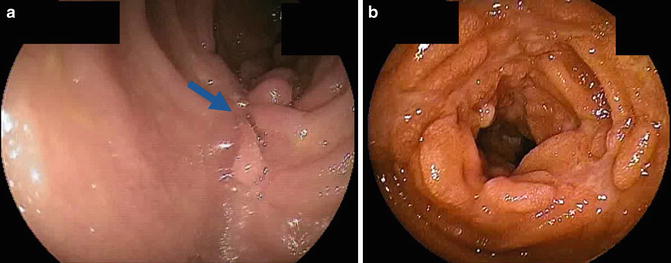

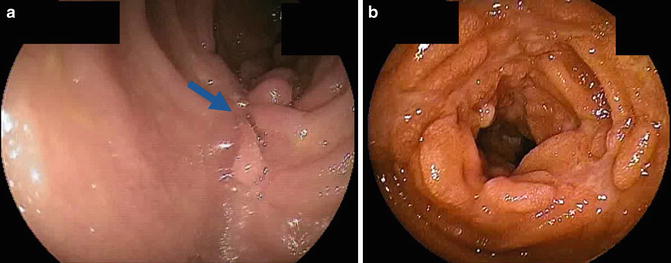

Fig. 10.1

CD SB lesions of varying degrees of severity, SBCE views. These appearances are not specific to CD and may be induced by other etiologies (including other inflammatory conditions and the use of pharmacological agents; e.g., NSAIDs). Images: Prof. O. Epstein, Ms. H. Palmer, Dr. M. I. Hamilton and Dr. E. J. Despott, Royal Free Unit for Endoscopy, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust

Capsule retention (CR)—defined as an SB capsule remaining within the GI tract for at least 2 weeks or requiring urgent medical, endoscopic or surgical intervention for retrieval [29]—is the main potential complication of SBCE. Given the propensity for SB stricture formation in CD, precautionary measures to avoid CR require particular attention in this setting. Although for suspected CD the CR rate is low (of the order of 1.6 % and comparable with other indications for SBCE), the rate of CR in patients with known CD has been reported to be as high as 13 % [30–33]. This highlights the critical requirement for clinicians to actively attempt to exclude the presence of stricturing disease by direct questioning for abdominal pain and other obstructive symptoms and appropriate use of the PillCam™ patency capsule (PC) (Given Imaging, Israel) and “pre-test” cross-sectional imaging where SBCE is indicated [34–36].

Comparisons of SBCE with Dedicated SB Radiological Imaging

A meta-analysis by Dionisio et al. compared the diagnostic yield (DY) of SBCE and other diagnostic imaging modalities (including SB follow-through [SBFT], CTE, and MRE) in patients with suspected or known CD [22]. This showed a significant incremental yield (IY) for SBCE as compared with SBFT and CTE in the setting of suspected CD (SBCE versus SBFT IY = 32 %, P < 0.0001 and SBCE versus CTE: IY = 47 %, P < 0.00001). While this meta-analysis has shown a similar performance for SBCE and MRE, a prospective study by Jensen et al. in 93 patients with suspected or known CD comparing SBCE, CTE, and MRE (using ileo-colonoscopy [IC] as the gold standard) showed that SBCE may be more sensitive than MRE for the detection of subtle mucosal lesions and proximal SB pathology [37]. CTE and MRE have been shown to have similar sensitivities and although MRE provides a safer option for patients by the avoidance of ionizing radiation, this technology is more expensive and less widely available [38, 39].

A previous prospective, randomized 4-way comparison of SBCE, CTE, SB follow-through (SBFT) and IC by Solem et al. [16] performed in patients with suspected (or known) CD (using consensus criteria as the reference standard) showed similar sensitivities (83 % for SBCE, 67 % for CTE and IC, and 50 % for SBFT) but lower specificity for SBCE as compared with the other tests (100 %, P < 0.05). These results underline the importance of interpretation of SBCE findings within the appropriate clinical context [16]. Pre-test patient selection by the use of objective parameters (including clinical manifestations and serological inflammatory markers), as recommended by the International Conference on Capsule Endoscopy (ICCE) [40] and fecal calprotectin may enhance the specificity and positive predictive value of SBCE findings [41–48]. Given that NSAIDs may induce similar SB mucosal lesions to those seen in the presence of active CD, thorough exclusion of recent use of these agents should also be actively sought while investigating patients with SBCE in this setting [28, 49, 50].

Comparisons of SBCE with Flexible Endoscopy

In their meta-analysis, Dionisio et al. showed that when compared with push enteroscopy (PE), SBCE had an overall weighted incremental yield (IYw) of 42 % and within the same comparison, for the sub-groups of patients with suspected and known CD SBCE had an IYw of 18 % and 57 % respectively [22]. This meta-analysis also showed that SBCE had an overall IYw of 39 % when compared with ileo-colonoscopy (IC). Sub-group analysis of patients with suspected and known CD for the latter comparison showed a SBCE IYw of 22 % and 13 % respectively [22]. In their 4-way comparative study, using clinical consensus as the gold standard, Solem et al. showed similar sensitivities for IC and SBCE but higher specificities for IC [16]. Two additional studies [51, 52] compared these two modalities for the assessment of postoperative SB CD recurrence and although the results were at variance, both studies showed that SBCE detected more proximal lesions than IC.

A meta-analysis from the Mayo Clinic [53] demonstrated similar diagnostic yields for SBCE and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE). In another meta-analysis [54] although SBCE appeared to have significantly higher diagnostic yield than DBE performed via either anterograde or retrograde route alone, the yield of positive findings for these two endoscopic modalities was similar when DBE was performed via both routes combined.

Role of SBCE in the Diagnosis and Management of IBD

Suspected CD

Since up to 90 % of patients with SB CD have terminal ileal involvement [55], IC is considered to be the first choice of endoscopic investigation to help establish a diagnosis of CD [6]. In cases where IC is not attainable or remains inconclusive [56, 57] and there is no clinical evidence to support the presence of obstructive disease, SBCE may be considered for the assessment of the SB mucosa; otherwise CTE or MRE should be the investigation of choice [2, 12]. The clinical value of any SBCE findings and its cost-effectiveness would be enhanced by careful patient selection with application of pre-test probability criteria [41–48] and avoidance of potential confounding factors e.g. recent NSAID use [12, 28, 49, 50].

Known CD

In the presence of known CD, further assessment of the SB is frequently warranted for staging of disease activity in the presence of symptoms regardless of IC findings [6, 12]. In this setting, cross-sectional radiological imaging in the form of CTE or MRE takes precedence since these would facilitate the identification of stricturing and or transmural/extramural disease activity and associated complications while also allowing enhanced anatomical mapping of disease extent and distribution [2, 6, 12] (Figs. 10.2 and 10.3). The use of SBCE may still be warranted if cross-sectional imaging in patients with known CD remains inconclusive, if there are ongoing symptoms, and/or if any additional findings may influence patient management [24, 37]. However, clinicians should be mindful of the higher risk of CR in this setting. Ensuring functional SB patency by the use of a PC is considered mandatory if SBCE is to be undertaken in patients with known CD [2, 12].

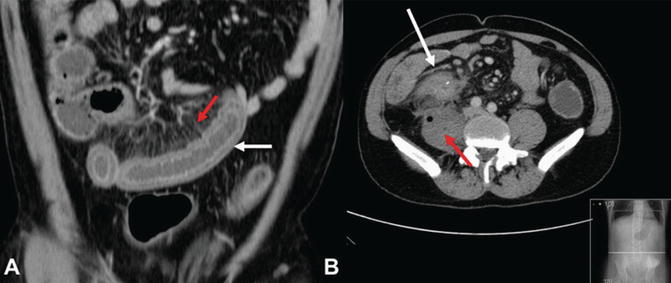

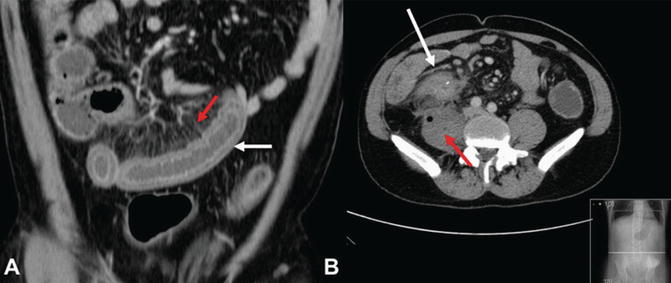

Fig. 10.2

(a) Coronal plane CTE image in a patient with active CD demonstrating an inflamed ileal loop with mural thickening and hyper-enhancement (white arrow) and prominence of the mesenteric vasa recta (the “comb sign”) (red arrow). (b) Transverse plane CTE image of another patient with active CD demonstrating an inflammatory mass at the ileo-colic anastomosis (white arrow), which has fistulated into the right psoas muscle causing an intra-muscular abscess (red arrow). Images: Courtesy of Drs Abdullah Sharif and Katie Planche of the Department of Radiology, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust

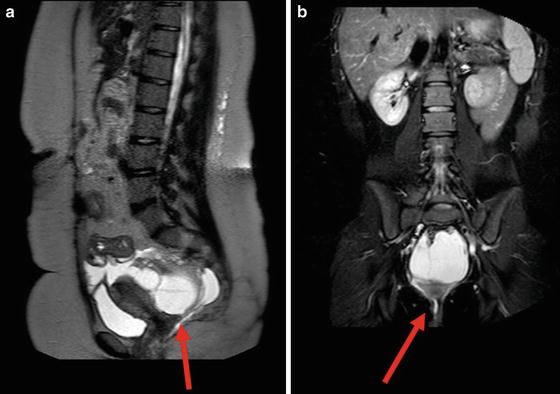

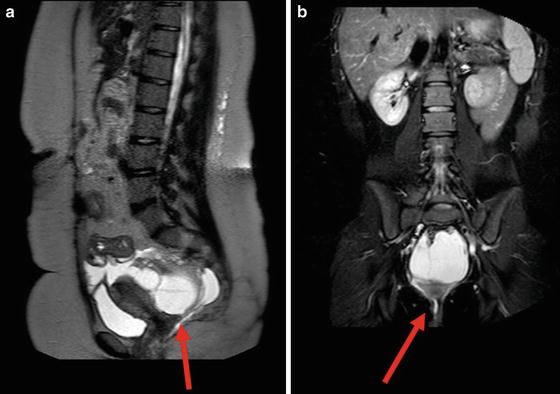

Fig. 10.3

MRE images in a patient with active CD and previous pan-proctocolectomy demonstrating a loculated pelvic fluid collection and perineal fistula (red arrows). (a) Sagittal plane. (b) coronal plane. Images: Courtesy of Drs Abdullah Sharif and Katie Planche of the Department of Radiology, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust

Assessment of CD severity as a guide to management can usually be undertaken by dedicated SB cross-sectional imaging, however, three retrospective studies have also demonstrated the potential usefulness of SBCE in this regard [58–60]. Another retrospective study of patients with known CD (n = 108) by Flamant et al. [61] focused on the clinical importance of jejunal disease detected by SBCE. This study from France demonstrated the presence of jejunal lesions in 56 % of patients (17 % of these had solitary jejunal disease) and found that jejunal disease was independently associated with a higher risk of relapse, suggesting the underlying presence of a more aggressive CD phenotype. In another retrospective study from France (n = 71; 3 month follow-up) lesion severity as assessed by SBCE led to an adjustment of medical management in 54 % of patients. The role of SBCE for the assessment of mucosal healing is also being assessed [62, 63], albeit this indication has not yet been recommended for use in routine clinical practice. More objective disease activity indices such as the Capsule Endoscopy Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CECDAI) (Niv score) or Lewis score may help to standardize reporting of disease activity identified at SBCE in clinical trials and clinical practice [64, 65].

IBDU and UC

In the setting of IBDU, although the supportive evidence is scant and mainly relates to the findings of one retrospective study (n = 120) [66] and three small prospective studies [67–69], mucosal lesions compatible with SB CD have been reported in 17–70 % of patients with previously unclassified disease [66, 67, 69]. Within the appropriate clinical context, SBCE therefore may be a useful modality to assist reclassification and may lead to modification of disease management strategies in patients with this condition [2, 12, 70]. The role of SBCE in UC remains limited but it may be useful in patients who manifest atypical symptoms and in those with unexplained iron deficiency [2, 12, 71]. Usefulness of SBCE in the preoperative assessment of patients undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) surgery was investigated prospectively by Murrell et al. in a longitudinal study of 68 patients [72]. At 12 months follow-up, the results of this study showed no significant correlation between preoperative SBCE findings and IPAA outcome. Pre-IPAA assessment by SBCE therefore appears to be of limited value and is currently not recommended in day-to-day clinical practice [2, 12].

Flexible Enteroscopy

The development of DAE over the last decade has allowed minimally invasive, flexible endoscopic access to the depths of the SB with far less restriction than ever before. The term DAE is used to collectively describe flexible enteroscopic technologies that use device assistance to apply gentle SB wall traction to minimize SB stretching and looping in order to facilitate advancement of a dedicated enteroscope deep into the SB. DAE comprises balloon-assisted and spiral enteroscopy technologies (BAE and SE, respectively), which all make use of a flexible stabilizing overtube and enteroscope. BAE collectively describes the main types of DAE that employ the use of balloon-assisted SB traction. Double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) (Fujifilm, Saitama, Japan) incorporates the use of two balloons [11, 73] while single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) uses a single traction balloon respectively [8, 10]. SE (Spirus-Medical™, Stoughton, MA, USA) does not incorporate balloon traction but alternatively makes use of a soft-plastic spiral for SB traction [74].

Since DBE was the first type of DAE technology to be introduced into clinical practice [73, 75], most of the evidence is DBE related [76–83], albeit experience with other DAE technologies is also increasing [7, 84–90]. Although DAE is considered complimentary to SBCE and this is often used to guide further evaluation and/or therapy by DAE [91, 92], the potential presence of SB strictures may preclude the use of SBCE in patients with CD and recourse to DAE is often guided by SB cross-sectional imaging findings in this condition [93].

The main advantages of DAE relate to its ability to allow direct assessment of the SB mucosa (via the anterograde or retrograde routes), facilitation of tissue biopsy, and the application of endotherapy. In the setting of CD, DAE therefore may assist with confirmation of diagnosis, evaluation of disease activity and response to medical therapy, facilitation of endoscopic balloon dilatation (EBD) of SB strictures (in appropriately selected cases), and with retrieval of retained SB capsules [2, 12, 76, 79–83, 93–97]. Disadvantages of DAE include its relative invasiveness and procedure duration (often in excess of 60 min) [98]. DAE proficiency requires dedicated training. In addition, there are technical challenges particularly related to the retrograde-route and those patients with prior surgery and extensive adhesions, which may hinder success [99, 100]. DAE has been shown to be safe and complication rates are of the order of about 1 % overall and up to 9 % for procedures involving endotherapy [7, 83, 84, 94, 101–103].

Role of DAE in the Diagnosis and Management of IBD

Diagnosis and Assessment

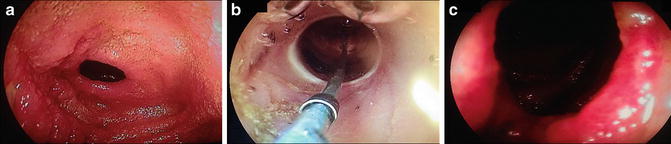

A key meta-analysis from the Mayo clinic by Pasha et al. (11 studies, including 9 that compared yield of inflammatory lesions) confirmed that DBE and SBCE had similar diagnostic yields [53]. This was also demonstrated by another meta-analysis (including eight studies) [54], which showed that the yields of bi-directional DBE and SBCE were similar. For diagnostic and assessment purposes, DAE is usually reserved for cases where other less-invasive investigations remain inconclusive or where histopathological corroboration (to rule out infection or malignancy) is deemed to be essential [2, 12, 104]. When DAE is clinically indicated, correlation with other imaging modalities allows for “targeting” of suspect lesions and may enhance its diagnostic yield and clinical effectiveness [76, 80, 91, 103]. Direct evaluation of SB mucosal lesions is also useful for the diagnostic process and the presence of mesenteric border SB ulceration has been shown to be highly suggestive of underlying CD [81] (Fig. 10.4). A small pediatric study (n = 20) from the Netherlands, which compared the findings of SBE with ultrasound (+ Doppler) and MRE, found that SBE facilitated definitive diagnosis of active CD in 14/20 patients (70 %) and suggested that earlier use of DAE may expedite the diagnostic process [85]. DAE may also be useful in the guidance of medical management by direct endoscopic assessment of disease activity [78, 93, 96, 105]. In a retrospective study of 40 patients with established CD, Mensink et al. [96] showed that DBE identified active SB disease in 24 (60 %) patients and as a result, management was altered in 75 % of those with positive findings. These results were confirmed by another prospective longitudinal study performed by the same investigators in another 50 patients with known CD. In this second study, the findings at DBE had a direct impact on the medical management of 38 % of patients, 88 % of whom remained in remission with a significantly improved Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) at 12 months of follow-up [93].

Fig. 10.4

CD SB lesions as seen at DBE in two different patients. (a) Healing ulceration at the mesenteric side of the ileum (blue arrow). (b) Severe ulceration and edema affecting the jejunum, leading to inflammatory stricturing. Images: Dr E. J. Despott, Royal Free Unit for Endoscopy, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust

Endotherapy of SB Strictures at DAE

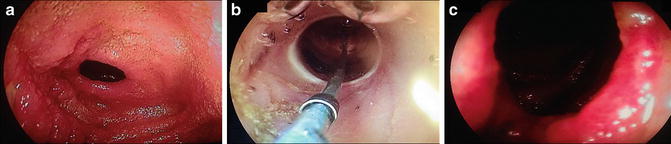

Within the appropriate clinical setting, selected CD-related strictures may be amenable to endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD). This has been shown to be effective and may reduce the need for surgical intervention in some patients [75–77, 79, 82, 94, 97, 106]. In order to reduce the risk of major complications (which may be of the order of 2–11 %) and enhance clinical effectiveness, careful patient selection is mandatory [76, 94, 97]. Prior to consideration for EBD, SB cross-sectional imaging should be used to evaluate stricture anatomy and characteristics, length, number and location [76, 94, 97]. EBD of shorter strictures, less than 5 cm, is associated with better clinical outcomes [76, 79, 94, 106] and the presence of severe, active inflammation and angulated stricture morphology should discourage the use of EBD since this may increase the risk of iatrogenic perforation [76, 79, 94, 97]. In order to further reduce risk, adequate endoscopic views (avoiding tight angulation) and a stable enteroscope position should be obtained before EBD is considered [76, 94, 97]. Intra-procedure fluoroscopy may enhance safety and outcome [94, 97] and is recommended. The most frequently used technique for EBD employs the use of a transparent, wire-guided, through-the-scope (TTS) balloon dilator—e.g., controlled radial expansion (CRE™) (Boston Scientific, USA) or Hercules™ (Cook Medical, Ireland)—which allows EBD to be performed under direct endoscopic vision [76, 94, 97] by water insufflation to the required pressure and balloon diameter for 1–2 min [76] (Fig. 10.5).

Fig. 10.5

EBD of a short (mainly fibrotic) CD-induced jejunal stricture using a through-the-scope CRE™ (Boston Scientific, USA) transparent, wire-guided balloon dilator under direct endoscopic vision at DBE. (a) Pre-EBD. (b) during EBD. (c) post-EBD, (c) Images: Dr E. J. Despott, Royal Free Unit for Endoscopy, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust

Three studies have focused on outcomes of EBD of SB strictures in patients with CD [76, 79, 94]. Pohl et al. attempted EBD of CD-related strictures in a study of 19 patients [79]. EBD was considered suitable in 10/19 and at 10 months follow-up, 6 of these patients remained asymptomatic and without the need for surgery. Despott et al. performed a study in 11 patients with confirmed CD SB strictures who were referred for DBE-facilitated endotherapy [76]. EBD was achieved in 9/11 patients. In the remaining two patients, adhesive disease prevented enteroscopic access to the strictures. One patient with actively inflamed strictures suffered a delayed perforation, warranting surgical resection of the diseased SB. At a mean follow-up period of 20.5 months, the remaining eight patients experienced significant symptomatic relief after EBD as noted by improved symptom-related VAS scores. Although two patients required repeat EBD, none of them required surgery. Similar findings were shown by Hirai et al. [94]. In their study of 25 patients, EBD was successful with regard to short-term dilation in 18/25 (72 %). Although two patients suffered major complications (pancreatitis and hemorrhage) cumulative surgery-free rates at 6 and 12 months follow-up were 83 % and 72 %, respectively. The concept of biodegradable SB stents [107] that may be deployed at DAE for potential improvement of longer-term outcomes in this setting merits further study.

Conclusion

The emergence of advanced, complementary endoscopic and radiological technologies over the last decade has greatly refined our ability to assess the SB for pathology in patients with suspected or known/established IBD. Given the absence of a diagnostic gold standard, the interpretation of endoscopic and radiological findings requires corroboration with clinical and other investigation results. Although the relative role of each of these SB imaging technologies in practice shall ultimately be governed by individual clinical scenarios, access to local resources and patient preference, the application of pre-test criteria and consideration of dedicated international consensus guidance may further enhance their clinical and economic effectiveness.

The use of DAE is likely to continue to be reserved for cases where direct endoscopic and histopathological evaluation is required and for selected cases where EBD of SB strictures is indicated. The impact and potential future role of SB endoscopy in the evaluation of mucosal healing and response to medical management strategies warrants further investigation.

Disclosure

E. J. Despott has received education and research grants from Aquilant Medical (UK), Fujifilm and Keymed-Olympus.

References

1.

Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46.PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree