Fig. 15.1

Final 8 Ch pyelostomy placement after ECIRS

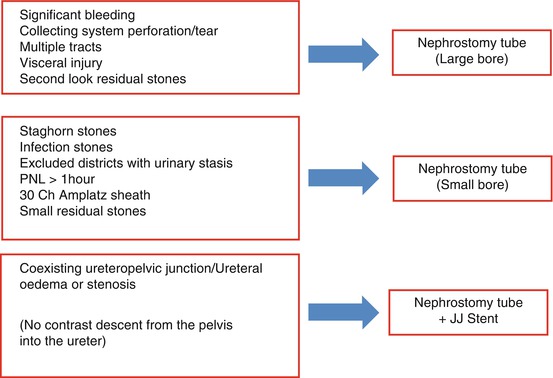

Table 15.1

Criteria suggesting nephrostomy tube application according to our experience in a standard PNL

According to our experience, small-bore nephrostomies are very well tolerated and guarantee an optimal drainage of the treated collecting system per the first postoperative 24–48 h, with minimal analgesic requirements and no increased risk of bleeding (1 % Clavien 2 in our series). Nephrostomy tube can be immediately closed and possibly opened again if the patient suffers from colic pain in absence of a ureteral drainage, which in case of urinary leakage should be applied. Our experience is similar to that reported on a large series of PNL patients (more than 1,000) in the United Kingdom, where the percentage of nephrostomy tube application was 76 % [12].

15.1.2 Tubeless PNL

Recently, the possibility of avoiding nephrostomy tube placement has become real, with the alternative of eliminating it altogether. In fact, the absolute need for postoperative renal drainage after PNL has been definitely questioned and challenged in recent years:

1.

The prolonged tube permanence in the percutaneous tract somehow matures tissues and establishes an anomalous path, leading to prolonged urine leakage (up to about 11 % in the literature) [13].

2.

The supposed compressive hemostatic mechanism on the percutaneous tunnel is lost in case of small-bore nephrostomies, demonstrating that most bleedings are self-limiting [14, 15]. Additionally, the absence of a nephrostomy tube, together with tract closure and conservative measures, might even aid in self-tamponade of the tract, thanks to the thrombolytic effect of urokinase present in the urine [16, 17]. It should also be reported that, going against the tide, the CROES group recently published a paper based on almost 4,000 patients from 96 centers worldwide, concluding that large-bore nephrostomy tubes (≥18F) after PNL seem to reduce bleeding and overall complication rates [18].

15.1.3 Tubeless or Nephrostomy-Free (but Stented) PNL

The description of a conventional PNL without the final application of a nephrostomy tube was first published in 1997 by Bellman and coworkers and has now been accepted as a safe and effective alternative. In both standard [14, 19] and miniaturized PNL [20–22], the tubeless procedure is in any case a stented PNL. In fact, alternative ureteral drainage to prevent urine leakage through the percutaneous tract is provided by the retrograde application of a ureteral catheter or a double-J stent with external string for few days (reducing costs and stent-related morbidity and avoiding endoscopic procedure for its removal) or the placement of a double-J stent for longer periods (one or more weeks, depending upon postoperative stone clearance status, with sometimes significant stent-related symptoms and the need for a postoperative cystoscopy for its removal).

15.1.4 Totally Tubeless (Unstented) PNL

15.1.5 Advantages of Tubeless PNL

Randomized studies, carried out mainly with the patient in prone position [13, 26] and only in a couple of studies in the supine position [27, 28], demonstrated that tubeless procedures imply:

1.

Better patient comfort.

2.

Less pain with reduced postoperative need for analgesics (especially in patients with supracostal access, where the tube irritates the periosteum of the rib).

3.

Quicker recovery and shorter hospital stay in comparison even with small nephrostomy tubes.

4.

Comparable outcomes in terms of stone clearance.

5.

No differences for fever, bleeding complications/blood transfusions, or other complications.

6.

Less urinary leakage.

7.

No chance of a second-look procedure in case of residual fragments.

A tubeless procedure seems feasible with reduced postoperative morbidity even in particular cases, including large stone burdens, children, elderly, obese patients, after previous ipsilateral open surgery, patients with a solitary kidney, horseshoe or ectopic pelvic kidneys, raised serum creatinine levels, on antiplatelet therapy or cirrhotic patients, and bilateral synchronous PNL [19, 29–37].

15.1.6 Inclusion Criteria for Tubeless PNL

Various authors [2, 13, 37] suggested a number of inclusion criteria for tubeless procedures, from which we can argue that one universal solution is not applicable for all patients undergoing PNL and that the optimal renal drainage method should be individualized, depending upon patient features, operative course, procedural complexity, stone burden:

1.

Less than two access tracts.

2.

Stone size less than 3 cm.

3.

No infected stones.

4.

Less than two (one)-hour procedure.

5.

An uncomplicated procedure (no significant intraoperative bleeding, no intrathoracic violation, no significant perforation of the collecting system).

6.

No added procedures (as endopyelotomy or opening of the calyceal diverticulum).

7.

No ureteral/ureteropelvic junction obstruction.

8.

No need for a second-look procedures.

9.

No particular situations (congenital abnormalities, bilateral procedures, children or elderly, ASA score >2, renal failure, etc.).

There is no general consensus about the wisdom of tubeless PNL. Some authors demonstrated equivalent results with early removal of small-bore nephrostomy tubes, anywhere carried out from 1 to 2 days postoperatively and in any case before the patient is discharged home [38, 39].

The European Association of Urology guidelines suggest: in uncomplicated cases tubeless PNL, with or without application of a sealant or double-J stenting (LE 1b, grade of recommendation A); in complicated cases or when a second intervention is necessary a standard PNL with a nephrostomy tube in place.

15.2 Closure of the Percutaneous Tract

Alternative or innovative techniques to establish hemostasis of the tubeless access tract have been reported, from the simple mechanical compression of the percutaneous tract for few minutes at the end of the procedure [7] to the application of deep fascial stitches [40] and from the cryoablation of the tract with a single 10-min freeze-thaw cycle to −20 °C, in which the cryoprobe traverses the nephrostomy tract [38], to its monopolar or bipolar cauterization using a blunt electrocautery loop mounted on a 26F resectoscope [41, 42]. The last frontier is the application of absorbable hemostatic agents (including Surgicel from Ethicon, a blood clot-inducing material made up of oxidized cellulose polymers), with the additional aim to prevent urine leakage [37, 43–45].

Absorbable hemostatic agents include:

1.

Liquid products like fibrin sealants, containing all the components that are necessary to produce a fibrin clot independent of patient-derived factors (Tisseel from Baxter, Evicel from Ethicon, TachoSil from Takeda, thrombin from several companies). Fibrin sealants display both hemostatic and adhesive properties, being the mechanical strength of the fibrin matrix determined by the relative concentration of fibrinogen versus thrombin plus possibly factor XIII and/or an antifibrinolytic agent such as bovine aprotinin or tranexamic acid. Higher thrombin concentrations produce more rapid meshworks, higher fibrinogen concentrations, and stronger but slower meshworks.

2.

Flowable or gelatin matrix products, providing a matrix for platelet adhesion and aggregation, aiding in the formation of a clot when mixed with thrombin and in augmenting the clotting cascade (FloSeal and CoSeal synthetic from Baxter, Surgiflo from Johnson & Johnson, the absorbable gelatin Spongostan). They contain no fibrinogen and allow the thrombin present in the sealant to activate the patient’s natural one. Gelatin materials will additionally swell within the tract from 19 to 400 % greater than the applied volume, adding to hemostasis by means of a compressive effect.

Fibrin glues are expensive and their use raised concerns for a possible lithogenic effect. According to experimental studies in a porcine model, hemostatic gelatin matrix was found to be the most optimal because it remains in fine particulate suspension in urine, whereas fibrin maintains a semisolid gelatinous state and may persist in the tract for up to 30 days, thus inhibiting wound healing [46–50].

15.3 How We Do It: The Authors’ Point of View

Final combined (antegrade and retrograde) flexible evaluation of the stone-free status.

Final endoscopic evaluation of the entity of bleeding from the percutaneous tract.

No bleeding, no residual stone fragments, and no other complicating elements = tubeless PNL feasible (simple mechanical compression of the percutaneous tract).

Final combined endoscopic inspection and antegrade pyeloureterography to evaluate the absence of perforation of the collecting system and the free passage of the contrast medium down the ureter to the bladder through the ureteropelvic junction = totally tubeless (tubeless and stentless) PNL feasible.

In case of modest bleeding with risk of clot formation, small stone fragments not be treated by a second-look procedure, ureteral/ureteropelvic junction edema, ureteral spasm, or stenosis = nephrostomy–free but stented PNL, with a ureteral catheter or a double-J stent with the string left attached, if it has to be removed within few days, and without string if the double-J stent has to be left for 20 days or more.

In case of problematic/complicated PNL = standard procedure, with both nephrostomy and ureteral drainage. The nephrostomy tube can be left closed immediately after PNL, to contribute to tamponade, or opened in case of renal colics, to aid urine drainage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree