and 0.1 %, above all in patients with inguinoscrotal hernias with a larger dissection of the hernial sac. It is believed that it is due to a thrombosis of the pampiniform venous plexus more than an arterial lesion and should be differentiated from a scrotal hematoma or testicular torsion. A scrotal ultrasound helps with diagnosis, and treatment is based on anti-inflammatories, relative rest, and scrotal suspensory. The majority of patients recover completely without developing testicular atrophy.

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is that which persists for longer than the third month after surgery. The following have been confirmed through evidence-based medicine:

1.

The laparoscopic approach to inguinal hernias produces less acute and chronic pain than conventional surgery (1A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree