Definition of GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as at least weekly heartburn, acid regurgitation, or both, or extraesophageal symptoms with impairment of quality of life.

1 GERD is quite common and affects around 20% to 30% of the population in industrialized countries. In the United States, 21% to 44% are said to suffer from regular heartburn, while GERD is actually diagnosed in 10% to 20%, with mucosal breaks (endoscopic erosions) being present in 2% to 5% of all refluxers. Around one-third of the affected individuals seek professional help. It is now clear that lifestyle factors, in particular obesity and smoking, are associated with increased reflux symptoms.

2 In overweight individuals, the presence of a hiatal hernia increases the risk of reflux disease about ninefold compared to individuals without hiatal hernia.

3GERD is readily diagnosed in most patients from the characteristic history, and is treated by medications that decrease the amount of gastric acid. These range from over-the-counter antacids to medications reducing gastric acid secretion, of which there are two major classes. H2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) block the secretion of acid by blocking the histamine 2 receptors (hence H2) that mediate acid secretion in response to gastrin (released from the gastric antrum and duodenum) or acetylcholine. They usually have the suffix -tidine (cimetidine, ranitidine, etc.). Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), as their name implies, inhibit secretion of hydrogen ions (protons) from parietal cells, and tend to be more potent although a little slower to act. They usually have the suffix -prazole (omeprazole, esomeprazole, lanzoprazole, etc.). Response to therapy is usually almost immediate, and further serves as a confirmation of the diagnosis.

Some patients have periodic symptoms and can take medications as the need arises, but for many it is chronic, so medications may be lifelong. Some patients become aware of the increased quality of life with PPIs when they undergo Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, of which a PPI is a key ingredient. When the course of therapy ceases, their symptoms quickly recur so they become “hooked” on PPIs. While these are a remarkably safe group of drugs, they do increase the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) infections, and in the long term, gastric fundic gland polyps, which fortunately appear quite harmless. PPIs may increase the risk of osteopenia and fractures. In patients on longterm high-dose PPIs, the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency is increased, as both acid and B12 are required for its absorption, and the secretion of both from parietal cells is diminished by PPIs. Endoscopy, potentially with biopsies, is therefore reserved for patients who are not responding to therapy or have atypical symptoms such as chest pain in which it is unclear whether this is of cardiac, esophageal, or some other cause. While endoscopic erythema, erosions (mucosal breaks), and ulcers can all be seen, patients may have GERD without these changes (nonerosive reflux disease [NERD]), although on biopsy a variety of abnormalities can be found in these patients. Some of these patients appear to simply have exquisite esophageal sensitivity to acid.

There are numerous other causes of esophageal ulceration, especially medication, which may become stuck in the esophagus (pill-induced esophagitis), so that a history of medications used is also key (discussed subsequently). Infections (herpes, cytomegalovirus [CMV]) can also be painful and cause ulcers while there are numerous other less common causes (

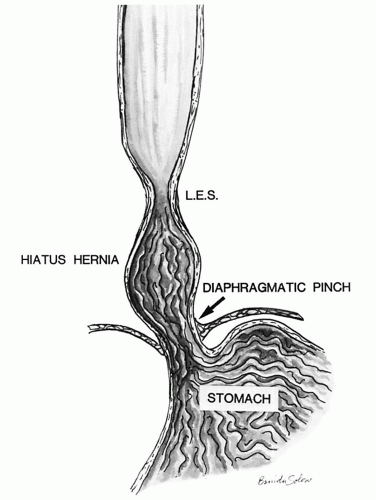

Table 10-1) that can affect the esophagus. Further, GERD has numerous complications but especially Barrett’s esophagus (BE), which increases the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma, usually in association

with hiatal hernia, which tends to promote free gastroesophageal reflux, as the additional safety valve of the diaphragmatic pinch is less effective. Other patients have motility problems that allow reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus or have a degree of peristaltic failure.

Symptoms of GERD

The leading symptom of GERD is heartburn, which needs to be differentiated from other causes of retrosternal pain, such as dysphagia, odynophagia, and cardiac pain. Further, GERD can lead to extraesophageal symptoms such as hoarseness, laryngitis, dyspnoea, cough, bronchitis and reflux-induced asthmatic disease, dental erosions, and retrosternal pain that need to be differentiated from ischemic heart disease.

1 The frequency of these extraesophageal symptoms is probably underestimated in the population, but on the other hand laryngitis as a sequel of GERD is probably overestimated.

4Correlation between GERD, symptoms, and endoscopy. An ill-defined proportion of patients clearly have reflux-induced esophageal lesions endoscopically, but are asymptomatic, while another group have symptoms but little to see endoscopically (nonerosive [endoscopy-negative] reflux disease—NERD/ENRD).

5,

6 A more troublesome group of patients appear to have persistent symptoms despite being on high-dose PPIs but have nothing evident endoscopically. These patients may have “visceral hypersensitivity” to esophageal acid, possibly mediated through dilated intercellular spaces (DISs) allowing acid (and other molecules) to pass through the pericellular space into the lamina propria and the nerves there.

7 DISs are readily visible on biopsies, but it is unclear where physiology stops and pathology starts.

Therapy. In classical reflux disease, symptoms are treated with antisecretory therapy, usually PPIs.

A 1-week course of PPI that proves to be therapeutic can serve as a diagnostic test, and endoscopy is limited to those that do not respond, or have atypical symptoms, so that biopsies are not usually necessary.

Long-term therapy for GERD and prognosis. If longterm (usually lifetime) treatment with PPIs

8 is refused, there are intraluminal endoscopic procedures available besides open or endoscopic fundoplication. What all of these procedures have in common is that they narrow the distal esophagus to imitate the distal esophageal sphincter to avoid regurgitation of gastric contents into the esophagus. Many of these endoscopic procedures have fallen out of favor because of either failure or complications. The surgical equivalent of these techniques has a small but definite mortality, related to some extent on the experience of the surgeon. However, patients who benefit most from a fundoplication are also those who show the best response to medical treatment. Also, fundoplication does not last forever (they become lax over time) and ultimately about 60% of operated patients need PPIs to manage symptoms. Approximately 20% of individuals who undergo surgical fundoplication may suffer from a gas-bloat syndrome where there is difficulty with eructation and air feels trapped and some develop dysphagia secondary to the fundoplication wrap being too tight, and dilation is required. General health (losing weight, sleeping with bed head raised) recommendations do not have long-lasting benefits in reflux disease. Nevertheless, there are always patients who report symptom relief after losing weight or after changes in lifestyle.

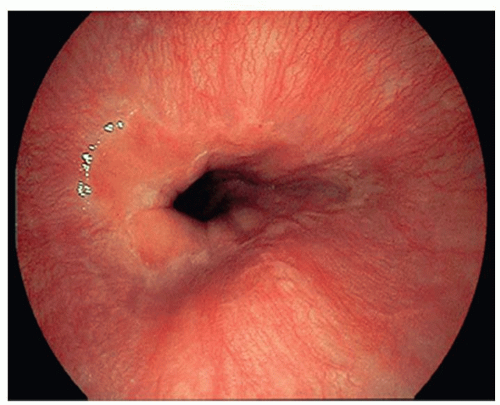

The Gastroesophageal Junction and Z-Line

One major problem is the difficulty in the definition of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), which differs worldwide. Practically by far, the most important definition is that used endoscopically in which the GEJ is now defined as the upper limit of the proximal gastric folds. Endoscopically, the Z-line is defined as the transition of columnar epithelium into stratified squamous epithelium. The Z-line is usually irregular (hence Z-line) and should be within the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which itself extends for several centimeters (see

Chapter 9). Histologically, squamous mucosa may be in direct continuity with:

1. Gastric cardiac, cardio-oxyntic, or less frequently oxyntic (acid-producing) mucosa

2. Undermining cardiac glands below the squamous epithelium (that can also be seen in treated GERD)

3. The presence of multilayered (hybrid) epithelium

4. Pancreatic metaplasia

The last three are usually not recognizable endoscopically.

In Japan, the GEJ is defined by the distal end of esophageal palisade vessels. However, this is an approximation, as the end of these vessels can be present above, at, and even below the Z-line in normal individuals.

Etiology and Pathogenesis of GERD

Temporary mild reflux of gastric contents into the distal esophagus is thought to be physiologic. Pathologic reflux is diagnosed clinically whenever, in the supine position, a prolonged contact of gastric refluxate is present combined with a pH <4 for more than 4% of 24 hours (at least 1 hour a day). It is believed that low basal lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure

along with increased transient LES relaxations (tLESR) cause reflux disease. Besides increased relaxation, or insufficiency of the distal esophageal sphincter, there are other factors that can either cause or unmask prior existing reflux disease. These include the presence of a hiatal hernia (

Fig. 10-1), the increased acid secretion that often follows

H. pylori eradication therapy (or rarely Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), obesity, medications that decrease the LES pressure,

9 possibly excess alcohol, impairments of esophageal emptying (motility disorders), impaired salivary and esophageal gland secretions, duodenogastric reflux, delayed gastric emptying (mostly in diabetic patients with autonomic neuropathy), stenosis or strictures, impaired esophageal resistance to acid, and failure of clearance. Numerous changes occur in the esophageal nerves (described under morphologic changes in nerves).

Gastric heterotopia (inlet patch) in the proximal esophagus can contribute to acid secretion, depending on its size and the presence of oxyntic mucosa.

For NERD, dilated intercellular spaces (DISs—see subsequent discussion) and visceral hypersensitivity are postulated mechanisms. The DIS experimentally can be induced by acid plus sodium nitrite,

10 which is present in saliva.

11,

12 In addition, the presence of duodenal contents containing bile and activated pancreatic juice, both known to be considered as etiologic factors in generating BE, might also be involved in the etiology of reflux disease. In large-scale studies, alcohol and smoking appeared not to be risk factors for reflux disease or its complications. General recommendations such as reducing weight may not impact reflux disease but in some contribute to reduced symptoms and of course make sense for general health.

The role of hormonal effects is controversial: Gastrin and cholinomimetics increase the lower sphincter pressure, whereas secretin, glucagon, cholecystokinin, and prostaglandins inhibit the effect of gastrin.

13

Los Angeles Grading System for Reflux Disease in Squamous Mucosa

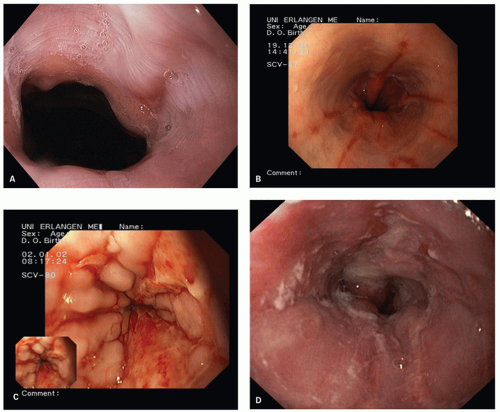

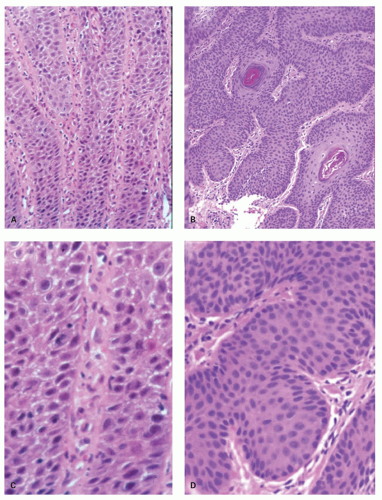

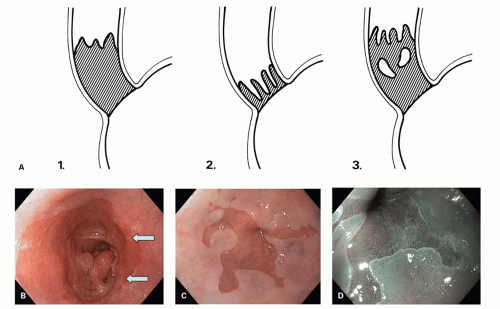

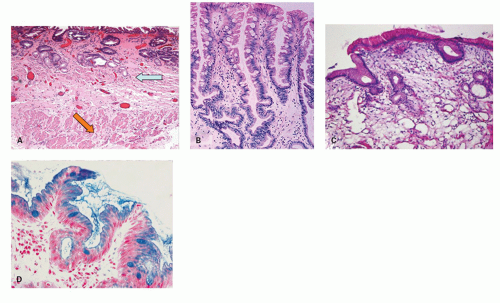

The Los Angeles classification (

Fig. 10-2A-D) grades changes in squamous mucosa as follows:

Grade A—One or more mucosal breaks (= erosions) no longer than 5 mm, none of which extends between the tops of the mucosal folds

Grade B—One or more mucosal breaks more than 5 mm long, none of which extends between the tops of two mucosal folds

Grade C—Mucosal breaks that extend between the tops of two or more mucosal folds, but which involve <75% of the esophageal circumference

Grade D—Mucosal breaks that involve at least 75% of the esophageal circumference

Proposed additions that would precede grades A to D

15 are also occasionally used:

Grade N— Reflux disease with normal endoscopic appearance and absence of minimal signs and mucosal breaks

Grade M— Minimal changes other than mucosal breaks

In Europe, the

Savary-Miller classification is often used.

16 However, there have been several modifications, and interobserver variation is considered poor.

The MUSE classification (

Metaplasia,

Ulcer,

Stricture,

Erosion)

17 is very logical but not used.

For routine clinical practice, in endoscopic examination, the esophagus in patients with GERD, only five things are relevant:

1. Are erosions (called mucosal breaks in the LA system) present?

2. Is stenosis present?

3. Is BE present?

4. If BE is present, the detection of dysplasia/neoplasia.

5. Are subtle/minimal features present (redness, red streaks) that might reflect NERD?

Endoscopic grading is of less interest in a clinical routine setting, but erosions (mucosal breaks) may be relevant,

while stenosis may need to be dilated and BE might need PPIs (even if asymptomatic) and follow-up surveillance.

Nonerosive Reflux Disease and Its Pathology

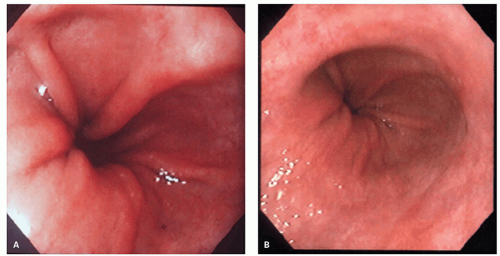

It is now accepted that the vast majority of patients with reflux disease do not present with esophageal lesions (mucosal breaks/erosions) but do suffer from reflux symptoms.

1 These patients are believed to belong to a group of patients with nonerosive (endoscopynegative or with minimal changes) reflux disease.

6 However, using magnifying zoom endoscopy (magnification between 110 and 150 times), it has been shown that minimal lesions that do not fulfill the criteria of a mucosal break that occur in this group of patients are for the most part dilated intraepithelial capillary loops in the lower esophagus.

18 Further, some patients may just be hypersensitive to esophageal acid.

This group can further be subdivided into true normals and those with minimal lesions such as vascular ectasia, an increase in DISs, and an increase in basal cell height or papillary height that is not in the pathologic range yet decreases considerably on PPIs. This suggests that NERD may consist of both patients with minimal lesions that can be demonstrated with appropriate endoscopes and a further subgroup of patients who may be very sensitive to acid (visceral hypersensitivity) but who are completely normal endoscopically.

19 In both groups of patients, PPIs cause all of these changes to disappear, and the normal palisaded vessels at the Z-line become visible again, while many of the hypersensitive groups also become symptom free. The diagnosis of endoscopic-negative reflux disease is still somewhat difficult. pH-metry is considered to be the “gold standard” but is uncommonly carried out, although it can be done with a portable device at home.

Histology can help in this respect, depending mostly on the site of the biopsy. Biopsies close to the GEJ often show typical features of GERD but in biopsies close to the Z-line these probably have to be interpreted as normal, even though in some it represents genuine reflux disease as there may well be some differences between normal and abnormal (see previous discussion

18,

40,

41).

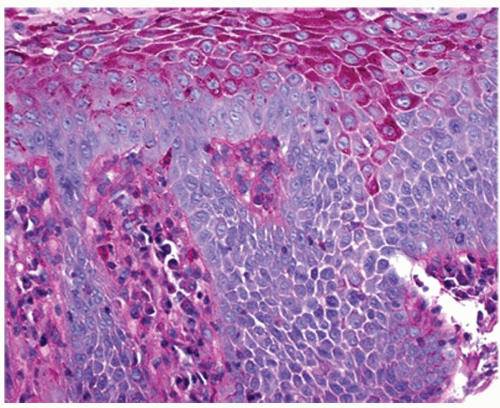

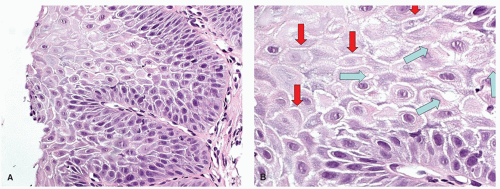

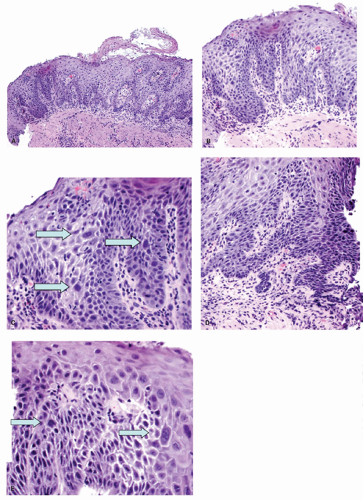

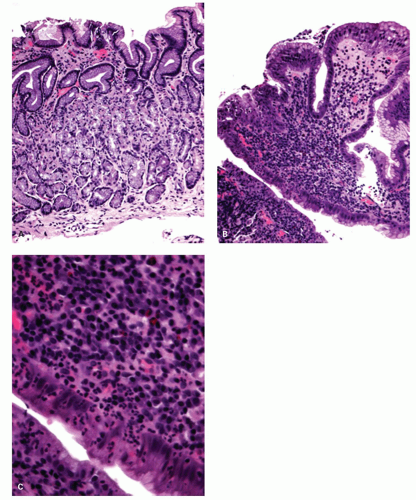

The other features that can be found in patients with NERD are DISs (spongiosis) of the epithelium. This accentuates the intercellular prickles (“ladders”) between two adjacent cells, but at the intersection between three cells these form intercellular canals that appear rounded (bubbles) (

Fig. 10-3). This intercellular edema is a good marker of epithelial damage, so it is not specific and is also common in eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). In addition, small amounts of intercellular edema are common and probably normal, so when normal becomes pathologic is unclear. Care must be taken to not misinterpret cytoplasmic vacuolation as DIS.

Where to Biopsy for GERD and Criteria Used

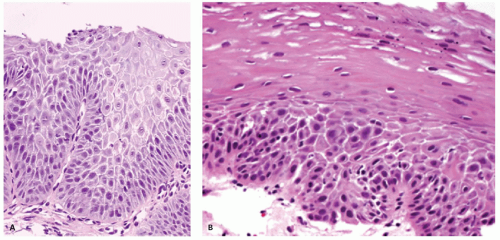

Erosions. Although erosions are not often biopsied to confirm their presence if they are multiple or atypical, consideration may be given to exclude other treatable causes such as

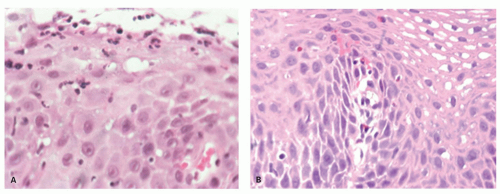

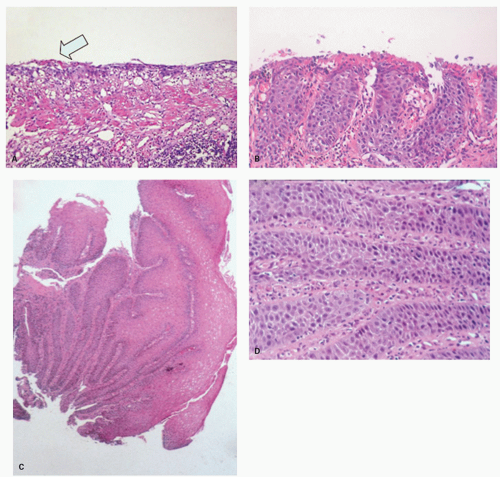

Candida or herpes. Biopsies from erosions are easy to interpret when at the edge of a biopsy, as they consist of granulation tissue, sometimes with atypical stromal cells. However, small fragments may show only basal cells and underlying capillaries representing granulation tissue that is being re-epithelialized, some of which correspond to the red streaks seen endoscopically (

Fig. 10-4A). Marked reactive changes may also be problematic as they may be confused with invasive squamous carcinoma. Initially they are part of re-epithelialization (

Fig. 10-4B-E). The regularity of these “prongs” is the key to their reactive nature. More usually there are typical reactive changes with overt basal cell hyperplasia and papillary elongation (

Fig. 10-4).

If no erosions are seen, biopsies from just above the Z-line can show evidence of healing erosion (

Fig. 10-4),

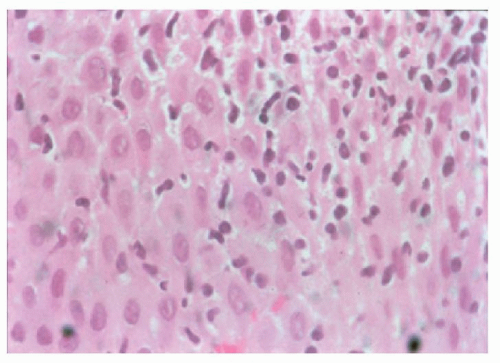

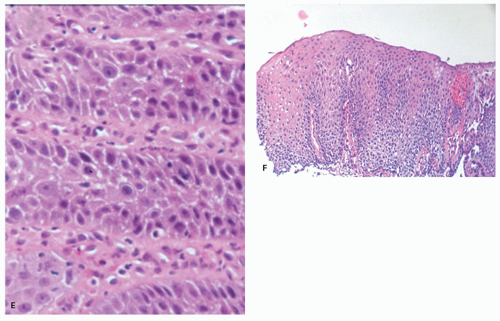

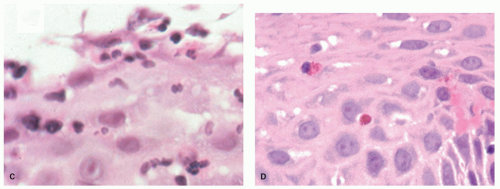

neutrophils that are initially superficial (

Fig. 10-5), and a sprinkling of

eosinophils (

Fig. 10-5) that are less than those seen in EoE (<25 in 1 high-power field [HPF] or 15 in each of 2 in the same biopsy, and usually far fewer than this) but are usually sufficiently uncommon that one usually has to search for them. There is an overlap with EoE (see that section); patients with typical clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of EoE are usually treated as such but where these are not all present (and in some patients with typical features of EoE), they are often treated for GERD, at least initially. A rare eosinophil is thought to be acceptable in adults, although they remain uncommon, but in children eosinophils are always regarded as abnormal. An excess of

intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) (lymphocytic esophagitis) is seen in GERD but appears

to be neither sensitive nor specific; nor has the cut-off for normals been well defined. As such, this cannot reasonably be used to make a diagnosis of GERD.

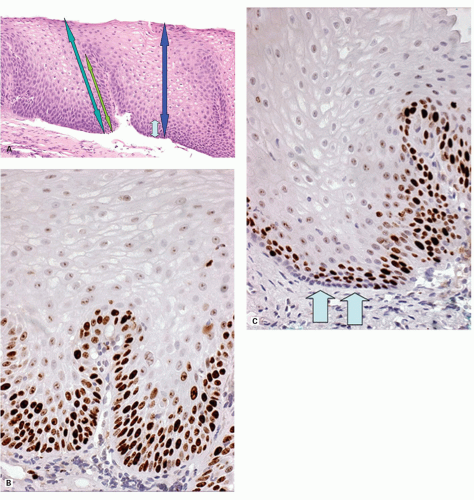

Biopsies 3 cm above the Z-line may show reactive epithelial changes (basal cell hyperplasia, elongation of papillary length) (

Fig. 10-6). Biopsies also exclude imitations of reflux disease (

Table 10-2) even if there are minor changes such as red streaks or areas of redness,

22 and to recognize BE with or without dysplasia or carcinoma. Theoretically, a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain can also be used to delineate the basal layer as these cells are glycogen deficient (

Fig. 10-7), but this is rarely used as the hyperplasia is obvious on H&E sections (see

Figs. 10-4F and

10-8). Another feature of basal cells is that they have a high proliferative index (see

Fig. 10-6). In comparison, not only does normal mucosa have a much lower proliferative index, but in a Ki-67 immunostain the basal layer is unstained, but this disappears as soon as proliferation increases, suggesting that these may be part of the stem cell population of the esophagus.

Traditional biopsy sites. Distal esophageal biopsies are usually taken at the Z-line or 3, or 5, or 7 cm above the Z-line (depending on the author), but are said to play a minor role in diagnosis because in early papers basal cell hyperplasia and papillary elongation may be seen physiologically in the distal 3 cm.

23 The closer these are taken to the Z-line the more likely these reactive changes are assumed to be present. It is likely that most of the regenerative changes are found between the right esophageal and the rear esophageal wall

20 due to the asymmetrical structure of the LES. This seems to be the region where the valve-like mechanism of the LES opens first.

24 However, this does not take into account that the other changes associated with GERD are all

maximal close to the Z-line, so this is where biopsies should be taken to detect erosions or their healing phase (often red streaks), neutrophils, eosinophils, and markedly DIS even when the mucosa appears absolutely normal. Thus biopsies from this region should show more changes compared to other quadrants.

In the squamous mucosa, biopsies for features of GERD should therefore be taken

1. immediately above the Z-line for erosions, neutrophils, eosinophils, and DIS, preferably from the right esophageal wall (basal cell hyperplasia or papillary hyperplasia in this zone have to be interpreted as being within normal limits).

2. 3 cm above the Z-line for traditional reactive changes in the squamous mucosa.

3. from the mid or upper esophagus when EoE is in the diagnosis, hopefully to demonstrate their proximal persistence in that disease.

Cardia biopsies. A little-used criterion is the presence of inflammation limited to the cardia. The rationale for taking biopsies from the cardia is that there are only two major causes of cardiac inflammation: that associated with

H. pylori and that associated with GERD. However to establish the latter, it is necessary to also take standard biopsies for

Helicobacter from the gastric antrum and body—the latter are particularly important if patients are taking PPIs, and organisms may only be found in oxyntic mucosa. In the absence of inflammation in the remainder of the stomach, cardia inflammation is assumed to be secondary to GERD.

25 A similar theoretical argument can be made with the incidental finding of intestinal metaplasia in cardiac biopsies; this should either be associated with intestinal metaplasia in the distal stomach, and therefore part of more widespread

gastric intestinal metaplasia, or limited to the cardia, and be GERD related.

Histologic Diagnosis and Criteria for GERD in Biopsies

The following criteria are used in the morphologic diagnosis of reflux disease; however, as with inflammatory diseases elsewhere, no criteria are specific for reflux disease, and can be seen in other diseases also, causing erosions and ulcers such as infections (e.g., Candida, herpes simplex virus [HSV], cytomegalovirus [CMV]), medications causing ulceration (NSAIDs, bisphosphonates, etc.) that tends to be higher in the esophagus, although not often enough to be relied on, and rarely other causes (e.g., Crohn’s disease). (See subsequent discussion.):

1. Erosions or ulcers, usually close to the Z-line (other causes: infections, medication)

2. Re-epithelializing erosions (regenerative papillae elongation with attenuated overlying epithelium, and then with marked hyperplasia of the basal layer) (see

Fig. 10-4)

3. Neutrophils (same differential diagnosis as 1) (see

Fig. 10-5)

4. Eosinophils (differential is primarily EoE if numerous) (see

Fig. 10-5)

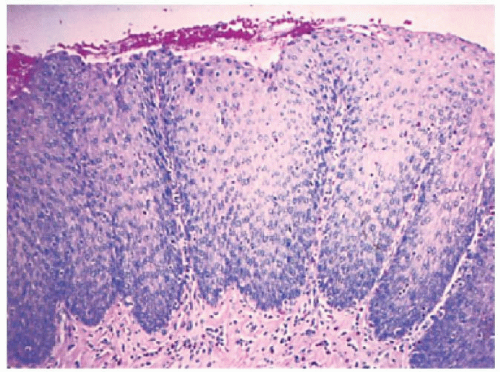

5. Reactive epithelial changes—basal cell layer >15% to the surface or papillary height >two-thirds of the way to the surface (3 cm or more above the Z-line only)

Evaluating reactive changes. In practice, no one measures reactive changes other than in research protocols, but the “rule of thirds” works well. The mucosa is divided mentally into thirds. Papillae extending into the upper one-third are abnormal. The basal one-third is mentally halved. Basal cells extending into the upper third of these are abnormal (in practice, 16.7% of the epithelial thickness, but close enough). The upper end of the basal cell layer is where the distance between the nuclei exceeds their diameter that is, where it becomes possible to fit in a nucleus between nuclei (see

Fig. 10-5). This can also be demonstrated using the presence of glycogen (PAS stain) (see

Fig. 10-7) that accumulates in cells above the basal layer, but this is rarely used. In a well-orientated biopsy, both basal cell hyperplasia and papillary elongation can be evaluated with relative ease (see

Fig. 10-8).

Less Reliable Criteria

1. Increased peripapillary hemorrhage (increased fragility of capillaries) (

Fig. 10-9)

2. Presence of so-called balloon cells (acid-damaged squamous cells)

3. Eosinophilic “densification” of superficial squamous epithelium

4. DISs (likely a sensitive marker of any sort of epithelial damage but no good data on how much is normal)

5. Increase in IELs

Standardized criteria have been difficult to achieve as few of the criteria are specific for reflux disease, although very sensitive markers of esophageal damage.

23 In practice, the most relevant (specific) criteria are thickness of the basal cell layer (>15%) and proportional length of papillae (>2/3),

26,

27,

28 the latter invariably coming out as the best criteria in clinical studies. This may be useful as it suggests that the presence of an erosion or ulcer without immediately adjacent reactive changes in the squamous mucosa may be an indicator of acute damage (pills) rather than more chronic intermittent disease (reflux).

Dilated Intercellular Spaces It is clear that DIS (spongiosis) are a very sensitive marker of esophageal damage, and are seen especially in GERD, EoE, and “pill”-associated damage. However, the literature is relatively vague on criteria for their use. It has been suggested that although this initially referred to dilatation of the round spaces where pericellular spaces between more than two cells join (“bubbles”), this can also be applied to the spongiotic zone between two cells (“ladders”).

29 Further, a degree of DIS can always be seen in the basal and prickle layers, so a small amount of this is always normal.

The question then is when can this be regarded as pathologic. In one study using oil immersion and electron microscopy, mean diameters were 0.58 ± 0.16

µm for controls, 1.07 ± 0.30 mm for NERD, and 1.29 ± 0.20

µm for erosive disease. The optimal cut-off value from receiver operator characteristic analysis was 0.85

µm.

30,

31,

32 There are also data showing that DIS get smaller following antisecretory (proton pump) therapy, but this happens to some extent in controls as well as in patients, suggesting that DIS are largely acid reflux related.

30 Anecdotally, we have found that numerous markers of intercellular junctions can facilitate demonstration of DIS including desmocollins, desmogleins, cadherins, catenins, occludins, and claudins. However

β-catenin, which is available in many laboratories, works well and reliably until one can routinely identify these changes at routine H&E light microscopy.

Grading reactive epithelial changes. The original criteria for reactive esophageal squamous changes (basal cell hyperplasia, papillary elongation)

26 were subsequently graded by Elster,

33 which is difficult if biopsies are not well orientated, but grading has proven useful in routine practice. The system was

Grade I: The thickness of the basal cell layer reaches up to 10% of total epithelial thickness, papillae reach up to 40% of total epithelial thickness (i.e., normal).

Grade II: The basal cell layer reaches up to 30% (abnormal) and papillae reach up to 60% of total epithelial thickness (still just normal).

Grade III: The basal cell thickness is more than 50% and papillae reach up to 90% of total epithelial thickness.

In virtually all studies where both of these criteria have been measured, papillary elongation (height) is the most reliable criterion. A potential weakness of this system is that using papillary height, the abnormal range is in grade III, whereas using basal cell hyperplasia it is in grade II.

Signing Out Reactive Changes in Biopsies In routine practice, no criteria really need to be graded, although frequently that is the case, as it is almost second nature for pathologists to add “mild, moderate or marked/severe” as a prefix to anything that is a variable criterion. At the mild end, the pathologist may be trying to be helpful in providing a diagnosis. However, if the squamocolumnar junction is included in the biopsies then unless there is evidence of an erosion, all changes based entirely on the morphology of the squamous mucosa may be physiologic. While it is usually easy to say that basal cell hyperplasia or papillary elongation or marked dilatation of intercellular spaces (together often called “reactive changes”) are present, the issue is in their interpretation. It is not incorrect to say that they are “consistent with reflux disease,” as this may be true. However, this can be frankly misleading as they are also quite consistent with being within normal limits. One approach is simply to state that “reactive changes are present but these are normal in this location.” Of course, the additional presence of occasional neutrophils or eosinophils changes this immediately, but any change is based entirely on the presence of these cells, the changes in the squamous mucosa being irrelevant. Conversely, if it is clear that the biopsies come from 3 cm or more above the squamocolumnar changes, then they are pathologic, although a degree of caution is required because reactive changes can have numerous causes other than GERD, especially medications, as well as infection. Caution should therefore be exercised before mindlessly stating that reactive changes are “consistent with GERD” as it may be overtly misleading.

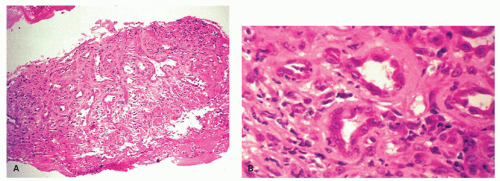

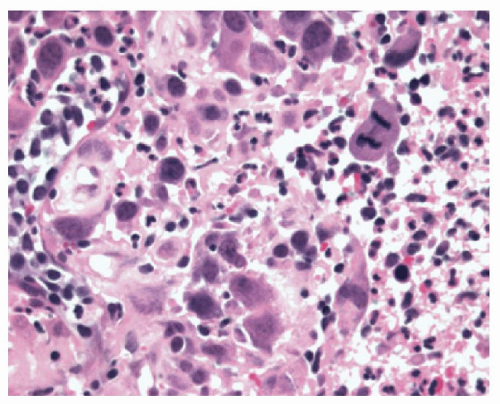

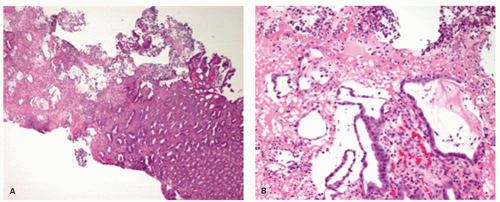

EROSIVE ESOPHAGITIS. In erosive esophagitis, the mucosa is reddened, the lesions are covered by debris, and whitish slough is found. Histologically, the margin of esophageal lesions shows the most marked regenerative changes reaching into hemorrhagic or necrosis with marked active inflammation including neutrophils, eosinophils, and less frequently lymphocytes and plasma cells. By definition, erosions do not extend into the submucosa while ulcers do. However, as the lamina propria underlies the epithelium, it is possible to completely lose the epithelium without satisfying the pathologic definition of an ulcer. This is usually impossible to assess in biopsies that may show only hyalinized lamina propria or granulation tissue

(

Fig. 10-10), so it is usually assessed more precisely endoscopically.

Interestingly, although it would be reasonable to think that GERD-associated ulcers occur in association with reactive changes in the adjacent squamous mucosa, as opposed to no reactive changes, our own experience is that this is not the case, and that in biopsies from clinical studies from patients with erosive esophagitis who have a well-controlled drug history, that GERD-associated ulcers are frequently accompanied by a virtually normal adjacent mucosa. Further, biopsies from “mucosal” breaks may show a variety of changes from genuine erosions and ulcers through reactive changes to inflamed and normal mucosa. Whether the latter represents inadequate sectioning through the block or an endoscopic “miss” is unclear; the esophagus is constantly moving with respiration and heartbeat so is not the easiest organ to biopsy accurately. Therapy with PPIs is the therapy of choice.