Chapter 36 Laparoscopic Hysterectomy for Benign Conditions

Procedures

Types of Laparoscopic Hysterectomy

A hysterectomy for benign disease may be performed laparoscopically from beginning to end. In total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH), all of the steps, including the division of the uterine ligaments, vaginal cuff incision (colpotomy), and vaginal cuff closure, are accomplished through the laparoscope, and the specimen usually is removed from the vagina. If the uterus is too large, then morcellation may be performed with a specialized morcellator, or by simply cutting the specimen into smaller components with conventional instruments. If laparoscopy is used as an adjunct to VH, then this procedure is considered a laparoscopy-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH). The American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists has standardized the terminology for minimally invasive hysterectomy (Tables 36-1 and 36-2). Based on this classification, TLH is considered a type IVE procedure. Some surgeons have promoted preservation of the cervix and perform a laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH).

Table 36-1 Classification System for Laparoscopic Hysterectomy

| Type | Laparoscopic Component of Hysterectomy |

|---|---|

| 0 | Laparoscopy-directed preparation for vaginal hysterectomy, including adhesiolysis and/or excision of endometriosis |

| I | Occlusion and division of at least one ovarian pedicle, uteroovarian ligament, or infundibulopelvic ligament, but not the uterine artery |

| II | Type I plus occlusion and division of one or both uterine arteries |

| III | Type II plus a portion, but not all, of the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex, unilateral or bilateral |

| IV | Complete detachment of the cardinal-uterosacral complex, unilateral or bilateral, with or without entry into the vagina. This category includes total laparoscopic hysterectomy. |

Adapted from Olive DL, Parker WH, Cooper JM, et al: The AAGL classification system for laparoscopic hysterectomy. Classification Committee of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 7:9–15, 2000.

Table 36-2 Subgroup Classification System for Laparoscopic Hysterectomy

| Subgroup | Step Completed Laparoscopically |

|---|---|

| A | Cases limited to the division of the pedicle(s) containing ovarian or uterine vessels |

| B | Cases that include dissection of the bladder |

| C | Cases that include performance of a posterior colpotomy |

| D | Cases that include both bladder dissection and a posterior colpotomy |

| E | Applies only to type IV laparoscopic hysterectomies and is reserved for total laparoscopic hysterectomies |

Adapted from Olive DL, Parker WH, Cooper JM, et al: The AAGL classification system for laparoscopic hysterectomy. Classification Committee of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 7:9–15, 2000.

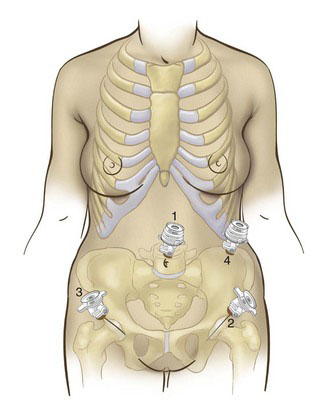

Positioning and placement of trocars

After pneumoperitoneum is obtained, the operating ports should be placed under laparoscopic visualization, at least 8 cm lateral to the midline and about 4 to 5 cm cephalad to the pubic symphysis to avoid injury to the bladder and the inferior epigastric vessels (Fig. 36-1). Selection of a point 2 cm above and 2 cm medial to the anterosuperior iliac spine is another method to place the lateral ports (see Fig. 36-1). If the uterus is large or work outside the pelvis is expected, then the lateral ports may be placed more cephalad.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree