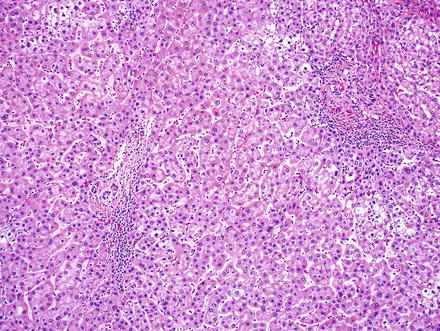

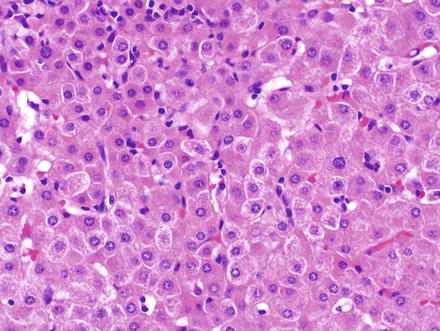

Fig. 6.1

Large cell change. Hepatocytes show nuclear and cytoplasmic enlargement with preserved nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios. Additional cytological changes include multinucleation, hyperchromasia, irregular nuclear contours, nuclear inclusions, and nuclear pleomorphism

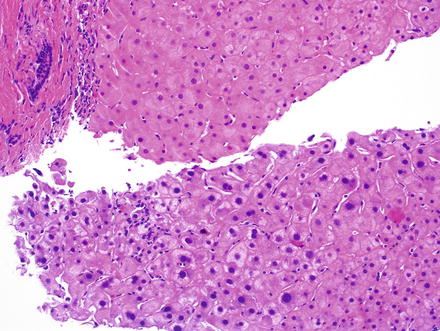

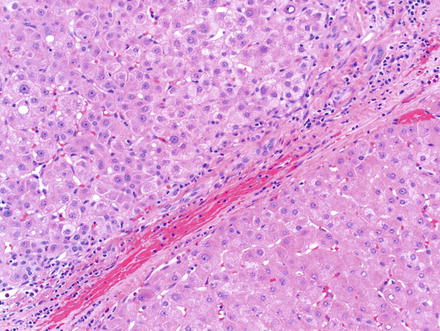

Fig. 6.2

Large cell change in comparison to normal hepatocytes. Note the enlarged and hyperchromatic cells (bottom) with preserved nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios. This focus of large cell change was identified in the adjacent benign liver from a biopsy that showed hepatocellular carcinoma elsewhere

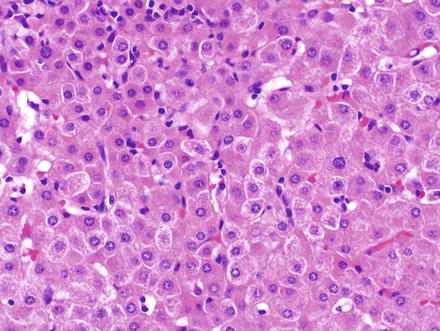

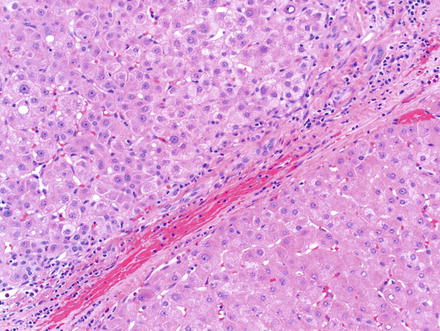

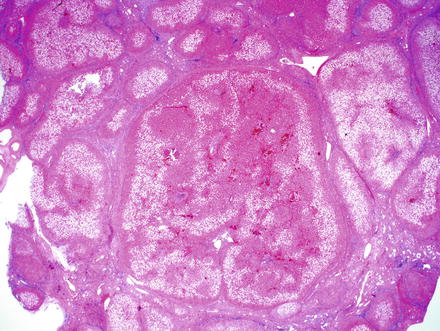

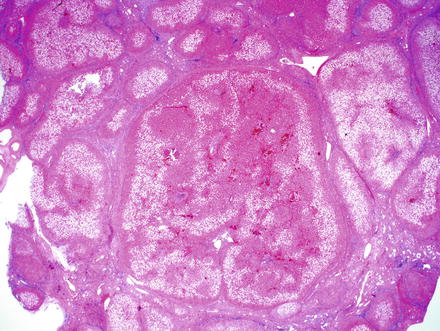

Hepatocytes with small cell change show slight nuclear enlargement and a decrease in cytoplasm, resulting in an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio (Fig. 6.3). This in turn leads to a marked increase in nuclear density, compared to the adjacent liver (Fig. 6.4) [2]. Small cell change also shows nuclear and cytoplasmic basophilia, giving the lesion a “darker” appearance when compared to adjacent normal hepatocytes.

Fig. 6.3

Small cell change. The cells show mild nuclear enlargement, combined with a reduction in cytoplasm, resulting in increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios. The nuclei and cytoplasm show increased basophilia

Fig. 6.4

Small cell change. A focus of small cell change (top-left) adjacent to a nodule of cirrhosis (bottom-right). Note the increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and relative increased basophilia

6.1.4 Immunohistochemical Findings

There are no useful diagnostic immunostains to identify large cell and small cell change, and the diagnosis is made on H&E stain.

6.1.5 Molecular Findings

Large cell change shows variable molecular findings, with evidence that in some cases the changes are reactive and perhaps senescent, while in other cases the changes are likely preneoplastic [12–14]. Small cell change is associated with chromosomal abnormalities, including telomere shorting, tumor suppressor gene inactivation (such as the p21 check point), and a higher proliferation rate [3, 15]. These molecular and chromosomal changes support a model in which small cell change is a direct precursor to hepatocellular carcinoma.

6.1.6 Differential Diagnosis

One mimic of large cell change is regenerative and reactive hepatocytes in the setting of lobular injury and repair. However, the distinction is usually straightforward if attention is paid to the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and nuclear atypia, including multinucleation.

Atrophic hepatocytes can mimic small cell change, showing an increase in nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and mild increased nuclear density. One example is nodular regenerative hyperplasia, where atrophic hepatocytes share some cytological similarities to small cell change. However, small cell change in most cases can be readily distinguished from atrophic hepatocytes by the presence of nuclear atypia and careful examination of the remainder of the biopsy findings. Keep in mind that large cell change and small cell change are most often seen in the setting of advanced liver fibrosis.

The diagnosis of small cell change and large cell change will most often be made in the setting of non-targeted biopsies of livers with chronic disease, such as chronic viral hepatitis. These dysplastic foci are microscopic abnormalities, usually measuring less than 1 mm in diameter. Larger lesions, or lesions seen by imaging, will fall into the categories of macroregenerative nodules, dysplastic nodules, or hepatocellular carcinoma.

6.2 Macroregenerative and Dysplastic Nodules

6.2.1 Definition/Nomenclature

Dysplastic nodules are defined grossly as nodular lesions that are distinctly different from adjacent cirrhotic nodules with respect to size, color, texture, and/or degree of bulging from the cut surface. Although the gross characteristic help in directing sampling of resected specimens, the diagnosis of these lesions requires histologic examination.

There is a continuous morphological progression from macroregenerative nodules to dysplastic nodules with low-grade dysplasia and the diagnostic distinction between these entities is challenging. Macroregenerative nodules were originally described as cirrhotic nodules distinctly larger than the surrounding nodules of cirrhosis [4]. Histologically these nodules contain portal tracts and the hepatocytes are identical to those of adjacent nodules [1]. Macroregenerative nodules are benign and not directly pre-neoplastic. Because of the difficulty in clearly defining a macroregenerative nodule versus a dysplastic nodule with low-grade dysplasia, some authors have recommended including macroregenerative nodules in the low-grade dysplastic nodule category [1]. However, the basic concept of a large, benign regenerative nodule without any atypia is clinically useful and still retains significant practical value. Dysplastic nodules are further divided into low- and high-grade dysplastic nodules based on histologic features.

6.2.2 Clinical Findings

As with large cell change and small cell change, macroregenerative and dysplastic nodules arise in the setting of chronic liver disease as a result of chronic inflammation, DNA damage and repair, and the subsequent accumulation of mutations. Dysplastic nodules are seen only in the setting of cirrhosis. Macroregenerative nodules are most commonly found in cirrhotic livers, but can rarely be seen following widespread parenchymal extinction from fulminant hepatitis.

Macroregenerative nodules and dysplastic nodules may be identified by imaging studies while screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. However, they typically do not show the high levels of hypervascular intensity on arterial phase of contrast imaging that is typical of hepatocellular carcinoma. Instead they are hypo- or isovascular in comparison to the background liver. In needle biopsy specimens, it can be helpful to know the imaging characteristics of the nodule. Subtle areas of hypervascularity on imaging may indicate progression of a dysplastic nodule to hepatocellular carcinoma.

Dysplastic nodules are associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma and their identification may increase screening frequency. One study carefully followed dysplastic nodules for a median of about two years and found that 46 % of dysplastic nodules disappeared, but 12 % progressed to hepatocellular carcinoma. Of note, another 24 % of individuals developed hepatocellular carcinoma, though not in the dysplastic nodule that was being followed [16].

Low-grade dysplastic nodules are typically followed clinically and radiographically and no immediate treatment is indicated. High-grade dysplastic nodules have a much greater risk for progression to hepatocellular carcinoma. The optimal treatment strategy for high-grade dysplastic nodules is the topic of active investigation, with the need to balance both the risk of overtreatment of lesions that will not progress and under treatment of lesions that are likely to progress. Some centers in the USA treat high-grade dysplastic nodules in the same way they treat well-differentiated HCC and may chemoembolize, radioablate, or transplant these lesions [17, 18].

6.2.3 Gross Findings

Macroregenerative nodules and dysplastic nodules are nodular lesions that differ in size, color, and consistency from the adjacent nodules of cirrhosis (Fig. 6.5). They may be single or multiple and typically measure greater than 1.5 cm. The lesions may bulge from the cut surface or may show a rust (iron), green (bile), or yellow (fat) cut surface. A “nodule within nodule” appearance may be seen grossly. In the setting of genetic hemochromatosis, the nodules can show less or absent iron, compared to the background liver, a finding called “iron free foci.”

Fig. 6.5

Dysplastic nodule. Grossly the lesion is distinctly different from the surrounding cirrhotic nodules, with respect to both size and color. This lesion was 1.1 cm in diameter

6.2.4 Microscopic Findings

Macroregenerative nodules have portal tracts and these portal tracts can show mild chronic inflammation and mild ductular reactions. The hepatocytes show no atypia and are identical cytologically to the hepatocytes in the rest of the liver. There may be fatty change when the rest of the liver also has steatosis.

Dysplastic nodules are identifiable at low power as nodules that are larger and distinctive compared to the other nodules of cirrhosis (Fig. 6.6). Low-grade dysplastic nodules typically show numerous portal tracts, some of which may be fibrotic and expanded. Unpaired arteries in the lobules are typically few or absent. The hepatic plate architecture is preserved at two cells thick. The cell density is mildly increased, but not to the same degree that is seen in hepatocellular carcinomas. Nuclei show mild atypia with nuclear enlargement and irregularities. Mitoses are infrequent. Pseudoglands are typically not seen, unless the liver as a whole is cholestatic. In addition, dysplastic nodules may have steatosis, but the fatty change is similar to that in the adjacent cirrhotic nodules. They do not have “nodule-in-nodule” morphology. Large cell change may be seen within or adjacent to low-grade dysplastic nodules.

Fig. 6.6

Dysplastic nodule. The liver was cirrhotic due to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and this lesion was distinct at the time of gross inspection. The presence of portal tracts with preserved hepatic plate architecture and only mild nuclear atypia are most consistent with a low-grade dysplastic nodule

High-grade dysplastic nodules show obvious cytological and architectural atypia but the changes fall short of malignancy (Fig. 6.7). In high-grade dysplastic nodules, the cell density is 1.5–2 times normal and there may be mild thickening of the hepatic plates, up to three cells thick. Portal tracks are commonly present within high-grade dysplastic nodules, but their numbers are typically fewer than in low-grade dysplastic nodules and macroregenerative nodules. Unpaired arteries can also be seen and the hepatocyte nuclei are atypical with hyperchromasia, and irregular contours. Small cell change may be present. A “nodule-in-nodule” appearance may be present, along with increased steatosis (when compared to adjacent cirrhotic nodules). Pseudoglands (Fig. 6.8) and an increased frequency of sinusoidal endothelization, demonstrated by diffuse CD34 staining, are often encountered. Reticulin stains often show subtle abnormalities, but do not show sufficient loss to diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma.