Histologic Variants of Urothelial Carcinoma

With increasing experience with urothelial carcinomas at the light microscopic level, the spectrum of microscopic forms of urothelial carcinoma has been expanded to include several unusual histologic variants that have been incorporated in the new WHO classification (1). The term “variant” is used to describe a distinctively different histomorphologic phenotype of a certain type of neoplasm (2, 3, 4, 5). By definition, they arise from the surface urothelium. The recognition of histologic variants is important because (a) some types may be associated with a different clinical outcome, and some of them have been incorporated into risk stratification models (6), (b) some may have a different therapeutic approach, or (c) awareness of the unusual pattern may be critical in avoiding diagnostic misinterpretations. We generally recommend following two general rules when dealing with histologic variants. First, the variant histology should be documented in the pathology reports because metastatic tumors usually continue to exhibit the distinctive histologic pattern, and knowledge of the variant histology facilitates association of the metastasis with the primary tumor. Second, because the pattern of the neoplasm deviates from the conventional form, the possibility that this “unusual” morphology represents a metastasis should be considered and ruled out.

DECEPTIVELY BENIGN VARIANTS OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

Some urothelial carcinomas have histologic variants that mimic nonneoplastic conditions such as cystitis cystica, von Brunn’s nests, nephrogenic adenoma, and inverted papilloma (7, 8, 9, 10). Awareness of these variants (nested, urothelial carcinoma with small tubules, microcystic urothelial carcinoma, and inverted papilloma-like growth pattern) is important because limited sampling, particularly in cystoscopic biopsy specimens, could lead to an underdiagnosis of malignancy (7, 8, 9, 10).

Nested Variant of Urothelial Carcinoma

From a pathologist’s perspective, the nested variant should appropriately be recognized as a malignant process, particularly in superficial biopsies.

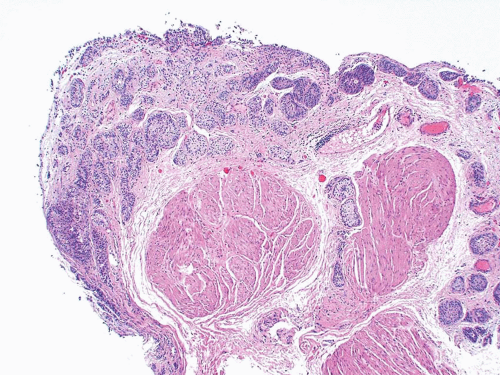

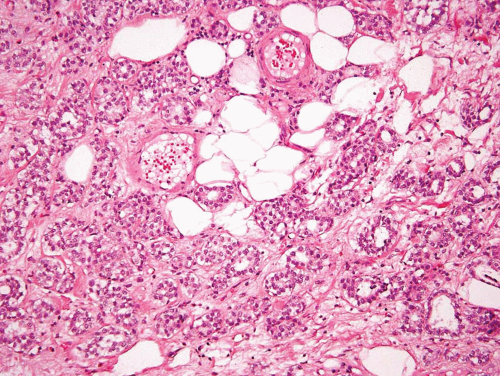

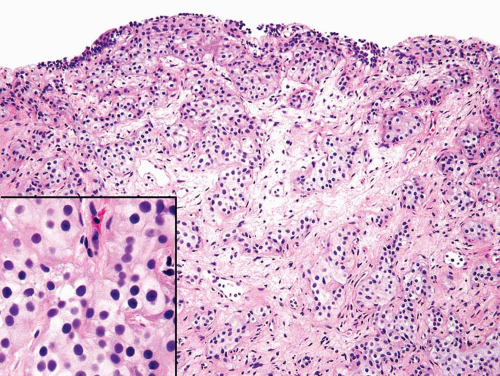

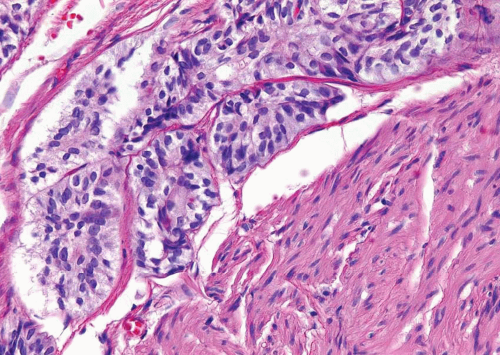

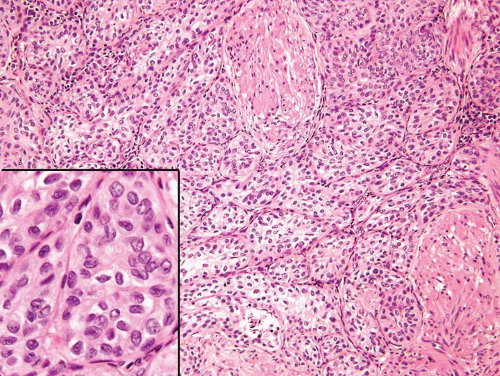

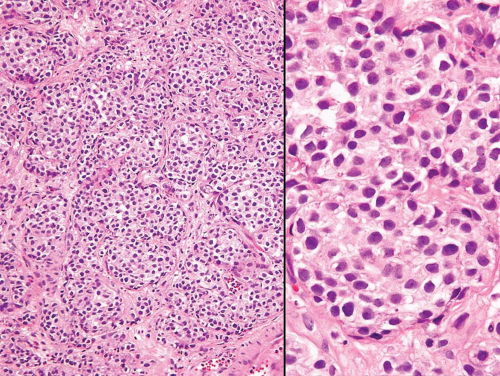

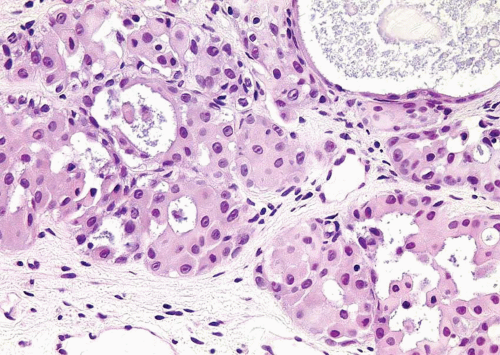

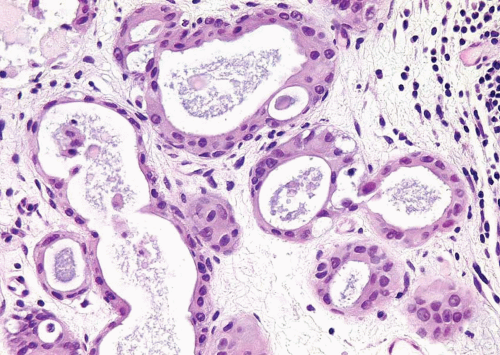

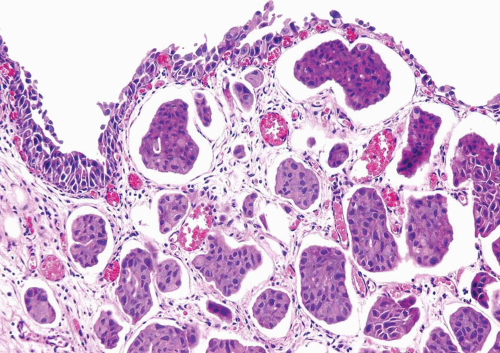

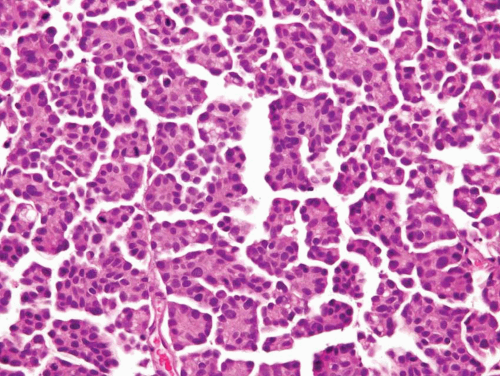

This variant has distinct patterns in the superficial and deep portions. In superficial biopsy samples and transurethral resectates, the superficial component appears as discrete nests, occasionally with tubules (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) (Figs. 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, 6.6, 6.7, 6.8 and 6.9) (efigs 6.1-6.18). The nests are tightly packed, often confluent and haphazardly arranged with little or no intervening stroma. Most nests have a relatively bland cytologic appearance, but at least some have more pleomorphic nuclei and large nucleoli. Overlying papillary carcinoma or recognizable flat in situ disease is most often not present (14). The architectural complexity, confluence, and anastomosis between the nests are features that are particularly helpful in distinguishing carcinoma from von Brunn’s nests or other benign conditions. von Brunn’s nests extend to a uniform level within the lamina propria creating a sharp, linear border at the base that contrasts with the irregular, infiltrative base of nested carcinoma. In the ureter and renal pelvis, von Brunn’s nests tend to be smaller and more crowded than in the bladder, closely mimicking nested carcinoma (Figs. 1.15, 1.16). However, von Brunn’s nests in these sites still have a lobular or linear arrangement with a sharp border at the base. Also, the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma is exceedingly rare in the ureter and renal pelvis.

This variant has distinct patterns in the superficial and deep portions. In superficial biopsy samples and transurethral resectates, the superficial component appears as discrete nests, occasionally with tubules (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) (Figs. 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, 6.6, 6.7, 6.8 and 6.9) (efigs 6.1-6.18). The nests are tightly packed, often confluent and haphazardly arranged with little or no intervening stroma. Most nests have a relatively bland cytologic appearance, but at least some have more pleomorphic nuclei and large nucleoli. Overlying papillary carcinoma or recognizable flat in situ disease is most often not present (14). The architectural complexity, confluence, and anastomosis between the nests are features that are particularly helpful in distinguishing carcinoma from von Brunn’s nests or other benign conditions. von Brunn’s nests extend to a uniform level within the lamina propria creating a sharp, linear border at the base that contrasts with the irregular, infiltrative base of nested carcinoma. In the ureter and renal pelvis, von Brunn’s nests tend to be smaller and more crowded than in the bladder, closely mimicking nested carcinoma (Figs. 1.15, 1.16). However, von Brunn’s nests in these sites still have a lobular or linear arrangement with a sharp border at the base. Also, the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma is exceedingly rare in the ureter and renal pelvis.

FIGURE 6.2 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. The nests are too small and crowded to represent von Brunn’s nests. Inset shows bland cytology. |

FIGURE 6.3 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. The nests are too small and crowded with complex architecture to represent von Brunn’s nests. |

FIGURE 6.4 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma (higher magnification of Figure 6.3). |

FIGURE 6.5 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with focal tubule formation (higher magnification of Figure 6.3). |

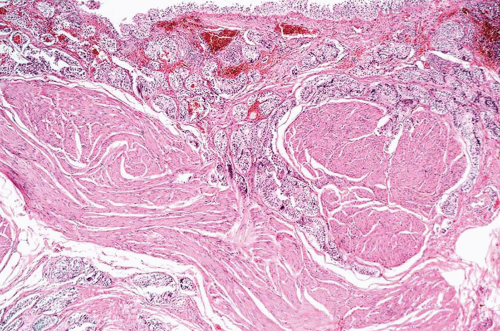

FIGURE 6.7 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Tumor invades muscularis propria (higher magnification of Figure 6.6). |

FIGURE 6.8 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with extension of nests into muscularis propria. Inset shows bland cytology. |

FIGURE 6.9 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with crowded almost back-to-back proliferation of small nests (higher magnification (right)). |

In the deeper portion of the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma, the neoplasm usually shows greater cytologic atypia and an irregular infiltrative pattern. These tumors are frequently muscle invasive and, despite their innocuous histology, are paradoxically associated with aggressive clinical outcome including metastasis and death. Even with therapy, 70% of patients with adequate follow-up died within 4 to 40 months of diagnosis (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). Invasion of the muscularis propria, despite the bland nuclear features, is diagnostic of carcinoma and is the most definitive distinguishing feature. Unfortunately, in some superficial biopsies or those complicated by extensive cautery artifact, it may be difficult to categorize lesions as unequivocally benign or malignant. In such cases, it is important to correlate the microscopic findings with the clinical impression of the urologist, as the presence of a mass lesion would indicate the need for additional sampling to ascertain for the presence of a more aggressive lesion.

Another differential diagnostic consideration is nephrogenic adenoma (metaplasia) with a more solid appearance (8). The problem is compounded when the nephrogenic adenoma has an “infiltrative” growth at the base. The marked variation or occasional large nests, nuclear atypia in deeper aspects, stromal reaction, and muscularis propria invasion argue for a nested carcinoma diagnosis. Nephrogenic adenoma may show other coexisting patterns (tubules, papillary, signet ring, cystic) and often contains stroma that is edematous and inflamed. Several other tumors primarily or secondarily involving the urinary bladder may have a nested pattern including paraganglioma, carcinoid tumor, prostatic adenocarcinoma, melanoma, and alveolar soft part sarcoma (15). In this differential diagnostic context, once the diagnosis of neoplasia is made, the issue is the distinction of urothelial versus nonurothelial nature of the different nested tumors and their distinction from one another by using an appropriately constructed immunohistochemical panel. Immunohistochemical studies indicate that the nested variant shares many characteristics with invasive urothelial carcinoma, including positivity for cytokeratins (CKs), CK7 and CK20, and for p63 and high molecular weight cytokeratin (16, 17, 18, 19). The nested variant shows loss or absence of immunoreactivity for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27 and positivity for tumor suppressor gene p53, which have been associated with poor prognosis in conventional urothelial carcinoma (17). There have been studies supporting MIB-1 as a useful marker in the distinction from benign proliferative lesions, although it must be noted that some cases of nested variant may have low MIB-1 proliferation index and some proliferative lesions may have higher rates (17, 20). This variability and range of immunostaining for MIB-1 has precluded us from using MIB-1 immunohistochemistry as a diagnostic adjunct for such cases.

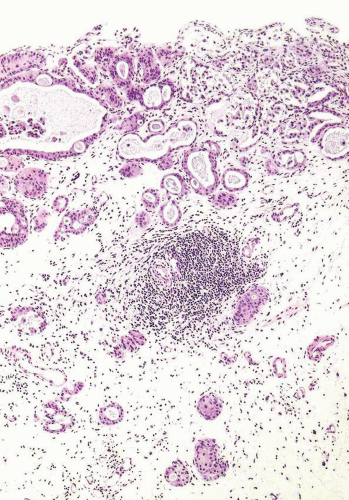

Urothelial Carcinoma with Small Tubules

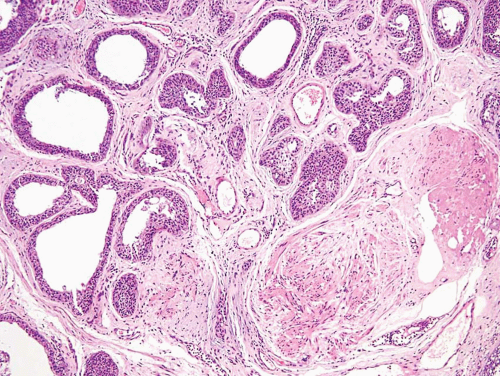

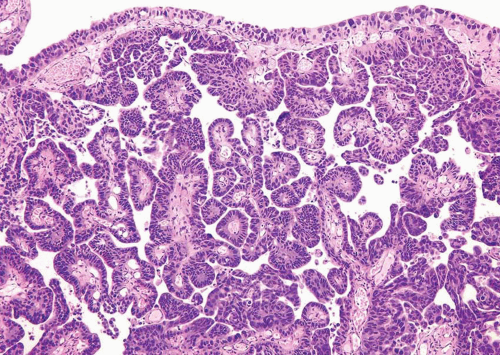

Some urothelial carcinomas may have a prominent component of small-sized to medium-sized, round to elongated tubules that may be misdiagnosed as nephrogenic adenoma (metaplasia) or cystitis glandularis (10, 21) (Figs. 6.10, 6.11, 6.12, 6.13, 6.14 and 6.15). The tubules, however, are lined by urothelial cells in contrast to the cuboidal, columnar, or, occasionally, flattened cells that line the tubules of nephrogenic adenoma. The cytologic features are invariably low grade, but the recognition of carcinoma is based on diffusely infiltrative architecture, considerable variation of tubular shape with haphazard organization, and the frequent presence of muscle invasion. The biologic significance of this pattern is uncertain, but some of these cases occur in conjunction with the nested pattern and may result in an aggressive behavior. The differential diagnosis with an extension of a prostatic carcinoma is often also a consideration but is easily handled by immunohistochemistry (PSA positive in prostate cancer; high molecular weight cytokeratin and p63: positive in more than half of urothelial

carcinomas) (22). Like the nested variant, the chief reason for awareness of this morphologic variant of urothelial carcinoma is not to mistake it in superficial biopsies as a benign glandular proliferative lesion (5, 7, 12, 13, 16, 17, 23).

carcinomas) (22). Like the nested variant, the chief reason for awareness of this morphologic variant of urothelial carcinoma is not to mistake it in superficial biopsies as a benign glandular proliferative lesion (5, 7, 12, 13, 16, 17, 23).

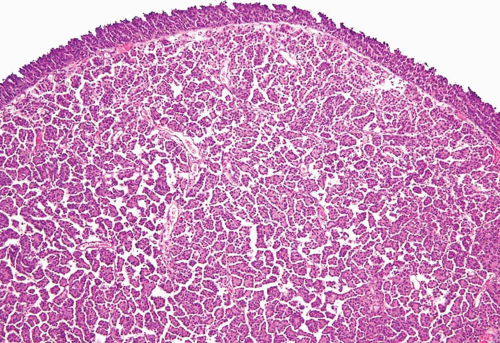

Microcystic Urothelial Carcinoma

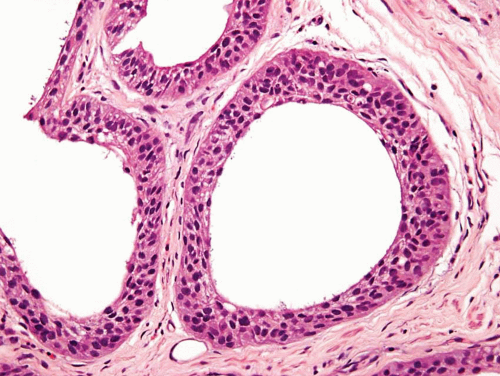

This is yet another deceptively benign form of urothelial carcinoma and is exemplified by the formation of numerous microcysts, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of cystitis cystica upon superficial examination or in limited biopsy specimens (24, 25, 26) (Figs. 6.16, 6.17). The pattern is characterized by prominent widespread cystic change of variable size within nests of urothelial carcinoma or within urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation. The cysts are round to oval, 1 to 2 mm in size, and contain secretions that may be targetoid. The cyst lining is most commonly urothelial and is usually focally glandular; larger cysts may possess a flattened epithelium or a denuded lining. Cytologic blandness is present by definition, and the most critical feature in distinguishing this carcinoma type from benign conditions is the variation, often dramatic, in size and shape of the epithelial formations and the relatively haphazard infiltrative growth into the wall of the urinary bladder. There is no striking biologic significance associated with this pattern, except that it represents a potentially serious diagnostic pitfall, particularly in limited samples (24, 26). Once again, the nested, small tubule, and cystic variants may coexist in the same lesion (10). The chief differential diagnostic considerations are from cystitis cystic et glandularis and von Brunn’s nests, which overall tend to have a very organized appearance and lack the overt size variation that typifies microcystic carcinoma (24, 25, 26, 27).

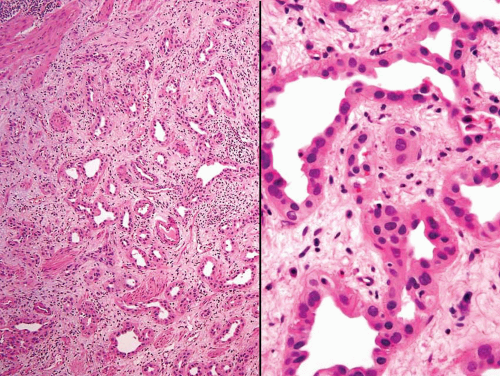

FIGURE 6.12 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with tubule formation. Note irregular proliferation of nests and tubules in inflamed, edematous stroma. |

FIGURE 6.13 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with moderate atypia (higher magnification of Figure 6.12). Although the cytologic features appear “low grade” on low power, this high power illustration shows diagnostic features of malignancy. |

FIGURE 6.14 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with tubule formation (higher magnification of Figure 6.12). |

FIGURE 6.17 Microcystic urothelial carcinoma (higher magnification of Figure 6.16). |

INVERTED PAPILLOMA-LIKE GROWTH PATTERN OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

This form of urothelial carcinoma is associated with two diagnostic concerns: (a) distinction from inverted papilloma (see Chapter 4) and (b) difficulty in assessing invasion (see Chapter 5) (28, 29). Distinction from the inverted papilloma requires attention to the architectural and cytologic features of the lesion. Urothelial carcinomas with inverted growth usually have thicker columns with irregularity in width of the columns or transition of cords and columns into large rounded nests. The characteristic orderly maturation, spindling, and peripheral palisading seen in inverted papilloma are generally absent or inconspicuous in urothelial carcinomas with inverted growth. The amount of stroma between the epithelial columns and cords can be quite variable from area to area. Unequivocal stromal invasion into the lamina propria or muscularis propria rules out the diagnosis of inverted papilloma, as does the presence of appreciable exophytic papillary architecture. Furthermore, cytologic atypia is an important feature for the diagnosis of carcinoma; thus, carcinomas with inverted growth, like their exophytic counterparts, may be classified as low grade or high grade. Inverted urothelial carcinoma may or may not be associated with destructive invasion (see Chapter 5 for criteria for invasion). Although the distinction of inverted papilloma versus carcinoma is usually based on routine light microscopic evaluation, a study has investigated and proposed a role for ancillary techniques, including immunohistochemistry (p53, Ki-67, and CK20 all show statistically significant higher expression in carcinomas as compared to urothelial papillomas) and UroVysion FISH studies (chromosomal abnormalities absent in urothelial papilloma and present in urothelial carcinoma) (30).

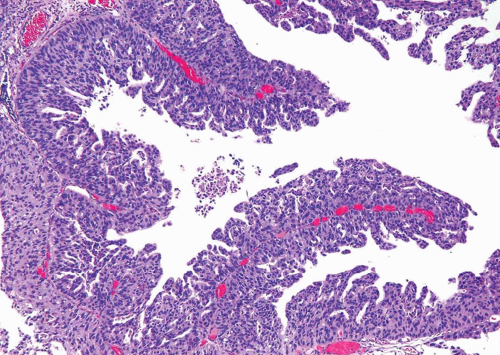

MICROPAPILLARY VARIANT OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

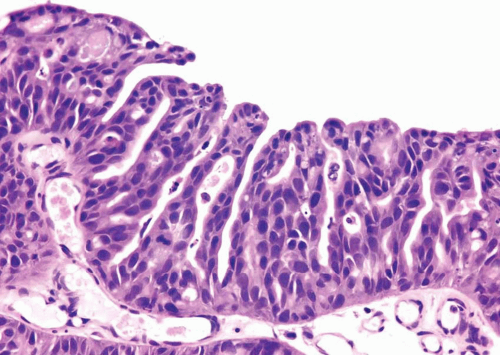

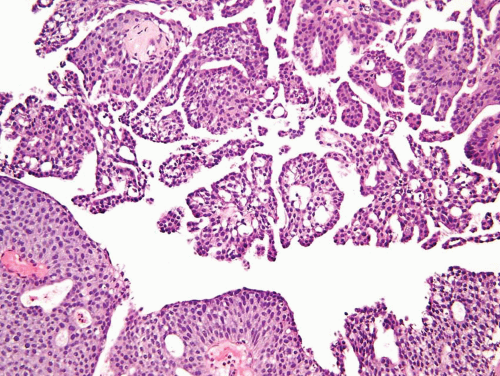

This histologic variant of urothelial carcinoma has a micropapillary architecture that is reminiscent of the papillary configuration seen in ovarian papillary serous tumors (31, 32, 33, 34, 35).

This rare histologic variant comprises 0.6% to 1% of urothelial carcinomas and shows a definite male predominance (male-to-female ratio 5:1) that is higher than in conventional urothelial carcinoma (3:1). More than 95% of these tumors are muscle invasive at the time of presentation. Histologically, the micropapillary component of these tumors may be encountered in (a) the noninvasive component, (b) the invasive component, and (c) metastasis. This pattern may be focal, extensive (greater than 90%), or exclusive. Urothelial carcinoma in situ (urothelial CIS) is demonstrable in greater than 50% of the cases and concurrent glandular differentiation is known to occur. Five histologic features of the micropapillary component are noteworthy. First, micropapillary carcinoma

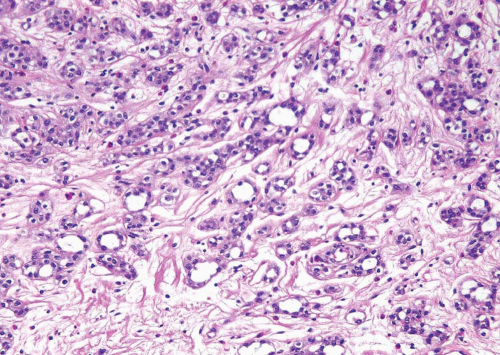

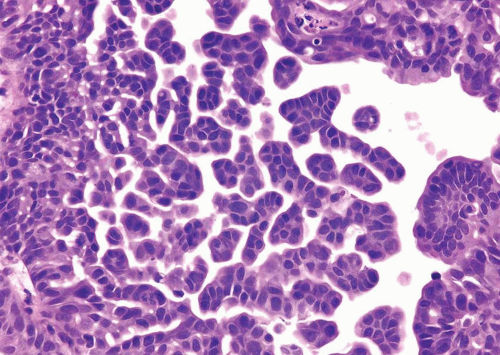

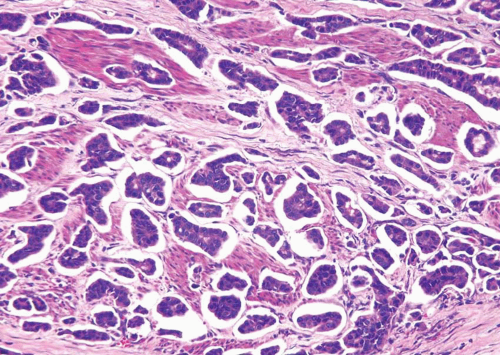

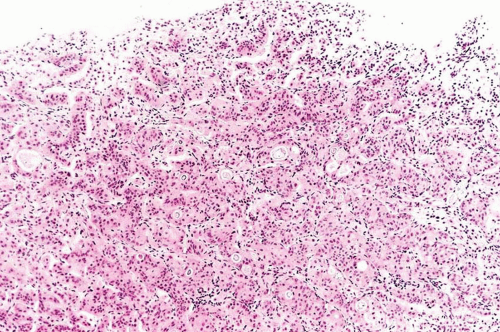

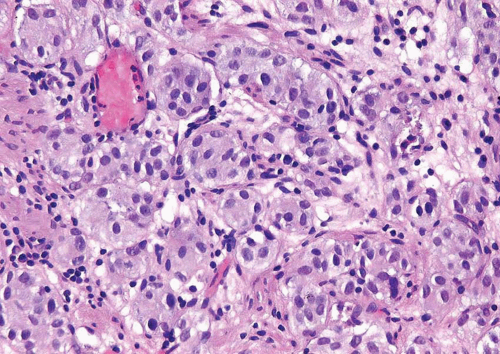

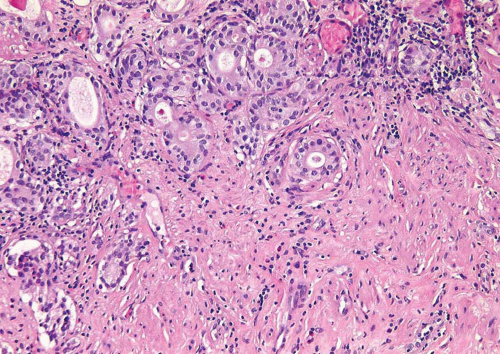

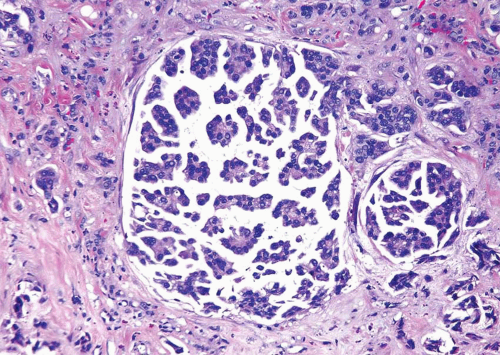

has two distinct patterns: on the surface it forms slender, delicate filiform processes, rarely with a fibrovascular core (Figs. 6.18, 6.19, 6.20 and 6.21) (efigs 6.19-6.22). When cut in cross sections, these papillae appear as glomeruloid bodies. In the invasive component and in all metastatic sites, the tumor cells are arranged in small tight nests or balls (Figs. 6.22, 6.23, 6.24, 6.25, 6.26 and 6.27) (efigs 6.23-6.36). Second, psammoma bodies, a feature of ovarian papillary serous neoplasia, are exquisitely rare in micropapillary carcinoma. Third, the tumor cells in the invasive and metastatic components are aggregated in lacunae, which mimic vascular invasion. This feature is intriguing and extremely characteristic of invasive micropapillary carcinoma. The spaces may be lined focally by flattened spindled cells or may be devoid of any lining. In most instances, there is no host response to the tumor cells that merely seem to reside in hollow spaces at various random intervals within the tumor (34). This pattern of lacunae containing neoplastic cells is also seen in the metastatic sites. Awareness that lacunae of micropapillary urothelial carcinoma may mimic vascular invasion is important so that one does not overdiagnose the presence of vascular invasion. Fourth, micropapillary carcinoma always demonstrates a high nuclear grade (high grade by WHO/ISUP classification), although some areas within a neoplasm may parallel low-grade urothelial carcinoma. Fifth, most reported cases with micropapillary carcinoma show at least focal unequivocal vascular invasion. Like urothelial carcinomas, the tumors are often positive for CK7, CK20, and uroplakin (36). Leu-M1, CEA, and Ca antigen 125 may be focally positive, in keeping with glandular differentiation that may be concurrent.

has two distinct patterns: on the surface it forms slender, delicate filiform processes, rarely with a fibrovascular core (Figs. 6.18, 6.19, 6.20 and 6.21) (efigs 6.19-6.22). When cut in cross sections, these papillae appear as glomeruloid bodies. In the invasive component and in all metastatic sites, the tumor cells are arranged in small tight nests or balls (Figs. 6.22, 6.23, 6.24, 6.25, 6.26 and 6.27) (efigs 6.23-6.36). Second, psammoma bodies, a feature of ovarian papillary serous neoplasia, are exquisitely rare in micropapillary carcinoma. Third, the tumor cells in the invasive and metastatic components are aggregated in lacunae, which mimic vascular invasion. This feature is intriguing and extremely characteristic of invasive micropapillary carcinoma. The spaces may be lined focally by flattened spindled cells or may be devoid of any lining. In most instances, there is no host response to the tumor cells that merely seem to reside in hollow spaces at various random intervals within the tumor (34). This pattern of lacunae containing neoplastic cells is also seen in the metastatic sites. Awareness that lacunae of micropapillary urothelial carcinoma may mimic vascular invasion is important so that one does not overdiagnose the presence of vascular invasion. Fourth, micropapillary carcinoma always demonstrates a high nuclear grade (high grade by WHO/ISUP classification), although some areas within a neoplasm may parallel low-grade urothelial carcinoma. Fifth, most reported cases with micropapillary carcinoma show at least focal unequivocal vascular invasion. Like urothelial carcinomas, the tumors are often positive for CK7, CK20, and uroplakin (36). Leu-M1, CEA, and Ca antigen 125 may be focally positive, in keeping with glandular differentiation that may be concurrent.

FIGURE 6.18 Noninvasive urothelial carcinoma with micropapillary features (top) compared to usual papillary urothelial carcinoma (bottom). |

FIGURE 6.22 Invasive micropapillary carcinoma beneath urothelium, mimicking vascular invasion. There are numerous blood vessels that are uninvolved in between invasive carcinoma. |

FIGURE 6.24 Invasive micropapillary urothelial carcinoma (higher magnification of Figure 6.23). |

FIGURE 6.25 Invasive micropapillary urothelial carcinoma composed of thin cords lacking fibrovascular stalks admixed with conventional papillary urothelial carcinoma. |

FIGURE 6.26 Invasive micropapillary urothelial carcinoma with adjacent usual invasive urothelial carcinoma. |

There are several important reasons for recognizing the micropapillary variant of urothelial carcinoma:

1. These tumors are high grade and high stage and are almost always associated with vascular invasion.

2. Micropapillary carcinoma has a higher DNA index than conventional urothelial carcinoma (limited cases examined) (34), and because metastatic sites of tumors with micropapillary histology are predominantly composed of micropapillary carcinoma, it is likely that this unique configuration of urothelial carcinoma connotes a more aggressive clone of neoplastic cells.

3. The presence of micropapillary histology in metastatic sites forces one to consider the possibility of urothelial carcinoma, especially if the micropapillary configuration is encountered in the peritoneum, abdominal lymph nodes, or mesentery of a male patient with an unknown primary or in a female patient with no apparent abnormality of the gynecologic tract (32, 33, 34, 35). One of the authors (M.B.A.) has seen two cases presenting in supraclavicular lymph nodes of male patients.

4. The high association of micropapillary carcinoma with muscle invasive disease should make the pathologist look diligently for muscle invasion if it is not readily apparent. If the biopsy is superficial and lacks muscularis propria, a second biopsy should be considered. If the biopsy is superficial and lacks muscularis propria, there should be a suggestion for a rebiopsy and reevaluation for staging. There are recent data that suggest that for micropapillary carcinomas presenting as early stage disease, there is limited response to immunotherapy such that one leading group has advocated for early cystectomy for pTa and pT1 tumors with micropapillary histology. Also, patients are likely to progress while on intravesical therapy. The prognosis is uniformly unfavorable; 5-year and 10-year survival in the largest study were 51% and 24%, respectively (39). However, this poor prognosis is similar to that reported in high-grade, high-stage urothelial carcinoma of the usual type as well as pure adenocarcinomas and small cell carcinomas of the urinary bladder (40, 41, 42).

The main differential diagnosis in women is with a metastatic papillary serous carcinoma, especially if the tumor is originally discovered in the peritoneum, abdominal lymph nodes, mesentery, or as a carcinoma of unknown origin. Other sites of carcinomas with micropapillary histology are the lung and breast, and rarely the pancreas and salivary glands. Clinical/radiographic correlation is usually required, but the possibility of a bladder primary may be suggested if there is no obvious primary tumor at another anatomic site. Identification of an admixed urothelial carcinoma of more typical morphology would be helpful (36, 43). In a bladder tumor, pure micropapillary histology may raise concern for a primary adenocarcinoma of the bladder; however, the micropapillary architecture is due to

neoplastic urothelial cells in a micropapillary configuration and not due to true glandular differentiation, as also supported by immunohistochemistry. In primary adenocarcinoma of bladder, there is a greater variability of gland shape and size and range of differentiation in contrast to the typically uniform appearance of micropapillary component of urothelial carcinoma (32, 33, 34, 35, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48). In a study of micropapillary carcinomas from the bladder, ovary, lung, and breast, the following immunohistochemical panel was recommended: CK20 and uroplakin (positive in some bladders), PAX8 or WT-1 (positive in ovary), TTF-1 (positive in lung), and mammaglobin (positive in breast), respectively (49).

neoplastic urothelial cells in a micropapillary configuration and not due to true glandular differentiation, as also supported by immunohistochemistry. In primary adenocarcinoma of bladder, there is a greater variability of gland shape and size and range of differentiation in contrast to the typically uniform appearance of micropapillary component of urothelial carcinoma (32, 33, 34, 35, 39, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48). In a study of micropapillary carcinomas from the bladder, ovary, lung, and breast, the following immunohistochemical panel was recommended: CK20 and uroplakin (positive in some bladders), PAX8 or WT-1 (positive in ovary), TTF-1 (positive in lung), and mammaglobin (positive in breast), respectively (49).

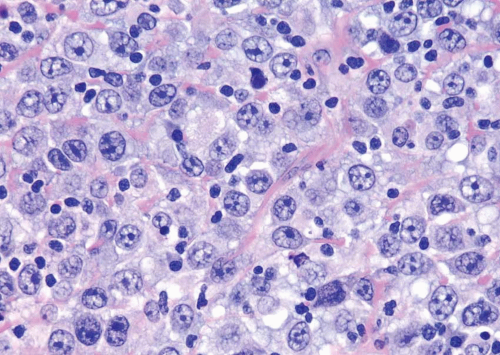

LYMPHOEPITHELIOMA-LIKE CARCINOMA

Tumors with this histology are so termed because of their striking morphologic resemblance to the undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma or lymphoepithelioma (50, 51) (Figs. 6.28, 6.29 and 6.30) (efigs 6.37-6.49). They have also been reported at multiple sites including the prostate, breast, cervix, skin, lung, thymus, stomach, and salivary glands (50). The neoplastic cells are large and arranged in sheets, cords, or trabeculae with syncytia of cells containing vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and numerous mitoses (50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55). The sine qua non for the diagnosis of this histologic pattern of urothelial carcinoma is the presence of a prominent lymphoid infiltrate, although an admixture of other inflammatory cells including plasma cells and eosinophils is not uncommon. The relationship to EBV (by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization) has been well explored with no association being documented (55

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree