1. Germ cell tumours

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia, unclassified type (IGCNU)

Seminoma (including cases with syncytiotrophoblastic cells)

Spermatocytic seminoma (mention if there is sarcomatous component)

Embryonal carcinoma

Yolk sac tumour

Choriocarcinoma

Teratoma (mature, immature, with malignant component)

Tumours with more than one histological type (specify percentage of individual components)

2. Sex cord/gonadal stromal tumours

Leydig cell tumour

Malignant Leydig cell tumour

Sertoli cell tumour: lipid-rich variant, sclerosing and large cell calcifying

Malignant Sertoli cell tumour

Granulosa cell tumour: adult type and juvenile type

Thecoma/fibroma group of tumours

Other sex cord/gonadal stromal tumours: incompletely differentiated and mixed

Tumours containing germ cell and sex cord/gonadal stromal (gonadoblastoma)

3. Miscellaneous non-specific stromal tumours

Ovarian epithelial tumours

Tumours of the collecting ducts and rete testis

Tumours (benign and malignant) of non-specific stroma

18.1 GCTs

18.1.1 Intratubular Germ Cell Neoplasia (ITGCN)

ITGCN or carcinoma in situ of the testis (CIS) is a non-invasive pre-malignant lesion. It is the precursor of all testicular germ cell tumours with the exception of spermatocytic seminoma. It is thought to derive from primordial germ cells. When discovered in an adult testis, it is believed to have been present since birth. CIS is found in testicular tissue adjacent to testicular GCTs in about 90 % of cases, and it is also observed in the contralateral “normal” testis of 5–10 % of patients with testicular cancer [6, 7]. It may also occur in patients with cryptorchidism, infertility, atrophic testis (36 %) and intersex. Conversely, CIS is found in less than 1 % of the normal male population. If left untreated, this condition is associated with a 50 % risk of developing GCT within 5 years and a 70 % risk within 7 years [6, 8, 9]. Although it is not a routine practice in many centres, expert panels advocate contralateral testicular biopsy to rule out ITGCN in high risk patients: age <40 years, history of undescended testis, testicular volume <12 ml, presence of grade 3 microlithiasis (see details later in radiological procedures) [10]. The trans–scrotal approach is prohibited and an open inguinal biopsy in unanimously recommended [10, 11].

18.1.2 Seminoma

Seminoma is the most common type of GCT and occurs at an older average age than NSGCTs. Indeed most cases are diagnosed in the fourth or fifth decade of life. The majority of GCT found in the undescended testis is seminomas [2]. It has been suggested that seminomas are the common precursor for other NSGCT subtypes [12].

Two types of seminomas are described: the typical (classic) and spermatocytic seminoma. The expression “anaplastic seminoma” is now considered obsolete. It was used in the past to refer to a seminoma with high mitotic activity but was not found to influence the treatment since there are no poor prognostic groups for seminomas (see later).

Classic seminoma: This forms 40 % of GCTs (Fig. 18.1). Histologically, it is made of clear cells resembling primitive germ cells. Its incidence has doubled during the last 30 years. It mostly affects young men aged 20–55 years. At presentation, 75 % of classic seminomas are limited to the testes, 20 % have retroperitoneal extension and the remaining 5 % have supradiaphragmatic and/or visceral metastases. There is an increased serum placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) in 33–91 % and an increased beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (βHCG) in 5 % of cases.

Fig. 18.1

Gross specimen of a radical orchiectomy showing a seminoma with areas of necrosis (Courtesy of A. Durlach, Pol Bouin Laboratory, University Hospital of Reims, France)

Spermatocytic seminoma is rare and accounts for 1–4 % of GCTs. The expression spermatocytic seminoma appears to be a misnomer since this clinicopathological entity is completely distinct from other GCTs. Spermatocytic seminoma has several specific characteristics which differ from other GCTs: It lacks ITGCN and is not associated with a history of cryptorchidism nor bilaterality. Furthermore, it has no ovarian homologue and is not associated with increase serum markers. It does not express PLAP, OCT3/4 (octamer-binding transcription factors), or i(12p), and it is never found as part of mixed GCTs [13]. It usually presents in older age groups with a peak incidence in the sixth decade (median age: 55 years). It is considered a benign tumour as it virtually never metastasizes and is completely cured by orchiectomy [13–15]. The cell size varies from that of a lymphocyte to that of a giant cell (100 μm). Following the discovery of polypoid populations of tumour cells in spermatocytic seminoma, it has been speculated that this tumour results from self-fertilization of germ cells [16]. This hypothesis may also explain why this pathological entity never occurs in the ovary. For all the above-mentioned reasons, some authors have suggested not to consider spermatocytic seminoma as a variant of seminoma [14]. Exceptional cases of a histological “transformation” of spermatocytic seminoma into testicular sarcoma have been reported with a high mortality rate within 2 years [17].

18.1.3 NSGCT

Embryonal carcinoma (EC) occurs in a population estimated to be 10 years younger than that of the seminoma and comprises 2–3 % of GCT. Its cells are undifferentiated with crowded pleomorphic nuclei and resemble primitive epithelial cells from early-stage embryos [13]. EC is the second most aggressive GCT after choriocarcinoma and is associated with a high rate of metastasis, often with normal serum tumour markers [2]. EC is the most undifferentiated cell type of NSGCT and has a totipotent capacity, i.e. is able to differentiate into other NSGCTs cell types. This differentiation capacity may be expressed in the primary tumour or in metastatic sites and would explain why a teratoma or other histological types may be identified in distant sites, while the primary type is an embryonal carcinoma. It was shown that 74 % of patients had nodal disease at presentation and half of these have also distant metastases [18].

Choriocarcinoma (CC): Testicular CC is a rare and aggressive tumour with a very poor prognosis affecting mostly young subjects aged 25–30 years. Pure CC comprises only 0.3–0.5 % of GCT. Mixed forms with a CC component are more frequent (8–16 % of GCT); however, a combination with spermatocytic seminoma or mature teratoma does not exist. The majority of patients at diagnosis have an advanced stage of the disease. CC may present with a disseminated form even if the primary lesion is small and it spreads by hematogenous routes commonly to lungs, liver, gastrointestinal tract, adrenals and brain including the possibility of eye and skin metastases [19, 20]. Histologically it contains cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts, the latter being responsible for the production of βHCG which is characteristically very elevated (>100,000 IU/L) in these tumours [21]. Metastatic CCs are prone to bleed, either spontaneously in a rapidly progressive advanced disease or immediately after initiation of chemotherapy. This bleeding can be catastrophic and fatal, particularly when it occurs in the lungs or brain [22]. Autopsy performed in patients who have died from this disease has revealed lung, liver and gastrointestinal metastases in 100, 86 and 71 % of cases respectively, while spleen, brain and adrenal metastases were encountered in 56 % [23].

Yolk sac tumour is also called endodermal sinus tumour and is the most common type of testicular GCT in the paediatric group below 15 years. It is also commonly found as a component in the primary mediastinal mixed GCTs. Schiller-Duval bodies, embryonal bodies and hyaline globules may be seen in the yolk sac histology. They almost always produce AFP (90 %) but not HCG. 10–20 % are metastatic at presentation by lymphatic or hematogenous spread.

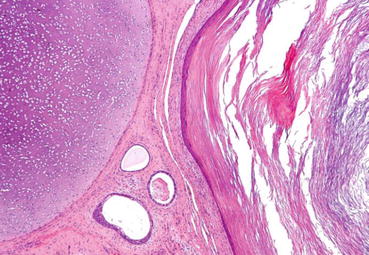

Teratoma, from the Greek words teratos (monster) and oma (tumour), was coined by Rudolf Virchow in 1863 to this “strange” and “monstrous tumour” because of its gross appearance and its odd contents consisting of hair, bone, cartilage or teeth [24]. Teratoma may be cystic or solid and contains all three germ cell layers in different stages of maturation. These are endoderm (GI, respiratory), mesoderm (bone, muscle, cartilage) and ectoderm (squamous epithelium, neural tissue) (Fig. 18.2). Well-differentiated tumours are labelled mature teratomas, whereas the incompletely differentiated (i.e. similar to foetal or embryonal tissue) are called immature teratomas. Mature teratomas may include elements of mature bone, cartilage, tooth or hair. They generally have normal tumour markers. Paediatric teratomas are benign and occur at a median age of 20 months.

Fig. 18.2

Micrograph of a teratoma showing tissue from all three germ layers: mesoderm (immature cartilage – left-upper corner of image), endoderm (gastrointestinal glands – centre-bottom of image) and ectoderm (epidermis – right of image). H&E stain. CC BY-SA 3.0 (free of copy and share)< div class='tao-gold-member'>Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree