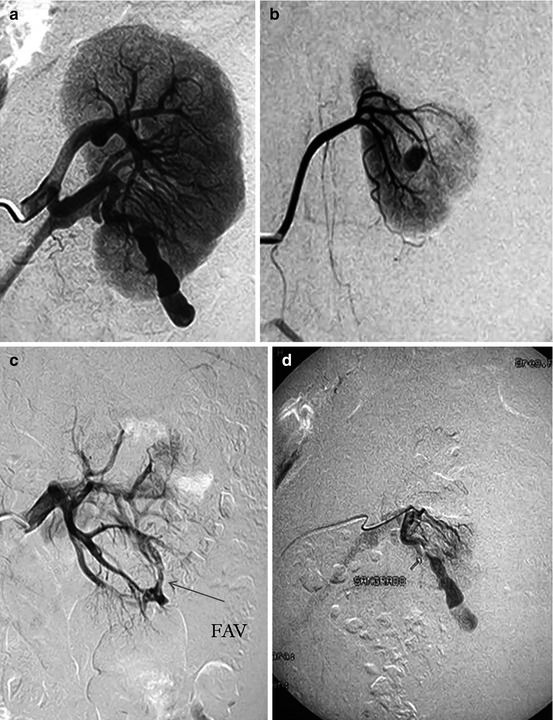

Fig. 20.1

(a) Intraperitoneal bowel perforation (b) Intraperitoneal bowel lesion, surgical repair

20.3.2 Pleural Lesions

Any intercostal puncture passes through the diaphragm and increases the risk of pneumothorax, hydrothorax and/or haemothorax. The incidence of liquid accumulating in the pleura varies between 3 and 38 % when the puncture is performed above the 11th rib [28, 29]. The lung and pleura can be damaged when the decision is made to reach the kidney by a puncture above the 11th rib [30]. Hopper states that these cases reach 86 % in the right pleura and 29 % in the right lung and on the side 79 % in the left pleura and 14 % in the left lung.

These lesions often clear up by themselves spontaneously. Only in cases of extensive pneumothorax or haemopneumothorax is it necessary to place underwater seal thoracic drainage. Open surgery is seldom required.

20.3.3 Hepatic Lesions

Hepatic lesions are unusual (Fig. 20.2). They are found to be associated with hepatomegaly or right punctures above the eleventh rib. They do not often require an active resolution.

Fig. 20.2

CT scan demonstrating the transhepatic passage of the nephrostomy tube (Courtesy of A. Hoznek)

20.3.4 Splenic Lesions

Splenic lesions are also unusual. They are associated with splenomegaly or left punctures above the 11th rib. They often bleed in an unconstrained manner and may require splenectomy. Although a recent paper has shown the possibility of a conservative form of treatment, this seems to be only an exceptional option [31].

20.3.5 Other Visceral Injuries

Other unusual lesions which have been described, such as biliary, duodenal and intestinal mesenteric ones, are generally caused by the perforation of the renal pelvis by exaggerated progression of a dilator or needle.

20.3.6 Vascular Lesions

The second objective of the needle, as well as avoiding a lesion of a neighbouring organ, is to reach the urinary tract passing through the renal parenchyma without causing arterial bleeding. In order to reduce this risk to the upmost, it is necessary to know the arrangement of the renal artery and its branches in relation to the pelvis and the calyces. The vascularisation of the kidney is detailed in Chap. 6.

The safest area for the puncture is normally the dorsal calyx of the lower pole. It is especially important to bear in mind the pathway of the infundibular arteries, and thus the safest way to access the urinary system percutaneously is frontally through the papilla of a calyx, following the axis of the infundibulum [32–34]. A vascular lesion may occur as the consequence of an intrarenal puncture through the infundibulum. In fact, the puncture of the kidney through the infundibulum of an upper pole calyx is very dangerous, as this zone is completely surrounded by large blood vessels, both venous and arterial. In the casts, when the puncture was via the neck, 67 % of the cases presented vascular lesion, of which 26 % presented arterial lesion. When the puncture is through a mid-renal infundibulum, 23 % of the cases present lesion to blood vessels. When the puncture is through a lower pole infundibulum, 13 % of cases present a vascular lesion.

These findings clearly show that the puncture through the infundibulum is not a safe access, since there is a high risk of lesion to an arterial blood vessel [35]. On the other hand, access through the papilla showed venous lesion in 8 % of the cases (regardless to the selected calyx) and no arterial lesions.

Additionally, following the same criterion of intending to avoid lesions to infundibular blood vessels that run parallel to the calyceal necks, not only should the tip of the papilla be punctured but the needle should also follow the direction of the axis of the calyceal neck (a further condition for an ideal puncture). This way, the needle, once inside the calyx, has a long endoluminal pathway towards the pelvis, decreasing the risk of coming out and causing arterial lesions.

Unfortunately, the projection of a straight line that follows the axis of the inferior calyx and passes through the centre of the papilla generally enters the skin at a point outside the safe area for lumbar puncture. This means that an ideal puncture is very rarely feasible. Therefore, the precaution should always be taken of advancing the needle just a few millimetres, once the papilla is punctured, and removing its mandrel by introducing a guide wire towards the renal pelvis in order to maintain the way.

20.4 Dilation-Related Complications

Once the guide wire is inserted, the access tract is dilated. Throughout this step, the main concern is to avoid an exaggerated progression of the dilators inside the urinary tract. It is also opportune to remember that the punctured calyx tends to be occupied by stones, and untimely dilation can cause damage to the mucosa. These complications during the dilation are avoided by making precise, gentle and controlled movements.

A current controversy is what calibre to use in order to dilate. It is accepted that the greater the calibre of the Amplatz sheath inserted, the greater the risk of lacerations on the one hand but, on the other hand, the shorter the operating time (as it enables the extraction of larger-sized fragments) and a guarantee of lower intrarenal pressures, decreasing the risk of sepsis.

The dilation usually makes any mistake made during the puncture evident. Thus, a peripheral papillary puncture can lead to bleeding due to parenchymal laceration during the dilation.

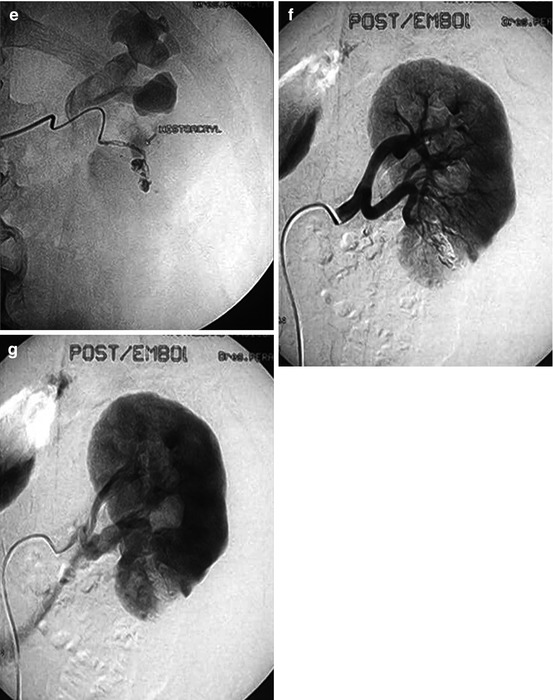

When bleeding is present, it must be determined whether it is venous or arterial (Fig. 20.3a–c). Venous bleeding is easy to solve. A simple occlusion of the venous flow for a few minutes triggers the quick clot formation and allows the procedure to continue without major frights. However, arterial bleeding, fortunately far less common, is a urological emergency which requires an immediate solution by means of a superselective embolisation (Fig. 20.3d–g).

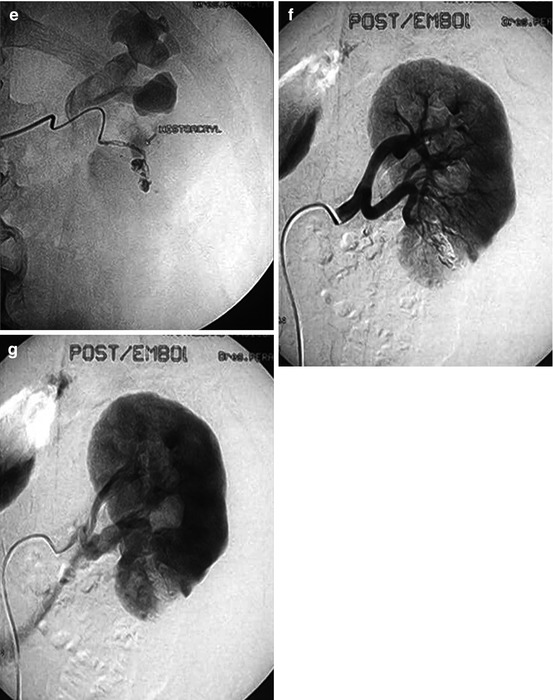

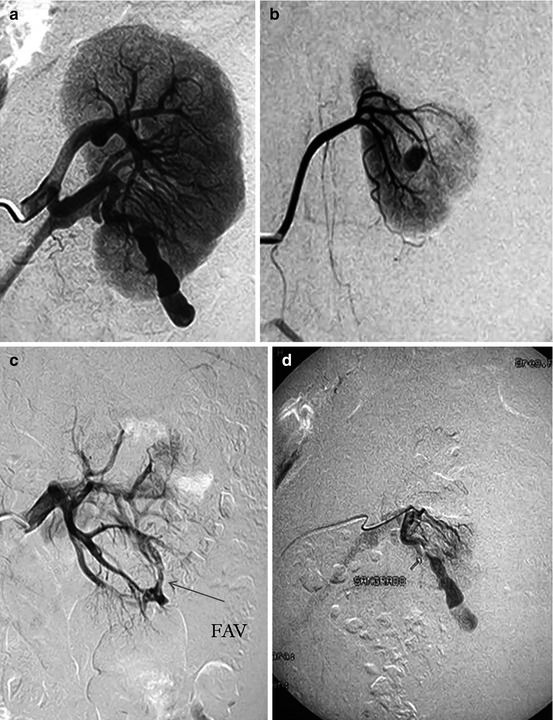

Fig. 20.3

(a) Arteriographic evidence of renal active bleeding (b) Arteriographic evidence of a pseudoaneurysm (c) Arteriographic evidence of an arrow: arteriovenous fistula (d) Selective arteriographic catheterisation of the vascular lesion (e) Superselective embolisation of the vascular lesion (f) Postembolisation control: arterial phase (g) Postembolisation control: nephrographic phase: ischemic area

20.5 Manipulation-Related Complications

Although there are various potential complications at this stage, all of them can be easily prevented or limited. The first is the loss of the nephrostomy tract due to the slipping out of the Amplatz sheath. This is prevented by means of a previous safety guide wire insertion, especially the “through and through” (kebab) guide wire. In case the access tract is lost, it may be quickly regained with a safety guide wire in place. The nephroscope follows the guide wire and the sheath is reinserted.

With no safety guide wire in place, the same situation becomes more complex. It may be of help to retrogradely inject contrast medium mixed with indigo carmine or a little air into the ureteral catheter; the dye or the bubbles will come out through the fistulous tract, observed by the nephroscope and under radioscopic control. During these manoeuvres, it is important to use the smallest amount of fluids possible, for the shortest length of time possible (especially if it is not saline), to avoid an absorption syndrome [36–38]. The absorption syndrome is a rarity when the sheath is adequately placed within the urinary tract but proves to be a potentially severe complication when the fluids are dispersed in the retroperitoneum, requiring clinical and nephrological management and high complexity support and control.

If the attempt of regaining the lost access tract is not successful, an alternative correct decision could be to create a new access tract re-puncturing the patient or to suspend the procedure (possibly inserting a double-J stent) programming a further surgery later on.

20.6 Fragmentation-Related Complications

Usually, complex calculi need to be fragmented in order to make their extraction possible via the Amplatz sheath. Any available energy can be used, whether ultrasonic, pneumatic, electrohydraulic or laser. Each one has different physical features as well as potential harmful mechanisms causing lesion to the surrounding mucosa. For instance, the obstruction of the probe of the sonotrode during ultrasonic lithotripsy can cause thermal lesions. The expansive features of the explosive evaporation of the liquid around the electrohydraulic fibre can cause mucosal laceration. The movement of the probe being propelled by pneumatic or electromagnetic pulses, following the principles of ballistics, can cause mechanical perforation of the renal cavities. The hyperthermia of the tip of the laser fibre, if inadequately controlled, can cut through tissues as if they were butter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree