(Mariani et al., 1989; Ritchie et al., 1986)

■ Transient hematuria

■ Exercise

■ Trauma

■ Menstruation

■ Sexual intercourse

■ Viral illness

■ Anticoagulant toxicity

■ Persistent hematuria

■ Urologic causes (more common)

• Cystitis/urethritis

• Trauma (including Foley catheter)

• Kidney stones (can be detected on renal ultrasound, CT scan without contrast) (Teichman, 2004)

• Benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), prostatitis, or prostate cancer

• Bladder, ureteral, or renal cancer (most common in male smokers) (Mulholland & Stefanelli, 1990)

■ Nephrologic causes

• Glomerulonephritis (GN)—differential diagnosis of isolated glomerular hematuria is IgA nephropathy (Tanaka et al., 1996), Alport’s disease, thin basement membrane disease

• Sickle cell disease/trait (sickling in kidney medulla leading to infarction)

• Vascular (arteriovenous malformation, renal infarct)

• Cystic disease (e.g., polycystic kidney disease)

• Medullary sponge kidney

• Hypercalciuria/hyperuricosuria (±stones)

Isolated Hematuria | |

4.1 |

|

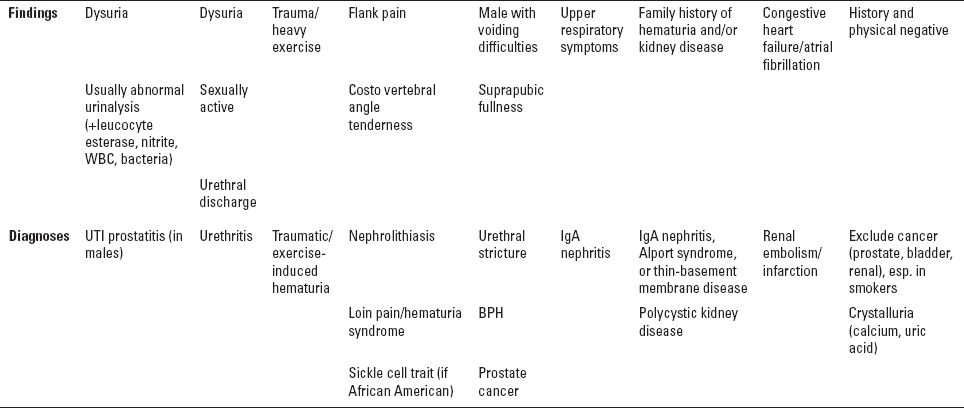

Most Likely Diagnoses Based on History, Physical Examination, and Laboratory Findings

UTI, urinary tract infection.

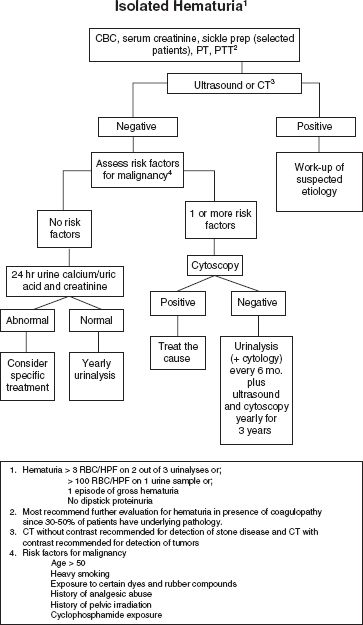

EVALUATION OF ISOLATED HEMATURIA

The steps in evaluation of isolated hematuria are presented in Figure 4.1.

FIGURE 4.1 Evaluation of isolated hematuria.

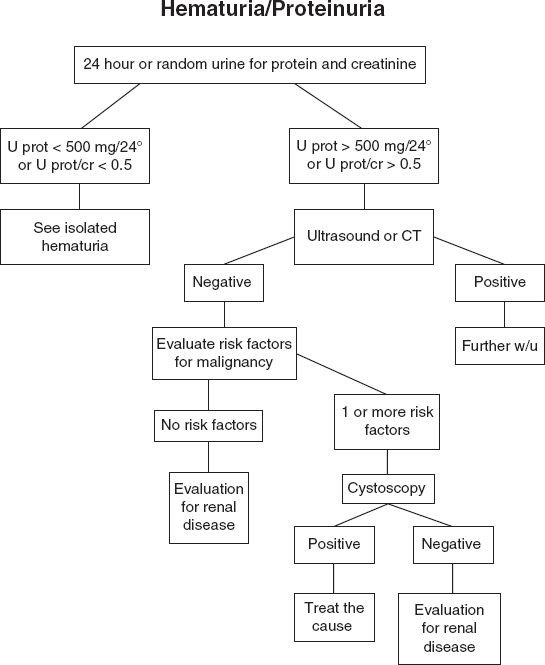

EVALUATION OF HEMATURIA/PROTEINURIA (SEE FIG. 4.2)

■ Suspect GN or renal vasculitis (see Chapter 10)

FIGURE 4.2 Evaluation of hematuria/proteinuria.

A 60-year-old white male with a history of a seizure disorder for the past 40 years presents for evaluation of new-onset asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. He denies trauma, pain/burning with urination, or recent exertion/exercise. He has no abdominal pain. His urinary stream is strong and there is no nocturia. His prostate-specific antigen (PSA) 6 months ago was normal. He denies sore throat, viral syndrome, or recent bacterial infection. He has no history of kidney disease. His only medication is phenytoin. His physical examination is significant only for an enlarged prostate on rectal examination.

Sodium, 138 mmol/L

Potassium, 4.2 mmol/L

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree