Fig. 5.1

Schematic representation of the current hypotheses on the aetiopathogenesis of IgG4-RD and IAC. (With thanks to WouterSmit (AMC, Amsterdam) for his contribution in illustrating this figure)

Role of Genetic Factors

HLA class II serotypes DRB1*0405 and DQB1*0401 have been associated with increased disease susceptibility in Japan [18]. In contrast, this was not demonstrated in Korea, where disease relapse was associated with aspartic acid substitution at DQβ1-57 [19]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) involved in disease susceptibility or recurrence have been reported to be present within genes encoding cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and Fc receptor-like 3 (FcR-3) [20–23] (Table 5.1). However, most genetic studies have centred on AIP in Asian patients and the applicability of this to other ethnic groups remains uncertain.

Table 5.1

Single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with AIP

Proteins | SNP | Association | References |

|---|---|---|---|

CTLA-4 | 49A haplotype | Higher in AIP in China | Chang et al. [20] |

−318C/+49A/CT60G | Increased susceptibility to AIP in China | Chang et al. [20] | |

+6233 3′-untranslated region | Increased susceptibility to AIP in Japan | Umemura et al. [22] | |

+6230G/G | AIP susceptibility | Umemura et al. [22] | |

+6230A | AIP resistance | ||

49A/A and +6230A/A genotypes | Increase AIP relapse in Japan | ||

TNF-α | 863A haplotype | Extra-pancreatic involvement in China | Chang et al. [20] |

FcR-3 | –110A/A genotype | Increased susceptibility to AIP in Japan (serum IgG4 correlated to susceptible alleles) | Umemura et al. [21] |

Loco-regional Factors

The involvement of the biliary tract, gallbladder and liver in many patients with AIP may suggest loco-regional factor(s) in pathogenesis. Peribiliary glands, which are physiologically distributed around the extrahepatic and intrahepatic large bile ducts [24] may be severely damaged in patients with IAC [25]. These glands are known to contain small amounts of exocrine pancreatic acini [26]. It has been postulated that a common antigen could be expressed in these glands, leading to the spectrum of manifestations observed in the hepato-biliary-pancreatic ductal system.

Helicobacter pylori and Molecular Mimicry

A role for gastric Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of AIP was suggested in 2005 on the basis that H. pylori was associated with other autoimmune disorders and an increased detection of peptic ulcers in patients with AIP [27]. Significant homology between human carbonic anhydrase-II (CA-II) and α-carbonic anhydrase of H. pylori in segments containing the binding motif of the susceptibility HLA molecule DRB1_0405 was demonstrated [28], and the authors proposed that this pathogen may trigger AIP in genetically predisposed individuals by means of molecular mimicry. This hypothesis was supported by the detection of antibodies against plasminogen-binding protein of H. pylori in 94 % of patients in an Italian cohort with AIP [29]. In a recent study, no sequences of H. pylori DNA could be demonstrated in tissue or pancreatic juice from patients with AIP suggesting a direct infection was unlikely [30]. The role of this pathogen remains undetermined.

Autoimmunity and Autoantigens

Several autoantigens have been investigated based on the theory that IgG4-RD is an autoimmune disorder. Non-specific antinuclear antibodies are identified in more than half of patients. Autoantibodies against lactoferrin (LF) and carbonic anhydrase (CA)-II, expressed in exocrine organs including the pancreas, salivary gland, bile duct, and renal tubules, can be detected in 73 and 54 % AIP patients, respectively [31]. A strong positive correlation between increased serum IgG4 levels and anti-CA-II antibody levels has been reported [32]. Anti-CA-IV antibodies, expressed in the epithelial cells of several organs, have also been detected in 34 % of AIP patients [33]. The wide distribution of LF and CA was suggested to provide a unifying explanation for the multisystem involvement in IgG4-RD, but these antibodies are non-specific for the disease. Antibodies against pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI) were detected in 30–40 % of AIP patients [34] and autoantibodies against pancreatic exocrine enzymes and anti-PSTI antibodies were demonstrated by RNA microarray of pancreatic tissue and immunoassays in AIP patients from Europe [35]. In a proteomics study from Japan, a 13.1-kDa protein was identified as a candidate autoantigen, although the sequence has not been determined [36].

Role of IgG4 Molecule

IgG4 is the least common IgG subclass representing less than 5 % of total IgG in the serum [37]. However, it can account for up to 80 % of total IgG after chronic exposure to certain antigens. IgG4 is a unique antibody with important amino acid differences to IgG1 in the CH2 domain resulting in an inability to activate complement via the classical pathway and reduced cellular immune responses due to decreased binding to the Fc-gamma receptors of effector cells [17, 38]. In the core hinge region, an amino acid switch allows IgG4 to undergo exchange of half-antibodies generating functionally monovalent antibodies which cannot cross-link antigens or form large immune complexes. IgG4 can bind the Fc portion of other IgG molecules at its constant domain, contributing to its anti-inflammatory function.

A direct role for IgG4 antibody in the pathogenesis of IgG4-RD has not been confirmed. IgG4 autoantibodies have not been detected in IgG4-RD although they have been shown to play an important role in unrelated immune-mediated disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris [39]. Interestingly, IgG4 in sera from patients with AIP can bind with normal human bile and pancreatic duct epithelia, a reaction that was abolished with steroid therapy [40]. The dense infiltration of the affected tissues with IgG4-positive plasma cells and the elevated levels of serum IgG4 seen in the majority of patients is still unexplained, but may be an epiphenomenon of the disease [10].

Role of Type 2 Helper (Th2) T-Cell Immune Responses

The immune-pathogenesis underlying the prominent lymphoplasmocytic infiltration with abundant IgG4 positive plasma cells in this disease is not fully understood. On immunohistochemistry, both CD20+ B cells and CD4+ T cells are present. In tissue and blood, a Th2 immune response predominates with increased expression of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 [41, 42], unlike other autoimmune disorders such as PSC and PBC where Th1 immune responses result in increased production of IFN-γ [43, 44]. These Th2 responses and related cytokine profile may explain some of the findings in IAC including the elevated serum IgE level, peripheral and tissue eosinophilia seen in some patients [45]. A role for Th2 cytokines in the bile of IAC patients in disrupting the biliary epithelial cell barrier function leading to chronic biliary inflammation in these patients has also been proposed [42]. There is a well-known association of Th2 responses with allergic disorders, and a history of allergy reported in over half of patients with AIP, although an allergic trigger has not been demonstrated so far.

Role of T Regulatory Cells (Tregs)

Inducible-memory T regulatory cells (Tregs) and their regulatory cytokines were found to be up-regulated in both peripheral blood [46] and the affected tissues [41] of AIP and IAC patients. The reasons for this are not completely understood. Tregs are well known to play an important role in prevention of autoimmune disorders [47] and the attenuation of immune reactions associated with allergic and infectious disorders [48] by producing the regulatory cytokines IL-10 and tumour growth factor-b (TGF-b). The up-regulation of Tregs in IAC and AIP, therefore, may represent a secondary reaction to the excessive Th2 responses. It has been demonstrated previously that IL-10 can induce B cells to isotype switch to produce IgG4 [49] and that TGF-b is an important cytokine involved in tissue fibrogenesis. Therefore, the up-regulation of these two regulatory cytokines may mediate the two major histological manifestations of IgG4-RDs, i.e. infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells in affected tissues and storiform fibrosis.

Epidemiology and Demographics

Epidemiological data on the prevalence of IAC is scarce due to the lack of population-based studies. Most studies come from Japan and focus mainly on AIP. The estimated prevalence of AIP was reported to be 0.8 cases per 100,000 persons in Japan and the incidence was estimated to be 0.28–1.08/100,000, with approximately 336–1300 new cases per year [6]. Around 74 % of AIP patients are reported to have a concomitant IAC whereas isolated IAC is seen only in 8 % of cases [50]. Therefore, the prevalence of IAC may be estimated to be around three quarters that of AIP. Approximately 10 % of patients originally diagnosed with “sclerosing cholangitis” will have steroid-responsive strictures of the biliary tract with lymphoplasmocyticinfiltrates and IgG4-positive plasma cells in their bile ducts histology—these patients most likely have IAC rather than PSC, although diagnostic criteria should be adhered to when making this diagnosis [51].

The prevalence of IAC among patients diagnosed as PSC was evaluated by some previous studies that reported that approximately 7–9 % of patients presenting as PSC have features of IAC [52, 53]. In the largest two series of patients reported from Mayo Clinic [50] and King’s College in London [2], the majority of patients were adults, male and typically older than 50 years.

Clinical Features

Clinical Manifestations

The spectrum of clinical manifestations in IAC is highly variable. Compared to classical PSC [54], 75 % of IAC patients present abruptly with obstructive jaundice [14]. The pancreas is involved in more than 90 % of IAC patients, therefore manifestations of pancreatic insufficiency including anorexia, weight loss, steatorrhoea and new-onset diabetes mellitus are often present [1, 4, 14]. Other common symptoms may include abdominal pain, pruritus, pancreatitis, and cholestatic biochemistry [50]. IAC patients may also present with a pancreatic mass, common bile duct/hilar strictures or hepatic mass mimicking pancreatic cancer, CCA and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) respectively. Differentiating AIP and IAC from these malignancies is impossible based on symptoms alone and can result in inappropriate major surgical interventions unless considered early and excluded [2, 4].

Laboratory Findings

Around 90 % of patients with IAC have elevated serum alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltransferase levels at diagnosis. Serum bilirubin levels are usually higher compared to classical PSC patients, particularly in those presenting with obstructive jaundice [38, 55].

Hypergammaglobulinemia is common [55–58], however, it is usually caused by the significantly higher IgG4 levels compared to PSC patients where IgG1 is predominant [55]. Markedly raised IgG4 levels >2.8 g/L (twice the upper limit of normal) are more suggestive of IAC and >5.6 g/L (four times the upper limit of normal) are highly specific for IAC, whereas moderately raised levels >1.4–2.8 g/L can be seen in otherwise classical PSC [53], cholangiocarcinoma [59], pancreatic cancer [60] and other inflammatory and infective disorders. Furthermore, serum IgG4 levels >1.4 g/L can be seen in 5 % of healthy individuals. IgG4 levels can be normal in almost 20 % of patients at diagnosis [58] and can define a milder clinical phenotype with lower risk of relapse and fewer organs involved. Specificity and sensitivity of 97 and 50 % for IAC, respectively, were obtained using IgG4 levels >2.8 g/L [59]. Specificity and sensitivity of 100 and 26 %, respectively, using a cut-off of IgG4 >5.6 g/L was reported [59]. Therefore a very high serum IgG4 is highly specific for IAC but below a cut-off of 5.6 g/L there are limitations to differentiate from other disease mimics. The utility of biliary IgG4 levels for IAC was recently explored in a single small study which showed promise but needs further clarification [61]. The use of ratios such as the IgG4-positive plasma cell/mononuclear cell ratio was found to be significantly higher in IAC than PSC and needs extended studies [62].

ANAs and other disease non-specific autoantibodies, eosinophilia, and/or elevated IgE levels might be seen in around 20–40 % of IAC cases but are non-specific. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA), which are frequently detected in PSC, are usually absent in IAC. Tumour markers are also not specific to distinguish IAC from malignancy, with high serum Ca19-9 observed in IAC (63 % in one study) [56, 58] and normal or minimally elevated CEA levels in most IAC patients [58].

Cholangiography and Imaging Features

The spectrum of radiological features in IAC is variable and nonspecific. As only a few cases present with isolated biliary disease, pancreatic disease is usually evident on imaging. Dynamic computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may show diffuse enlargement of the pancreas or a focal lesion that mimics pancreatic cancer [63] (Fig. 5.2). Other less commonly described findings include acute pancreatitis, pancreatic atrophy and diffuse enhancement [50] (Fig. 5.3). Although the ability of MRCP to delineate abnormalities of the main pancreatic duct is limited as compared to retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in almost half of patients with diffuse type AIP [64], it continues to be a valuable non-invasive tool for the detection of pancreatic gland abnormalities as well as for follow-up of patients with IAC/AIP. Hilar space-occupying lesions or hepatic mass-like lesions mimicking CCA and HCC, respectively, are among other possible findings.

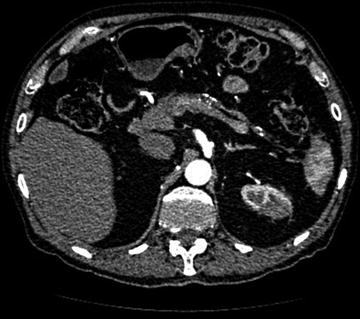

Fig. 5.2

CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast showing a mass at the head of the pancreas obstructing the distal common bile duct with proximal intra hepatic duct dilatation and mild pancreatic duct dilatation

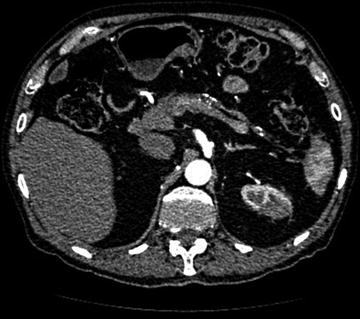

Fig. 5.3

CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast showing an atrophic pancreas in a patient with AIP and IAC. Bile duct resection with Roux en Y anastomosis for recurrent cholangitis originally diagnosed as PSC

Strictures, wall thickening or both are the most frequently reported radiological abnormalities in patients with IAC. Circular and symmetrical thickening of the bile duct wall, smooth outer and inner margins, and a homogenous internal echo can be demonstrated on abdominal ultrasonography (US) [65], CT [66], MRCP, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS). Interestingly, these features can be demonstrated in both stenotic and non-stenotic areas as well as in the gallbladder wall.

The distribution of the radiological changes in IAC is variable. Although a distal common bile duct (CBD) stricture is classical (Fig. 5.4), the involvement of both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts is evident in approximately 50 % of patients [55, 67] (Fig. 5.5). Inflammation and/or edema of the pancreas may contribute to the stricture; however, thickening of the bile duct itself can usually be demonstrated [68]. MRCP is helpful for delineating the distribution and the extent of the strictures; nevertheless, direct assessment by ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography is usually indicated. Advantages of ECRP in this regard relate to its better sensitivity for the detection of subtle changes in the biliary tree and the main pancreatic duct as well as its therapeutic implications including obtaining brushings and biopsies for histopathology assessment and temporary stent insertion to relieve obstructive jaundice or cholangitis [38, 64]. EUS has a role to obtain fine needle aspirates (FNA) to exclude dysplasia and biopsy of a mass where possible.

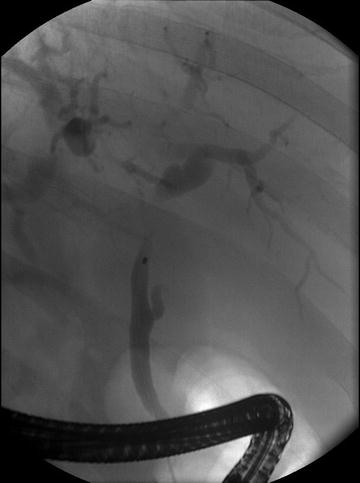

Fig. 5.4

ERCP showing a common hepatic duct stricture with distal right and left hepatic duct dilatation in a patient with isolated IAC. Stent was placed into the left hepatic duct system. This patient had a normal serum IgG4 and proceeded to hepatic resection for presumed cholangiocarcinoma. Resection confirmed classical changes of IAC

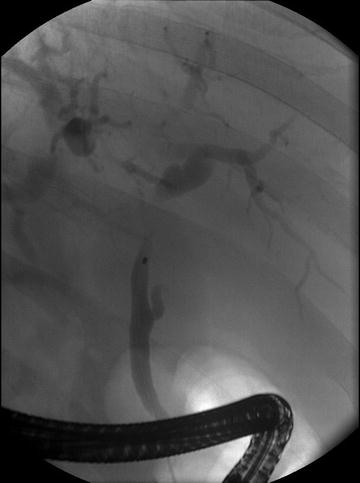

Fig. 5.5

MRCP showing diffuse intrahepatic duct irregularities of IAC with an extrahepatic duct stricture. This patient was originally diagnosed with PSC. Biopsy of the liver and bile duct confirmed IAC and response to corticosteroids was seen

Due to “similar” cholangiography findings, IAC was thought once to represent a PSC variant. There are however subtle differences on imaging [69]. Segmental strictures, long strictures with pre-stenotic dilatation and strictures of the distal common bile duct are typically seen in IAC whereas band-like strictures, beading, pruned-tree appearance and diverticulum-like out-pouching are more typical of classical PSC. Recently, Japanese investigators proposed a cholangiography-based classification for IAC [70]. According to this IAC can be classified into four types. IAC Type 1 is characterised by an isolated distal CBD stricture with chronic pancreatitis—pancreatic cancer and CCA being the most relevant differential diagnosis, which can be distinguished by IDUS [71], EUS-FNA [72] and/or biopsy of the bile duct [7, 71]. In IAC type 2, both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts are involved and it must be differentiated from PSC. Based on the presence or absence of pre-stenotic dilatation with the intrahepatic strictures, this type is further subdivided into Type 2a and 2b respectively. The significance of these subtypes is unclear; however, Type 2b is thought to result from marked lymphoplasmocytic infiltration into the peripheral bile ducts. IAC Type 3 is characterised by hilar and distal CBD strictures whereas Type 4 shows only hilar strictures and both should be distinguished from CCA by means of EUS, IDUS, cytology and/or biopsy of the bile duct. It must be mentioned, however, that the cholangiography findings in some patients with IAC do not fit into any of these four types and the clinical utility of this approach has not been validated.

Histopathology Features

Although the microanatomy of the affected organs and probably the age of the lesions may cause some variability, the histological findings in IAC are generally similar to those seen in other organs involved in IgG4-RD. The large bile ducts are usually affected; however, changes in the small intrahepatic bile ducts can be occasionally demonstrated on liver biopsy.

Histopathological Characteristics of Large Duct Disease

Extrahepatic, hilar and perihilar bile ducts, and also frequently the gallbladder are involved in IAC [12, 14, 50]. Macroscopically, resected bile ducts appear diffusely thickened leading to a “pipe-stem” fibrosis like appearance. Mucosal surfaces are usually normal. Occasionally, periductal inflammatory mass lesions in the resected hilar and perihilar ducts can be seen [73]. The classical findings of IAC on histology include a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, storiform fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis. The combination of these findings coupled with the presence of a significant number of IgG4-positive plasma cells (>10 IgG4-positive plasma cells per mean of three high-power fields (hpf) on biopsy and >50 IgG4-positive plasma cells per mean of three hpf on surgical resection) and an IgG4/IgG ratio of over 40 % is strongly suggestive of IAC in the correct clinical context.

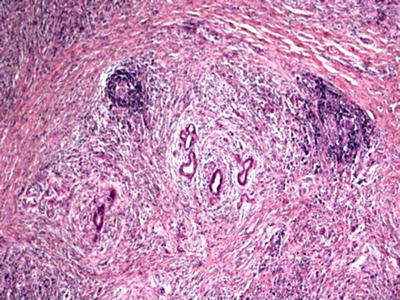

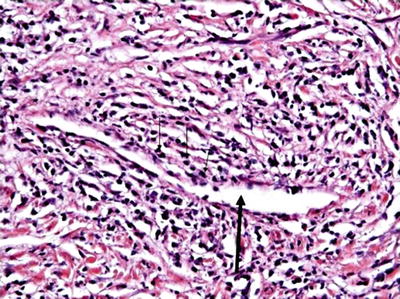

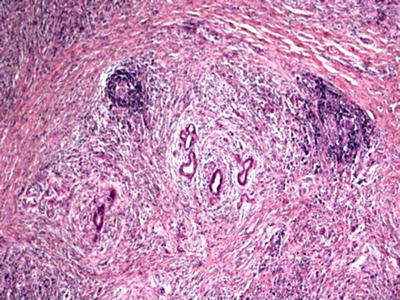

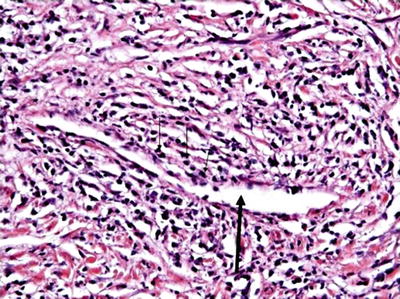

The lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates consist of evenly distributed lymphocytes that often organise into lymphoid aggregates with occasional germinal centres (Fig. 5.6). T-Cells usually predominate, with scattered aggregates of B-cells. Plasma cells are an essential component and may predominate the cellular infiltrates. These cells are polyclonal, in fact a clonal population of plasma cells is sufficient to exclude IgG4-RD. A few macrophages, histocytes and moderate tissue eosinophilia is not uncommon [2, 12, 74]. The inflammatory process is intermingled with a unique storiform pattern of fibrosis that resembles the spokes of a cartwheel with spindle cells radiating from a centre. Compared to PSC, the biliary epithelium appears normal, unless a biliary stent is present. The fibro-inflammatory process usually extends to the peribiliary adventitial veins, nerves and glands [12]. Obliterative phlebitis results from obliteration of adventitial venous channels within the dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates (Fig. 5.7). Lymphocytes and plasma cells can be seen within the wall and the lumen of the veins. Occasionally, the obliteration can be partial. Arteritis is not a usual finding, although its presence does not exclude the diagnosis. The inflammatory process involving the hilar/perihilar region is largely confined to the portal tracts, with only minimal extension into the adjacent liver parenchyma [2, 12, 74].

Fig. 5.6

Histology (H and E) from a bile duct resection demonstrating a lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltrate with peri-ductal distribution and a storiform fibrosis

Fig. 5.7

Histology (H and E) showing obliterative phlebitis

Although not entirely specific, demonstration of IgG4-positive plasma cells on immunohistochemistry is important for diagnosis. However, these cells have been also demonstrated in a number of other disorders [2, 74]. The number of IgG4-positive plasma cells in IAC and other IgG4-RDs, however, has been shown in multiple studies to be significantly higher than other disorders. The exact cutoff of IgG4-positive plasma cells with which the diagnosis can be made with high confidence is controversial. It varies between organs and depending on the presence of fibrosis. A recent consensus statement proposed that >50/HPF in surgical specimens and >10/HPF in biopsy samples are required for diagnosis of IAC [75]. It should be remembered, however, that these cutoffs are not essential for the diagnosis, as fewer cells can be seen in some patients with long standing fibrotic disease [75] (Fig. 5.8). IgG4/IgG cell counts ratio >40 % was found to be particularly helpful in discriminating IgG4-RD from other disorders with moderate number of IgG4-positive plasma cells [74, 75]. Nevertheless, this ratio itself is not sufficient to establish the diagnosis and should be interpreted in conjunction with other clinical, radiological, serology and histopathology findings [75].

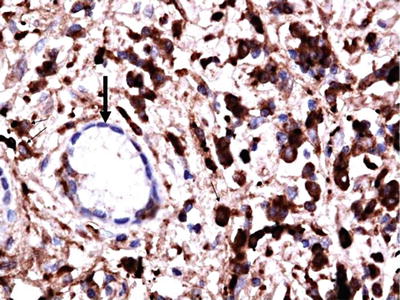

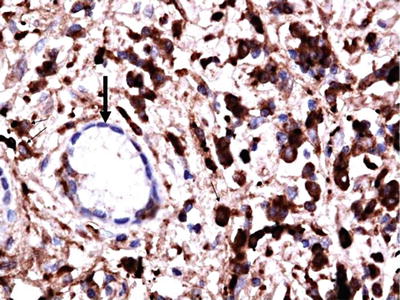

Fig. 5.8

Immunostaining of the bile duct showing IgG4-positive plasma cells >10/HPF (dark brown)

Histopathology Findings of Small Duct Lesions

Although frequently variable and inconclusive, small bile duct involvement can be demonstrated on liver biopsy [76]. The spectrum of possible histological changes includes sclerotic changes with dense periportal fibrosis, marked portal inflammation with many plasma cells, ductular reaction, lobular inflammation and canalicular cholestasis [76]. Characteristic features like obliterative phlebitis can be demonstrated when a medium-sized portal vein is present in the specimen obtained. More than 10/HPF IgG4-positive plasma cells (20 % of biopsy samples) [76–78] and small inflammatory nodules in peripheral portal tracts that are composed of spindle cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils are specific findings for IAC [77, 78]. Ductopaenia and periductal fibrosis, typically seen in PSC, argues strongly against IAC [76–78].

Diagnosis

There is no pathognomonic feature of IAC. Common features seen in IAC such as pancreatic duct abnormalities (7–15 %), increased serum IgG4 (9–36 %) and IgG4-positive plasma cells (23 %) were reported to occur also in patients with PSC and other disorders [3]. Therefore, IAC diagnosis must be based on a combination of clinical, serologic, imaging, and histologic findings [4]. Multiple diagnostic criteria have been proposed in order to distinguish IAC from other conditions that may share similar features. The HISORt (histology, imaging, serology, other organ involvement and response to corticosteroid) criteria for AIP [63] and its IAC version [50] (Table 5.2), Asian consensus criteria [79] and most recently new Japanese criteria [80] (Table 5.3) are the most widely applied. Although these criteria share almost the same diagnostic items, the combination of criteria required to establish a definite diagnosis is variable. For example, a definite diagnosis can be established in the presence of either typical histology from a previous resection or biopsy or classic imaging of AIP/IAC with increased serum IgG4 levels according to the HISORtcriteria [50]. In patients who have do not meet these criteria and have a high index of suspicion, every effort should be made to rule out malignancy. This is followed by a re-evaluation after 4 weeks of corticosteroids therapy and if a response is observed the diagnosis of IAC can be confirmed. In contrast, response to steroids is considered as an optional criterion by the Asian and Japanese criteria and its presence cannot establish a definite diagnosis in the absence of other criteria that are considered crucial for definite diagnosis [79, 80].

Table 5.2

The HISORt criteria for IAC [50]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree