Our understanding of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/BPS) has evolved with the advancements in our understanding of visceral pain syndromes. The concept of IC/BPS as a visceral pain disorder is used as a model to base a targeted approach to the management of patients with IC/BPS. Guidelines for the treatment of both the bladder and nonbladder pain disorders are reviewed.

- •

IC/BPS is a visceral pain syndrome and therefore central sensitization is key to symptom evolution and typically involves bladder as well as non-bladder pain generators.

- •

IC/BPS management involves identification of all pain generators and treatment of all pain generators.

- •

Success of therapy is related to duration of symptoms and number of pain disorders and therefore early identification and treatment of this visceral pain disorder is paramount.

- •

Multi-modal therapy and patient education is the key to successful management of IC/BPS.

Over the past 10 years, we have learned much about the pathophysiology of IC/BPS. The treatment of this disorder would be much more successful if we understood the cause of the pain disorder. Although it is likely a heterogeneous disorder with multiple triggers, it is generally agreed that it likely involves some degree of urothelial dysfunction and neuropathic upregulation that includes the process of central sensitization. Recent work also points to the multiple comorbidities (ie, nonbladder pain syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome [IBS], vulvodynia, and voiding dysfunction) that contribute to and may potentiate the bladder symptoms.

The goal of treatment of any pain disorder is to first improve the quality of life of our patients. This goal can best be realized if we, as clinicians, identify each component of our patients’ pain experience (pain generators) and treat each of these contributing factors. These comorbidities not only add to our patients’ suffering but if not treated, then these other pain generators will continue to produce noxious stimuli that are involved in the maintenance of the central sensitization that is key to the persistence of bladder symptoms.

So with this review, the author briefly describes the neuropathology of IC/BPS and explains why patients often develop these nonbladder pain disorders and, therefore, why these are also important to identify and treat. The author then offers a targeted approach to patients with IC/BPS that involves the management of the bladder pain disorder and the management of the other pain generators. This approach has the potential to downregulate the central sensitization that is at the heart of any visceral pain disorder.

Conceptualization of IC/BPS

As noted in the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines for the management of IC, it is not known whether IC/BPS is a primary bladder disorder or if the bladder symptoms are secondary to phenomena resulting from another cause. This statement is supported by a large body of evidence concerning visceral pain syndromes. Although IC/BPS is typically described as a disease of the urothelium and there is abundant evidence as to the abnormalities located at this peripheral site, pathologic conditions can occur elsewhere with these urothelial changes developing as a secondary abnormality. In addition to the peripheral abnormalities involving the urothelium, afferent nerve activity, and mast cells, visceral pain disorders can lead to changes within the spinal cord (central sensitization) that can maintain pain long after the removal of the peripheral insult. The changes of central sensitization can be demonstrated in our patients with IC/BPS (startle reflex and diffuse allodynia) and have been described in detail by many investigators. Central sensitization results in the development of multiple neuropathic abnormalities that are thought to trigger the multiple secondary pain disorders and dysfunctions that are so common in patients with IC/BPS. One example of this is the well-understood process of viscero-visceral crosstalk that results in symptoms in neighboring organs in patients with IC/BPS. Classic examples are the development of IBS or increasing dysmenorrhea. This upregulation of the spinal cord (often referred to as wind up) is a major contributor to the development of the nonbladder pain syndromes so common in patients with IC/BPS. Other common nonbladder pain disorders in our patients with IC/BPS include vulvodynia and pelvic floor hypertonic dysfunction (with its associated voiding dysfunction). We now understand that a plausible explanation for the development of these abnormalities includes the process of viscerosomatic and viscera-muscular–induced hyperalgesia and dysfunction. Both are manifestations of central sensitization.

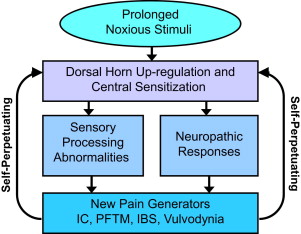

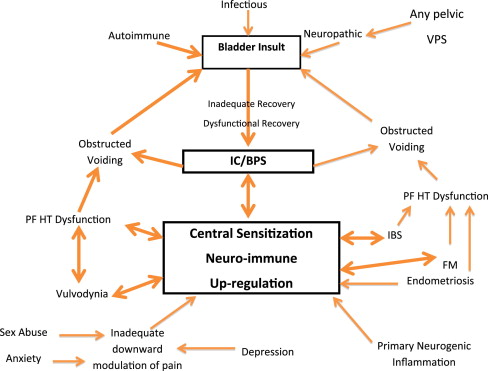

The key concept to grasp while reviewing the management of IC/BPS is that many of these comorbid pain disorders produce additional noxious input to the sacral cord. This input furthers the upregulation of the dorsal horn and maintenance of the sensitization that results in the perpetuation of chronic pain ( Fig. 1 ). Even if the original insult is removed, the persistence of the sensory processing abnormalities and these neuropathic reflexes result in persistent pain. For this reason, multimodal therapy is so important in the treatment of patients with visceral pain disorders, such as IC/BPS and IBS. Therapy directed toward the peripheral pain generator and systemic or centrally directed therapy should provide the highest potential for improved patient quality of life. The clinician ideally uses a careful history and questionnaires to identify the primary pain generator and secondary pain generators ( Fig. 2 ) so that therapy directed toward all pain generators will attempt to downregulate the process of central sensitization by decreasing the volume of noxious stimuli impacting the patients’ spinal cord. The importance of early identification of patients with visceral pain syndromes and aggressive therapy is exemplified by the finding that the likelihood of successful therapy is directly related to the duration of symptoms and the number of associated pain disorders. Multiple studies have shown the benefit of multimodal therapy for chronic pain and recent studies support this concept specifically in patients with IC/BPS. This concept of multimodal therapy is noted as a first-line therapeutic approach in the AUA guidelines for the treatment of IC.

Targeted management of IC/BPS

General Patient Care

Patient education is an extremely important early step in patient care. Often patients have been told they have suffered from repeated bladder infections, yeast infections, and overactive bladder. They have been given antibiotics and anticholinergics in an attempt to decrease their bladder symptoms. Teaching patients about IC/BPS as a chronic pain disorder that can be controlled and even placed into remission with therapy is extremely important. Patients must understand that their participation in the management of their symptoms is an important component of successful therapy. The identification of symptom triggers, such as diet, stress, insomnia, depression, and hormone fluctuations, allows patients and clinicians to work together to initiate therapy. Our discussions with patients also emphasize the importance of managing not only the comorbid pain disorders but also the environmental triggers and potentiators to their pain. This discussion initiates a process of patient empowerment, so they can become involved in what needs to be done to get better. Patients typically have already come to understand that these other pain disorders are somehow linked to their bladder symptoms, so when they learn the importance of managing these other pain disorders, they are typically in full agreement Table 1 .

| History | Findings | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulvodynia | Vulvar/introital pain |

|

|

| IBS | Bowel distention with temporally associated pain |

|

|

| PF hypertonic dysfunction |

|

|

|

Targeted management of IC/BPS

General Patient Care

Patient education is an extremely important early step in patient care. Often patients have been told they have suffered from repeated bladder infections, yeast infections, and overactive bladder. They have been given antibiotics and anticholinergics in an attempt to decrease their bladder symptoms. Teaching patients about IC/BPS as a chronic pain disorder that can be controlled and even placed into remission with therapy is extremely important. Patients must understand that their participation in the management of their symptoms is an important component of successful therapy. The identification of symptom triggers, such as diet, stress, insomnia, depression, and hormone fluctuations, allows patients and clinicians to work together to initiate therapy. Our discussions with patients also emphasize the importance of managing not only the comorbid pain disorders but also the environmental triggers and potentiators to their pain. This discussion initiates a process of patient empowerment, so they can become involved in what needs to be done to get better. Patients typically have already come to understand that these other pain disorders are somehow linked to their bladder symptoms, so when they learn the importance of managing these other pain disorders, they are typically in full agreement Table 1 .

| History | Findings | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulvodynia | Vulvar/introital pain |

|

|

| IBS | Bowel distention with temporally associated pain |

|

|

| PF hypertonic dysfunction |

|

|

|

Bladder-targeted therapies

Behavior Modification

First-line therapy typically involves behavior modification, which includes fluid management (48–64 oz/d) with the avoidance of bladder irritants, such as acidic foods, alcoholic beverages, caffeine, and so forth. Data are limited concerning the benefits of dietary manipulations on our patients’ symptoms but especially in those who report dietary triggers education about the importance of avoidance is important. The use of over-the-counter supplements is poorly studied but calcium glycerophosphate (Prelief) does seem to benefit patients with neutralization of acidic foods for both bladder and bowel symptoms.

Oral therapies

Pentosan Polysulfate

Pentosan polysulfate (PPS) (Elmiron) is the only oral medication that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved for the management of IC. PPS is the most studied oral medication for IC, with more than 500 patients from 7 randomized trials. These trials are nicely summarized in the AUA guidelines with grade B level evidence concerning efficacy (level of evidence stated are as per the AUA guidelines reference). Results concerning the benefit have been contradictory, but evidence would support 300 mg/d, with the duration of therapy likely a key component to the demonstration of response. The onset of the response seems to be directly associated with the duration of symptoms. Failure to respond after 6 months of therapy is generally thought to be an adequate trial. The mode of action seems to be the replenishment of the glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer defects and the benefit from the potential antihistaminic effects of this medication on mast cells, which are generally thought to play a role in IC. Adverse event rates are low, with a rate that generally is similar to the placebo groups studied (evidence level B).

Amitriptyline

Amitriptyline (Elavil) is a commonly used medication for various pain disorders. One randomized controlled trial reported efficacy in patients with IC in 63% of patients showing significant improvement in symptoms. Dosage titration is key to the balance of efficacy with drug-induced side effects. The typical starting dose is 12.5 mg at bedtime and increasing the dose as tolerated to 25 to 75 mg. The mode of action is multifactorial, including anticholinergic affects, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, and sedation-induced improvement of sleep disorders. However, this sedation is the most common side effect that makes this drug difficult to tolerate for some patients (evidence level B).

Hydroxyzine

Hydroxyzine (Vistaril) is a commonly used drug for patients with IC, especially if they do not tolerate amitriptyline or if they have a significant history of allergies. Two studies (1 randomized controlled and 1 observational) demonstrate a benefit in patients with minimal side effects other than sedation. The observational study done in patients with significant history of allergies had a 55% response rate. This drug, therefore, is used at bedtime, typically at the dosage of 50 mg each night. Hydroxyzine is an antihistamine with antianxiety and analgesic properties (evidence level C).

Cyclosporine A

This immunosuppressive agent that is used to prevent organ rejection in organ transplant recipients has been used in a selective group of patients with ulcerative and nonulcerative IC unresponsive to traditional therapies. In a randomized trial, compared with PPS, it was found to have a 75% response rate with a decrease in frequency and pain. A response is seen within 6 weeks. Observational studies that involve therapy for up to 5 years demonstrate sustained benefit, with a rapid return of symptoms typically occurring with cessation of therapy. The initial dose is 3 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses. A slight reduction in dosage (reduced to 1.5 mg/kg after initial response), however, is often nicely tolerated. However, side effects can be serious, and close monitoring of blood pressure and serum creatinine is required during the first few weeks of therapy and every 6 months after that. More commonly seen adverse events of gingival hyperplasia and induction of facial hair growth can be bothersome, especially at higher doses. The long-term safety of this immunosuppressive agent has not been studied in patients with IC and its use is certainly off-label, but in clinical practice with patients who suffer from persistent symptoms, it has provided impressive clinical results. The mode of action involves the modification of the neuroimmune response to inhibit maintenance of inflammation (evidence level C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree