Category

Description

Japanese viewpoint

Category 1

Negative for neoplasia/dysplasia

a

Category 2

Indefinite for neoplasia/dysplasia

a

Category 3

Non-invasive low-grade neoplasia (low-grade adenoma/dysplasia)

a

Category 4

Non-invasive high-grade neoplasia

4.1 High-grade adenoma/dysplasia

Non-invasive carcinomac

4.2 Non-invasive carcinoma (carcinoma in situ)b

4.3 Suspicion of invasive carcinoma

a

Category 5

Invasive neoplasia

5.1 Intramucosal carcinomad

a

5.2 Submucosal carcinoma or beyond

a

Criteria of atypia | Normal | Adenoma | Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Low grade | High grade | ||||

Cellular atypia | Nuclear size (μm) | 4.5 × 1.5 |  | ≤20 × 10 | |

Chromatin (blue-violet) | Dotted |  | Coarse, bright | ||

Nuclear polarity | Basal |  | Nonpolarised | ||

Nucleus/gland ratio | Low |  | High | ||

Nucleus/cell ratio | 0.15–0.3 |  | 0.5–0.9 | ||

Structural atypia | Glandular structure | Tubular | Tubular/villous ± branching | Tubulovillous, ± snaking, branching | Tubulovillous and cribriform |

Index of structural atypia | Normal |  Increased Increased | |||

2.1.1.2 Malignant Potential

The likelihood of nodal metastasis mainly depends on histologic grading and depth of submucosal invasion of any T1 carcinoma as well as on macroscopic type and anatomical localisation in the gastrointestinal tract.

Well-differentiated mucosal cancer shows a relatively structured and continuous infiltrative growth pattern of glandular crowding, branching, and budding with clear histologic borders to normal localised tissue being reflected by clear endoscopic margins of the neoplasia. Relative loss of polar structure of epithelial cell layers, enhanced nucleus/cytoplasm ratio, and bulky growth of epithelial cell layer in the neoplasm (as compared to normal epithelium and mucosa) alter the surface aspect of mucosal neoplasias – inducing a mucosal pattern most often visible on IEE. In case of massive submucosal invasion of coherently growing carcinoma, the surface gland structure (typical for differentiated mucosal cancer) becomes destroyed – yielding highly irregular or even non-structured surface (amorphous pattern) on stereomicroscopic observation as well as on IEE. In addition, differentiated mucosal cancers require neoangiogenesis for deep submucosal invasion – showing on IEE irregular microvessels in mucosal proper layer as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry in resected early cancers and correlated with imaging features on IEE [1, 3, 5, 14].

Likelihood of lymph node metastasis generally increases with depth of invasion of well-differentiated early cancer [2, 3, 15]. The best data on these correlations have been collected in large surgical series of resected early cancers with dissection of regional lymph nodes [2, 15–21], as summarised in Table 2.3. To predict risk of metastasis to locoregional lymph nodes for well-differentiated early cancers, T1 lesions of the colon are categorised into “low risk”, i.e. grading G1 or G2, no invasion of lymphatic vessels (L0) or submucosal veins (V0), and submucosal extension of less than 1,000 μm, vs. “high risk” in the presence of any feature like tumour budding (isolated tumour cells at the invasive tumour front), submucosal invasion ≥1,000 μm, lymphatic or venous vascular invasion, or grading G3 or G4 [15].

Table 2.3

Probability of lymph node metastasis of superficial cancers by extent of submucosal invasion (μm)

Carcinoma | Depth of invasion | LN pos. cases (%) |

|---|---|---|

SCC (type 0–II; grading G1, G2) | m1 | 0 % |

if L0, V0, d <5 cm, no ulcer, cN0 | m3 (muscularis mucosae) | 8 % |

sm1 (<200 μm and d <5 cm) | 4.2 % | |

Overall | sm1 (<200 μm) | 17 % |

AC (CLE Barrett’s) | pT1m | 1.9 % (CI 1.2–2.7 %) |

pT1sm | 21 % | |

AC intestinal type G1–G2 | pT1m (d <30 mm) | 0 % (CI 0–0.3 %) |

pT1sm1 (<500 μm) | 0 % (CI 0–2.5 %) | |

AC undifferentiated G3–G4 | pT1m (d <20 mm, no ulcer) | <1 % (CI 0–2.6 %) |

AC type 0–II | pT1 (sm <1,000 μm) | 1.4 % (0–5 %) |

AC type Ip | pT1 (Ip-head, sm < 3,000 μm) | 0 % |

The macroscopic type (Paris classification, Fig. 4.2) is another indicator of risk of lymphatic and/or vascular spread of early cancer [1–4, 15], probably reflecting heterogenous morphogenic and molecular pathways of oncogenesis (compare Sect. 2.2 on pathways of colonic carcinogenesis).

Poorly or undifferentiated early cancers (G3/G4) show loss of cell–cell adhesion, discontinuous growth pattern, high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio paralleled by more rapid tumour cell replication/proliferation, and higher metastatic potential (e.g. anoikis) on a cell biology level. Therefore, lymphatic vessel or blood vessel permeation is frequent with even small, poorly differentiated intraepithelial early cancer, and so are higher rates of lymph node (or haematogenous) metastases as compared with well-differentiated mucosal cancer [2, 15, 17]. The risk of metastatic spread to locoregional lymph nodes is increased for poorly differentiated early gastric cancer exceeding lateral extension of 20 mm [2, 17]. Also, margins of undifferentiated mucosal cancers tend to be less clear, the epithelial surface structure in the central part of the cancer may be destroyed by epithelial invasion with undifferentiated cancer cells, and the microcapillary pattern in the lamina propria mucosae tends to be very irregular on magnifying NBI endoscopy.

Based on extensive quantitative histopathologic analysis of surgical resection specimens of early gastrointestinal cancers, the likelihood of cure from early cancer achievable by endoscopic en bloc resection with free margins can now be predicted on based histologic characteristics, lateral size, depth of submucosal invasion, absence of lymphovascular invasion, and organ location in the GI tract (Table 2.4 Criteria of curative resection). Magnifying endoscopic analysis of early cancers attempts to predict from characteristic alterations of the macroscopic type, surface and microvascular structure, whether the lesion allows endoscopic resection en bloc for cure (Indication criteria, see Chaps. 3 and 6–10).

Table 2.4

Criteria of curative endoscopic resection in oesophagus, stomach, and colorectum

Organ | Criteria of curative resection en bloc |

|---|---|

A. Stomach | 1. Guideline criteria |

m-ca, diff. type, ly (−), v (−), Ul (−), and ≤2 cm in size | |

2. Expanded criteria | |

m-ca, diff. type, ly (−), v (−), Ul (−), and any size >2 cm | |

m-ca, diff. type, ly (−), v (−), Ul (+), and ≤3 cm in size | |

sm 1-ca (invasion depth <500 μm), diff. type, ly (−), v (−) | |

m-ca, undifferentiated type (G3), ly (−), v (−), Ul (−), and size <2 cm | |

B. Oesophagus (squamous lesions only) | 1. Guideline criteria |

1) pT1a-EP-ca, 2) pT1a-LPM-ca | |

2. Expanded criteria | |

pT1a-MM-ca, ly (−), v (−), diff. type, expansive growth, ly (−), v (−) | |

cT1b/sm-ca (invasion depth <200 μm), ly (−), v (−), infiltrative growth pattern, expansive, diff. type, ly (−), v (−) | |

C. Colorectum | 1. Guideline criteria |

m-ca, diff. type, ly (−), v (−) | |

sm-ca (<1,000 μm), diff. type, ly (−), v (−) |

2.2 Characteristics of Colonic Neoplastic Lesions

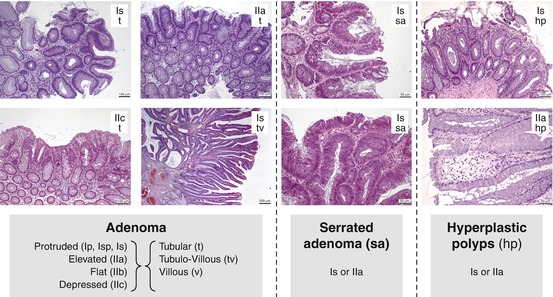

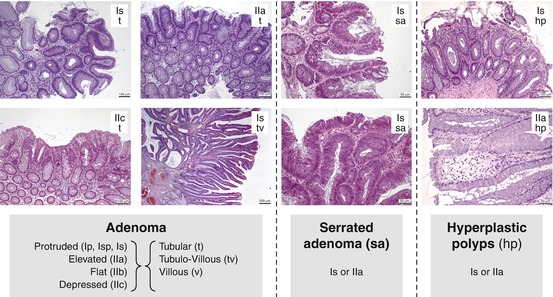

On colonoscopy, most protruded or flat lesions classify as adenomatous or hyperplastic according to histomorphology – see Fig. 2.1. Whereas strictly hyperplastic lesions are non-neoplastic, the similarly looking serrated adenomas are – like polypoid adenomas – cancer precursor lesions.

Fig. 2.1

Principles of histomorphology of adenomatous or hyperplastic mucosal lesions in the colon

The usual perception of morphological carcinogenesis still focusses on the classical “polyp–cancer sequence” [23], although at least four other precursor–cancer pathways exist in the colon – the depressed neoplasia pathway, non-polyposis (HNPCC) pathway, serrated adenoma pathway, and in ulcerative colitis and in colitis Crohn the “inflammation–dysplasia (DALM)–carcinoma pathway” [1, 4, 7, 23–27] (Table 2.5).

Table 2.5

Morphogenic pathways of colorectal carcinogenesis

Superficial neoplasms | CRC risk estimates | Precursors of CRC (estimated) |

|---|---|---|

1. Classical adenoma | ||

Polypoid (type 0–Ip,s) | ||

Distal > proximal | 10 years | |

CIN (LoH, kRAS, APC) | 15–30 % | 60 % |

2. Serrated adenoma | ||

Serrated polyp (kRAS), distal | 5 years | |

Sessile SA (BRAF), proximal | 60 % | ~10 % |

CIN (kRAS) | ||

MSI+++ (BRAF, CIMP) | ||

3. Depressed NpI 0–IIc | 1–< 5 years | 25–30 % |

“De novo cancer” | 75 % | |

Proximal > distal | ||

MSI+++ | ||

4. HNPCC adenoma | ||

Flat adenoma 0–IIa/b/c | 1–5 years | ~5 % |

Proximal (70 %) > total colon | 40–80 % | |

MSI+++ (MLH mut, CIMP) |

2.2.1 Classical Polypoid Adenoma–Carcinoma Pathway

Polyps have been snared in the colon since 1972, and histologic observations led to the polypous adenoma–dysplasia–cancer sequence [29] that had been translated into molecular pathways of oncogenesis by Vogelstein et al. [23]. In addition, screening colonoscopy with clearing of all detectable adenomas by endoscopic polypectomy had reduced the incidence of CRC far below predicted rates [30]. This served as rationale for the approval of colonoscopy screening to prevent CRC in the USA and many Western countries. From an endoscopic vantage point, Kudo et al. [4] and Uraoka et al. [31] described a separate entity – superficially spreading adenomas of more than 10 mm diameter – as lateral spreading type neoplasias (LST) which require an ablative strategy of its own.

2.2.2 Flat/Depressed Colonic Adenoma–Carcinoma Pathway

The majority of advanced CRC may develop from a non-polypoid precursor lesion [1, 4, 32, 33]. In the “depressed neoplasia–carcinoma sequence”, minute “de novo” cancers of 2–5 mm size, most with submucosal invasion, have been described by Shimoda et al. [33]. In more than 1,000 colonic neoplasms, they diagnosed 71 cancers, and 78 % of these originated from non-polypoid precursor lesions and 22 % from polypoid adenomas. Ten of 75 cancers were minute (<5 mm) depressed-type cancers without adenomatous areas, but all of them with submucosal invasion. Depressed-type (0–IIc) colorectal carcinomas are at a more advanced stage than non-depressed lesions (0–IIa or b) [4, 6]. Therefore, these depressed-type neoplasms have a high likelihood of malignant progression and tend to show shorter evolution time to cancer.

2.2.3 Serrated Adenoma–Carcinoma Pathway

Sessile serrated adenomas show the endoscopic appearance and pit pattern (type II) of hyperplastic polyps, whereas polypoid (i.e. “traditional”) serrated adenomas mainly exhibit adenomatous pit pattern (pp IIIL or IV) [26, 32]. However, these lesions are premalignant via the “serrated pathway” to adenocarcinoma [7, 25, 26, 32, 34]. About 8 % of all and 18 % of proximal colorectal carcinomas originate from the “serrated pathway” involving the sequence hyperplastic aberrant crypt foci → hyperplastic polyps (HP) or sessile/polypoid serrated adenomas (SSA/TSA) → admixed polyps (serrated adenoma with dysplastic focus) → cancer [32]. Sessile serrated adenomas are located mainly in the proximal colon, traditional polypoid serrated adenomas more often (>60 %) in the left hemicolon [26, 32]. Serrated adenomas show about twice as frequent malignant transition than classical polypoid adenomas. On a molecular basis, serrated polyps are the precursors of type 1-CRC (CIMP-high/MSI-high/BRAF mutation) and type 2-CRC (CIMP-high/MSI-low/MSS/BRAF mutation) [7, 35].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree