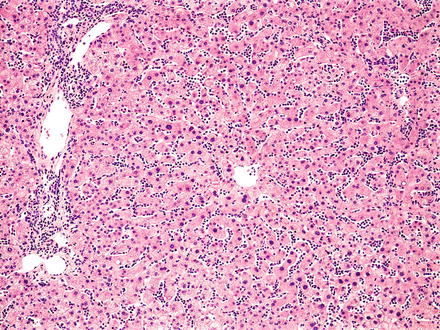

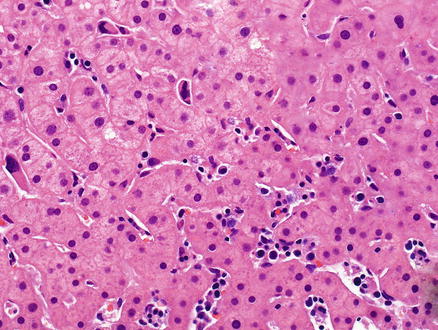

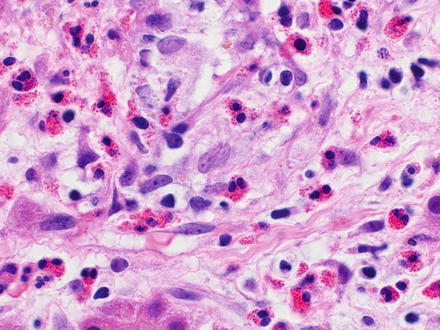

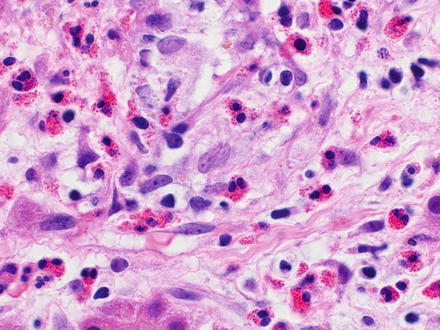

Fig. 12.1

The hemophagocytic syndrome. The sinusoids show prominent benign histiocytes containing phagocytized erythrocytes

12.2 B-Cell Lymphomas

12.2.1 Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma and Mantle Cell Lymphoma

12.2.1.1 Definition

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphomas (CLL/SLL) are small B-cell lymphomas with a characteristic immunophenotypic coexpression of CD5 and CD23 and admixed prolymphocytes and paraimmunoblasts, which can form proliferation centers [17].

12.2.1.2 Clinical Findings

The mean age at diagnosis is 65 years and the male-to-female ratio is 1.5–2:1 [17]. At presentation, patients have a range of clinical findings, from being asymptomatic to presenting with fatigue, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, infections, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and/or extranodal infiltrates [18, 19]. CLL/SLL is generally regarded as an indolent but incurable neoplasm [10]. Richter’s syndrome (also known as Richter’s transformation), the development of a more aggressive large-cell lymphoma, is observed in up to 10 % of patients and portends a poor prognosis. Patients with Richter’s syndrome present with sudden clinical deterioration, fever, weight loss, and enlargement of the sites involved [20]. The lymphomas developing in Richter’s syndrome are typically diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, but can also be classical Hodgkin lymphoma [17].

12.2.1.3 Microscopic Findings

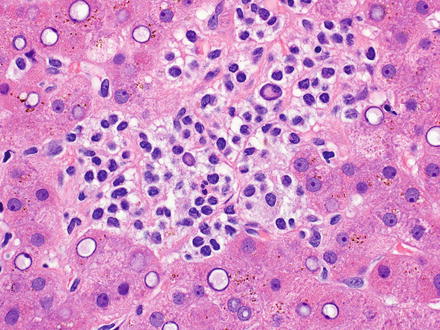

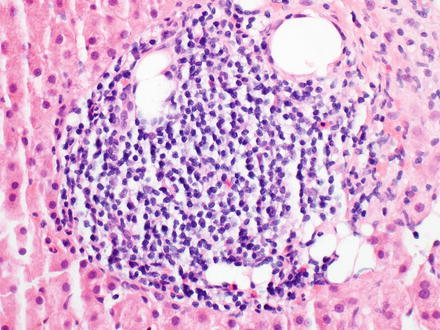

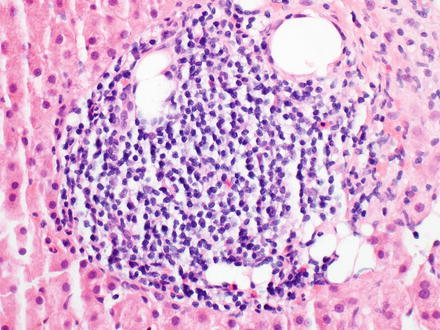

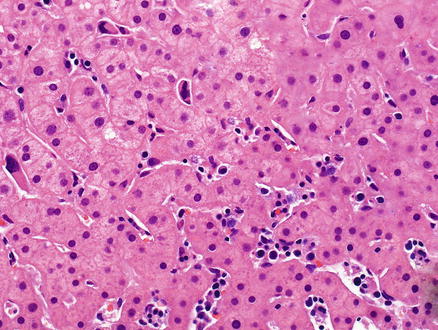

CLL/SLL effaces the normal architecture of the liver with a monomorphic population of small lymphocytes. In many cases, the infiltration predominately involves the portal tracts, leading to expanded, nodular aggregates of lymphocytes within the portal tracts (Fig. 12.2). Crush artifact is common, even on needle biopsy. In cases with marked liver involvement, the neoplasm can be seen within the lobules too. The small lymphocytes have a round nucleus with coarsely clumped chromatin and scant cytoplasm. In the portal tracts, there may be a pseudofollicular growth pattern with regularly distributed, ill-defined pale areas that correspond to proliferation centers, a unique finding to CLL/SLL. Identified within the proliferation centers is a mixture of prolymphocytes and paraimmunoblasts. Prolymphocytes are small to medium-sized cells with clumped chromatin and small nucleoli. Paraimmunoblasts are larger cells with round to oval nuclei, dispersed chromatin, a central eosinophilic nucleolus, and basophilic cytoplasm [10, 17].

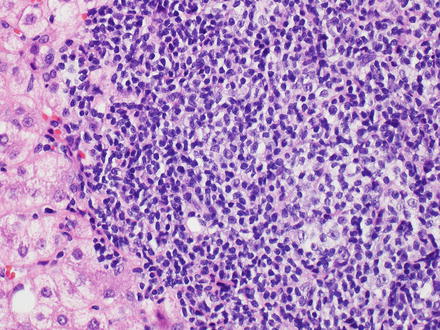

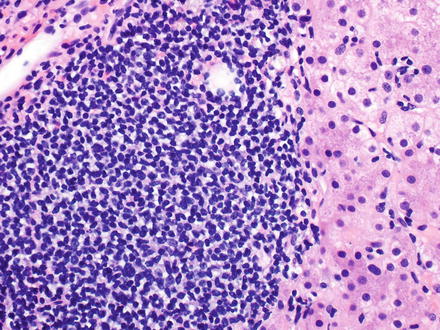

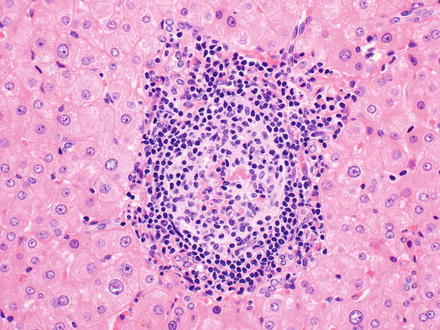

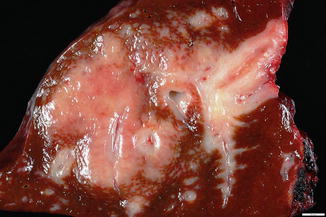

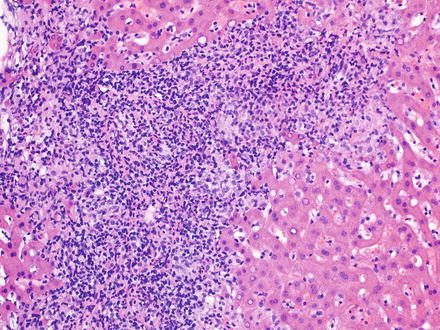

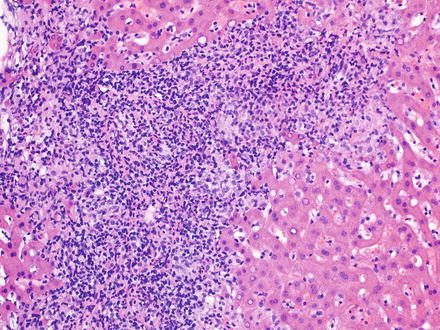

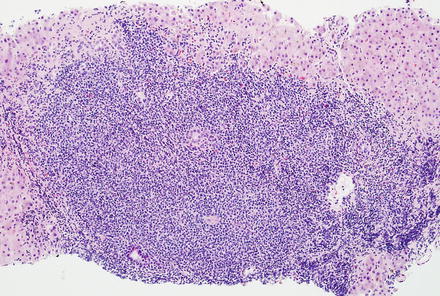

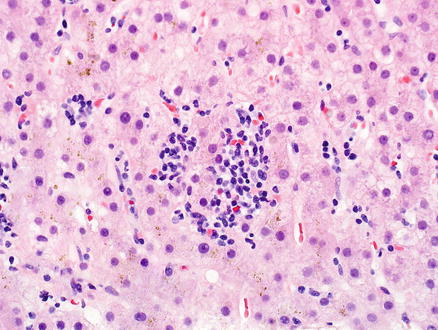

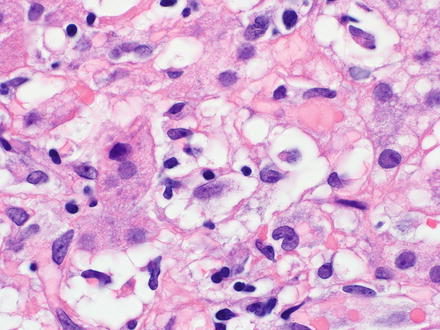

Fig. 12.2

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. The portal tracts are markedly expanded by small monotonous lymphocytes. A proliferation center is also seen (center)

12.2.1.4 Immunohistochemical Features

12.2.1.5 Flow Cytometry

12.2.1.6 Prognostic Factors

Unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain genes (germline variable region) and expression of ZAP-70, CD38, CD49d, and/or NOTCH1 are all associated with an adverse prognosis [21–23]. Deletions of 11q22–23, 17p, and 6q are associated with a worse outcome, while an isolated deletion of 13q14.3 is associated with a more favorable outcome [24, 25].

12.2.1.7 Differential Diagnosis

12.2.1.8 Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma is composed of monomorphic small to medium-sized B-cell lymphocytes with irregular nuclear contours that resemble centrocytes (Fig. 12.3) [26–32]. Prolymphocytes, paraimmunoblasts, and proliferation centers are absent. Hyalinized small vessels and scattered single epithelioid histiocytes are commonly seen [17]. The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes are positive for pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5) with coexpression of CD5 and cyclin D1 and aberrant expression of CD43 [33–35]. They are negative for CD10 and CD23 [17, 27, 36–43]. Flow cytometry demonstrates neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes that are CD19 positive with bright monotypic surface immunoglobulin light chain expression, bright CD20 expression, and coexpression of CD5 and FMC7 [27, 31, 32]. They also express CD22, but not CD10 or CD23. A t(11;14)(q13;q32) chromosomal abnormality is typically present and results in a fusion between the cyclin D1 (CCND1) and immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) genes [27, 39, 44–50].

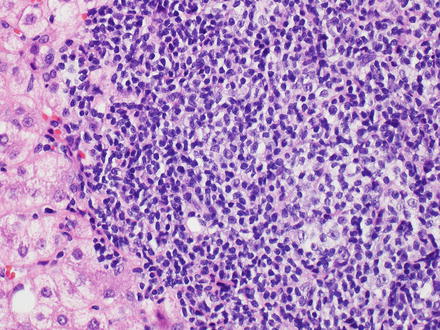

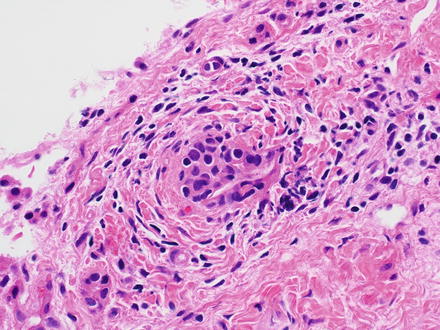

Fig. 12.3

Mantle cell lymphoma. The portal tracts have a dense infiltrate of monomorphic small to medium-sized B-cells with irregular nuclear contours

12.2.2 Marginal Zone Lymphoma

12.2.2.1 Definition

Marginal zone lymphomas are morphologically heterogeneous small B-cell lymphomas composed of marginal zone lymphocytes resembling monocytoid B-cells, small lymphocytes, and scattered immunoblasts and centroblast-like cells that surround lymphoid follicles in a marginal zone distribution pattern, and replace lymphoid follicles [17, 51]. Marginal zone lymphoma encompasses various types: splenic, nodal, and extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). The diagnosis of marginal zone lymphoma requires exclusion of other low-grade, small B-cell lymphomas and clinical correlation to properly classify and to assess the extent of disease.

12.2.2.2 Clinical Findings

The epidemiology and clinical features are dependent upon the type of marginal zone lymphoma. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma occurs in adults over the age of 50 with an equal sex distribution [52]. Patients present with splenomegaly, which can lead to autoimmune thrombocytopenia or anemia. The bone marrow is regularly involved and the liver may be involved, but peripheral lymphadenopathy and other extranodal infiltration is extremely uncommon. Approximately one-third of patients can have a monoclonal serum protein, usually IgM [52, 53].

MALT lymphomas tend to occur in adults, with a median age of 61 and a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.2 [54]. The gastrointestinal tract is the most common site of involvement [55]. There is typically a history of a chronic inflammatory disorder that results in accumulation of extranodal lymphoid tissue. The chronic inflammation may be due to infection, autoimmunity, or other unknown stimulus. Known factors include Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric MALT lymphoma or Sjögren syndrome in salivary gland MALT lymphoma [17, 56–58]. Patients typically present with stage I or II disease [59–61]. Risk factors for primary liver MALT lymphomas include Sjögren syndrome, primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, and possibly chronic hepatitis C and chronic hepatitis B [2, 62].

12.2.2.3 Microscopic Findings

Marginal zone lymphomas show a portal tract centered lymphoid infiltrate composed of small lymphocytes (Fig. 12.4). The lymphoid infiltrate may form lymphoid follicles with the neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes identified external to a preserved mantle zone, in a marginal zone distribution pattern. The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes may extend beyond the marginal zone into the surrounding tissue to form confluent areas. They may also efface the mantle zone and eventually overrun/replace the lymphoid follicles, a pattern called follicular colonization [10, 53, 63–65]. Characteristic marginal zone B-cells are small to medium-sized with slightly irregular nuclear contours, dispersed chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and relatively abundant, pale cytoplasm. Accumulation of additional cytoplasm gives a monocytoid appearance to some of the neoplastic lymphocytes. Additionally, the neoplastic lymphocytes may resemble small lymphocytes and/or have plasmacytic differentiation. Scattered large cells, resembling centroblasts or immunoblasts, are also present, but only make up a minority of the cell population [17, 51, 53, 66–69]. Lymphoepithelial lesions involving the bile ducts can also be seen [10]. Lymphoepithelial lesions are aggregates of three or more marginal zone cells with distortion or destruction of the epithelium, often together with eosinophilic degeneration of the epithelial cells [17].

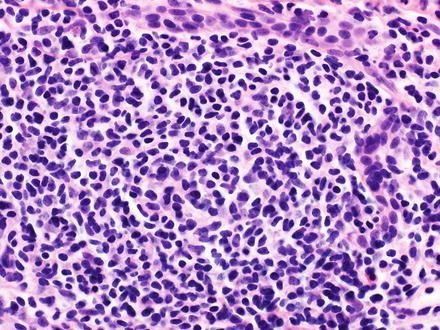

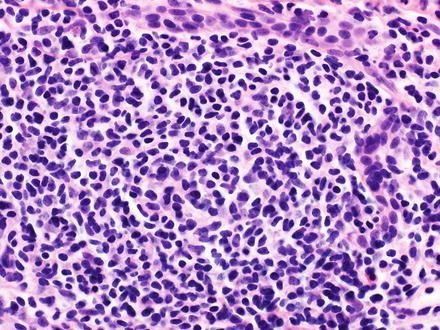

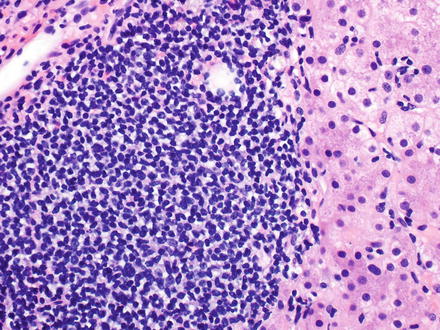

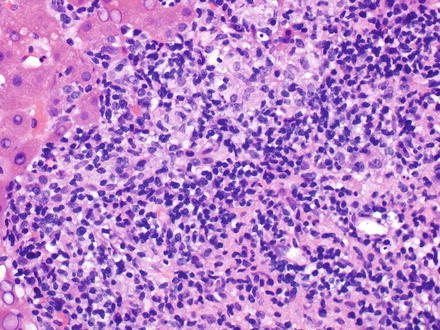

Fig. 12.4

Marginal zone lymphoma (MALT lymphoma). A dense infiltrate of small to medium-sized lymphocytes is seen

12.2.2.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes are positive for pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5), are immunoglobulin light chain restricted, and express immunoglobulin heavy chain, typically IgM. They also typically express the marginal zone cell-associated antigens CD21 and CD35. They may or may not express CD43 and/or CD11c (weak if positive). CD103 is usually, but not always, negative. Most importantly, there is classically a lack of expression of the characteristic markers for other small B-cell lymphomas like CD5, CD10, CD23, cyclin D1, and Annexin-1 [17, 64, 66–68, 70–73].

12.2.2.5 Flow Cytometry

The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes are CD19 positive with bright monotypic surface immunoglobulin light chain expression and bright CD20 expression. They also express CD22 and may or may not express CD11c (weak if positive). CD103 is usually, but not always, negative. Classically, they lack the expression of characteristic markers found on other small B-cell lymphomas like CD5, CD10, and CD23 [17, 64, 71, 73].

12.2.2.6 Molecular Features

In splenic marginal zone lymphomas, allelic loss of chromosome 7q31–32 is observed in up to 40 % of cases [74]. In MALT lymphoma, multiple chromosomal abnormalities are observed, whose frequencies vary with site of primary disease, and include t(11;18)(q21;q21) resulting in a fusion between the BIRC3 and MALT1 genes, t(14;18)(q32;q21) resulting in a fusion between the IGH and MALT1 genes, t(1;14)(p22;q32) resulting in a fusion between the BCL–10 and IGH genes, and t(3;14)(p14.1;q32) resulting in a fusion between the FOXP3 and IGH genes [75–81]. Trisomies 3 and 18 are also relatively frequent in MALT lymphoma [17].

12.2.2.7 Prognostic Factors

Adverse clinical prognostic factors for splenic marginal zone lymphoma include a large tumor mass and poor general health status [82]. Other factors associated with a poor prognosis for splenic marginal zone lymphoma include mutated TP53, 7q deletion, unmutate IGH genes (germline variable region genes), and NOTCH2 mutations [70, 82–86]. Overall, the prognosis of MALT lymphoma in the liver is variable, with some studies reporting a good response to a combination of early surgery and postoperative chemotherapy [10, 87].

12.2.2.8 Differential Diagnosis

12.2.3 Hairy Cell Leukemia

12.2.3.2 Clinical Findings

The median age of onset in hairy cell leukemia is 50 years with a male predominance [88]. Patients typically present with weakness, fatigue, left upper quadrant pain due to splenomegaly, fever, bleeding, and pancytopenia. In particular, monocytopenia is a characteristic finding. Patients can also have hepatomegaly and recurrent opportunistic infections [89].

12.2.3.3 Microscopic Findings

In the liver, neoplastic B-cells may involve both the portal tracts and the sinusoids (Fig. 12.5) [17, 90, 91]. The neoplastic B-cells in hairy cell leukemia are small to medium-sized with oval or indented nuclei, homogeneous and spongy chromatin, absent or inconspicuous nucleoli, abundant pale blue cytoplasm, and prominent cell borders imparting a “fried-egg” appearance (Fig. 12.6). Mitotic figures are uncommon. The circumferential “hairy” projections are only appreciated on peripheral blood and bone marrow aspirate smears. Red blood cell lakes can be identified within the sinusoids and are characterized by collections of pooled erythrocytes surrounded by elongated neoplastic cells [92–94].

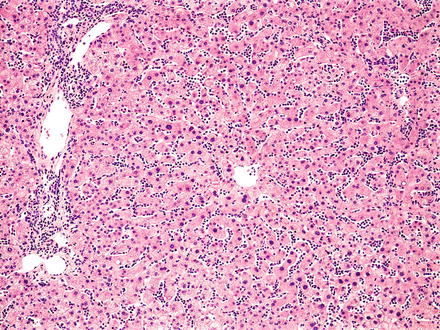

Fig. 12.5

Hairy cell leukemia. A dense infiltrate of lymphocytes fills the sinusoids

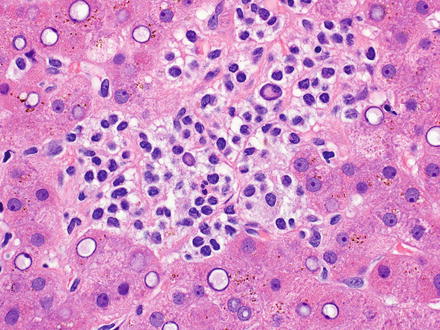

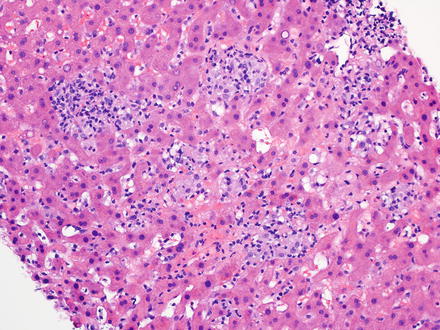

Fig. 12.6

Hairy cell leukemia. The tumor cells have abundant pale cytoplasm and prominent cell borders

12.2.3.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes are positive for pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5) with coexpression of CD11c, CD25, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, Annexin-1, DBA.44, and cyclin D1 (usually weak) [94–102]. Classic cases of hairy cell leukemia will lack expression of both CD5 and CD10 [103, 104].

12.2.3.5 Flow Cytometry

The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes are CD19 positive with bright monotypic surface immunoglobulin light chain expression, bright coexpression of CD20, CD22, and CD11c, and expression of CD103 [105]. Again, classic cases will lack expression of both CD5 and CD10.

12.2.3.6 Molecular Features

12.2.3.7 Prognostic Features

Patients have a good prognosis, as hairy cell leukemia is typically sensitive to purine analogues, with or without rituximab. New therapeutic agents, which target molecular pathways (i.e., inhibitors of BRAF and the MAPK pathway), are still under investigation and show potential to be beneficial in patients with relapsed disease [110, 111].

12.2.3.8 Differential Diagnosis

Because hairy cell leukemia has predominantly a sinusoidal pattern in the liver, the differential diagnosis includes hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (see Sect. 12.3.2). In some cases, a non-neoplastic viral, autoimmune, or drug hepatitis can also be in the differential.

12.2.4 Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma

12.2.4.1 Definition

12.2.4.2 Clinical Findings

The median age at time of diagnosis is 60 and males are affected more often than females [113, 114]. Anemia leads to weakness and fatigue in these patients. Although not required for diagnosis it is often associated with a paraprotein, usually of the IgM type. The paraprotein can lead to hyperviscosity, autoimmune phenomena, cryoglobulinemia, neuropathies, diarrhea, and/or coagulopathies [115–117]. Some cases are associated with hepatitis C virus infection [118]. Patients typically have an indolent clinical course [113, 114].

12.2.4.3 Microscopic Findings

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma effaces the normal architecture of the liver with a monomorphic proliferation of small, round lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm admixed with plasmacytoid lymphocytes and plasma cells, which all together have a nodular to diffuse growth pattern (Fig. 12.7). Dutcher bodies and Russell bodies (intranuclear pseudoinclusions and cytoplasmic inclusions, respectively, containing PAS-positive immunoglobulins) can be identified within the plasmacytoid lymphocytes and plasma cells. An increase in mast cells is typically present. Few transformed cells/immunoblasts are identified. Proliferation centers and paler-appearing marginal zone type differentiation are absent. Some cases can show clusters of epithelioid histiocytes, amyloid or other immunoglobulin deposition, and/or crystal storing histiocytes [17, 119–122].

Fig. 12.7

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma. This patient had a known history of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and liver biopsy showed a small, nodular infiltrate in the portal tracts and to a lesser degree the sinusoids

12.2.4.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic B-cells lymphocyte are positive for pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5), CD38 (frequently), and negative for CD5 (occasionally positive), CD10, CD23, and CD103. The neoplastic lymphocytes express surface immunoglobulin, while the plasmacytoid cells express cytoplasmic immunoglobulin, usually IgM. The plasma cells are positive for CD138 [17].

12.2.4.5 Flow Cytometry

The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes are CD19 positive with bright monotypic surface immunoglobulin light chain expression, bright CD20 expression, and CD22 expression. They frequently coexpress CD38 and do not express CD5 (occasionally positive), CD10, CD23, or CD103 [17].

12.2.4.6 Molecular Features

A highly recurrent somatic mutation of MYD88 L265P, on chromosome 3p22.2, which activates NF kappa B is seen in the majority of patients with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma [123].

12.2.4.7 Prognostic Factors

Clinical prognostic factors associated with a worse prognosis include advanced age, low hemoglobin and platelet count, and high β-2 microglobulin levels [113, 114, 124]. Cases with increased transformed cells/immunoblasts and/or deletions of 6q are also associated with an adverse prognosis [112, 125, 126].

12.2.5 Follicular Lymphoma

12.2.5.1 Definition

12.2.5.2 Clinical Findings

The median age at diagnosis is in the sixth decade and there is a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.7. At the time of diagnosis, patients with follicular lymphoma typically have widespread disease manifested by peripheral and central lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly; otherwise, they are typically asymptomatic [17]. Twenty-five to 35 % of patients will transform/progress to a high-grade lymphoma, usually diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which carries a poor prognosis [10, 128–132].

12.2.5.3 Microscopic Findings

Follicular lymphoma effaces the normal architecture of the liver with a lymphoid infiltrate that typically has a follicular growth pattern (at least focally). The neoplastic follicles are closely packed, have attenuated to absent mantle zones, lack polarization of centrocytes and centroblasts into light and dark zones, and typically lack tingible-body macrophages (Fig. 12.8). Follicles may be large, irregular, and serpiginous. If questioning whether areas with a more confluent growth pattern represent large follicles or diffuse areas, positive immunohistochemical staining for follicular dendritic cells (CD21 or CD23) support the former [17]. The growth pattern of follicular lymphoma is based on the proportion of follicular areas as follows: follicular if >75 % follicular areas; follicular and diffuse if 25–75 % follicular areas; focally follicular if <25 % follicular areas; and diffuse if 0 % follicular areas [133]. Note that in small biopsy specimens, the lack of follicular areas may reflect inadequate sampling. Prominent sclerosis is another feature that can sometimes be seen within or between the neoplastic follicles [134, 135].

Fig. 12.8

Follicular lymphoma. The follicle lacks polarization of centrocytes and centroblasts, and the mantle zone is attenuated

The neoplastic lymphoid cells are composed of centrocytes and centroblasts. Centrocytes are small to medium in size with angulated, twisted or cleaved nuclei, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm. Centroblasts are large cells with round to oval nuclei, vesicular chromatin, 1–3 peripheral nucleoli, and a thin rim of cytoplasm [17]. Centrocytes typically predominate while the number of centroblasts varies and is the basis of grading. Follicular lymphoma is graded by counting the number of centroblasts in ten representative neoplastic follicles at 40× high-power field (hpf) and then calculating the average number of centroblasts/hpf. The average is then used to grade as follows: grade 1, if 0–5 centroblasts/hpf; grade 2, if 6–15 centroblasts/hpf; grade 3A, if >15 centroblasts/hpf with centrocytes present; and grade 3B, if >15 centroblasts/hpf with solid sheets of centroblasts [40, 136, 137]. The clinical relevance in determining the grade in follicular lymphoma is distinguishing grade 3 from grades 1–2 (see prognostic features below).

12.2.5.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes in follicular lymphoma are positive for pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5) and surface immunoglobulin with coexpression of BCL2, BLC6, and CD10 (classically), though CD10 can be reduced or negative in high-grade follicular lymphoma or with extrafollicular extension of the tumor cells [138]. Tumor cells are negative for CD5, CD23, CD43, and IRF4/MUM1 [17, 36, 38, 43, 139–145]. Follicular dendritic cell meshworks are highlighted by CD21 and/or CD23 [36]. BCL2 protein is generally positive, which is useful in distinguishing follicular lymphoma from follicular lymphoid hyperplasia. However, it is not useful in distinguishing follicular lymphoma from other low-grade B-cell lymphomas. Keep in mind that BCL2 is also expressed in normal T-cells and in B-cells of primary follicles and mantle zones [10, 17].

12.2.5.5 Flow Cytometry

12.2.5.6 Molecular Features

12.2.5.7 Prognostic Features

Prognosis is closely related to the grade of the disease at diagnosis [54, 151, 152]. Cases with more centroblasts (grades 3A and 3B) behave more aggressively and have a higher likelihood of progression to a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma than low-grade follicular lymphomas (grades 1 and 2) [129, 153–164]. Cases with concurrent t(14;18)(q32;q21) and t(8;14)(q24;q32) resulting in a fusion between the IGH and BCL2 genes and the MYC and IGH genes, respectively, are associated with an adverse prognosis [165, 166].

12.2.5.8 Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (see Sect. 12.1.1), hyaline vascular Castleman disease (see Sect. 12.1.2), chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with prominent proliferation centers (see Sect. 12.2.1), mantle cell lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.1), marginal zone lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.2), and nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.9).

12.2.6 Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Not Otherwise Specified

12.2.6.1 Definition

12.2.6.2 Clinical Findings

The median age at diagnosis is in the seventh decade, but with a wide age range. Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas are slightly more common in males than in females. Patients typically present with a rapidly enlarging tumor mass, which is site dependent based on areas of nodal or extranodal involvement. Most patients are asymptomatic, but when symptoms are present they, again, are dependent on the site of involvement [54, 59]. Most diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, not otherwise specified, arise de novo, but they can also represent a progression/transformation from a less aggressive, lower grade lymphoma. Immunodeficiency is a risk factor and these cases, compared to sporadic cases, are more commonly associated with EBV infection [167, 168]. In the liver, more than half of the cases of primary hepatic lymphoma are diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, not otherwise specified [169–171]. Chronic hepatitis C is an important risk factor [1].

12.2.6.3 Gross Findings

Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, not otherwise specified, are large, fleshy, white-to-yellow masses which infiltrate the liver parenchyma and can form single or multiple masses (Fig. 12.9).

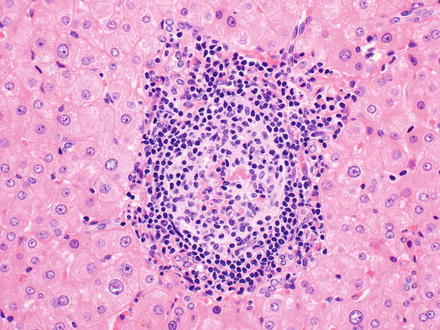

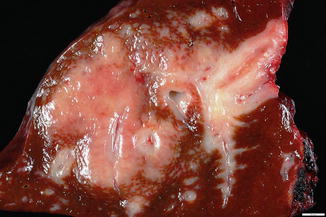

Fig. 12.9

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, gross. A white fleshy mass is seen

12.2.6.4 Microscopic Findings

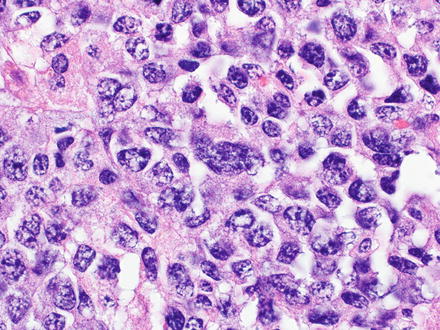

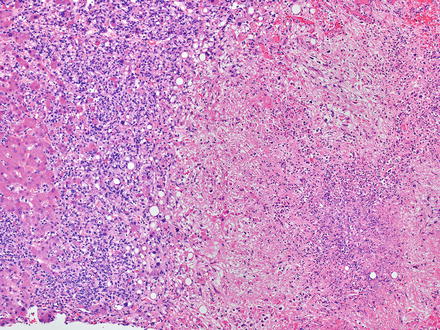

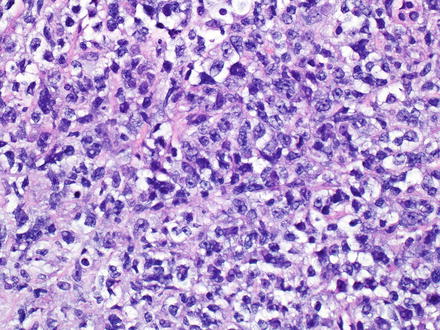

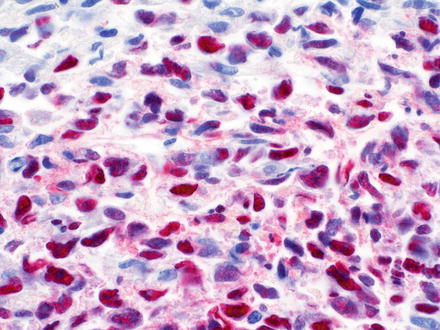

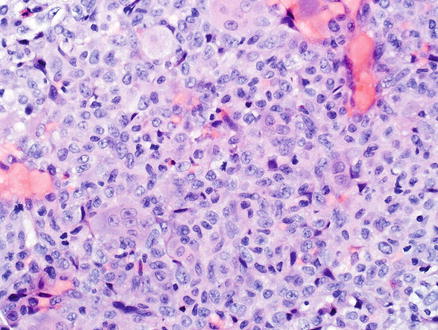

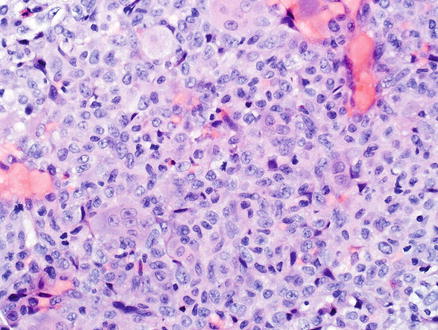

Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, not otherwise specified (NOS), efface the normal architecture of the liver with a diffuse (sheet-like) proliferation of large lymphoid cells (Fig. 12.10). Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas can also have hepatitis-like areas where tumor cells infiltrate the sinusoids [10]. There are three common morphological variants, which include centroblastic, immunoblastic, and anaplastic. The most common in primary liver lymphoma is the centroblastic variant, which is composed of medium to large lymphoid cells with round to oval nuclei, sometimes with irregular nuclear contours, vesicular chromatin, one to several membrane-bound nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm [40, 127, 172]. Typically this variant is polymorphic with an admixture of centroblasts and immunoblasts (which compose <90 % of the cells) [134, 173]. The immunoblastic variant is composed of large lymphoid cells with a single centrally located nucleolus and basophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm, which compose >90 % of the cells. The immunoblasts can sometimes have plasmacytic differentiation [40, 172, 174–176]. The anaplastic variant is composed of cells that are round to polygonal with large pleomorphic nuclei, which can have a cohesive growth pattern and mimic undifferentiated carcinoma [177]. It is also relatively common to have areas of sclerosis and necrosis. Immunodeficiency-associated cases are more commonly associated with EBV infection than sporadic cases (Figs. 12.11, 12.12, and 12.13).

Fig. 12.10

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. This case presented with a solid tumor mass. The cells are large with irregular nuclear profiles. Immunostains showed a non-germinal center B-cell phenotype

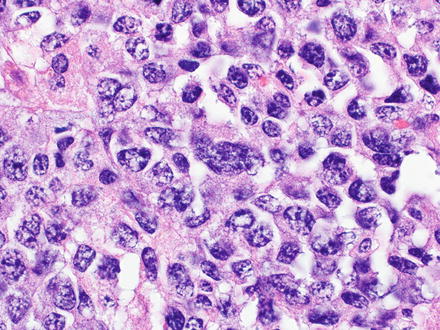

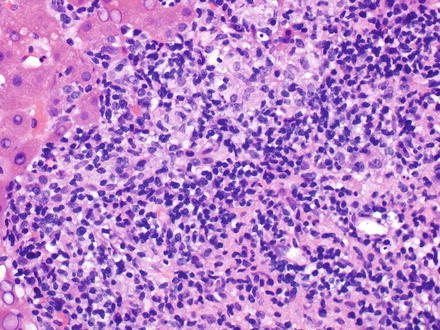

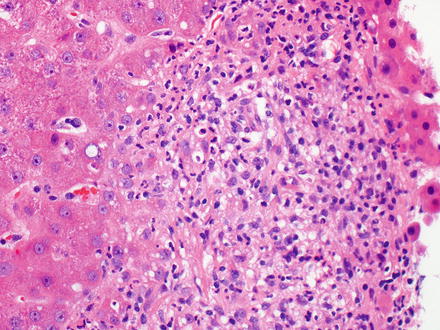

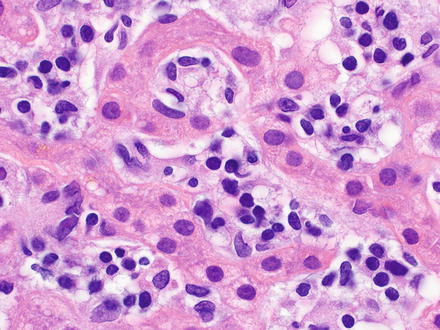

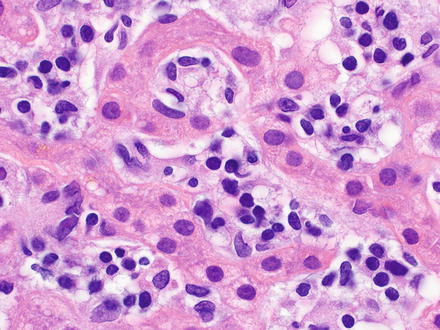

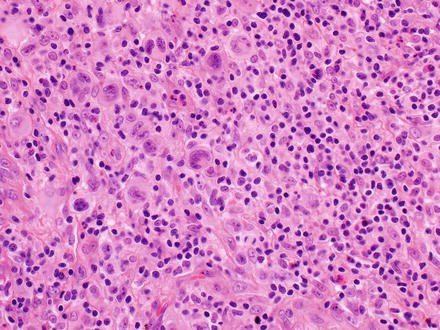

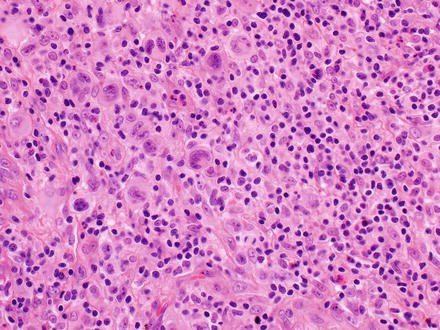

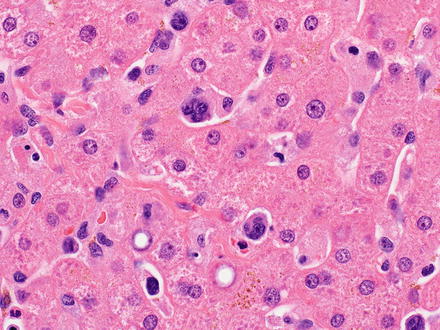

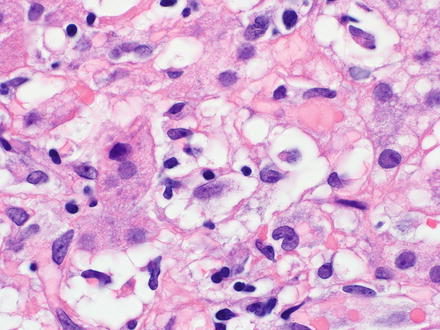

Fig. 12.11

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. This case developed secondary to long term immunosuppression therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. The lymphoma caused large areas of necrosis with secondary colonization by bacteria, leading to a submitted diagnosis of possible liver abscess

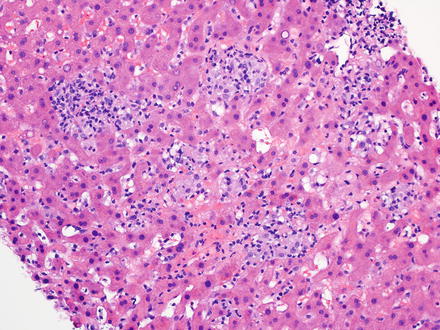

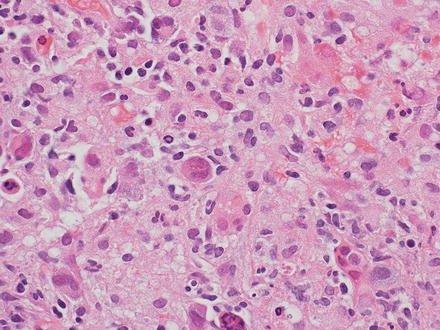

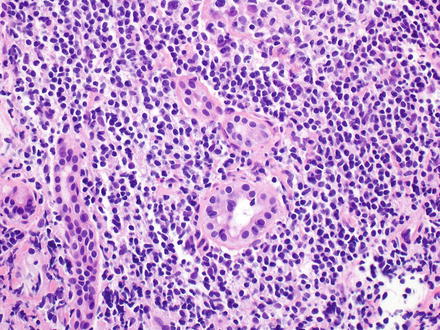

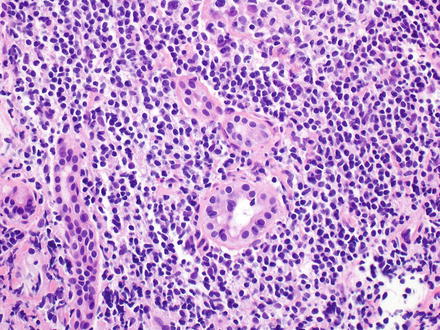

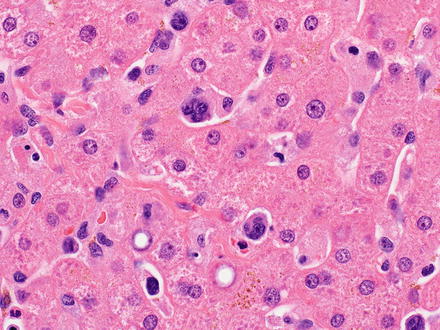

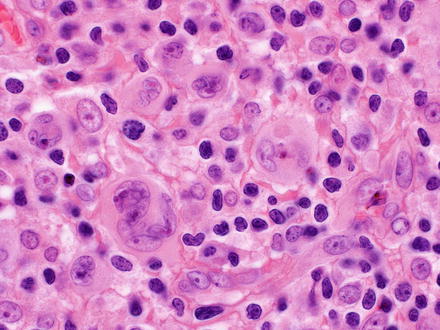

Fig. 12.12

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. This lymphoma arose in the setting of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Immunostains showed a non-germinal center B-cell phenotype

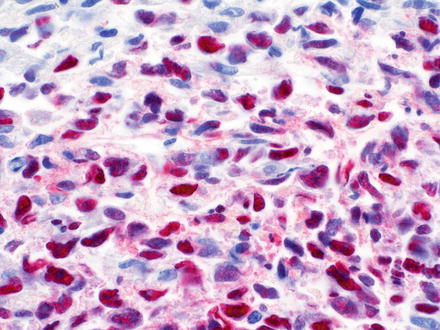

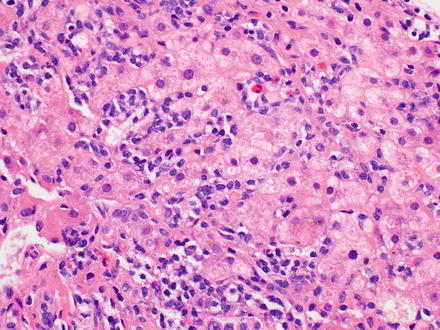

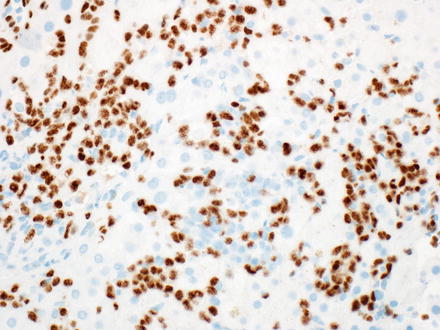

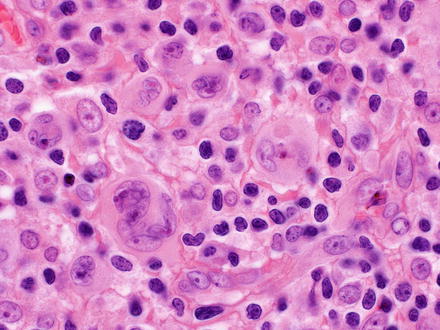

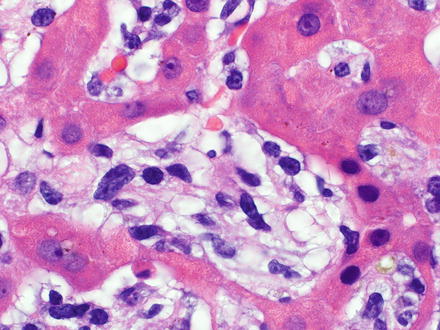

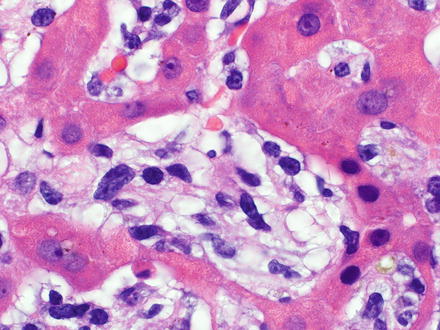

Fig. 12.13

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The lymphoma is strongly positive for Epstein–Barr virus encoded RNA (EBER) by in situ hybridization. Same case as the preceding image

12.2.6.5 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic B-cells are typically positive for pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5); however, they may lack one or more of these makers. They are also positive for surface and/or cytoplasmic immunoglobulin heavy chains in 50–75 % of cases [178]. CD5 expression is seen infrequently, but up to 40 % of cases can express CD10 [179–182]. CD30 may be positive, especially in the anaplastic variant [183]. The reported incidence of CD10, BCL6, and IRF4/MUM1 expression varies and is the basis for the Hans algorithm (see prognostic features below) [184–189]. Ki-67 (MIB-1) typically reveals a high cell proliferation fraction (usually >40 %) [190].

12.2.6.6 Flow Cytometry

Large lymphoma cells are fragile and typically lysed when subjected to flow cytometry. Therefore, flow cytometry is not typically indicated for the assessment of large-cell lymphomas.

12.2.6.7 Molecular Features

The most common translocation involves the BCL6 gene at 3q27, which can be observed in up to 30 % of cases [141, 191–205]. Translocation of the BCL2 gene at 18q21 (i.e., t(14;18)(q32;q21)) occurs in 20–30 % of cases [185, 195, 206]. MYC gene rearrangements have also been observed and are typically associated with a complex pattern of genetic alterations [185, 207].

12.2.6.8 Prognostic Features

Unfavorable clinical variables, according to the International Prognostic Index for aggressive lymphomas, include age >60 years, poor performance status (ECOG ≥ 2), advanced Ann Arbor stage (III–IV), extranodal involvement ≥2 sites, and high serum lactate dehydrogenase (> normal) [59]. The International Prognostic Index loses some of its predictive value in patients treated with rituximab [208], which has led to a significant improvement in prognosis [209]. Independent of the International Prognostic Index score, concordant bone marrow involvement by diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is associated with a very poor prognosis (5-year overall survival, 10 %). In contrast, discordant bone marrow involvement by low-grade B-cell lymphoma does not significantly influence the clinical outcome (5-year overall survival, 62 %) [210–212]. Some but not all studies have found that adverse prognosis is predicted by higher Ki-67 and by immunoblastic histology. A MYC translocation is associated with an unfavorable outcome [185] and cases with both BLC–2 and MYC translocations are associated with an extremely poor outcome [201, 213].

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can be divided into prognostically significant subgroups with germinal center B-cell-like, activated B-cell-like, or type 3 gene expression. Patients with the molecularly defined germinal center B-cell-like subtype have a significantly better clinical outcome than those with the activated B-cell-like or type 3 subtype [185, 214–216]. Similarly, the Hans algorithm uses CD10, BCL-6, and IRF4/MUM1 protein expression to subclassify diffuse large B-cell lymphoma into germinal center B-cell-like and non-germinal center B-cell-like subgroups. If ≥30 % of the neoplastic large B-cells express CD10, they are of the germinal center B-cell-like subgroup. If CD10 is negative, but BCL-6 is expressed in ≥30 % of the neoplastic large B-cells and IRF4/MUM1 is not, they are also of the germinal center B-cell-like subgroup. However, if CD10 and BCL-6 are both negative or if CD10 is negative but both BCL-6 and IRF4/MUM1 are expressed, they are of the non-germinal center B-cell-like subgroup. As with the molecularly defined subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, those of the germinal center B-cell-like subgroup by the Hans algorithm have a better clinical outcome than those with the non-germinal center B-cell-like subgroup [217].

12.2.6.9 Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes carcinoma, malignant melanoma, classical Hodgkin lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.9), and variants like T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma, EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly, and B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Carcinoma and malignant melanoma can be differentiated with the use of immunohistochemical stains. The neoplastic cells in a carcinoma should express keratin antigens while lacking expression of CD45 and pan-B-cell antigens. The neoplastic cells in malignant melanoma should express S-100, Melan A, and HMB45, while lacking expression of CD45 and pan-B-cell antigens.

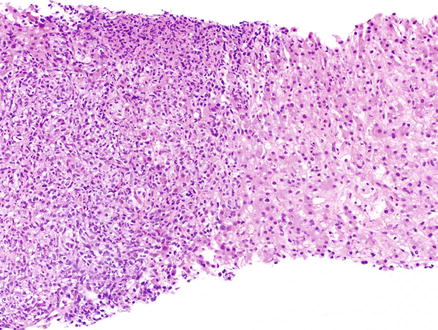

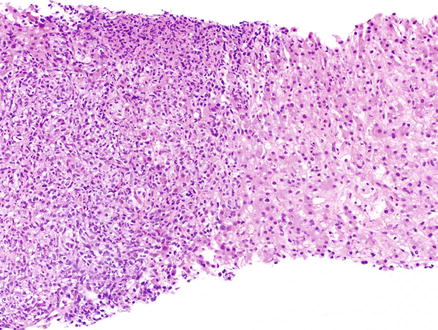

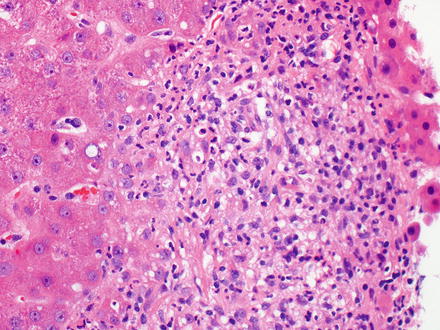

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma has rarely been reported as a primary tumor in the liver [218–220]. It mainly affects middle-aged men and patients usually present at advanced stage with fever, malaise, and hepatosplenomegaly [17, 221, 222]. In the liver, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma typically localizes to the portal tracts [223]. The portal tracts can be markedly expanded (Fig. 12.14) by an irregularly nodular infiltrate that is composed of scattered, single, large neoplastic B-cells embedded in a background of abundant small reactive T-cell lymphocytes and admixed histiocytes [17, 40, 224–226]. It is not uncommon to find the large B-cells within clusters of bland-looking, non-epithelioid histiocytes (Fig. 12.15) [227]. Eosinophils and plasma cells are usually not found. On needle core biopsy specimens, these histologic findings can mimic chronic hepatitis. The findings can also mimic granulomatous disease (Fig. 12.16). Careful observation for the presence of scattered large neoplastic cells is important [10]. The neoplastic B-cells have the same immunohistochemical profile as those seen in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, NOS. They are negative for CD15, CD30, and CD138. The background T-cell lymphocytes express CD3, CD5, CD8, and TIA-1 [221, 228] and the histiocytes express CD68 [17]. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma is considered an aggressive lymphoma [229, 230].

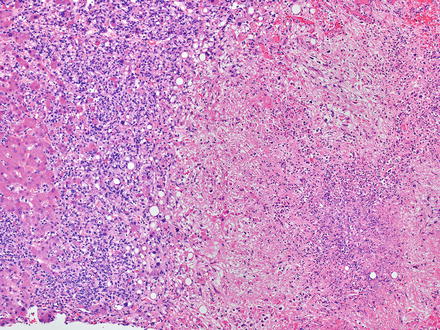

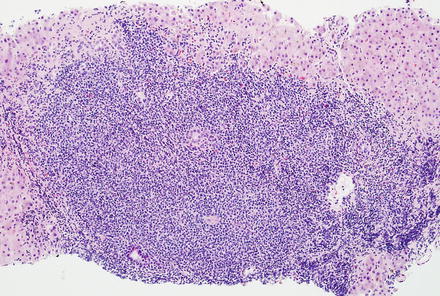

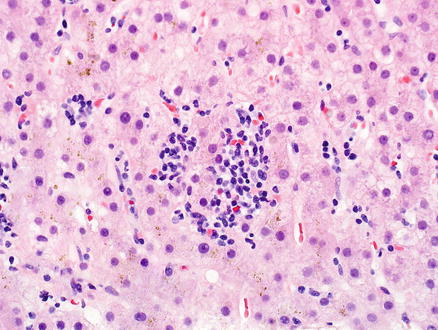

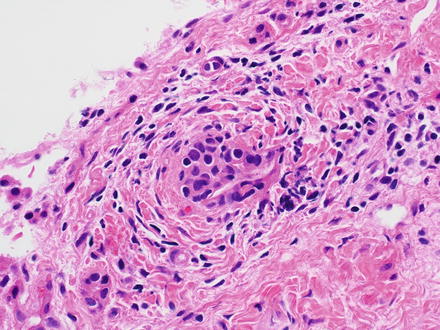

Fig. 12.14

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma. The portal tracts are markedly expanded

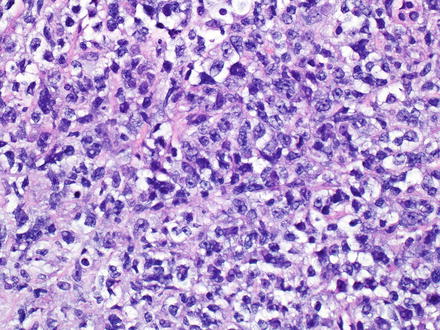

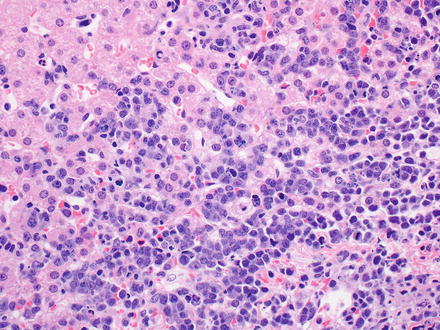

Fig. 12.15

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma. Clusters of bland-looking, non-epithelioid histiocytes can be seen

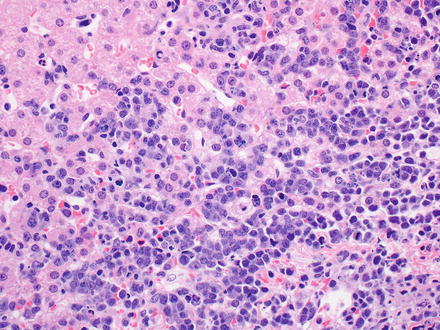

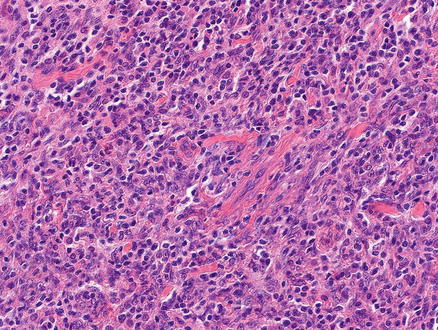

Fig. 12.16

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma. The lobular infiltrates had a granulomatous pattern

EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly is an EBV-positive clonal B-cell proliferation that occurs in patients >50 years of age who have no known immunodeficiency, immunosuppression, or prior lymphoma [17, 231, 232]. It is characterized by higher age distribution, higher stage at presentation, and an aggressive clinical course with a median survival of 2 years [17, 233]. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma effaces the normal architecture with a diffuse and polymorphic proliferation of varying numbers of large transformed cells/immunoblasts and Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg-like giant cells, often in a background of small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes. Two morphologic groups are recognized: a large-cell lymphoma and a polymorphic lymphoproliferative subtype. Large areas of geographical necrosis and angioinvasion can also be seen [10, 17]. The neoplastic B-cells are positive for CD20 and/or CD79a. CD10 and BCL-6 are usually negative, but IRF4/MUM1 is commonly positive. The large atypical cells are EBV-positive and express LMP-1 by immunohistochemical staining and/or EBER by in situ hybridization [231, 232]. They are also variably positive for CD30, but CD15 negative [10, 17, 233].

