IMMUNODEFICIENCY DISORDERS OF THE INTESTINAL TRACT

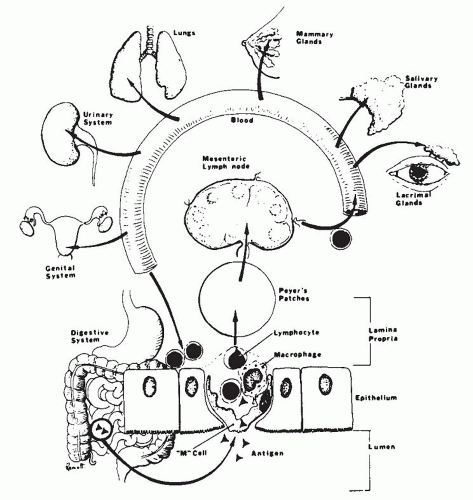

The GI tract is frequently an important target organ in the primary as well as secondary immunodeficiency disorders

66,

67 because it is constantly exposed to a heavy antigen load. Immunodeficiency is usually suspected by the clinician when patients have a history of either prolonged infections or infections caused by unusual organisms. The pathologist’s role is largely to confirm and identify the frequent complications of immunodeficiency, of which infection and neoplasia are the most important. On occasion, the pathologist may be able to document the type of immunodeficiency through the

use of immunohistochemistry. Sometimes, unexpected histologic changes may be found in the gut, such as nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and giardiasis, which should lead one to suspect an immunodeficiency disorder in a clinically unsuspected case. As common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is so common, it may sometimes be detected in relatively asymptomatic patients because of a paucity of IgA plasma cells in the lamina propria with no compensatory increase in other classes of plasma cells.

There are two major categories of immunodeficiency disorders: primary and secondary.

Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders These disorders include a large and varied group of diseases

66,

67 resulting from impairment of the B- and T-cell systems, abnormalities of phagocytic function, or both. The functional interaction of B and T cells and monocytes in the expression of the immune system makes the division of immunodeficiency diseases into B- and T-cell disorders somewhat artificial.

6,

68,

69 Nevertheless, usually either the antibody defects or cell-mediated abnormalities predominate, allowing for a practical subdivision of the immunodeficiency disorders. In addition, genetic defects have been described in conditions such as food intolerance, in which there appear to be specific abnormalities in responsiveness to certain antigens. In these disorders, there appears to be poor antigen clearance or heightened responsiveness, leading to immune complex disease or hypersensitivity reaction.

70 In adults, common variable or late-onset immunodeficiency, and selective IgA deficiency are by far the most common immunodeficiency disorders.

15,

68,

71 In children, severe combined immunodeficiency disease is the most common. It usually presents soon after birth. Its diagnosis is important to prevent the sequelae of acute and chronic infection.

2

Secondary Immunodeficiency Disorders These disorders are becoming more common. Some develop following infections, while others are iatrogenic complications of immunosuppressive therapy, radiation therapy, or bone marrow/hemopoetic stem cell transplantation (BMT/HSCT). The most important secondary immunodeficiency is acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), which is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

72 There is considerable evidence to suggest that immune mechanisms are involved in the tissue injury of a number of GI disorders, such as idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease, celiac sprue, and Whipple’s disease. The precise pathogenic mechanisms of these disorders remain to be elucidated and they are discussed further under each disorder.

Clinical features. Clinically, patients usually present with chronic diarrhea and malabsorption, although other symptoms may also occur based on the specific disorder (primary or secondary immunodeficiency) and its complications. The main impairment of the immune system is characterized by a decreased resistance to infection and in some cases, subsequent neoplasia.

72,

73,

74 The nature of the infection depends on the specific defect. Thus, patients with impaired B-cell function are most susceptible to bacterial and certain parasitic infections. In contrast, those with impaired T-cell function have defective cell-mediated immunity, leading to sprue-like disorders, pernicious anemia, nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, inflammatory bowel disease,

74 and an enhanced susceptibility to prolonged viral, fungal, and mycobacterial infections. The major clinical manifestations of these infections will depend on the primary site of involvement in the GI tract.

75

The diagnosis of the primary immunodeficiency disorders is usually made readily. Patients commonly have a history of recurrent, prolonged opportunistic infections, such as pneumocystis pneumonia, giardiasis, or cryptosporidiosis. The finding of associated disorders, such as respiratory tract infections and autoimmune disorders in CVID, helps greatly in determining the precise immunologic abnormality and there is frequently a family history of immunodeficiency disease.

The categorization of the immunodeficiency disorders is based primarily on three categories of immunologic tests for humoral (B-cell) and cell-mediated (T-cell) immunity, that is, immunoglobulin concentrations, antibody formations, and cell-mediated immunity (

Table 3-1).

68,

69Histology. The pathologic changes accompanying the primary immunodeficiency disorders depend in part on the specific immunologic defect (

Table 3-2). It should be stressed that in some cases there may be no significant histologic alteration. The most frequently seen histologic lesions are the results of complications, specifically infections. Intrinsic lesions of immunodeficiency are uncommon. The histologic changes fall

into four major categories as described in the paragraphs that follow.

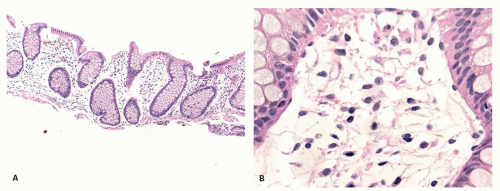

No Change There may be no significant alteration or reduced number of inflammatory cells of the lamina propria (

Fig. 3-7). For example, in late-onset immunodeficiency disease, there may be an absolute marked reduction in plasma cells. Occasionally, plasma cells are not reduced markedly. Rather, there is a reduction of IgA-containing plasma cells with a compensatory increase in the number of the other plasma cells, especially those containing IgM. Immunostains will show the specific cell type that is altered, for example, a diminution in number or absence of IgA-containing plasma cells.

Mucosal Lesions Resulting from Infections or Bacterial Overgrowth Infections in patients with immunodeficiency disorders tend to be more prolonged and cause more damage in the immunocompromised setting. Patients are especially prone to infections by multiple organisms, frequently of low virulence, which are not normally pathogenic to man. These include the normal commensals of the GI tract,

76 fungi such as

Candida,

77 and viruses such as Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes.

68,

71,

76,

77 The patients are also unable to mount an effective host response to unusual organisms, not normally found in the GI microflora, such

Giardia lamblia,

Trichomonas hominis,

Isospora belli, and

Cryptosporidium.

78,

79,

80,

81

The histological changes in the immunocompromised patient differ from those found in the normal patient. For example, the inflammatory response may be muted in infections such as giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, and CMV infection. By contrast, it may be exaggerated in some cases of CMV and herpetic infections such as those seen in AIDS patients. Certain histologic changes should alert the pathologist to the possibility of an unsuspected immunodeficiency disorder, for example, the finding of invasive esophageal candidiasis in AIDS or benign nodular hyperplasia in a new case of giardiasis.

The specific histologic changes in the GI tract resulting from infection will also vary somewhat with the site of involvement. In the esophagus, stomach, and large intestine, the lesions consist primarily of mucosal erosions.

75,

76 In candidal infections, particularly

of the esophagus, the organism is present in the superficial necrotic debris and may invade the mucosa and occasionally extend through the bowel wall. In viral infections, inclusions tend to be scant and are frequently missed unless serial sections are carefully screened. The viral inclusions are commonly associated with mucosal erosions and ulcerations, often with minimal inflammation in the early stages.

82 In AIDS, herpetic infections may be particularly intractable, especially herpetic proctitis, characterized by burrowing ulcers and destruction of the sphincter.

81In the small intestine, bacterial overgrowth or parasitic infections characteristically produce mucosal lesions. However, unlike celiac sprue, the mucosal lesion is often patchy and of mild or moderate severity.

71 Occasionally, crypt abscesses and a neutrophilic infiltrate of the lamina propria are seen.

75 The infections are usually due to bacterial overgrowth with aerobic and anaerobic coliforms, or protozoal infestations.

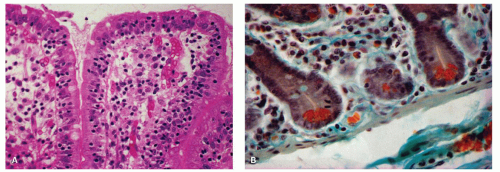

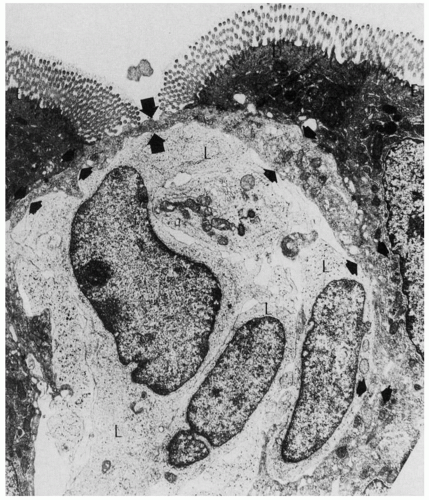

75 Giardiasis is the most common parasitic infection. The organism is found in the intestinal mucus or adherent to the epithelial microvillous surface (

Fig. 3-8)

83 and, on rare occasions, within the columnar epithelial cells.

84 The only other significant protozoal infections described are the coccidial infections. Coccidia (e.g.,

Cryptosporidium and

Isospora) are common parasites in the intestinal tracts of animals and are generally transmitted by ingestion of contaminated food or water.

80 Infections in man were once thought to be very uncommon and were usually associated with immunodeficiency states. However, recent studies of cryptosporidiosis have shown that they are a common cause of gastroenteritis in children.

85 In

Isospora infections (

hominis and

belli), the parasites are found within the epithelial cell cytoplasm of the mucosa, and all stages of its life cycle have been observed. In contrast,

Cryptosporidium (a coccidial protozoan related to

Isospora) inhabits the striated or microvillous border of the small intestinal epithelium and, less commonly, the gastric, rectal, and billiary mucosa.

80 In general, these infections are self-limited when they occur in the normal population. However, in the immunodeficient patient, they cause prolonged illness, and in the case of cryptosporidiosis no effective therapy is available.

Intrinsic and Associated Morphologic Changes Although the mucosal injury in the immunodeficient patient is frequently the result of superimposed infection, in certain disorders, there may be an intrinsic change independent of any recognized infection.

12 For example, a case of IgA deficiency has been described, which had a severe “flat” mucosal lesion similar to that seen in celiac sprue, but the patient did not respond to a gluten-free diet. This patient was found to have an IgG antiepithelial cell antibody.

86 In the stomach, pernicious anemia with gastric atrophy is found in some late-onset immunodeficiency syndromes. It occurs in younger patients (earlier than the usual 40-60 years

of age), lacks plasma cells in the atrophic mucosa, and lacks antibodies to intrinsic factor and parietal cells.

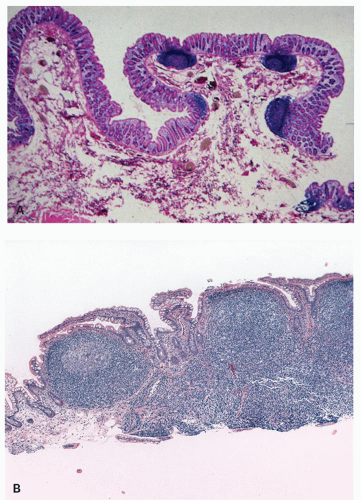

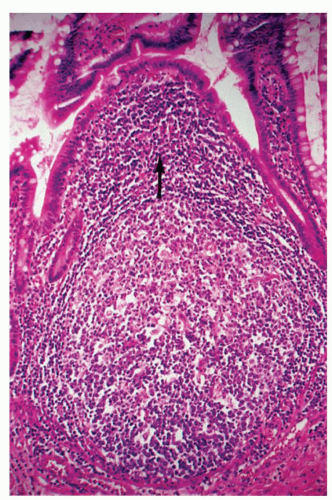

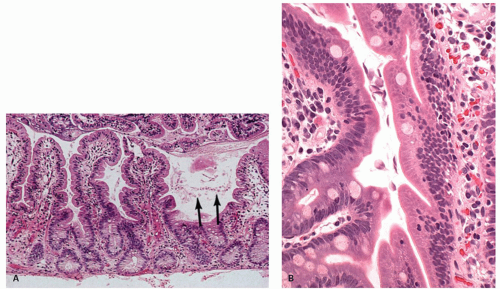

76 Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia may be found in patients with CVID syndromes and selective IgA deficiency (

Fig. 3-15).

Neoplasms The risk of neoplasia developing in immunodeficiency disorders is very high. In the primary immunodeficiency disorders, it has been estimated to be as high at 10,000 times that in the general age-matched population.

87 The GI tract is frequently involved in neoplasia occurring roughly 10 to 200 times that of the general age-matched population (

Table 3-3).

68,

87,

88 The incidence of neoplasia varies with each type of immunodeficiency. The majority of malignancies are of lymphoid or hematopoietic origin (80%), the remainder being epithelial and smooth muscle.

89 However, the type of malignancy varies with the immunologic disorder.

87 Thus, in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, myelogenous leukemia is most common, whereas in common variable and selective IgA deficiency, epithelial tumors and lymphomas occur in approximately equal numbers. The types of neoplasms also vary with age and sex.

88 For example, children with immunodeficiency usually develop non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, whereas in adults, carcinomas and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are found equally often. In ataxia telangiectasia, females develop epithelial malignancies more frequently than males.

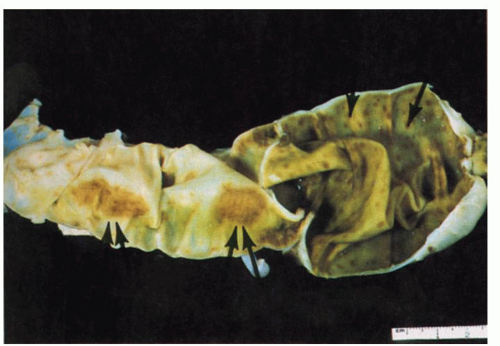

Although neoplasms in the immunodeficiency disorders involve most tissues, primary tumors of the GI tract occur fairly frequently, especially in common variable deficiency.

76,

88 The overall incidence of tumors in one study of CVID was 25% of patients. Approximately half of these tumors occurred in the GI tract and consisted mainly of carcinoma of the stomach and colon or lymphoma (commonly associated with diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia).

87 An increased risk for neoplasia is also found in patients immunosuppressed for transplantation, or following chemotherapy for cancer.

87 The risk of neoplasia in transplant patients is approximately 100 times greater than that observed in the general population in the same age range.

87 In the transplant setting, there is about an equal incidence of developing lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoma (posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, see “Lymphoma” section) and epithelial tumors, and the bowel is involved in approximately 12% of cases.

87 Finally, GI tumors, primarily lymphoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and smooth muscle tumors,

89 can be seen in untreated AIDS patients.