Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma

Invasion in urothelial carcinoma may arise at the base of a papillary neoplasm (Ta) or within it. It can also be seen as a microinvasive or invasive disease, in association with carcinoma in situ (CIS, or CIS with invasion). Approximately 30% of urothelial carcinomas present with invasive disease and, in some cases, a precursor lesion is not seen, presumably because it has been destroyed by surface ulceration associated with the invasive carcinoma or because the cells have exfoliated into the urine. The morphologic spectrum of invasive urothelial carcinoma is very wide and numerous variants have been described (Chapter 6). Even the usual or conventional type of urothelial carcinoma spans a range of histology.

USUAL OR CONVENTIONAL TYPE OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

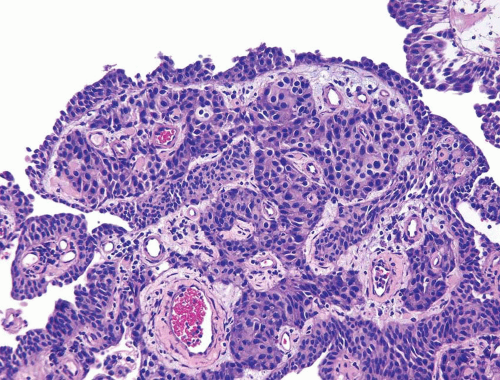

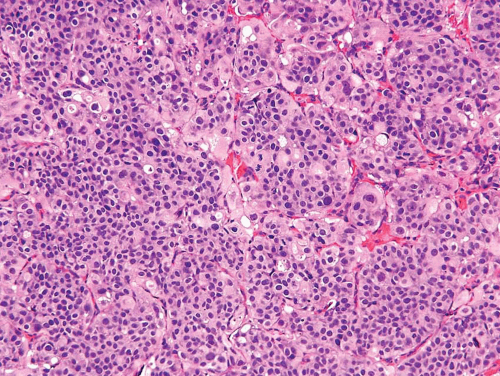

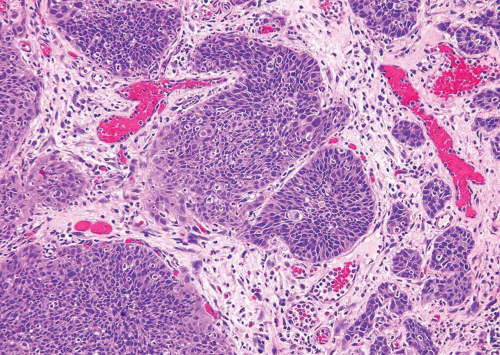

Invasive urothelial carcinoma may present as a polypoid, sessile, ulcerated, or infiltrative lesion in which the neoplastic cells invade the bladder wall as nests, cords, trabeculae, small clusters, or single cells that are often separated by a desmoplastic stroma. The tumor sometimes grows in a more diffuse, sheet-like pattern, but even in these cases, focal nests and clusters are generally present. Occasionally, carcinomas are associated with a pronounced chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, which partially or substantially obscures the underlying tumor cells. In some instances, the inflammation may appear to be an integral component of the neoplasm and mimic the distinctive lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the bladder (Chapter 6). The neoplastic cells in typical or conventional patterns of invasive urothelial carcinoma are usually of moderate size and have modest amounts of pale to densely eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 5.1). Sometimes tumors with a more nest-like architecture, eosinophilic cytoplasm in tumor cells, and prominent stromal vascularity between nests may mimic a paraganglioma (see Chapter 12). In some tumors, the cytoplasm is more abundant and may be clear or strikingly eosinophilic. The presence of clear cells, with rare exceptions, is focal and should not lead to the diagnosis of clear cell adenocarcinoma, which has a very typical histology. Invasive tumors are mostly high grade, although there is a spectrum of some cases exhibiting marked anaplasia; focal tumor giant cell formation may be seen. Only a small minority of invasive urothelial carcinomas has a low-grade histology

(see Chapter 6 for a description of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma); however, in these cases the outcome is not determined by tumor grade but rather by stage. According to the World Health Organization 2004/International Society of Urological Pathologists [WHO (2004)/ISUP] classification, invasive tumors are graded as low and high. Features indicative of the urothelial character of cells of urothelial carcinoma include the presence of longitudinal nuclear grooves that are often appreciable in low-grade tumors, but are rarely seen in high-grade tumors.

(see Chapter 6 for a description of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma); however, in these cases the outcome is not determined by tumor grade but rather by stage. According to the World Health Organization 2004/International Society of Urological Pathologists [WHO (2004)/ISUP] classification, invasive tumors are graded as low and high. Features indicative of the urothelial character of cells of urothelial carcinoma include the presence of longitudinal nuclear grooves that are often appreciable in low-grade tumors, but are rarely seen in high-grade tumors.

FIGURE 5.1 Irregular nests of urothelial carcinoma with cells having moderate amounts of cytoplasm and pleomorphism. |

Approximately 10% of urothelial carcinomas contain foci of glandular and approximately 60% show variable amounts of squamous differentiation (see Chapters 8 and 9). This may not reflect the actual frequency as this information is not consistently or accurately recorded by pathologists. Glandular differentiation is usually in the form of small tubular or gland-like spaces in conventional urothelial carcinoma (urothelial carcinoma with gland-like lumina), or as a histology similar to enteric adenocarcinoma (1, 2, 3). Rarely, a coexistent signet ring cell or mucinous component may be present. To designate squamous differentiation, one must see clear-cut evidence of squamous production (intracellular keratin, intercellular bridges, or keratin pearls), and the degree of squamous differentiation, when present, usually parallels the grade of the urothelial carcinoma. In general, urothelial carcinomas have a relatively nondescript morphology, which when viewed in isolation cannot be differentiated from poorly differentiated carcinomas of other types. Therefore, the presence of squamous or glandular differentiation in a poorly differentiated neoplasm, particularly at metastatic sites and in the context of a bladder primary, should suggest the possibility of urothelial differentiation. To designate a bladder tumor as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma, a pure or almost pure histology of squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma is required. The presence of squamous

and glandular differentiation in urothelial carcinomas has generally been thought of as lacking any clinical significance. In stage-matched cases, the outcome of typical urothelial carcinoma is similar to those with aberrant differentiation (4). However, some studies have suggested that these variants may be more resistant to chemotherapy or radiation therapy than pure urothelial carcinoma, but this has not been confirmed (5, 6). From a practical viewpoint, we do make note of prominent squamous or glandular differentiation in urothelial carcinoma by using diagnostic terminology such as “invasive urothelial carcinoma with prominent squamous (40%) and glandular (25%) differentiation.” In cases of metastatic tumor, knowledge of the presence and percentage of divergent differentiation may be useful to facilitate comparison with the primary.

and glandular differentiation in urothelial carcinomas has generally been thought of as lacking any clinical significance. In stage-matched cases, the outcome of typical urothelial carcinoma is similar to those with aberrant differentiation (4). However, some studies have suggested that these variants may be more resistant to chemotherapy or radiation therapy than pure urothelial carcinoma, but this has not been confirmed (5, 6). From a practical viewpoint, we do make note of prominent squamous or glandular differentiation in urothelial carcinoma by using diagnostic terminology such as “invasive urothelial carcinoma with prominent squamous (40%) and glandular (25%) differentiation.” In cases of metastatic tumor, knowledge of the presence and percentage of divergent differentiation may be useful to facilitate comparison with the primary.

A subset of invasive urothelial carcinomas may exhibit vascular invasion. This parameter should be diagnosed with care because invasive urothelial carcinomas, particularly those with limited or early invasion, frequently show retraction artifact, which mimics vascular-lymphatic invasion. In two studies, only 14% and 40% of cases originally diagnosed with vascular invasion on the basis of morphology could be proven by immunohistochemistry (7, 8). Criteria for recognition of vascular invasion are outlined later in this chapter and its prognostic significance, especially in node negative carcinomas, is uncertain (9).

In addition to the morphology described earlier, invasive urothelial carcinoma has a propensity for myriad other patterns of divergent differentiation (e.g., small cell carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma) or variation in histology (micropapillary, microcystic, and nested) in approximately 10% of cases. These are described in detail in Chapter 6.

STAGING OF BLADDER CANCER

Staging is the most powerful prognostic indicator in urothelial carcinoma and is a major defining parameter in the management of this disease (4). The TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) staging system defines T1 tumors as those invading the lamina propria but not the muscularis propria (10). Even though several studies have shown that T1 tumors bear a less favorable prognosis than Ta (noninvasive) neoplasms (11, 12, 13), clinically Ta and T1 tumors are usually lumped together by urologists under the term superficial bladder tumors, partially because these two stages traditionally have been managed conservatively. Another possible factor contributing to the clinician’s rationale in grouping Ta and T1 tumors as superficial is the pathologists’ inability to always accurately recognize lamina propria invasion (14, 15). We discourage the use of the term superficial to describe T1 tumors since contemporary series in which great care was taken to classify Ta and T1 correctly have shown clear differences in progression rates (16, 17). Tumors with involvement of the muscularis propria and beyond (pT2-4, or invasive tumors) are usually managed with definitive surgical therapy (i.e., cystectomy) or radiation therapy with or without

adjuvant therapy. Approximately 10% of bladder carcinomas, treated by cystectomy, have no evidence of residual disease (pT0). Three to seven percent of patients treated by cystectomy will have lymph node metastases and the clinical outcome varies considerably. Patients with CIS and lymphovascular invasion, at primary transurethral resection, tend to have a more adverse outcome (18).

adjuvant therapy. Approximately 10% of bladder carcinomas, treated by cystectomy, have no evidence of residual disease (pT0). Three to seven percent of patients treated by cystectomy will have lymph node metastases and the clinical outcome varies considerably. Patients with CIS and lymphovascular invasion, at primary transurethral resection, tend to have a more adverse outcome (18).

Before discussing lamina propria (T1) and muscularis propria (T2 and T2+) invasion, it is important to be aware of the type of specimens encountered in bladder pathology and some histologic aspects of the bladder wall that are pertinent for the discussion of invasion.

Most small bladder tumors (usually less than 1 cm in size) can frequently be excised by cold cup biopsies. This procedure yields specimens in which the cellular architecture is mostly preserved and orientation is easier to maintain after embedding. The resulting hematoxylin and eosin sections show the urothelial neoplasm, the lamina propria, and often superficial muscularis propria with orientation maintained, thus facilitating assessment of invasion (19). Larger tumors (usually greater than 1 cm) usually require hot loop resection (transurethral resection of bladder tumor, or TURBT), in which the urologist attempts to include a generous sample of the underlying muscularis propria to enable adequate pathologic staging. The specimens rendered by this procedure are often fragmented, heavily cauterized, and difficult to orient. Sections from these specimens are complicated by thermal artifact, tangential sectioning, and disruption of the tumor and normal architecture. Changes related to prior TUR may also add to the difficulty. While examining both types of specimens, it is important to note the presence or absence of muscularis propria in the specimen to assess its involvement by neoplasia and to provide feedback to the urologist regarding the adequacy of resection.

The subepithelial connective tissue is a compact layer of fibrovascular connective tissue. Smooth muscle actin staining has revealed a continuous band of ill-defined, haphazardly oriented, compact spindle cells that are immediately subjacent to the urothelium in all cases. This layer has been referred to as suburothelial band of myofibroblasts. Beneath this layer, in most instances, the submucosa is further divided by a thin layer of smooth muscle fibers (muscularis mucosae) into a lamina propria proper, which is superficial, and a submucosal layer, located between the muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria. These anatomic landmarks may be entirely replaced by dense connective tissue at the sites of prior biopsy. It was not until the 1980s that the muscularis mucosae layer of the urinary bladder was described (20, 21, 22), alerting pathologists and urologists of the importance of recognizing and differentiating it from the underlying compact smooth muscle bundles of muscularis propria. Muscularis mucosae fibers are usually thin, often discontinuous, wispy and wavy fascicles of smooth muscle, which are frequently associated with large-caliber blood vessels, and surrounded by loose fibroconnective tissues. Most studies have identified some degree of this layer in 94% to 100% of cystectomy specimens

(21, 22) and in approximately 18% to 83% of specimens from biopsies or TURBT (16, 23). Topographical variations in caliber of muscularis mucosae muscle exist between different regions of the bladder (24), and the lamina propria vascular plexus may not be consistently associated with muscularis mucosae muscle. Muscularis mucosae muscle bundles may be thicker (hypertrophic form) or rarely assume the caliber of muscularis propria muscle bundles. Distinction is possible by location in the lamina propria, and being distinct from deeper muscularis propria muscle (24). Muscularis propria fascicles, on the other hand, are usually thick and compact, divided into distinct bundles surrounded by perimysium. Occasionally, muscularis mucosae bundles undergo hypertrophy especially after biopsy or at the base of the tumor, and in such situations the distinction between muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria, especially in biopsy or TURBT specimens, may be difficult. The deep (outer half) muscularis propria often rest on the perivesical fat. The boundary between them is not abrupt. Fat is present in all layers of the bladder beneath the urothelium; the frequency and amount increase from the superficial lamina propria to the deep lamina propria, and to the muscularis propria (25).

(21, 22) and in approximately 18% to 83% of specimens from biopsies or TURBT (16, 23). Topographical variations in caliber of muscularis mucosae muscle exist between different regions of the bladder (24), and the lamina propria vascular plexus may not be consistently associated with muscularis mucosae muscle. Muscularis mucosae muscle bundles may be thicker (hypertrophic form) or rarely assume the caliber of muscularis propria muscle bundles. Distinction is possible by location in the lamina propria, and being distinct from deeper muscularis propria muscle (24). Muscularis propria fascicles, on the other hand, are usually thick and compact, divided into distinct bundles surrounded by perimysium. Occasionally, muscularis mucosae bundles undergo hypertrophy especially after biopsy or at the base of the tumor, and in such situations the distinction between muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria, especially in biopsy or TURBT specimens, may be difficult. The deep (outer half) muscularis propria often rest on the perivesical fat. The boundary between them is not abrupt. Fat is present in all layers of the bladder beneath the urothelium; the frequency and amount increase from the superficial lamina propria to the deep lamina propria, and to the muscularis propria (25).

DIAGNOSIS OF LAMINA PROPRIA INVASION

Recognition of lamina propria invasion by urothelial carcinoma is occasionally one of the most challenging diagnoses in surgical pathology, and problems with interobserver reproducibility have been documented (18, 26) (efigs 5.1-5.32). Often faced with distorted, cauterized, and tangentially sectioned specimens, the pathologist should follow strict criteria to diagnose lamina propria invasion (Table 5.1). While evaluating tumors for invasion, it is important to focus on the features discussed in the following paragraphs.

Histologic Grade of Tumor

Lamina propria invasion should be carefully sought in all high-grade papillary carcinomas. Although invasion is not a common finding in low-grade tumors, it is much more common in high-grade lesions. In our experience, more than 90% of pT1 tumors are high grade. Thus, even though clear-cut histologic signs of invasion are required for the diagnosis of invasion into lamina propria, regardless of grade, the level of suspicion should be higher in those cases with a high histologic grade.

Characteristics of Invading Epithelium

The invasive front of the neoplasm may show one of the several features: single cells or irregularly shaped nests of tumor within the stroma, architectural complexity not conforming to the usual regularity of papillary neoplasms, or an irregular, disrupted, or absent basement membrane (Figs. 5.2, 5.3). Sometimes, tentacular or finger-like extensions can be seen arising from the base of the papillary tumor. Frequently, the invading nests appear morphologically different from the cells at the base of the noninvasive component of the tumor, with more abundant cytoplasm and often with a higher degree of pleomorphism (Figs. 5.4, 5.5 and 5.6). This phenomenon has been called paradoxical differentiation when seen at other sites such as the uterine cervix.

TABLE 5.1 Criteria for Diagnosis of Invasion into Lamina Propria by Urothelial Carcinoma | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stromal Response

The lamina propria may react to invasion in one or more of the following forms:

1. Desmoplastic or sclerotic stroma: The stroma may be cellular with spindled fibroblasts and variable collagenization, with or without inflammation.

2. Retraction artifact: In some cases, retraction artifact that mimics vascular invasion is seen in tumors invading only superficially into the lamina propria (Figs. 5.7, 5.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree