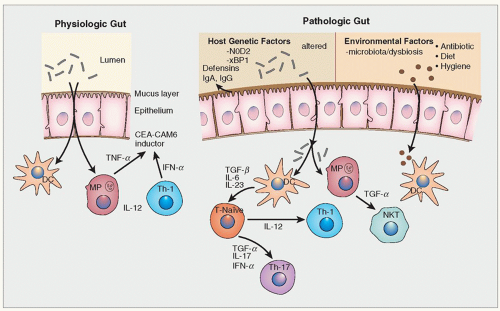

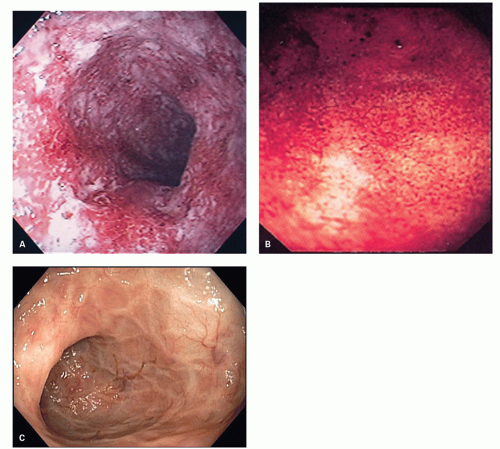

In general, the severity of the mucosal changes in surgical specimens is usually greatest in the distal large bowel and tends to diminish proximally. Even in pancolitis, the disease is usually more severe in the left colon and rectum. This pattern is very useful when seen in sequential biopsies. Macroscopically, the proximal limit of the disease most frequently shows an abrupt transition from disease to normal mucosa, but a gradual change is more usually seen histologically.

Microscopic pathology

Variation in Time and Disease Evolution The chronic and intermittent nature of UC with periods of exacerbation and remissions makes it convenient to divide the microscopic appearances into active disease, resolving disease, and disease in remission (quiescent colitis).

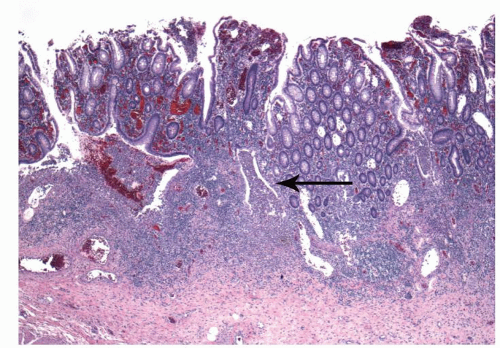

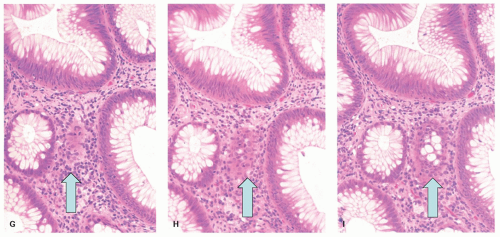

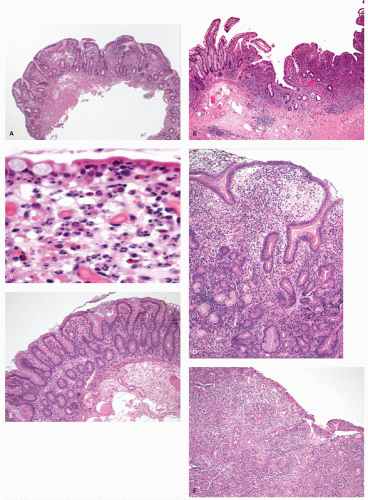

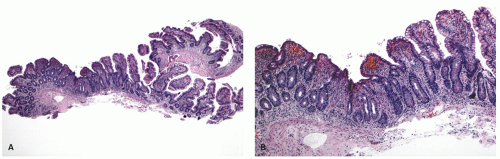

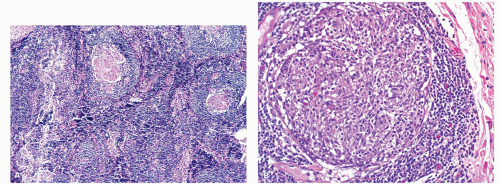

ACTIVE COLITIS. In active colitis, the most striking features are that the two major features required for a diagnosis of IBD are present, namely:

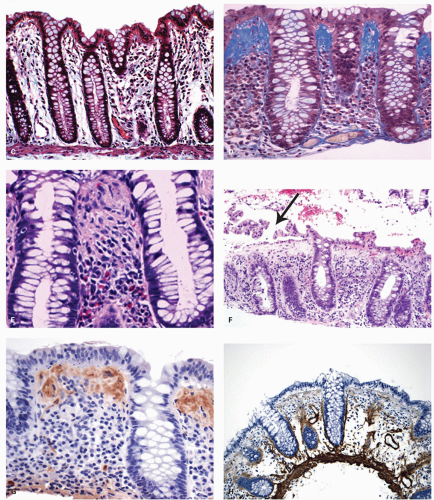

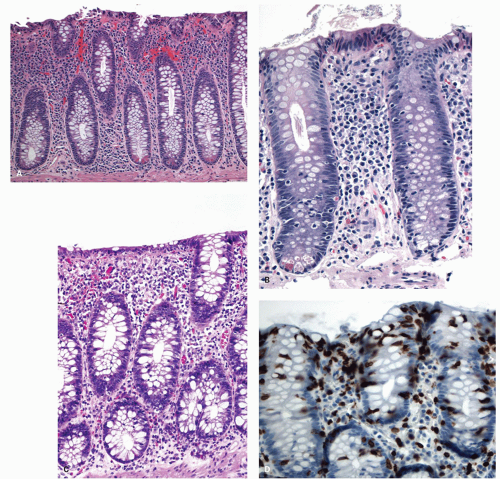

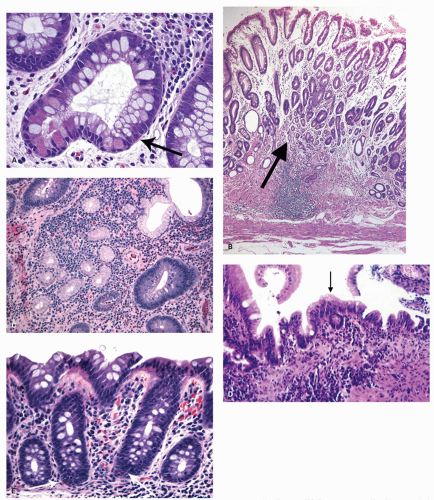

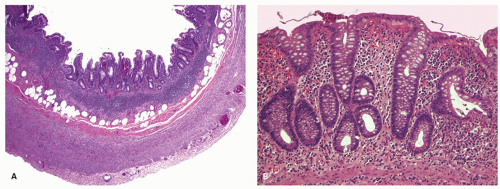

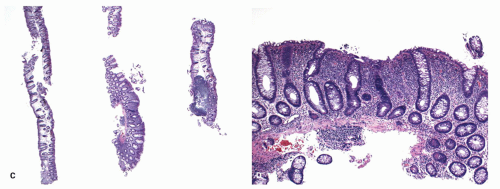

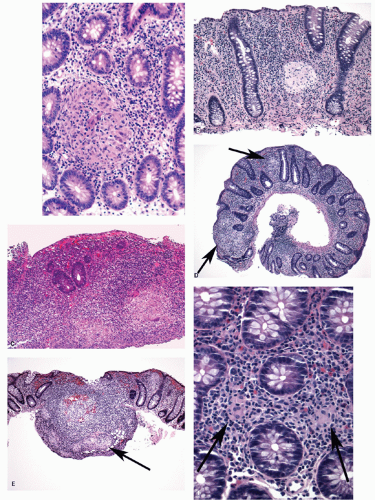

a. Crypt architectural distortion in the involved segments including any accepted additional lesions when present (

Fig. 18-14) (e.g., cecal patch or periappendiceal inflammation). In addition, Paneth cell, and rarely pyloric metaplasia may be present.

b. A diffuse chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate extending to the level of muscularis mucosae, the most reliable feature being the presence of dense plasma cells in the deeper part of the lamina propria (

Fig. 18-14). However, around the ileocecal valve, this feature may be present normally in adults.

These two features establish that the mucosa has been previously damaged resulting in architectural distortion, and that long-standing chronic inflammation is present. While these two features can also be seen in chronic infections (e.g., tuberculosis, amebiasis), in Western societies, or where these diseases are rare, IBD is by far the most common cause.

Once this has been established, the next feature is the type of underlying IBD. This is established by the distribution of disease in serial biopsies, ideally

terminal ileum to rectum from the major anatomical sites, (terminal ileum, ascending, transverse, descending, sigmoid colon, and rectum) in separate containers labeled as to site. UC involves the rectum and extends for a variable distance proximally, and this applies both to the architectural distortion and inflammatory infiltrate. Conversely, CD frequently has a focal distribution and often spares the rectum (see subsequent section).

Activity in UC is gauged by the presence of:

c. Neutrophils that tend to infiltrate into the crypt epithelium (cryptitis) and into the lumen (crypt abscesses), with concomitant mucin depletion of the crypts. In UC, while lamina propria neutrophils can often be found, characteristically, they immediately appear to pass into crypt epithelium, often toward the lower or midpart of the crypts. This is in contrast to CD where neutrophils remain in the lamina propria, but if epithelium is infiltrated, it tends to be quite focal, with one part of the biopsy being severely affected, while the remaining can be relatively normal.

Other features that may be present include:

d. Congestion and dilatation of the capillary blood vessels. The vascular changes and mucosal friability account for much of the bleeding tendency experienced during endoscopic examination.

In practice, the diagnosis of active UC in biopsies is highly characteristic, and virtually a low-power diagnosis. Note that in the above description, the words “nonspecific” are not found either as a descriptor of the inflammation (no “nonspecific acute and chronic inflammation”) or in the diagnosis. The features are those of active IBD and highly suggestive of active UC. The features are not “consistent with nonspecific ulcerative colitis.” Indeed, there is nothing “nonspecific” about these features.

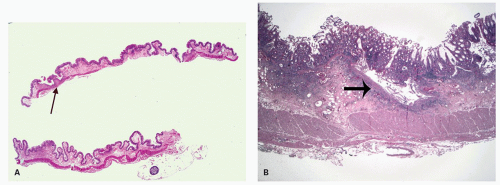

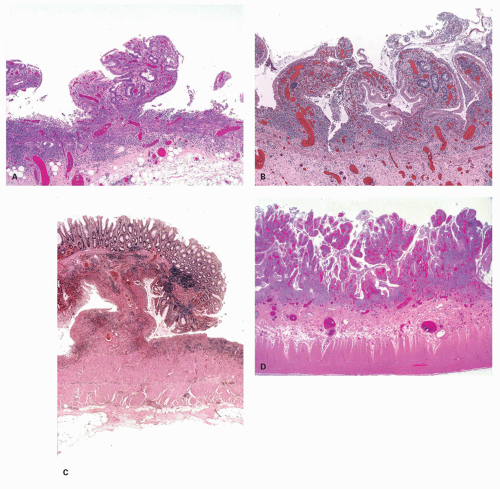

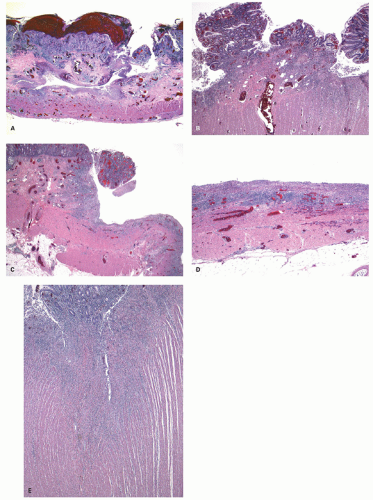

The mucosa appears thickened and the surface epithelium may take on an undulating or low villiform appearance (

Fig. 18-14A,B). The inflammation may extend into the superficial submucosa, but the muscularis propria and serosa remain free of inflammation except in severe or fulminant colitis (

Fig. 18-14B). The presence of inflammation extending into the superficial submucosa on biopsies is not a reliable way of differentiating UC from CD, although higher density of the inflammatory infiltrate in the submucosa is more common with CD.

In more detail, features found are:

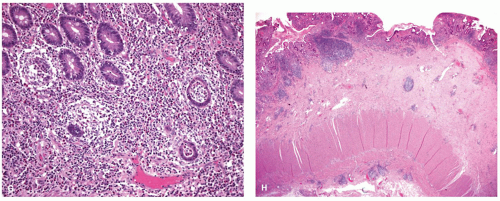

Architectural changes: One of the most characteristic features of IBD, which differentiates it from other forms of acute injury to colon is distortion of the mucosal architecture as a result of chronic and persistent inflammatory damage to the epithelium and attempts at regeneration. The damage to the crypts produces abnormal-shaped crypts with branching or budding, and sometimes shortening (

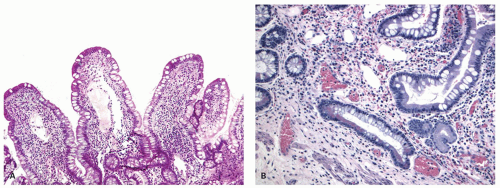

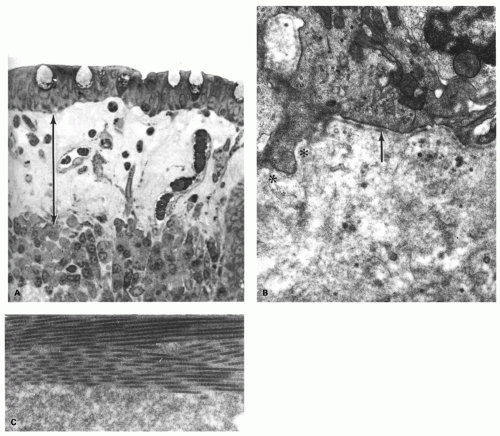

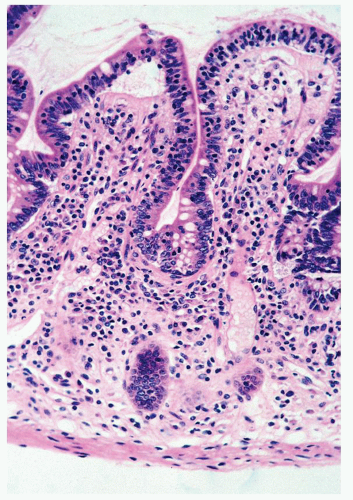

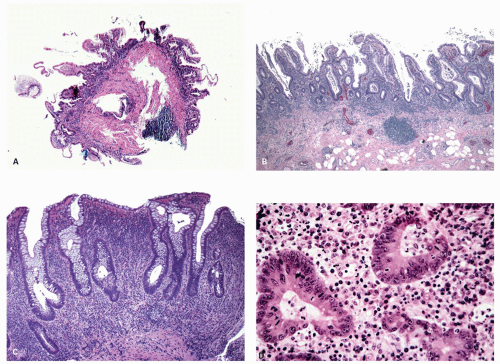

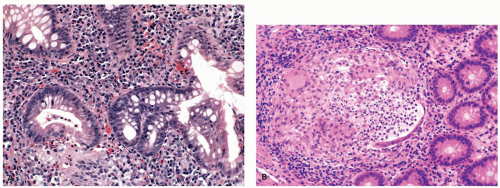

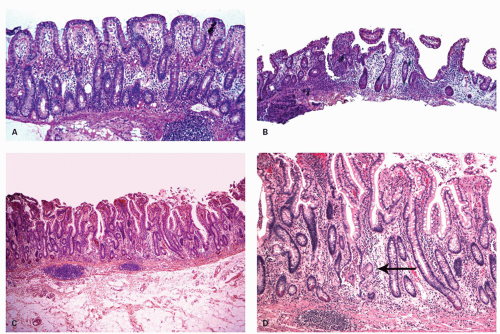

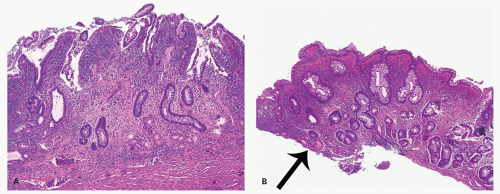

Fig. 18-14). The perpendicular orientation of crypts to each other may be lost. The distortion may result from reepithelialization of irregular crypt abscesses. Physiologic crypt division is from the crypt bases up, so they remain straight. Crypt distortion arises following erosions or ulcers when epithelium grows in from the edge of the erosion. New crypts are formed when the surface mucosa dips irregularly into the ulcer to form new crypts, but in a much more irregular manner than usual. This epithelium then develops a lamina propria and a neomuscularis mucosae superficial to the original, so that the muscularis mucosae may appear thickened (duplicated) (

Fig. 18-15A,B). Persistent mucosal architectural abnormalities are therefore characteristic of chronic UC, but transient irregularities may be observed in regenerating mucosa from many causes, even previous biopsy sites or a healing ischemic ulcer. Crypt loss may be evident as areas of mucosa devoid of any crypts. Mucosal atrophy (synonym: crypt atrophy) is a combination of crypt dropout and shortening of crypts. While ideally the crypt architecture is best assessed on well-oriented mucosal biopsies, some of the features can be appreciated even when the sections are tangential. While assessing crypt architecture one must also be aware of slight irregularity of crypts that is normally present in the rectum or in the region of the small bowel and colonic junction at the ileocecal valve.

Cryptitis: An early feature of the histology of active UC is the formation of crypt abscesses in the mucosa (

Fig. 18-14D). It must be emphasized that these reflect active disease and are not specific to UC, for they occur in a great variety of other intestinal inflammatory conditions including CD and infections. They are, however, particularly conspicuous in active UC.

277 The small microabscess thus created expands and either bursts into the lumen of the bowel, elaborating pus into the feces, or spreads into the lamina propria, or, if the inflammation is severe, into the submucosa. It is significant that neutrophils are preponderant within the lumen of the crypts in UC and, unlike infective colitis, comparatively smaller numbers are seen migrating between the epithelial cells. In acute infections, they also tend to be more superficial, but are invariably plentiful in the lamina propria. This can be a helpful feature in the differentiation of UC from infective proctocolitis. Indeed, while neutrophils can be found in the lamina propria without crypt infiltration in UC, it is sufficiently uncommon that other causes, such as CD, or an infectious colitis superimposed on UC, should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Crypt abscesses play an important role in the mechanism of mucosal ulceration and in the formation of

inflammatory polyps. In severe disease, they burst into the loose submucosal tissues; there is a tendency to spread longitudinally beneath the mucosa, which sloughs off leaving an ulcer (

Fig. 18-16). The mucosal margins of these ulcerated areas are further undermined and are relatively raised up to form polypoid tags of mucosa projecting into the lumen. These mucosal tags or inflammatory polyps can be short or extremely long and filiform.

278

Epithelial changes: The inflammatory damage to the crypts produces a variety of degenerative and regenerative changes in the crypt epithelium. There is loss of goblet cells resulting in a mucin-depleted appearance of the crypt and surface epithelium. Crypts are usually uniformly lined with many goblet cells, especially in the upper two thirds. Mucin loss may follow any acute mucosal injury, including sometimes even bowel preparation with various bowel cleansing solutions (e.g., fleet’s phophosoda) before colonoscopy. The loss of mucin following purgation or in association with inflammation can be explained by damage and loss of surface epithelial cells, and replacement of these cells by young relatively undifferentiated regenerating cells migrating toward the surface. An increased rate of epithelial cell proliferation is also reflected in the increased numbers of mitotic figures, which correlates with epithelial cell damage and regeneration. It is commonly seen in active disease, but has no diagnostic value. This should not be confused with dysplasia, where mucin depletion may also be seen due to lack of normal differentiation of neoplastic cells. In the presence of attenuated or restituting epithelium anywhere in the superficial epithelium, the changes in the crypts are almost certainly reactive. Some degree of mucin depletion is therefore not unusual in any type of colorectal inflammation although it is less common in CD compared to UC. Severe almost total mucin depletion is a characteristic and fairly consistent finding in active UC and tends to affect all crypts in the biopsy being maximal in the distal colon. The amount of mucus may reappear as disease activity subsides.

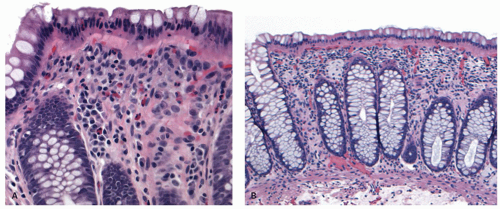

Paneth cells metaplasia is also a feature of IBD (

Fig. 18-17A).

279 Paneth cells, with the exception of the right colon and rarely in the transverse colon, are absent from the rest of the large bowel. These can be numerous in patients with long-standing colitis; however, Paneth cell metaplasia can be seen with other chronic inflammatory conditions of the bowel and are diagnostically not specific and unhelpful (

Fig. 18-17D). Increased numbers of endocrine cells may also be seen in the base of the crypts.

261 Pyloric gland metaplasia may also occur, but it is distinctly uncommon in UC compared to CD, especially in the small bowel (

Fig. 18-17B,C).

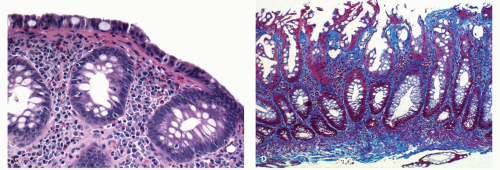

Mucin granulomas (crypt rupture or cryptolytic granulomas): A particular problem in the differential diagnosis of IBD is the giant cell reaction and poorly formed granulomas in relation to crypt damage and liberated mucin (

Fig. 18-18). These granulomas usually contain mucin and/or neutrophils, histiocytes, and occasionally giant cells.

258 However, sometimes the granuloma may also be very well formed and sarcoid like. The mucin is not always readily visible, and often the best clue is that their location is precisely in the location in which a crypt should have been, even given the irregularity that occurs in UC. Further clue is that crypt remnants may be visible although it may take levels, mucin stain and/or epithelial immunostain to demonstrate them. Such granulomas may be seen in other forms of colitis, including CD, infectious colitis, and colitis associated with diverticular disease,

280 as well as in ileal pouches.

266,

267,

281,

282 Care needs to be taken

not to say that these are “consistent with CD” on this basis alone, for once that diagnosis is suggested, it has a habit of sticking, and the patient is labeled as having “histologically proven CD.” At some point, this may deprive the patient of a pouch. In diverted UC, several types of granuloma may be seen at all sites in the bowel wall and in draining lymph nodes.

283

Lesions of the enteric nervous system are uncommon in UC and may be a good predictor of CD.

284 They are however difficult to assess on endoscopic biopsies.

285 Nevertheless in CD, involvement of the myenteric plexus by inflammation predicts earlier recurrence (see subsequent section).

Chronic inflammation: In active colitis, accompanying the changes in the crypts and surface epithelium, there is a heavy diffuse infiltrate of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria. These include neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and mast cells. Studies of immunoglobulin-containing

plasma cells in UC demonstrate an increase in the major forms of IgA, IgG, and IgM.

286 The increase correlates with disease activity and the rise of IgG- and IgM-containing cells is proportionally more than for IgA-containing cells.

287

Eosinophils and Mast cells: In some biopsies from UC, large numbers of eosinophils may be seen in the lamina propria, and may completely dominate the inflammatory infiltrate. This infiltrate has been the subject of much study in attempts to correlate it with clinical outcome, but there have been no consistent results.

287 It likely reflects the extreme end of the Th2 response that is said to characterize UC. Further, in developed countries quiescent UC is by far the most common cause of “eosinophilic colitis.” This is further discussed in the section on eosinophilic colitis. The same conclusion has to be made about mast cell numbers,

287,

288,

289 although difficulties in techniques for demonstrating degranulated mast cells complicate the issue if histochemistry rather than immunohistochemistry is used.

Basal lymphoid follicles/aggregates: In long-standing disease, hyperplasia of mucosal basal lymphoid follicles becomes a prominent feature, particularly in the rectum (follicular proctitis), but in resections, transmural inflammation in the form of lymphoid aggregates and hyperplasia, characteristic of CD, is never seen in UC, although it is a feature of the diverted rectum in UC.

283 Vasculitic lesions of polyarteritis type in submucosal vessels are only seen rarely in UC.

290 Inflammation within blood vessels may be seen close to ulcerated areas, but this is usually a secondary feature. Granulomatous vasculitis, which is sometimes seen with CD,

291 has only been described in UC in association with diversion.

292 Assessment of disease activity in IBD and “Deep Remission”: Assessing disease activity is an evolving area with wide variations in current practice. The primary goal of treatment in IBD has always been control of symptoms. However, with newer therapies, endoscopic remission has also become an additional end point of therapy, and histologic remission is gaining importance, especially in UC. The combination of all three parameters of remission is suggested to be “deep remission” and is the ideal aim of therapy. Although most patients do show overall histologic improvement following clinical remission, histologic correlation with symptoms and endoscopic findings is modest.

293 Some patients in clinical remission continue to show dense lamina propria lymphoplasmacytosis and sometimes persistent acute inflammation, while others continue to have symptoms despite a decrease in inflammation. In some patients, persistent symptoms relate to concomitant IBS or functional, noninflammatory-related complaints.

Studies suggest that active inflammation (neutrophilic infiltrate) not only correlates with clinical disease and endoscopic severity but, along with basal plasmacytosis, predicts disease relapse as well.

293 Thus, patients with basal plasmacytic infiltrates (as in

Fig. 18-14B,C) are more likely to relapse than those without it (as in

Fig. 18-19). Indeed, if chronic inflammation can be kept within normal limits, relapse is unlikely. The real purpose of therapy is therefore not just to get the patients into remission but to keep them there. This implies that it would be wise to continue maintenance therapy (e.g., mesalamine) in patients who fail to achieve “histologic remission.” Conversely if the patient is being treated with steroids, one might be reticent to prolong or increase therapy simply to produce histologic remission (i.e., a normal lamina propria), and the notion of upgrading therapy, for example, by adding steroids, cannot currently be justified. Well-designed clinical trials in appropriate patient populations are required for this to become

the standard of practice and care. However, the paradigm shift toward getting a patient into a remission that is clinical, endoscopic, and histologic (no acute inflammation and a normal chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria) is increasingly being considered as ideal.

293Histologic grading and reporting of UC/IBD biopsies: The issue then becomes how one should report these biopsies, what features should be mentioned (active vs. chronic changes), and what grading system to use. Most pathologists tend to grade the acute (active) inflammation subjectively into none (quiescent), mild, moderate, and severely active ulcerative colitis, with or without specific mention of the chronic inflammation. While this system is simple and practical, there are no specific reference criteria, so this is entirely subjective. Although more objective histologic scoring systems of disease activity in IBD have been developed, their utility has been largely limited to clinical trials and research. Truelove, in Oxford, devised the first recorded method relating symptoms to the amount of neutrophilic infiltrate and epithelial damage. Subsequently, the Riley system, which is similarly based, was designed and showed that a mild activity score (occasional small groups of neutrophils in the lamina propria) correlated with early relapse after cessation of treatment.

293 The Geboes system is easy to use and has been tested for its reproducibility

293 (

Table 18-6).

However, for clinical practice, these systems are a bit complex and difficult to apply. Many pathologists simply report these biopsies as “mild, moderate, or severe ulcerative colitis”, with no reference to chronic features with the argument that this is already implicit in the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. There is certainly merit in grading acute/active inflammation in symptomatic or endoscopically active patients, as these provide a good indication of disease severity. However, as the concept of “deep remission” becomes increasingly important, grading of chronic inflammatory features in addition, especially if basal plasmacytosis is present, also becomes important, especially in patients with few or no symptoms and lesser endoscopic activity, as it predicts an increased risk of relapse.

A simplified but comprehensive grading system is shown in

Table 18-7A, in which both the acute and chronic components are graded separately. The system can be used for any form of IBD, which is helpful as often the nature of underlying chronic colitis remains unclear for a variety of reasons. Ulcerative colitis can be reported as, for example, “moderate chronic ulcerative colitis, with mild activity” or simply “mildly active moderate chronic ulcerative colitis,” or “mild chronic active ulcerative colitis.” One could replace ulcerative colitis with simply “chronic colitis,” and the system can be used for any form of IBD. The system is particularly useful as it can be used at the time of initial diagnosis as well as during any follow-up biopsies and can be used for any form of IBD. If there is no active or chronic inflammation but yet there are changes of architectural distortion or Paneth cell metaplasia, this can be reported as “quiescent

colitis.” Features like architectural distortion and Paneth cell/pyloric metaplasia have poor correlation with clinical disease, and their only value in reporting is to establish the presence of the underlying disease. The absence of any chronic changes or presence of minimal changes could imply complete histologic remission or even raise a doubt regarding the diagnosis of IBD. Sometimes during a follow-up biopsy, the clinicians may want to know if in fact ulcerative colitis is truly the correct underlying diagnosis, so “features of active colitis are absent, but crypt architecture changes as seen in inactive/quiescent ulcerative colitis” can be helpful. Alternatively, a sign out of “there are no features of active colitis or chronic changes” or that that the “biopsy is normal” can also be helpful. However, it must always be remembered that architecture can return completely to normal, so the absence of architectural changes never excludes the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. Thus, “there is no evidence of IBD in these biopsies” works better than “normal biopsies” for that reason. One should recognize that the importance of routine, repeated biopsy examination in IBD is not just to assess disease activity, but sometimes to confirm the diagnosis or to raise the question of other forms of IBD, to exclude concurrent infection (especially those in which organisms may be visible), and to assess for the presence of dysplasia or carcinoma.

Simple grading system for ulcerative colitis: This is based on the assumption that there is virtually never any acute inflammation (at least caused by IBD) without chronic inflammation also being present, so the paradigm of “no chronic inflammation—no acute inflammation” holds in IBD. No acute inflammation obviously implies that there is no cryptitis, crypt abscesses, erosions, or ulcers. Then logically if there is acute inflammation, it can be graded subjectively, but that in the presence of acute inflammation, grading chronic inflammation is unnecessary as it is always present to some degree, and is of no clinical significance as the presence of any acute inflammation implies an increased risk of relapse.

If there is no acute inflammation, it is only worth grading chronic inflammation as normal (rarely decreased post therapy) or increased and if increased with or without basal plasmacytosis, the latter predisposing to relapse in patients with quiescent disease.

293 A system for both grading biopsies and predicting relapse based on both the Geboes and Bessissow criteria is shown in

Table 18-7B. However, one needs to be careful while dealing with biopsies from the right colon (cecum, ascending colon) that can have basal plasma cells normally, especially in adults. Biopsies from this region should therefore always be considered normal if based on chronic inflammation alone. As this tends to be an age-associated change, basal plasma cells may be more important in children in this location.

Various examples of biopsies with UC

Biopsies from the cecum and ascending colon—colonic mucosa without abnormality

Biopsies of large bowel from transverse colon—architectural distortion as seen in quiescent ulcerative colitis

Biopsies of the descending colon—ulcerative colitis with an excess of chronic inflammatory cells but without basal plasmacytosis

Biopsies from the sigmoid colon—chronic ulcerative colitis with moderate basal plasmacytosis*

Biopsies from the rectum with mildly active ulcerative colitis* |

* In patients in clinical remission, the presence of these features has been reported to increase the likelihood of clinical relapse. |

Bessissow T, et al. Prognostic value of serologic and histologic markers on clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis patients with mucosal healing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1684-1692. |

This is far from perfect and does not answer questions such as how many basal plasma cells are required (more than the odd one), or how many neutrophils are required to change from one grade to another, or the significance of numerous eosinophils. However, it does provide a relatively easy-to-use system that does have clinical relevance and is semiquantitative.

RESOLVING COLITIS. The relapses and remissions of UC imply that inflammation may resolve spontaneously. Evidence that this is the case comes from numerous placebo-controlled studies when up to about a third of patients in any placebo group go into remission spontaneously. Hence in clinical trials, drugs need to demonstrate a correspondingly higher response rate to be considered beneficial. Furthermore, resolution can occur at different rates in different anatomical areas of the colon. This can give a false impression of segmental disease, not only macroscopically but also microscopically.

270,

272,

295 With resolution of disease, the numbers of inflammatory cells of all types begin to diminish and their distribution becomes uneven. The goblet cell population returns toward normal and, depending on the severity of the attack, the crypt architectural changes may persist. Some crypts may appear short; others branched, the changes invariably being more marked distally.

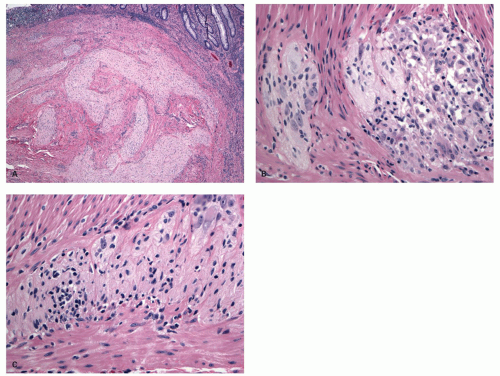

QUIESCENT COLITIS. Varying degrees of crypt atrophy and distortion are the hallmarks of quiescent disease. Shortfall of the crypt with regard to the muscularis mucosae and crypt loss are convenient ways of assessing this atrophy when present, and the lamina propria may show an unusual “empty” appearance (

Fig. 18-19). On the other hand, there may be lymphoid hyperplasia (follicular proctitis) in the rectum (

Fig. 18-20). Crypts are normally present in the large bowel mucosa at a frequency of six per millimeter in a biopsy, which includes muscularis mucosae. In a biopsy without muscularis mucosae, the mucosa may be stretched out and appear atrophic when it is not. Edema may also mimic crypt atrophy due to separation of crypts; this may follow administration of bowel preparation fluids, especially older hyperosmolar solutions.

296 Inflammatory polyps can be seen in a background of quiescent colitis. Sometimes, thickening of the muscularis mucosae is also seen, and may

be the only evidence of past inflammation or ulceration (

Fig. 18-19B).

297

While most patients have some residual changes of previous damage (crypt distortion, atrophy, Paneth cell metaplasia), it has become increasingly recognized that a group of UC patients may show complete resolution with no evidence of previous disease.

271,

272,

295 This always raises the question as to whether the original diagnosis was really UC or an infective (self-limited) colitis and a careful review of all clinical data and histologic material may be warranted. After such review, there remains a patient group with genuine UC, with collateral evidence for such a diagnosis, including coexistent PSC, who undoubtedly show evidence of complete mucosal recovery, although the colitis of PSC may tend to be more right-sided than usually seen in UC.

298The condition of the patient group with histologic evidence of UC with crypt architectural distortion but with normal radiology and colonoscopy has been termed “minimal change colitis.”

12 This is not a great term, and “quiescent ulcerative colitis” is much less ambiguous. It should not be confused with microscopic colitis, since there is crypt architectural distortion, which is not a feature of microscopic colitis. Minimal change colitis may be seen after treatment or at presentation, and indeed may never develop endoscopically recognizable changes, although some authors claim that minor vascular abnormalities may be seen at colonoscopy. It is not clear why some patients show quite florid atrophy, yet in others the mucosa returns to a state close to normality.

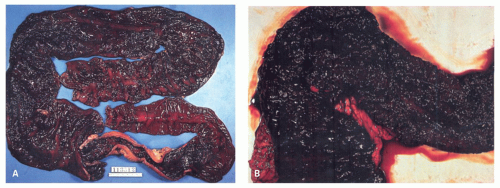

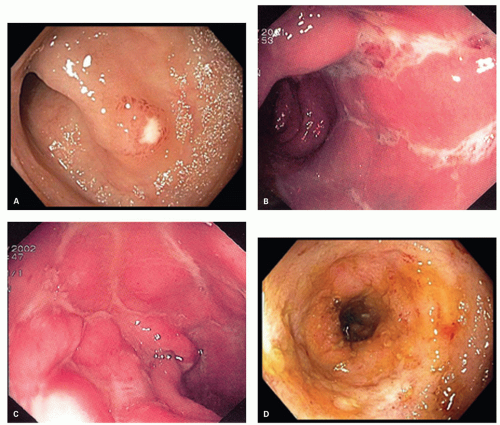

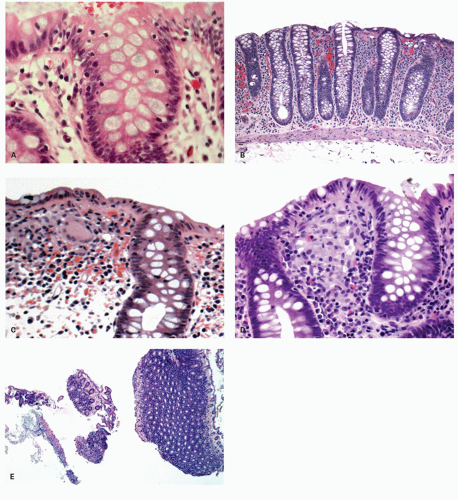

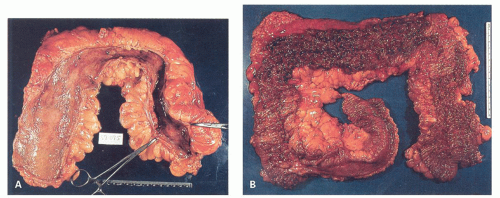

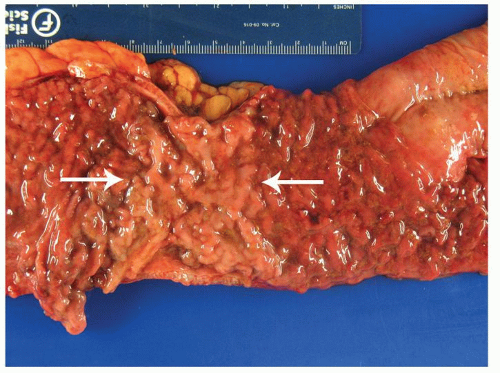

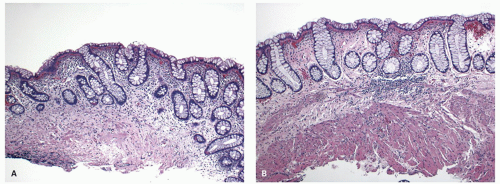

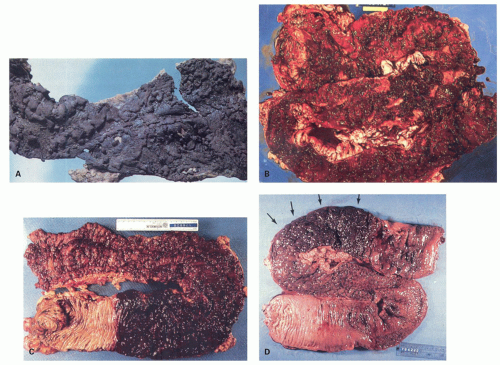

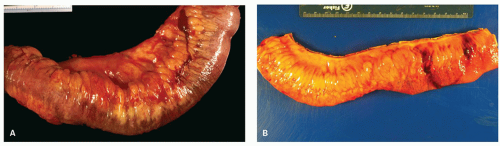

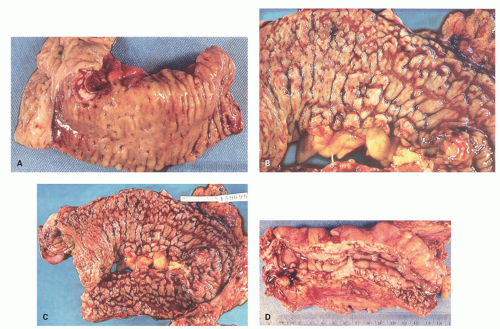

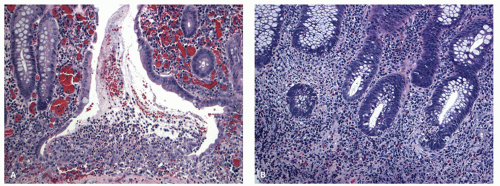

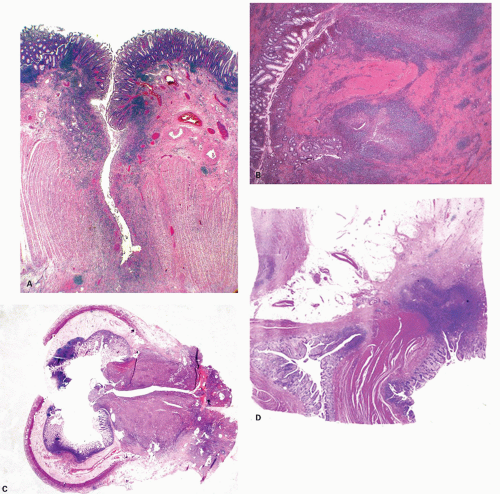

POLYPS IN ULCERATIVE COLITIS. Polyps in UC are common, being present in 12% to 20% of cases and more commonly associated with bouts of previous severe disease.

299,

300 These represent both mucosal excrescences

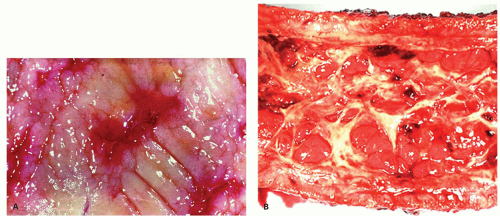

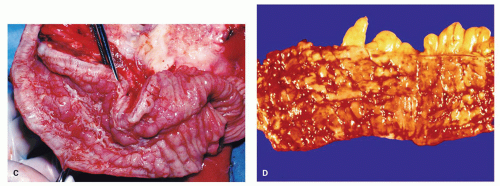

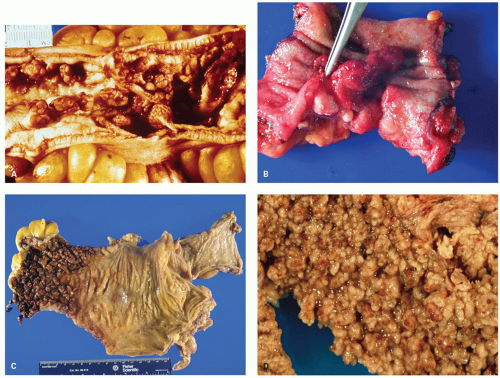

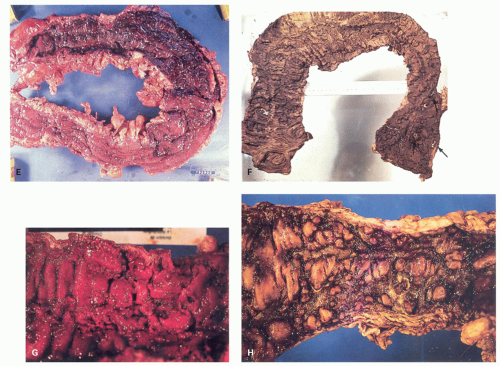

and sometimes reepithelialized granulation tissue. These inflammatory polyps or mucosal tags may be present in large numbers and adopt bizarre shapes (

Fig. 18-21A-D). The pathogenesis involves previous severe ulceration: islands of preserved inflamed and edematous mucosa that eventually take the shape of polyps and over time reepithelialization of the intervening ulcers (

Fig. 18-22A-D).

278,

301 The term “pseudopolyp” has been used to describe these postinflammatory polyps, but this appears to be a poor term. First, there is certainly nothing “pseudo” about these polyps, while “inflammatory polyp” is a better expression as it indicates the way in which the polyps are formed, and it satisfies the definition of polyp handsomely. However, they have to be distinguished from residual mucosal islands—which may be genuine “pseudopolyps.” These are the result of localized ulceration of the mucosa and usually submucosa, with undermining of adjacent intact mucosa. The surviving mucosa appears raised, but only relative to the adjacent ulcerated mucosa, so that it appears to form a polyp, which is really a mucosal island, and therefore appears to project into the lumen. The term mucosal island is better than pseudopolyp, removing the ambiguity inherent in that term.

Inflammatory polyps do not correlate with the disease activity, but indicate severe disease, usually in the past. The polyps can be found anywhere in the colon, or elsewhere in the bowel were there has been ulceration. Inflammatory polyps can adhere to one another to form mucosal bridges across the lumen (

Fig. 18-11). If healing takes place, forests of polyps may remain as evidence of past disease, so-called colitis polyposa (

Figs. 18-21A,C,D and

18-22D). The polyposis of UC tends to be more prominent in the colon than the rectum and may be seen proximal to the area of active disease. Even when few or isolated, polyps are less frequent in the rectum, and more common in the sigmoid and descending colon. Inflammatory polyps can occur in both major types of IBD, but are

much commoner in UC.

301 They can also be found guarding the entrances and exits (and within) fistula tracts, so are sometimes called sentinel polyps. While confusion can occur grossly with adenomatous polyposis syndromes on gross examination, the appropriate histologic diagnosis should be sought by examining the background mucosa.

The distribution of polyps depends on the extent of the primary disorder. They are typically small (measuring <1.5 cm in height), often multiple and may resemble adenomatous polyps grossly. Inflammatory polyps (especially large ones) may produce acute obstruction or intussusception, or may mimic carcinomas. Arborization is a striking feature in some. Feces tend to become trapped within the maze of mucosal fronds and this can cause local inflammation.

Rarely, the inflammatory polyps may have a filiform configuration characterized by thin and long polyps that resemble worms or spaghetti (

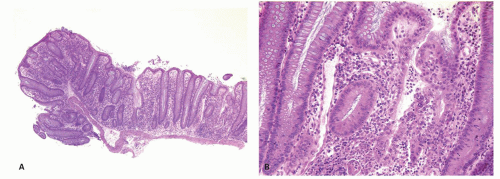

Fig. 18-23A,B).

302,

303 Filiform polyps may be as long as 2 to 3 cm. The filiform polyposis is often segmental or focal, and frequently spares the rectum. It may sometimes completely fill the colonic lumen producing obstructive symptoms. Ulceration is conspicuous by its absence on macroscopic inspection and adjacent flat mucosa can appear quite normal grossly. Filiform polyposis, usually coexists with chronic IBD, although some patients apparently have no evidence of IBD.

287,

288,

304,

305 However,

unless these are a form of hamartomatous polyposis, they must have been preceded by severe ulcerative inflammation, even if its etiology is obscure.

Benign inflammatory polyps rarely become dysplastic, but this does occur. The main problem with these polyps when numerous is that it is virtually impossible to carry out surveillance so that their presence inevitably leads to serious consideration of colectomy. Adenomas can also occur in UC as in the rest of the population, as do IBD-associated dysplasia and are discussed later in the section on dysplasia in IBD.

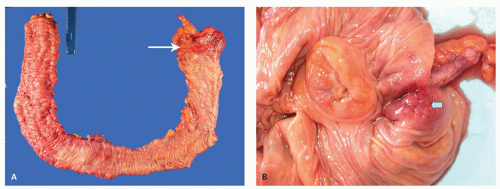

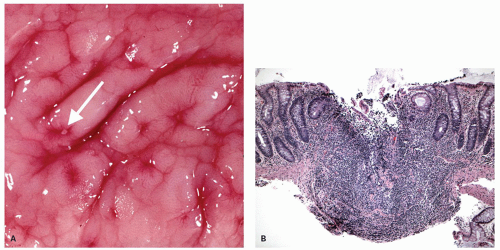

Focality/patchiness in ulcerative colitis. UC is classically diffuse in its distribution. However, not all the diseased bowel need be in a similar state of activity and this can create a false impression of segmental involvement. Activity is usually maximal in the rectum unless the patient is receiving local therapy, and tends to decrease proximally, although occasionally the colitis associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis may have an appearance of right sided ulcerative colitis (see subsequently). An isolated patch of inflamed mucosa can be seen in the cecum (cecal patch—

Fig. 18-24A) or around the appendiceal ostia (periappendiceal patch—

Fig. 18-24C) as a discontinuous lesion in patients with left-sided or distal UC (

Fig. 18-24A,B).

306,

307,

308,

309,

310,

311,

312 The histologic changes in these discontinuous cecal or periappendiceal patches are no different from typical IBD. Periappendiceal or cecal patches should not occur in patients with pancolitis, being part of the background disease, but while this can occur they are often found as isolated changes in patients with distal colitis—usually but nor always ulcerative colitis. The reported incidence of appendiceal involvement (21%-86%) and cecal patch (10%-75%) is highly variable, and occasionally, similar

skip lesions in the ascending colon have also been described in a small subset (4%). One study found that periappendiceal disease had a male predominance, and none had a prior appendectomy.

313 The other situation of segmental or patchy inflammation is presentation as diverticular-associated colitis, described subsequently.

Focality of inflammatory activity can also be induced by treatment, especially local steroid enema in the rectum or occasionally following spontaneous remission

295 (see later). During remission the mucosa may become normal again. Healing often occurs in an irregular discontinuous way, but often occurs first in the rectum.

314 Treatment may increase the heterogeneous nature of the lesions. Topical treatment of the rectum with steroid or 5-ASA enemas may induce complete rectal healing while the lesions in the other segments of the colon may persist.

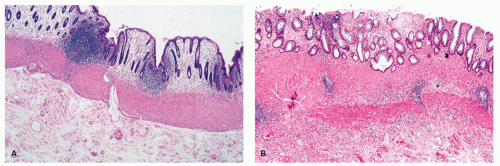

270Appendiceal involvement. The role of the appendix in the possible etiology of UC is discussed previously. The appendix is involved in about 75% of total colectomy specimens performed for UC. This may be continuous or as a skip lesion.

309,

310,

311,

312 Such a “skip lesion,” although apparently suggestive of CD, should not be regarded as a contraindication to pouch surgery. The appendicitis may extend into the contiguous large bowel as a periappendiceal patch, and does not lead to acute suppurative appendicitis because the inflammation remains confined to the mucosa.

307 When symptoms occur, they are more likely to be the central abdominal pain, and very likely to be interpreted as the mild pain associated with the active colitis rather than due to acute appendicitis. The pathologic features are identical to the mucosal changes seen in the rest of the colon (

Fig. 18-25A,B). The practical question is what should one do when one sees changes suggestive of UC in an appendectomy specimen in a patient with no preceding history of IBD. It is recognized that some patients with IBD (more often CD) will initially present with appendicitis and some will develop it years later. Most often, the changes of IBD are either masked by features of acute appendicitis or absent, while on occasions, the mucosal changes overwhelmingly mimic IBD with significant crypt distortion and minimal transmural acute inflammation. Our approach is to note these changes in the report and ask the clinician to exclude any concomitant evidence of IBD by colonoscopy and keep an eye on for future development of IBD.

Rectal sparing. UC with an endoscopically and histologically normal rectum probably occurs only rarely.

315 Occasionally, the rectal mucosa may look endoscopically normal, but show inflammatory changes on histology, hence the importance of biopsying the rectum during the initial evaluation of IBD cannot be overemphasized. Some of the older literature on rectal sparing in UC was entirely based on endoscopic evaluation only, and hence cannot be relied upon. The rectal sparing can be produced by healing in response to local steroid enemas, sometimes leading to endoscopic, but not histologic healing. In most patients architectural distortion is present, but, as discussed previously, this can also completely resolve. Even when the mucosal histology returns to normal, thickening and duplication of the muscularis mucosae and a degree of submucosal fibrosis are invariably present, but these can only be evaluated properly on resection specimens.

316 It is best termed

relative rectal sparing rather than true rectal sparing. On occasion, relative rectal sparing may occur in some patients with UC in the absence of rectal instillation of anti-inflammatory drugs. However, in two controlled studies of UC with apparently normal

rectal mucosa, associated with PSC, while one study showed a distinct right-sided tendency of the persistent inflammation,

298 the other failed to show any difference from controls.

317 There is no way of knowing whether the rectum was ever involved in these patients or this represented spontaneous resolution of inflammation.

318 Relative rectal sparing has also been documented in children more frequently (see later).

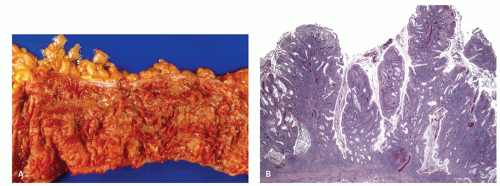

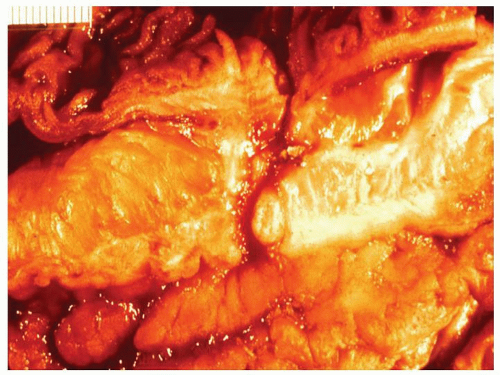

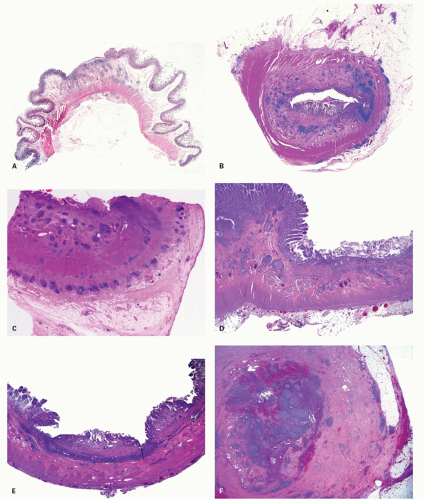

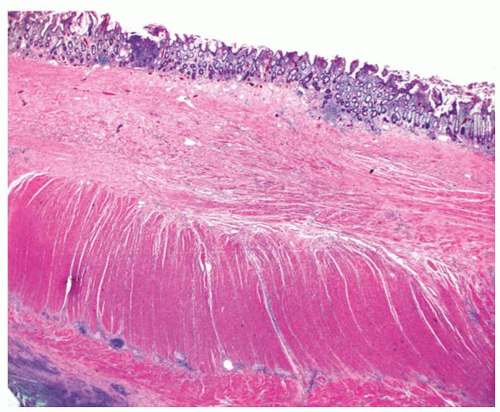

Ileal involvement in ulcerative colitis. When the terminal ileum is involved, the mucosal changes are similar to those seen in the colon, and are always in continuity with disease in the large bowel, being associated with an open dilated and incompetent ileocecal valve. Although the expression “backwash ileitis” is not necessarily accurate, because there is, as yet, no evidence that ileal disease is the result of such a mechanism, it is in common usage. However, the term is clinically useful as it differentiates ileitis associated with UC from other causes. Ileitis is found in about 17% of colectomy specimens for UC, the extent of involvement varying from 5 to 25 cm, but rarely is considerably longer (up to 50 cm; see also

Fig. 18-29A), although in most resections, the true length is difficult to evaluate as routinely very small cuff of terminal ileum is removed close to the ileocecal valve.

319,

320,

321 The histologic changes are generally mild with mild crypt architectural distortion, mild villous blunting, and increase in lamina propria inflammatory infiltrate (

Fig. 18-26A,B). Superficial erosions, cryptitis, and crypt abscess can also be seen. Although pseudopyloric metaplasia can be occasionally seen, the presence of granulomas or transmural inflammation should raise a concern for CD. While most of the cases are associated with pan-colitis, in one study, few patients had only extensive or left-sided colitis. The degree of inflammation in the ileum generally parallels the degree of inflammation in the cecum. In biopsies, the key is that the disease has to be at least as severe in the biopsy/biopsies immediately distal to the ileo-cecal valve. If that is not the case, then it is reasonable to exclude backwash ileitis and consider the other major causes of ileal inflammation, NSAIDs/ASA or CD. It is unclear if a cecal patch can have an associated

ileitis, but there are no good data on which to make that assessment. However we have seen ileal biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis with occasional foci of acute inflammation in the lamina propria, but are unsure of its significance.

Pan enteritis post colectomy for ulcerative colitis. This is a rare condition in which patients who have either undergone subtotal colectomy for UC, or had an ileo-anal pouch formed in addition, present with severe inflammation that involves the entirety of the small bowel (Fig. ), pouch and can also involve the stomach (it may not be in continuity). The presence of an ileal pouch seems often to be key. The features present in the initial resection are characteristic of UC. The subsequent presentation of panenteritis with histologic features of IBD, coupled with the clinical unresponsiveness to antibiotic treatment and histologic absence of CMV, suggests the diagnosis of UC-associated enteritis.

In the small bowel, the more common histologic finding is diffuse superficial chronic active enteritis, essentially similar to UC in the large bowel. Indeed the initial impression is of a flat mucosa with all of the features of UC except that the biopsies are from the small bowel. In addition, Lin et al. noted that of 4 cases of diffuse duodenitis occurring in UC, all occurred in patients with pouchitis.

321a Valdez et al. also noted the presence of duodenitis in UC: 3 of 4 had duodenitis following a pouch procedure, and 1 had duodenitis preceding colectomy.

321b Similarly, Wang et al. noted that while duodenal inflammation could occur in UC in the absence of pouchitis, crypt architectural changes only occurred in patients with pouchitis.

321c This association of duodenitis with pouchitis may represent proximal and distal sampling, respectively, of a diffuse panenteritis following colectomy. More recently, small intestinal lesions consisting of ulcers and edema were observed by capsule endoscopy in patients with UC following proctocolectomy, though interestingly these features were also observed in active UC prior to surgery.

321d Treatment is that for IBD with high-doses of corticosteroids with or without azathioprine, and once in remission patients don’t seem to relapse.

321ePrestomal ileitis. This can occur following colectomy and ileostomy, and is probably a complication of the ileostomy operation.

322 In this rare complication, ulcers are scattered throughout the ileum and jejunum. The intervening mucosa may be abnormal and in continuity with the ileostomy, when possible ischemia may be considered. When there is normal intervening mucosa the possibility of CD inevitably gets raised, but there are no good data regarding this. If the lesions are ever resected then usual criteria for possible Crohn’s, and other diseases can be applied. The ulcers can perforate, resulting in peritonitis and fecal fistulae. Inflammation of the ileum also occurs in pelvic ileal reservoirs (pouchitis) with an adaptive change in the mucosa (“colonic metaplasia”) to produce a picture similar to the original colitis, and in the ileum proximal to the pouch (prepouch ileitis). Prepouch ileitis is uncommon; however, it may extend for long distance (upto 50 cm) in some patients.

319 In one study of 571 patients of UC who underwent restorative proctocolectomy, 19 (3%) developed prepouch ileitis, of which 3 were reclassified as CD.

319 Only 7(47%) of these had associated pouchitis and only 2 had preoperative backwash ileitis. The histologic changes tend to be similar to pouchitis.

319 These changes are discussed further in the section on pouchitis.

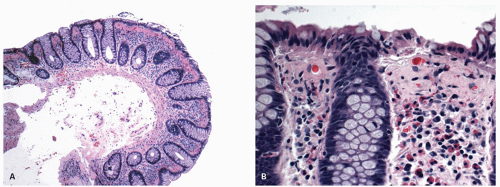

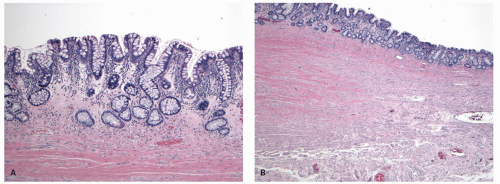

Ulcerative colitis in children. Colonic mucosal biopsies from children presenting with new-onset UC can show significantly less histologic abnormalities across all pathologic parameters routinely used in the evaluation of chronic colitis. Rectal sparing has been well documented at the initial onset.

315 In samples from children between 1 and 10 years of age, significantly less crypt branching, plasma cells in the lamina propria, cryptitis, crypt abscesses, and epithelial injury are present when compared to adults (

Fig. 18-27A,B). Focal colitis and/or absence of chronic crypt abnormalities are observed in initial rectosigmoid specimens in approximately 33% of patients. In 4% to 8% of cases the initial biopsy samples are completely normal. In children older than 10 years, the histologic changes tend to be similar to adults.

323 These differences can probably be explained by the duration of the disease, which is likely to be longer in older children.

Proctitis/ulcerative proctitis. Localized inflammation of the rectal mucosa can be caused by a great variety of circumstances such as mucosal prolapse, trauma, suppositories, radiation, antibiotic therapy, piles, persistent diarrhea, CD, UC, and, in more recent years, increasing numbers of infectious agents, the latter having particular importance in the homosexual population, as well as in women engaging in anal sex (

Table 18-8). The old viewpoint was that when these causes have been excluded, one is left with an idiopathic pattern of distal disease

324 for which there were many synonyms, including proctosigmoiditis, idiopathic proctitis, nonspecific proctitis, lymphoid follicular proctitis, and ulcerative proctitis. This implied that “nonspecific ulcerative proctitis” is a disease of exclusion. Up to a point that is correct if only clinical features are used and infections are excluded. However, on biopsies, the changes of UC are really quite characteristic and, like its more proximal

counterpart ulcerative proctocolitis, the changes are usually readily discernable on biopsy. The “nonspecific” part of this designation is therefore an historical title borne out of ignorance when all biopsies were called “nonspecific chronic active colitis/proctitis” (regrettably still all too common). There was no appreciation that the chronic infections of this region whether venereal, tuberculous, or even amebic could be diagnosed and treated. Now we recognize that a vast majority of chronic proctitis encountered in clinical practice in Westernized societies represents IBD (UC/proctitis) and crypt architectural distortion, deep lamina propria plasma cells, cryptitis, and crypt abscesses are characteristic histologic changes. The other main form of IBD, CD, rarely presents as proctitis alone. However, it should also be recognized that the changes are not entirely specific, and as listed in the table other causes need to be considered in the differential diagnosis. Some of the chronic infections at times very closely mimic IBD and require a detailed clinicopathologic workup including demonstration of the pathogen in the tissues. Rarely, the changes of ulcerative proctitis can be those of a follicular proctitis.

The precise extent of the disease should be determined by flexible sigmoidoscopy and biopsy, for it is found that endoscopically normal mucosa may be histologically inflamed.

325 Biopsies above the proximal limit of disease may reveal that the disease is much more extensive than grossly evident. This is important to document as this finding may mark the patient for surveillance colonoscopies in the future. Hence, a case should not be signed out as ulcerative proctitis if biopsies are only available from the rectum. This is also the case when biopsies are available from the rectum and an area much more proximal such as the transverse colon, but excluding sigmoid and left colon. Such cases should be signed out as having changes limited to the rectum, but the differentiation between ulcerative proctitis and UC cannot be made in the absence of sigmoid and other more proximal biopsies.

In addition, approximately 10% of patients with ulcerative proctitis will develop more extensive ulcerative proctocolitis,

326 whereas 15% will have recurrent bouts of active disease and 75% will enter permanent remission. Extension of disease usually occurs within 2 years and seldom after 5 years.

324 There is some evidence that distal disease may predominate in the elderly population.

327 The symptoms from severe proctitis may be disabling as a result of defecatory

frequency and urgency with blood but little or no diarrhea. In addition, chronic ulcerative proctitis may sometimes be remarkably resistant to medical therapy, including 5-aminosalicylic acid, local and even systemic steroids, or immunosuppressive agents. Some patients with only rectal involvement benefit greatly from restorative proctocolectomy.

328 Morphologically, it has the features of UC, although the chronic inflammatory component may be more severe than those with more extensive disease even in remission.

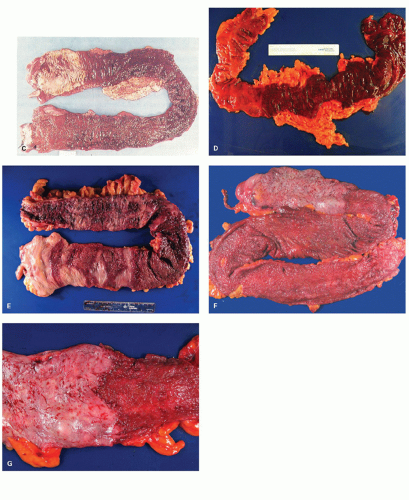

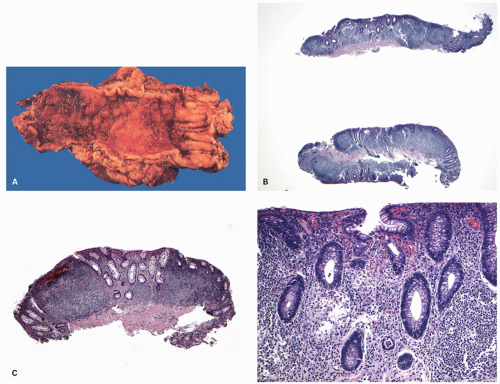

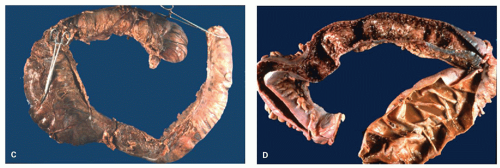

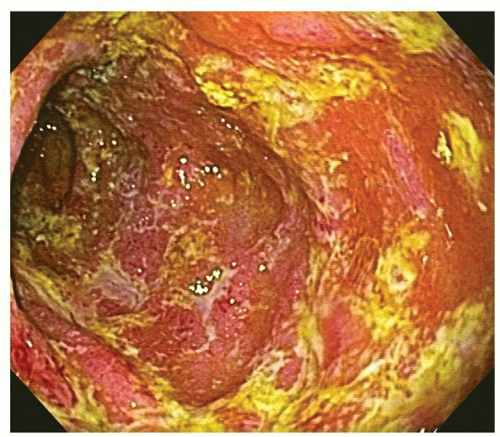

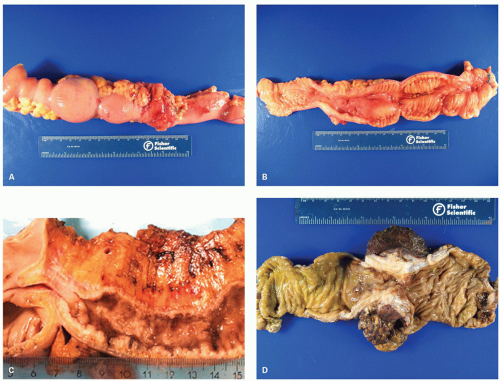

277Fulminant colitis and toxic megacolon. Fulminant colitis is a severe disease and can complicate any form of colitis, including IBD and infections, and in a proportion, the colon may have to be resected as an emergency measure (

Figs. 18-28 and

18-29). The clinical criteria are listed in

Table 18-9. In some, the etiology remains uncertain forever. About 5% to 13% of all patients with UC have an episode of fulminant colitis

330,

331, either as a first attack or during an acute relapse. Sometimes a segment, of the bowel, most commonly the transverse colon becomes acutely dilated resulting in so-called toxic megacolon, and the bowel wall is consequently markedly thinned (

Fig. 18-29C,D). Single or multiple perforations of the thinned bowel, either spontaneous or produced at the time of operation, were at one time common, but these days no colitic should be allowed to reach this state, and perforation is rare. Perhaps, the most important feature of these diseases is to appreciate that fulminant colitis of any cause can be accompanied by transmural inflammation and by fissuring ulcers. The presence of these does not indicate that the underlying disease is CD.

Gross Appearances There is frequently a fibrinous or fibrinopurulent exudate on the peritoneal surface, and rarely overt perforation may be seen—not necessarily in the presence of toxic dilatation, but just severe disease. The cecum and ascending colon are

not invariably involved.

332 There may be proximal or distal sparing, or both, even in cases of UC and can be misleading.

316,

333 Further, the transition may be in the form of aphthoid ulcers. The inflammation can be focal or diffuse, the mucosa can be either diffusely hemorrhagic or there may be linear ulcers. The intestine may have the consistency of wet paper, tearing readily with subsequent peritonitis. Extensive loss of mucosa can occur and any surviving mucosa shows intense vascular congestion and edema, although sometimes with a relatively mild inflammatory cell response. In areas of mucosal ulceration, the submucosal tissues largely disappear laying bare the deep muscle coats, which may be covered by only a thin layer of very vascular granulation tissue, and may also be visible grossly.

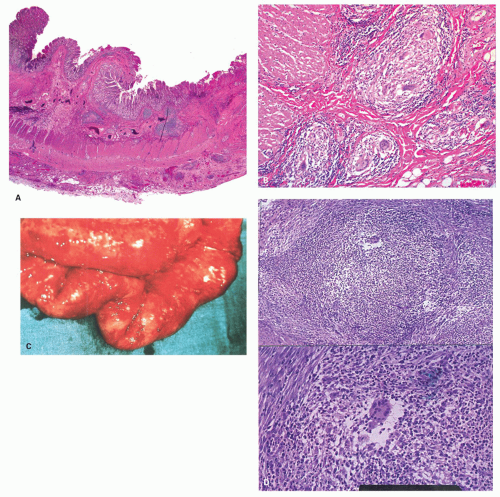

Depth and Type of Inflammation In fulminant UC, there is inflammation beyond the mucosa, often into, and sometimes through the muscularis propria, unlike that usually seen in UC (

Fig. 18-30). However, the pattern of this inflammation is important. In fulminant UC, the active inflammation extends into the muscularis propria as a polymorphous infiltrate. This is quite different from the focal lymphoid hyperplasia with lymphoid aggregates and follicles, which are seen in a transmural distribution in CD. Granulomas are rare, but care has to be taken with mucosal granulomas that are much more frequently secondary to ruptured crypts or foreign material. The myenteric plexus may be incidentally involved, but the colonic dilatation might be due to a primary toxic atrophy of muscle cells,

331,

334 although sometimes, dilated capillaries seem to be the cause of the myocytolysis (

Fig. 18-30).

In toxic megacolon, the inflammation extends deeper and the bowel wall is usually very thin. Frequently, one sees peritonitis as well as fibrinous or fibrinopurulent exudates on the peritoneal surfaces. Edema widely separates the fibers of the muscularis propria, leading to incipient perforation. The frequency of perforation in megacolon historically was seen up to 40% patients, but now is rare, but can also be seen occasionally in patients without megacolon. However, the term megacolon is dependent on radiological measurements of bowel diameter, which is unreliable as there is usually no control and normal varies hugely.

Fissuring ulcers are part of severe or fulminant disease irrespective of the underlying etiology, and do not imply CD (

Fig. 18-30E). These may go into and sometimes through the muscularis propria, but perforation is rare. However, transmural inflammation is polymorphous and plasma cells, eosinophils, macrophages, mast cells, and lymphocytes are all invariably present. The diagnosis of CD requires as a minimum transmural lymphoid aggregates (not just one—see below), or granulomas away from areas of active inflammation so that foreign material including mucin can be excluded.

Residual mucosa is worthy of careful evaluation. While all have an excess of chronic inflammation with deep plasma cells to indicate the underlying chronic

colitis, some have overt diffuse architectural changes indicative of prior UC (

Fig. 18-30B). These can be signed out as severe active UC. Where it is focal, the possibility of CD needs to be considered, but still requires the features described above.

However a third group of patients have virtually no architectural abnormality. Most of these present with a first attack of severe disease that is unresponsive to most therapies, may be held in check briefly with TNF-a antagonists, but ultimately undergo colectomy. The lack of architectural changes may cause the diagnosis of UC to (reasonably) be questioned, although chronic inflammation with a basal plasmacytosis may be present, representing disease that has been present for more than a couple of weeks (the time it takes to mount a good B-cell response). The key features here are that while polymorphous transmural inflammation and fissuring ulcers may be present, there are no other mucosal features to indicate that the underlying disease is UC. Neither are there features to indicate CD, whether transmural lymphoid hyperplasia or granulomas not attributable to mucin or foreign material and ideally away from fissures or ulceration and along the subserosa. They may represent IBD or severe undiagnosed infection, but their etiology remains unknown. The problem is in knowing what to call them. While indeterminate colitis/colitis indeterminate is one way out, this term has been used in so many contexts that it is highly ambiguous (see subsequent discussion regarding indeterminate colitis). A third possibility is to call them severe colitis of uncertain pathology. Whichever term is used, it is useful to state that there are no features to indicate CD, and therefore to preclude ileoanal anastomosis, but may be at the usual risk of pouchitis.

It should also be appreciated that fulminant colitis can occur during the course of many other causes of colitis and the intensity and distribution of ulceration is similar in all, often making it difficult to make a macroscopic diagnosis of the underlying disease.

326 In those fulminant colitides where the histologic features do not allow the nature of the colitis to be determined, all other clinical, radiologic, endoscopic, and histologic material should be reviewed. It is important to obtain pretreatment as well as post-treatment biopsies, since post-treatment changes may be misleadingly patchy. The length of history may be helpful: if long, the colitis is unlikely to be due to infection. Stool culture may also be helpful. The fulminant stage is one in which a diagnosis of indeterminate colitis may be appropriate if the histologic features do not allow a confidant distinction between UC and CD.

335If there has been a colectomy, with the rectum left in situ, and an ileostomy formed, the ensuing histologic changes in the diverted rectum are only helpful until the features of diversion disease supervene, usually a couple of months, after which the features of diversion disease dominate the picture and do not allow an insight into the underlying disease.

One helpful feature in this situation is the difference in response to diversion shown by CD and ulcerative proctocolitis patients. Diversion of the fecal stream in UC usually results in severe changes of diversion proctitis superimposed on UC, whereas in diversion of Crohn’s proctocolitis, there is often remission of the inflammatory changes.

336,

337 Diversion-related changes are usually well established within 3 months.

338Rectum in ulcerative proctocolitis following ileorectal anastomosis. The macroscopic and histologic changes in the rectum following ileorectal anastomosis are no different from those in the rectum in continuity with an inflamed colon. Biopsies from just above the anastomosis may be misinterpreted as small-bowel metaplasia. It is crucial that the pathologist is made aware of the previous operation of ileorectal anastomosis, when presented with a biopsy from this area. The dysplasia and carcinoma risk in this circumstance relates to the original disease extent: in total or extensive colitis, it will be as high as if the whole colon were still present. The pathologic changes of inflammation are quite different from those in the diverted rectum in UC.

Effect of medical therapy on the pathology of ulcerative colitis. It is possible that many of the difficulties concerning the classification of IBD on mucosal biopsies arise because of the effects of drug therapy, or of spontaneous remissions which can also be very focal. Furthermore, the difficulties are compounded by variations in the distribution of disease when modified by drug therapy, underpinning the importance of assessing multiple colonoscopic biopsies, from multiple sites, in the accurate diagnosis of IBD at the onset.

272,

273

Immunosuppressives have been used effectively in severe UC otherwise unresponsive to conventional medical therapy, and sometimes at the very outset.

339,

340 It has been recognized to have important consequences for the histopathologist and may lead to misdiagnosis of dysplasia.

341 The changes induced by cyclosporin include villiform mucosal regeneration and epithelial regenerative changes which are severe with marked nuclear enlargement, sometimes extending to the mucosal surface, but usually with plentiful eosinophilic cytoplasm. Perhaps, the most helpful feature is that the “pseudodysplasia” induced by cyclosporin is strikingly diffuse, with many and sometimes all crypts showing similar changes, in a way not usually associated with UC-associated dysplasia. Despite this, it is very important that the clinician alerts the pathologist to the fact that the patient has been on cyclosporine and that the pathologist is cautious not to overdiagnose dysplasia in this circumstance.

However, increasingly, TNF-

α antagonists are the drug of choice in steroid-resistant severe UC. Whether these have any distinct effect on the histology of the UC is still unclear and needs further study. These can have a dramatic effect on the amount of inflammation present, so that when resection takes place, the disease often appears relatively quiescent although linear ulcers may still be present (

Fig. 18-31).

342Where the features in individual biopsies, and especially in a series of biopsies, are being considered, marked variation in the quantity of acute and chronic inflammation within a biopsy or in a series of biopsies needs careful consideration. In intact (no erosion or ulcers) mucosa, it is possible in UC to get (a) relative rectal sparing of inflammation relative to proximal large bowel, and there may be no increase in chronic inflammation or (b) marked variation in both acute and chronic inflammation to the point that one part of the biopsy is heavily inflamed and the other is not. While this does occur in UC with treatment, one may need to ask is the question “Are there any other features present in this patient that might suggest the underlying disease is Crohn’s disease?”

Conversely, the typical biopsy of an aphthoid ulcer in CD with an erosion/ulcer on one side of the biopsy and the other side appearing normal is so typical of CD that even under therapy it needs to be considered. Such biopsies are only seen in UC in the severe/fulminant stage, when the clinical correlation should make the distinction easy.

Ileal pouches and their complications including pouchitis

Introduction Total proctocolectomy is an established surgical procedure for patients with UC and familial polyposis coli. While this may be followed with an ileostomy, various reservoir procedures have been proposed in order to create a more continent ileostomy. Initially, the double-folded ileal reservoir (Koch pouch) that has a large capacity had been used successfully for the construction of continent ileostomies, but used an artificial ileal valve and still required an ileostomy. It was almost completely replaced by the ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) after colectomy and mucosal proctectomy, as elimination is more physiologic and an ostomy is avoided. The term “pouchitis” was introduced by Koch to describe inflammation of a continent ileostomy.

343 It also refers to active inflammation of IPAA pouch mucosa. The condition is believed to be a “nonspecific, idiopathic inflammation of the neorectal ileal mucosa,”

344,

345 which really says nothing but sounds good.

Increasingly, IPAA has become the treatment of choice for younger patients with UC or familial polyposis, but as age increases, especially over about 60, results tend to be less satisfactory, possibly because blood supply and healing are poor. IPAA is not usually carried out for CD as disease recurrence in the pouch can be a disaster. However, under exceptional circumstances (e.g., young patients who might be psychologically devastated going through their developmental years with an ileostomy), it may be considered. The conditions necessary for this, apart from the understanding of the risk of pouch recurrence of the disease are (a) no terminal ileal or small-bowel disease, (b) no anal/perianal disease, and (c) disease limited only to the large bowel. Some patients appear to have results comparable to UC, but even a decade of usable function at this age may be worth the risk.

Pouchitis is the inflammation in an ileal pouch following a continent ileal pouch and is the most common long-term complication after pouch surgery for UC. The true incidence is difficult to determine, as it depends on diagnostic criteria used to define the

syndrome, the accuracy of the evaluation, and the duration of follow-up. Reported incidence rates vary between <10% in patients undergoing pouches for familial polyposis and up to around 60% in patients who had severe colitis with backwash ileitis. The risk for development of pouchitis is highest during the first 2 years postoperatively. Three to twenty percent of patients with pouchitis develop persistent or recurrent episodes of pouchitis that frequently require immunosuppressive treatment. It may or may not be accompanied by clinical symptoms. Clinically, pouchitis typically results in increased stool frequency, liquidity, urgency, abdominal and/or pelvic discomfort, and often fecal incontinence. Therapy is with antibiotics, usually ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. Other adverse sequelae include mechanical, inflammatory, functional, neoplastic, and metabolic conditions. Common causes of failure include pouchitis, pelvic sepsis, and poor function. Occasionally, patients with chronic pouchitis develop Crohn’s-like GI and systemic complications including enteric stenoses or fistulas in the small bowel immediately proximal to the pouch, perianal fistulas, pouch stenoses or fistulas, arthritis, and pyoderma gangrenosum. Various subtypes of pouchitis have therefore been distinguished. The most common form has been called “usual pouchitis.” Persistent or recurrent disease is termed “chronic or refractory pouchitis.”

345Because pathologists may receive specimens at a variety of stages, it is necessary to understand a little about how they are done to understand the type of specimen that is received. Most pouches are now constructed in more than one step, as it has fewer complications overall as follows:

1. One stage, that is, colectomy, pouch, no ileostomy— this is rarely done because the leak rate tends to be high. Rarely, it may be done in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) patients: but virtually never in UC. When it is done, the pathologist receives an extensive pan-proctocolectomy that includes a mesorectal excision for the rectum, but without the anus. The pathologist may be unaware that a pouch has been carried out.

2. Two-stage procedures are done in two ways:

a. Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy first, and at a later date removing the rectum and making a pouch without an ileostomy. These are done mainly in patients with acute disease or high doses of steroids or where the diagnosis is uncertain. So, the pathologist initially receives a subtotal colectomy and subsequently both the rectum, and an ileostomy. This tends to be “standard” in patients with colitis. In experienced hands, the leak rate appears not to be increased in patients in whom a subtotal colectomy is carried out first, and then the pouch constructed without an ileostomy.

b. In patients with quiescent disease, a proctocolectomy may be carried out with construction of the pouch and an ileostomy. Later the ileostomy is taken down, which the pathologist receives, and continuity established between ileum, pouch, and anus.

3. Three-stage procedure: Subtotal colectomy is carried out initially, and this is followed by proctectomy and pouch construction, with a “covering” ileostomy. Finally, the ileostomy is taken down and continuity established. This is rarely done unless at surgery, there are problems or concerns with the ileoanal anastomosis.

There are several options for the pouch itself, but a J-shaped pouch (small-bowel loop folded back on itself) or less commonly an S-shaped pouch (an additional loop of small bowel goes into the pouch) are the most common. After the pouch has been constructed, the anastomosis lines are given about weeks or months to heal, during which time, the patient has a temporary ileostomy.

At one time, the residual rectal mucosa was removed till the anal canal, as residual mucosa in familial polyposis can still develop adenomas, and in IBD is at risk for dysplasia and carcinoma. However, this tends to cause more issues with the anal sphincter than it solves, so there is usually a small residual “cuff” of distal large-bowel mucosa that still has the original disease. In patients with UC, this can become inflamed as part of the underlying disease (“cuffitis”).

Pouch complications and inflammation in the postoperative period is often related to anastomosis leaks or breakdown, and some may have an ischemic basis.

Etiology and Pathogenesis It seems likely that pouchitis represents a reaction to small-bowel contents with stasis. However, the fact that pouchitis is rare in familial polyposis, but more common (up to 60% of patients) with IBD suggests that there is much more to it than this. Indeed, many have wondered if it might represent recurrent IBD in the pouch, particularly when it develops a large-bowel phenotype (colonic metaplasia).

Predisposing factors for pouchitis include the extent of colitis, the presence of backwash ileitis, polymorphisms in genes like the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist, the NOD2/CARD, and noncarrier status of TNF allele. Other factors include preproctocolectomy thrombocytosis, preoperative corticosteroid use, extraintestinal manifestations, especially PSC, the presence of p-ANCA, being a nonsmoker, and the use of NSAIDs.

346Chronic pouchitis patients may, in their pouches, have increased levels of interleukins-1 (beta), IL-6 and IL-8, and TNF-a in the pouch mucosa similar to mucosa of patients with UC. Several studies have found that antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies occur more frequently in patients with chronic pouchitis than in those without pouchitis. The development of Crohn’s-like GI complications in patients with chronic pouchitis may engender concern as to whether the patient was operated for UC or CD. However, the diagnosis should only be changed if review of the original resected specimen shows features of CD (see subsequent discussion for CD in the pouch).

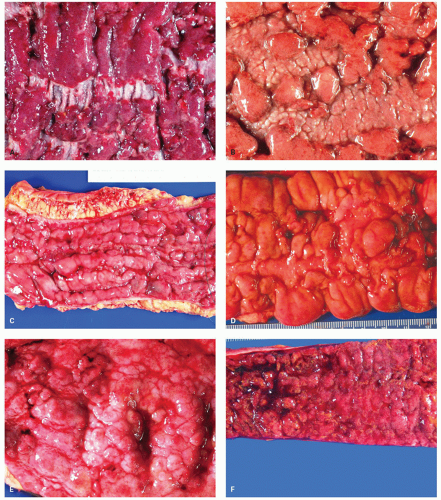

Diagnosis The diagnosis of pouchitis is based on clinical, endoscopic, and histologic criteria. While most pouches show some degree of inflammation on histology, pouchitis is diagnosed only when it is accompanied by symptoms and endoscopic abnormalities. The most frequent symptoms include increased stool frequency and fluidity, rectal bleeding, abdominal cramping, urgency and tenesmus, and in the most severe cases, incontinence and fever. The most frequent endoscopic features include mucosal erythema, edema, friability, petechiae, granularity, and loss of vascular pattern, mucus exudates, erosions, and small superficial ulcerations (

Fig. 18-32). Because of the great variability in the results of reports on the incidence of pouchitis, Sandborn and colleagues developed a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI).

347 This index consists of 18 points, calculated from three separate 6-point scores: symptoms, endoscopy, and histology. A score of 7 or more indicates active inflammation. The histology scale is composed of “polymorphonuclear infiltration,” subdivided into mild, moderate (crypt abscess) and severe, and mean “ulceration” per low-power field.

347 Overall, clinical diagnosis based on symptoms is accurate in only 55% of the patients.

348 Before treatment is started, it is important therefore to establish a correct diagnosis and to consider other causes of pouch dysfunction and inflammation, such as infections, irritable pouch syndrome (an IBS-like disorder affecting the pouch), and cuffitis. It has been suggested that irritable pouch syndrome may have an excess of serotonin-producing enterochromaffin cells, when compared to normal (not inflamed) pouches, but the overlap between groups was not sufficient to be of practical value.

346

Histology Usual pouchitis is characterized by the presence of a typical polymorphonuclear (neutrophil) infiltrate in the lamina propria and the epithelium in association with an increase in chronic inflammatory cells in the lamina propria (

Fig. 18-33). Most commonly, neutrophils remain in the lamina propria with relatively little epithelial infiltration. In more severe cases, patchy intraepithelial neutrophils become more numerous and induce cryptitis, crypt abscesses, pyloric gland metaplasia, erosions, and ulcers (

Fig. 18-33). The more severe grades of inflammation correlate well with the frequency of defecation and endoscopic appearance of inflammation. The inflammatory changes often have a patchy distribution with very focal erosions and ulcers (

Fig. 18-33B), to the point that elsewhere in the GI tract, CD would immediately enter the differential diagnosis. However, this diagnosis is elusive in pouches as there can be marked overlap in morphology between CD and pouchitis. Two regions of the pouch, the lower and posterior, are the most frequent sites of characteristic findings. Consequently, a single random biopsy has limited diagnostic value.

349 Histologic examination of pouch biopsies shows following features.

a. Acute inflammation and its sequelae: Neutrophils are rarely present in normal-appearing pouches.

350 However, normal pouches are seldom biopsied, except when symptoms suggestive of pouchitis that are refractory to usual therapies are present.

b. Architectural changes: These vary from reduction in villous height often with crypt hyperplasia, to marked changes seen following ulceration, analogous to the changes seen in UC. Villous blunting and crypt hyperplasia may be a normal feature of healthy pelvic ileal pouch.

c. Colonic metaplasia: The concept of “colonic metaplasia” implies not only an almost flat mucosa resembling colonic mucosa but also a change in the type of mucin. If an alcian blue pH 2.5-high iron diamine stain is carried out, the pouch mucosa may show metaplasia to a large-bowel phenotype that,

unlike usual small bowel, does not produce the sulfated mucins. It is also supported by experimental data showing a different pattern of the expression of human tropomyosin isoform 5 (hTM5) in the ileal pouch. In genuine ileal samples, hTM5 is not expressed or focally expressed only in goblet cells. Pouch biopsies obtained at 6 months after surgery in one study showed a diffuse hTM5 staining in the goblet cells and in the nongoblet cells lining the crypts and the lumen. These changes are associated with shortening and reduced number of the villi.

351 It has been suggested that these changes represent an adaptive response. “Colonic metaplasia” occurs more frequently in cases with severe pouchitis, suggesting that it may be a “reparative” rather than an “adaptive” response, although this can be interpreted either way.

352

d. Pyloric metaplasia: This is seen readily as a response of the small bowel to ulceration, so it is not surprising to find that it is seen particularly in pouches that have had severe ulceration (

Fig. 18-33D).

353

e. Muscle changes: As expected, following ulceration there is often duplication of the muscularis mucosae, as seen elsewhere in the GI tract, and submucosal fibrosis. There may also be fusion between the muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria.

f. Chronic inflammatory changes: These are found in most (up to 87%) of the pouches.

354 The findings consist of infiltration of the lamina propria by a variety of cells such as lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and histiocytes. Increase in IEL in the pouch seems not to be part of pouchitis, and if marked should raise the possibility of associated celiac disease.

g. Granulomas: These can also be part of pouchitis, but largely represent mucin granulomas (

Fig. 18-33G). Great care should be taken not to interpret these biopsies as being “consistent with Crohn’s disease,” as this becomes translated clinically into the patient having “histologically proven CD of the pouch.”

In patients presenting with chronic refractory pouchitis, possible causes such as infections (particularly CMV) must be considered.

Other causes of pouch problems. These include a variety of noninflammatory conditions of the pouch, but biopsy may be carried out to exclude pouchitis. These include symptoms resulting from decreased pouch compliance, irritable pouch syndrome, strictures (inlet, outlet, anastomosis lines) efferent limb syndrome, decreased pouch emptying, and pelvic floor dysfunction. Endoscopy and biopsy are critical in excluding pouchitis to distinguish these—unless it coexists. Usually, when pouchitis causes symptoms, it is quite severe with erosions and ulcers. Minor chronic inflammation appears not to be associated with symptoms.

When are pouch biopsies done? Pouchoscopy with biopsies may be carried out for pouch dysfunction symptoms—usually when not responding to antibiotics, to confirm or refute pouchitis, or delineate other potential causes of diarrhea, and if pouchitis is present, the question of whether a treatable cause is present such as

C. difficile or CMV infection. The question of whether CD is present may be asked, but this diagnosis is fraught with hazard (see subsequent

discussion). The presence of “cuffitis” (inflammation in the residual couple of cms of rectal cuff—most distal rectum) can cause symptoms similar to ulcerative proctitis, but can be surprisingly difficult to treat. An occasional problem is that of the presence of “prepouch ileitis” (see subsequent discussion).

Pouchoscopy may also be carried out in patients with FAP, as there may be recurrence of adenomas, and rarely carcinomas, in both the pouch and the rectal cuff mucosa. Similarly, inflammatory polyps may form especially at anastomosis lines, but also as a result of pouchitis. In patients with IBD, while dysplasia and carcinoma are rare they are well described (see subsequent discussion).

Standard Biopsy Run in Pouches Besides examining and biopsing any lesions (severe inflammation, ulcers, raised lesions, or polyps) in the pouch and rectal cuff, the prepouch ileum should also be examined and biopsied (proximal and distal prepouch ileum), especially if any lesions are present.

Reporting Pouch Biopsies If biopsies are without significant abnormality—say so. However, most pouches are inflamed and the inflammation can be localized, patchy, or diffuse with or without erosions and ulcers.

The quantity of acute and chronic inflammation can be subjectively graded as mild, moderate, and severe, and associated features also described (erosions, ulcers, etc.). However, this represents tradition rather than being of much clinical value unless marked, and is likely not reproducible unless severe. The presence of marked villous blunting, erosions, and ulcers or other features indicative of ulceration (pseudopyloric metaplasia) are noteworthy as they can be associated with severe pouchitis. Granulomas, whether related to ruptured crypts (mucin) or foreign body are reported, but care should be taken not to report these as being “consistent with Crohn’s disease.” An intraepithelial lymphocytosis is not part of pouchitis and should raise the question of the usual causes of an intraepithelial lymphocytosis, especially celiac disease. There is a single case report of a patient with collagenous colitis who underwent proctocolectomy and IPAA for refractory disease.

355 The changes did not extend into the afferent limb, neither was the cuff of terminal ileum in the proctocolectomy specimen involved. Both symptoms and collagen band in the pouch resolved following antibiotic therapy,

355 implying once again the potential role of luminal contents, especially bacteria in its genesis.

The presence of dysplasia or neoplasia clearly requires a comment. The presence of dysplasia or carcinoma in pouches is rare, but well described and those with dysplasia or carcinoma in the resected colectomy specimen are at a higher risk. Some patients with FAP regularly seem to produce adenomas in the pouch.

Changes in Resected Pouches About 10% of pouches are ultimately removed. This is usually the result of failure of medical treatment, the presence of fistulas, and is usually carried out sometime after a defunctioning ileostomy has been carried out. The features found may therefore be those of either pouchitis or “diversion disease” or both, and can closely resemble CD histologically.