Fig. 10.1

CT scan of a 17-year-old boy with near traumatic liver resection. In this case, you may need to complete the liver resection on the initial operation

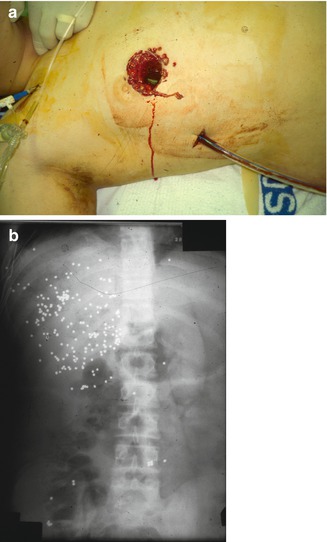

Fig. 10.2

(a) 14-year-old boy with shotgun injury just below the right nipple. On laparotomy, the blast injury nearly resected his liver and had the appearance of currant jelly. (b) Plain film of a 14-year-old boy accidentally shot by his brother at close range while hunting. The entrance wound was at the inferior border of the right nipple. He was transported to the nearest emergency room, where he was given eight units of blood and transported by helicopter to the level I trauma center 50 miles away. The highest blood pressure was 80 mmHg. He was taken immediately to the operating room where a right lobectomy was performed. The wadding from the shotgun shell was found in the middle of the right lobe

A failure of a Pringle maneuver to slow the bleeding likely indicates an injury behind the liver, to the retrohepatic inferior vena cava or a hepatic vein. Be sure to check for a replaced right hepatic artery. Immediately push back and up on the liver, against the spine and diaphragm, to stop the hemorrhage temporarily, followed by prompt perihepatic packing. If hemorrhage is not controlled after a Pringle maneuver and perihepatic packing, there are a few ways to obtain definitive control of the blood supply to the liver—the Heaney maneuver, venovenous bypass, and atriocaval shunting. There have been case reports of interventional radiologists temporarily occluding the inferior vena cava above and below the injury, with catheters, by accessing the femoral vein and internal jugular vein. Rarely, a hepatectomy for trauma has been performed with subsequent transplantation (Fig. 10.2).

Juxtahepatic Venous Injury

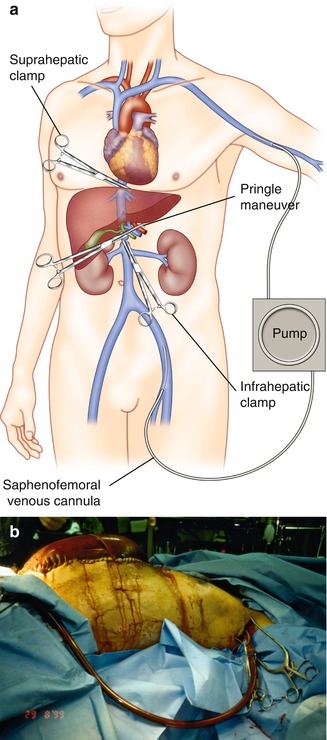

The Heaney maneuver is performed by clamping both the suprahepatic and infrahepatic inferior vena cava while simultaneously applying the Pringle maneuver (Fig. 10.3). During the Heaney maneuver, clamping of the inferior vena cava can lead to cardiac arrest because of the sudden decrease in cardiac preload. It is crucial that central pressures are monitored and that fluid replacement is adequate. The aorta should not be clamped. Doing so will result in worsening acidosis. Once you have control of the inferior vena cava and portal vein, there is less than one hour to repair the injury. Begin by taking down the falciform and right triangular ligament as well as freeing the liver posteriorly from the diaphragm. Occasionally, the right hepatic artery may arise from the superior mesenteric artery (replaced right hepatic). The right hepatic lobe is freed up from the diaphragm and rotated medially away from the diaphragm, exposing the small hepatic veins from segment one communicating directly into the inferior vena cava.

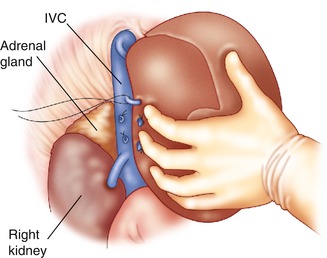

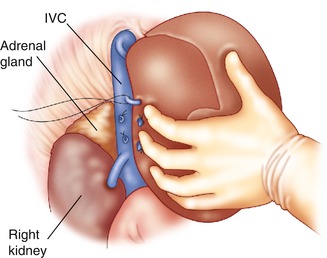

Fig. 10.3

The Heaney maneuver. Vascular isolation of the injured liver by applying vascular clamps to the suprahepatic and infra-hepatic inferior vena cava, in addition to a Pringle maneuver

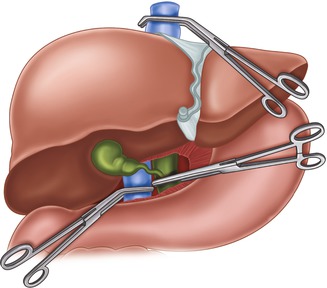

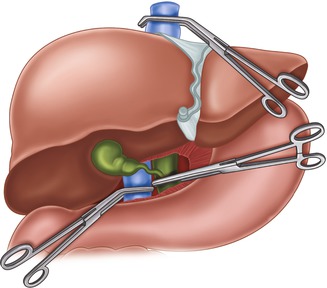

Each of these small veins should be ligated. In extreme deceleration injuries, the small veins are avulsed from the anterior surface of the inferior vena cava creating a linear laceration (Fig. 10.4). If the right hepatic vein is avulsed from the inferior vena cava, place a clamp on the hepatic vein and ligate it (Fig. 10.5). If there is a hole in the inferior vena cava, you can repair this with 4-0 Prolene, taking care to minimize reducing the lumen.

Fig. 10.4

Retrohepatic inferior vena cava

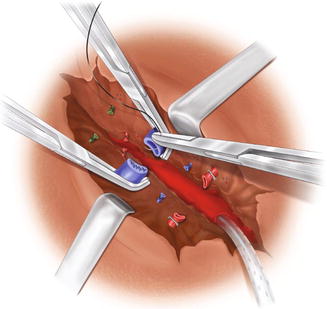

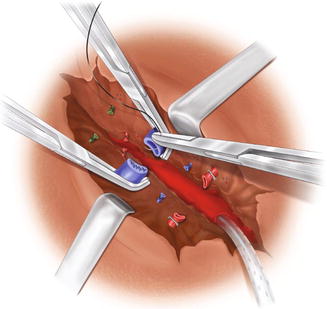

Fig. 10.5

Clamping of right hepatic vein (Reproduced with permission from Ivatury)

An injury to the left hepatic vein should also be considered. The left lobe is mobilized by division of the falciform and coronary ligaments. Medially rotate the left lobe of the liver. You should keep in mind that the left hepatic artery may arise from the left gastric artery (replaced left hepatic). If the left hepatic vein is avulsed from the inferior vena cava, a Satinsky clamp in some injuries can be placed and oversewn. Alternatively, the forefinger can be placed in the hole of the inferior vena cava and a running suture of 5-0 Prolene is advanced as the surgeon’s finger is withdrawn from the laceration. Once the repair is complete, release the clamps from the portal vein and inferior vena cava. If there is control of bleeding, it may be prudent to place a few packs around the repair. The abdomen should be left open with a temporary abdominal closure system such as ABThera™. The patient will be brought to the intensive care for rewarming and resuscitation. This can usually be achieved in three to six hours. The patient is returned to the operating room for another look, pack removal, and closure of the abdomen if possible. Although the Heaney technique involves occlusion of inferior vena cava with no bypass or shunting of blood, it is the preferred method of retrohepatic injury repair. It is the easiest of the three techniques to perform, does not involve additional equipment or teams, and provides the patient with the best chance of survival.

A second method of hepatic vascular isolation is venovenous bypass using a centrifugal pump that was initially described by Starzl (Fig. 10.6). The following explanation is an advanced maneuver and should only be attempted by an experienced liver or trauma surgeon. In addition to having the necessary equipment including the circulating pump, a perfusion team should be immediately available. While the patient is being prepped and draped for surgery, two simultaneous cutdowns are performed. One is over the left saphenofemoral junction and an 18 F Argyle tube is inserted into the saphenous vein, which extends into the inferior vena cava. The other cutdown is performed over the left axillary vein and an 18 F Argyle tube is inserted which extends into the subclavian vein. A vascular clamp is placed across the portal triad to control bleeding from the viscera. The right triangular ligament is taken down (Fig. 10.7). Massive bleeding will be encountered from behind the liver. Venovenous bypass is achieved by attaching the Argyle tubes to the centrifugal pump and circulating blood from the catheter in the saphenous vein through the pump and returning it through the catheter in the axillary vein. Concomitant total hepatic isolation is achieved by clamping or placing Rummel tourniquets around the inferior vena cava just above the renal veins and on the suprahepatic inferior vena cava. In some injuries, it is possible to clamp the suprahepatic inferior vena cava below the diaphragm. Another approach is to perform a sternotomy and clamp or place a Rummel tourniquet above the diaphragm. If the right or left hepatic veins are avulsed from the inferior vena cava, place clamps on the vessels and ligate them. A hole in the inferior vena cava can be repaired with a 4-0 Prolene. Venovenous bypass has the advantage of creating a bloodless field while still returning blood to the heart. This method does not require sternotomy or thoracotomy unless it is necessary to control the inferior vena cava above the diaphragm. Another advantage is the ability of using the circuit to rewarm the patient. The disadvantage is that it is a moderately complex procedure that must happen quickly. While in theory the operation makes sense, the practicality of all the necessary parts coming together makes it difficult. Quick recognition of the retrohepatic injury, a readily available perfusion team and equipment, facile venous cutdown, mobilization of the liver, and placement of catheters are all complex time-consuming tasks that must be done quickly and correctly in order to achieve success with this maneuver (Fig. 10.5).