■

Collagenous colitis

Clinical features

Patients with collagenous colitis (CC) present with a history of chronic watery diarrhea. Colonoscopy typically shows normal or near normal mucosa, although there are a few reports of linear mucosal tears that were thought to occur upon insufflation during endoscopy. This has been referred to as “cat scratch colon” because of the endoscopic appearance. In addition, there are rare reports of CC with pseudomembranes. Affected females largely outnumber males, and most patients are middle-aged or older.

It appears as though a luminal antigen or antigens are important in the pathogenesis of CC. Diversion of the fecal stream causes the histologic changes of CC to regress, while reestablishing the fecal stream induces a relapse. Studies have shown a strong association of CC with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and with celiac disease. Other medications have also been associated with CC, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), proton pump inhibitors, simvastatin, and lisinopril.

Definition

- ■

Chronic nondistorting colitis with characteristic subepithelial collagen deposition and surface epithelial damage

Incidence and location

- ■

1 to 2.3 per 100,000 population

- ■

Generally involves the entire colon, but relative rectal or left-sided sparing can be seen

- ■

Subepithelial collagen may be patchy

Gender, race, and age distribution

- ■

Female predominance (males to females, 1:8)

- ■

Primarily affects middle-aged to older adults

- ■

Mean age, 59 years

Clinical features

- ■

Chronic watery diarrhea with normal or near normal endoscopy

Prognosis and therapy

- ■

Most patients respond to symptomatic or anti-inflammatory therapy.

Pathologic features

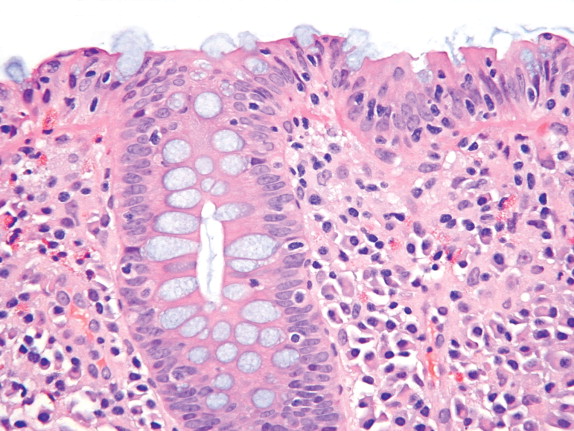

At low power, biopsy specimens of CC often show a pink subepithelial “stripe” with an intact crypt architecture and an increase in superficial lamina propria mononuclear cells ( Fig. 11-1 ). At higher magnification the lamina propria shows increased plasma cells and eosinophils, and the surface epithelium has a patchy infiltrate of intraepithelial lymphocytes with areas of surface damage ( Fig. 11-2 ). The surface epithelium may also be stripped off of the thickened collagen table, making it harder to make the diagnosis. The subepithelial collagen usually blends imperceptibly with the basement membrane to form a hypocellular pink band that often entraps small capillaries ( Fig. 11-3 ). The thickness of the collagen often varies from site to site in individual patients and should only be evaluated in well-oriented sections. The normal basement membrane of the colon measures 2 to 5 μm, while in CC the collagen typically has a thickness of 10 to 30 μm. Biopsies from the rectum and sigmoid colon may show less thickening and may be in the normal range. When in doubt, a trichrome stain can be used to highlight the collagenous band and show the irregular nature of its lower border (a feature not seen with normal basement membrane; see Fig. 11-3 ). Care should be taken not to over interpret a thickened basement membrane as CC. Surface epithelial damage with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes should always be present in cases of CC. Intraepithelial neutrophils may be seen, but they are usually less prominent than the intraepithelial lymphocytes. Large numbers of crypt abscesses are probably indicative of either superimposed infection or a separate diagnosis such as ulcerative colitis. Paneth cell metaplasia may be a marker of CC that is more refractory to therapy.

Gross findings

- ■

Usually normal gross appearance

- ■

Rarely linear ulcers or pseudomembranes

Microscopic findings

- ■

Subepithelial collagen deposition (10 to 30 μm vs. normal 2 to 5 μm)

- ■

May be patchy and spare the rectum/left colon

- ■

Collagen encircles superficial capillaries and may have an irregular lower border; shown by trichrome stain

- ■

Surface damage with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes

- ■

Increased lamina propria plasma cells, often superficial

- ■

Occasional foci of cryptitis or neutrophils in surface epithelium

- ■

Little if any crypt distortion

- ■

Paneth cell metaplasia may predict worse prognosis (refractory disease)

Differential diagnosis

- ■

Lymphocytic colitis

- ■

Radiation colitis

- ■

Ischemic colitis

- ■

Mucosal prolapse/SRUS

- ■

Ulcerative colitis

- ■

Crohn’s disease

- ■

Normal mucosa with a thick basement membrane

- ■

Enema effect

Differential diagnosis

A number of lesions may mimic some of the histologic changes of CC, including lymphocytic colitis (LC), chronic inflammatory bowel disease, solitary rectal ulcer/mucosal prolapse, enema effect, ischemia, and radiation colitis. Lymphocytic colitis looks identical to CC except for the absence of subepithelial collagen. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease typically shows more architectural distortion and the fibrosis involves deeper aspects of the lamina propria than is seen in CC. Mucosal prolapse also shows fibrosis in deeper portions of the lamina propria as well as muscular proliferation and crypt distortion. Enema effect may mimic some of the surface epithelial damage seen in CC as well as making it difficult to evaluate the surface epithelium. Ischemia often has fibrosis and hyalinization of the lamina propria that may be misdiagnosed as CC, but the increased plasma cells in the lamina propria and the increased intraepithelial lymphocytes seen in CC will be absent. Radiation colitis also shows hyalinization of the lamina propria, usually with telangiectatic blood vessels and atypical endothelial cells and fibroblasts. The hyaline material does not stain as intensely on the trichrome stain as does the collagen in CC.

Prognosis and therapy

Some patients with CC have a spontaneous remission, while others respond to simple over-the-counter antidiarrheal agents. Most patients, however, require some form of anti-inflammatory therapy (steroids and/or 5-aminosalicylic acid compounds). Rarely, patients with refractory disease may require a diverting ileostomy. The overall course of the disease tends to wax and wane, but it is generally not as severe as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

■

Lymphocytic colitis

Clinical features

There is considerable overlap of both the clinical and pathologic features of LC and CC. Patients typically have chronic watery diarrhea with normal or near normal endoscopic findings. There tends to be less of a female predominance in LC than in CC, while the age range is quite similar.

Many medications, including ranitidine, Cyclo 3 Fort, sertraline, ticlopidine, aspirin, and proton pump inhibitors, have been reported to cause LC. The association between LC and celiac disease is even stronger than the association between CC and celiac disease. These findings again support the notion that luminal antigens induce this colitis. In addition, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) studies have shown an increased incidence of HLA A1, DQ2, DQ1, and DQ3 in patients with LC, as well as other autoimmune processes.

Definition

- ■

Chronic nondistorting colitis typified by increased intraepithelial lymphocytes and surface damage

Incidence and location

- ■

3.1 per 100,000 population

- ■

Generally involves the whole colon, but may have distal sparing

Gender, race, and age distribution

- ■

Males to females, 1:1

- ■

Primarily affects middle-aged to older adults

- ■

Mean age of onset 51 years

Clinical features

- ■

Chronic watery diarrhea with normal or near normal endoscopy

Prognosis and therapy

- ■

Most patients respond to symptomatic or anti-inflammatory therapy

Pathologic features

In general, LC looks just like CC without the subepithelial collagen table. The surface epithelial damage with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes is often more prominent or intense in LC. Just as in CC, there is generally a superficial plasmacytosis without crypt distortion in LC ( Fig. 11-4 ). There may be fewer lamina propria eosinophils in LC than are seen in CC. The surface damage and lymphocytosis may be patchy, while the lamina propria plasmacytosis tends to be diffuse. The pathologist must avoid evaluating the number of intraepithelial lymphocytes overlying a lymphoid follicle, as one should normally see numerous intraepithelial lymphocytes there ( Fig. 11-5 ). One should also recognize that normally there are more intraepithelial lymphocytes in the right colon compared with the left colon. A few foci of cryptitis or a rare crypt abscess may be seen in LC, but more neutrophilic inflammation than this suggests another diagnosis. Recently it was recognized that some cases of LC have less surface damage and more intraepithelial lymphocytes in the deeper crypt epithelium. Another variation of LC has been described with collections of histiocytes and poorly formed granulomas underneath the surface epithelium.

Gross findings

- ■

Usually normal gross appearance

Microscopic findings

- ■

Surface damage with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes

- ■

Increased lamina propria plasma cells, often superficial

- ■

May have occasional foci of cryptitis or neutrophils in surface epithelium

- ■

Little, if any, crypt distortion

Differential diagnosis

- ■

Collagenous colitis

- ■

Resolving infectious colitis

- ■

Colonic epithelial lymphocytosis associated with chronic food- or water-borne epidemics

- ■

Crohn’s disease

- ■

Normal mucosa overlying a lymphoid aggregate

- ■

Lymphocytic enterocolitis

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of LC is somewhat narrower than CC. The resolving phase of infectious colitis can mimic LC, because there can be surface damage and a modest increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes. Lymphocytic colitis-like changes have also been described in an outbreak of chronic diarrhea linked to the water supply on a cruise ship. This so-called colonic epithelial lymphocytosis seemed to have less surface damage than in LC. Reports have also been made of LC-like histology in patients with constipation as well as in patients with endoscopic abnormalities. Hence, it is important for the pathologist to make sure the clinical history is consistent with LC before making this diagnosis. There are also reported cases of Crohn’s disease with patchy areas showing an LC-like pattern. Collagenous colitis may be confused with lymphocytic cases when only rectal biopsy samples are obtained or when the subepithelial collagen table in CC is patchy and fairly thin.

Prognosis and therapy

Therapy for LC is variable and is largely identical to that used for CC. Some patients’ symptoms resolve spontaneously, while others may require over-the-counter diarrheals, bismuth subsalicylate, 5-aminosalicylic acid compounds, or immunosuppressants. Overall, the prognosis is good, because eventually most patients respond to some form of therapy. However, there is a small subset of patients who have LC and sprue-like changes in their small bowel biopsies that seem refractory to all therapy. These patients have been classified as having lymphocytic enterocolitis, although some investigators have raised the possibility that these patients have a lymphoproliferative disorder.

■

Ischemic colitis

Clinical features

Ischemia can give rise to a wide range of clinical presentations depending on the duration and severity of the underlying pathology. While many cases of ischemia occur in older patients with known cardiovascular disease, ischemic colitis can also be seen in younger seemingly healthy people secondary to medications or previous abdominal surgery. Symptoms may range from transient bloody diarrhea or abdominal pain to a full-blown surgical emergency resulting from an infarcted bowel.

While lack of blood flow to the mucosa is the ultimate cause of ischemic colitis, there is a long list of conditions that can lead to this. Ischemic necrosis may be caused by atherosclerosis, low-flow states secondary to hypovolemia, vasculitis, adhesions, various drugs, and even long-distance running ( Fig. 11-6 ). In some instances the drug may induce vasospasm (catecholamines, cocaine), while in other cases the medication may lead to thrombosis (estrogens). Enterohemorrhagic strains of Escherichia coli (such as E. coli O157:H7) can also cause an ischemic-type colitis, presumably resulting from fibrin thrombi that develop during this toxin-mediated infection.

Definition

- ■

Damage to the colon secondary to decreased blood flow

Incidence and location

- ■

3 per 10,000 population

- ■

The splenic flexure and descending and sigmoid colon are the most common sites of ischemia, but any site in the colon can be involved

- ■

The rectum is the least common site for ischemia

Gender, race, and age distribution

- ■

Males equal to females

- ■

Most patients are older than 50 years, but younger patients and even children can have ischemia, depending on the underlying disease processes that may be involved

Clinical features

- ■

Presentation is variable depending on severity and underlying etiology

- ■

Abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, vomiting, and fever may be seen

Radiologic features

- ■

Barium enema shows “thumbprinting”

- ■

CT can show “target lesions”

- ■

Angiography can be used to identify vascular lesions

Prognosis and therapy

- ■

A majority of ischemic colitis cases resolve with supportive care, but 15% to 20% require surgical intervention

- ■

Complications include perforation, peritonitis, and stricture formation

Radiologic features

The classic radiologic finding of ischemia on a barium enema study is that of “thumbprinting.” This finding is produced by marked submucosal edema. Computed tomographic (CT) findings of circumferential bowel wall thickening may also be a marker for ischemia.

Pathologic features

Gross findings

Ischemia typically shows geographic areas of ulceration that may have pseudomembranes. This is often accompanied by marked submucosal edema. Endoscopically this submucosal edema can be prominent enough to mimic a tumor or mass lesion. The watershed areas around the splenic flexure are the most common sites for ischemia, but nearly any site can be involved, including the proximal rectum. Chronic or healed ischemic lesions may form isolated strictures that resemble Crohn’s disease.

Microscopic findings

Acute ischemic lesions of the colon show superficial mucosal necrosis that may spare the deeper portions of the colonic crypts ( Fig. 11-7 ). The remaining crypts typically have a withered or an atrophic appearance. There may be striking cytologic atypia, to the point where care should be taken to avoid overcalling these reactive changes dysplastic. Ischemic colitis may often have pseudomembranes, as well as hemorrhage into the lamina propria and hyalinization of the lamina propria. A trichrome stain can be used to highlight the hyalinization of the lamina propria ( Fig. 11-8 ). While cryptitis and crypt abscesses may be seen, these are usually not prominent. Depending on the severity of the decreased blood flow, these ischemic lesions may regress on their own or lead to perforation and/or stricture formation. The chronic phase of ischemia is often more difficult to diagnose, because the only histologic findings may be strictures and areas of submucosal fibrosis.

Gross findings

- ■

Geographic ulcers or infarcts, pseudomembranes, submucosal edema, strictures

Microscopic findings

- ■

Superficial mucosal necrosis, hyalinized lamina propria, withered or atrophic crypts, pseudomembranes, chronic ulcers/strictures

Differential diagnosis

- ■

Clostridium difficile colitis

- ■

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli

- ■

NSAID damage

- ■

Crohn’s disease

- ■

Radiation colitis

- ■

Collagenous colitis

- ■

Dysplasia

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of ischemic colitis includes infectious lesions such as Clostridium difficile colitis and enterohemorrhagic E. coli , as well as drug-induced lesions such as those caused by NSAIDs and even some chronic colitides such as CC, radiation colitis, and Crohn’s disease. Because pseudomembranes may be seen in both ischemia and C. difficile colitis, it may be particularly difficult to differentiate these two. The presence of a hyalinized lamina propria and withered or atrophic-appearing crypts are specific findings in ischemia that are not seen in C. difficile colitis. In addition, the pseudomembranes tend to be more diffuse in C. difficile and patchy in ischemia. The presence of an ischemic-appearing lesion in the right colon should also make one think of enterohemorrhagic E. coli, especially if fibrin thrombi are present.

Differentiating chronic ischemic ulcers from NSAID-induced damage or Crohn’s disease may be impossible, especially on biopsy material. Radiation exposure often causes arterial damage that can manifest itself as ischemia in the gut. In some instances the hyalinized appearance of the lamina propria in radiation colitis and the subepithelial collagen in CC can mimic the hyalinized lamina propria one sees in ischemia. The presence of telangiectatic vessels and atypical endothelial cells and fibroblasts should help identify radiation colitis, while the inflammatory component of CC should help with its identification. Lastly, the regenerative epithelial changes in ischemia may mimic dysplasia. Recognition of the surrounding ischemic changes is the key to avoiding this pitfall.

Prognosis and therapy

The prognosis for ischemic colitis depends entirely on the underlying etiology of the ischemia, as well as the severity of the process. Ischemia in a long-distance runner is likely to be transient and self-limited, while severe thromboembolic disease may lead to a life-threatening bowel infarct with perforation and peritonitis. Overall, 35% of cases resolve with simple supportive care, while 15% to 20% may require surgery.

■

Radiation colitis

Clinical features

Acute radiation damage is often subclinical, whereas patients with chronic radiation damage may complain of diarrhea, abdominal pain, or rectal bleeding. Patients receiving radiation therapy for cervical and prostate cancer have the highest risk for radiation damage.

Acute radiation injury occurs within hours to days of radiation exposure and is a result of epithelial injury. This damage usually heals within 2 months. Chronic radiation colitis occurs secondary to damage to the mesenchymal tissues of the gut. These changes may remain clinically silent for long periods of time. These lesions can remain symptomatic for the life of the patient.

Definition

- ■

Colonic damage secondary to radiation exposure

Incidence and location

- ■

5% to 15% of patients receiving radiation to the pelvis

- ■

Most common in the rectum

Gender, race, and age distribution

- ■

Older men treated with radiation for prostate cancer

- ■

Middle-aged to younger women treated with radiation for cervical cancer

Clinical features

- ■

Diarrhea, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding

Prognosis and therapy

- ■

Radiation damage is permanent

- ■

May require surgery if steroids or laser coagulation do not work

Pathologic features

Gross findings

Acute

Endoscopy shows edema and a dusky-appearing mucosa.

Chronic

Much of the damage induced by radiation is caused by ischemic damage to mesenteric vessels; ulcers, strictures, fistulas, and adhesions may be seen. Endoscopically, there is typically patchy erythema, which is secondary to telangiectasia of the mucosal capillaries.

Microscopic findings

Acute

Acute radiation damage is rarely seen, but the changes are those of epithelial damage, increased apoptosis, decreased mitoses, and regenerative atypia. Increased numbers of eosinophils may also be seen.

Chronic

In addition to telangiectasia of the mucosal capillaries, chronic radiation damage often has areas of hyalinization around these dilated vessels with atypical “radiation fibroblasts” ( Fig. 11-9 ). The endothelial cells may also show similar radiation-induced atypia. Some degree of crypt distortion and even foci of cryptitis may be seen. Superimposed changes of ischemia may also be present.