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma is, as the name implies, a B-cell lymphoma that has overlapping clinical, morphological, and/or immunophenotypic features between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma [17]. It is most common in males between the ages of 20–40 years [234, 235]. Patients present with a large anterior mediastinal mass which can lead to superior vena cava syndrome and/or respiratory distress. The pleomorphic neoplastic B-cells typically have a confluent, sheet-like growth pattern arising in a diffusely fibrotic stroma and a sparse reactive inflammatory infiltrate [234, 235]. Although pleomorphic cells resembling lacunar cells and Hodgkin cells comprise the majority of the infiltrate, a characteristic feature is the broad spectrum of cytological appearances of the neoplastic B-cells. Necrosis is also frequent. The neoplastic B-cells express pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5), CD45, and have coexpression of the Hodgkin lymphoma-associated markers CD15 and CD30. They also typically express OCT-2 and BOB-1. BCL-6 is variably expressed, while CD10 and ALK are generally negative [17, 234, 235]. Patients with B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, tend to have a poorer outcome [17].

12.2.7 Burkitt Lymphoma

12.2.7.1 Definition

Burkitt lymphoma is a medium-sized B-cell lymphoma with an extremely short doubling time that often presents in extranodal sites or like an acute leukemia. It has a highly characteristic, but not specific, translocation involving MYC at 8q24 [17].

12.2.7.2 Clinical Findings

Three clinical variants are recognized: endemic, sporadic, and immunodeficiency-associated Burkitt lymphoma. Burkitt lymphoma is very aggressive, but potentially curable, and is frequently seen in children [17, 236, 237]. Clinical presentation varies according to the epidemiologic subtype and the site of involvement. Patients often present with bulky disease and can have a leukemic phase. Endemic Burkitt lymphoma is seen in equatorial Africa, typically involves the jaws and other facial bones of young children (ages 4–7 years), and the majority of cases are associated with EBV infection [17, 238–241]. Endemic Burkitt lymphoma can also be associated with malaria infection [242]. Sporadic Burkitt lymphoma is seen throughout the world, commonly involves the abdominal cavity of older children, and a minority are associated with EBV infection [238, 241, 243]. Immunodeficiency-associated Burkitt lymphoma is primarily seen in association with HIV infection, often occurring as the initial manifestation of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and is associated with EBV infection in up to 40 % of cases [244–246]. Due to the high tumor burden, associated with the extremely short doubling time in Burkitt lymphoma, tumor lysis syndrome can occur upon initiation of therapy. Tumor lysis syndrome results from large numbers of dead tumor cells and leads to varying degrees of metabolic imbalance, with hypocalcemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperuricemia. These changes can further lead to acute renal failure.

12.2.7.3 Microscopic Findings

Burkitt lymphoma effaces the normal architecture of the liver with a monomorphic population of medium-sized lymphocytes (Fig. 12.17). The neoplastic cells can appear cohesive or have squared-off borders of retracted cytoplasm. Their nuclei are round with finely dispersed chromatin and multiple paracentrally situated nucleoli. Their cytoplasm is scant and amphophilic. Touch imprints stained with a Wright–Giemsa stain reveal neoplastic cells with deeply basophilic cytoplasm that usually contains lipid vacuoles. Abundant mitoses and apoptotic bodies are present. Numerous, scattered tingible-body macrophages typically impart a “starry sky” appearance in lymph nodes, but can be less prominent with liver involvement [10, 17, 172].

Fig. 12.17

Burkitt lymphoma. The tumor cells infiltrate the sinusoids and appear cohesive with scant basophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei are medium in size and round with finely dispersed chromatin

12.2.7.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes of Burkitt lymphoma are positive for pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5), with coexpression of CD10, BCL-6, and CD38, and aberrant expression of CD43. They are also positive for surface immunoglobulin heavy chain (usually IgM) [174, 241, 247]. They are negative for CD5, CD23, BCL-2 (weakly positive in up to 20 % of cases), CD138, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), and CD34 [17, 248–253]. Ki-67 (MIB-1) typically reveals nearly a 100 % cell proliferation fraction [174].

12.2.7.5 Molecular Features

Most cases of Burkitt lymphoma have a MYC translocation, though this translocation is not specific for Burkitt lymphoma. The t(8;14)(q24;q32) is classically observed, with fusion of the MYC and IGH genes [17, 254–256]. Other, less common MYC translocation partners (seen in up to 20 % of cases) include kappa, at 2p11, and lambda, at 22q11, immunoglobulin light chain genes [185, 249]. In the majority of Burkitt lymphoma cases, a MYC mutation is also identified [257–260].

12.2.7.6 Prognostic Features

12.2.8 Post-transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorders

12.2.8.1 Definition

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders are lymphoid or plasmacytic proliferations that develop as a consequence of immunosuppression in a recipient of a solid organ (i.e., liver, kidney, heart, and/or lung), bone marrow, or stem cell allograft and are most commonly associated with EBV infection. These proliferations may represent an EBV-driven infectious mononucleosis-type polyclonal proliferation or an EBV-positive, or negative, proliferation indistinguishable from a subset of B-cell (or less commonly T-cell) lymphomas that occur in immunocompetent individuals. Indolent B-cell lymphomas (i.e., follicular lymphoma or MALT lymphoma) in allograft recipients are excluded from this entity and are classified as they are in the normal host [17].

12.2.8.2 Clinical Findings

The clinical features of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders are highly variable and correlate with not only the type of allograft but also to a lesser extent the morphologically defined categories [17]. The frequency of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders varies among adult solid organ recipients (general incidence 1–5 %), and partly appears to correlate with the intensity of a patient’s immunosuppressive regimen [262–265]. The most important risk factor for EBV-driven post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders is EBV seronegativity at the time of transplantation [264, 266]. Sites of involvement include lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and liver [267–270]. In solid organ recipients, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder frequently involves the allograft, which may be clinically confused with rejection [262, 271]. Nonspecific features include malaise, lethargy, weight loss, fever, and lymphadenopathy. Organ-specific dysfunction is also common.

12.2.8.3 Microscopic Findings

Four morphological forms of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder are recognized: early lesions (plasmacytic hyperplasia and infectious mononucleosis-like post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder), polymorphic, monomorphic, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma type. Early lesions typically present in nodal tissue and the tonsils and are therefore not discussed here.

Polymorphic post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder is a morphologically polymorphous lesion that can involve the portal tracts, sinusoids, and/or efface the normal architecture of the liver and produce destructive extranodal masses (Fig. 12.18) [10, 272, 273]. A full range of B-cell maturation is observed, from immunoblasts to small and medium-sized lymphocytes with irregular nuclear contours to plasma cells. Areas of geographical necrosis, scattered large and atypical cells, and numerous mitoses can also be present. These lesions do not fulfill the criteria for any of the recognized types of lymphoma described in immunocompetent hosts.

Fig. 12.18

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. A large nodular infiltrate is seen in the portal tracts

Monomorphic post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder is a clonal neoplasm that fulfills the conventional criteria for one of the B-cell or T/NK-cell neoplasms that are recognized in the immunocompetent host. As stated above, the exceptions to this are the indolent B-cell lymphomas (i.e., follicular lymphoma or MALT lymphoma) in allograft recipients [274]. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma type post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder is almost always EBV-positive and fulfills the conventional criteria for classical Hodgkin lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.9) [17, 275, 276].

12.2.8.4 Immunohistochemical Features

In polymorphic post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, there is a mixture of B-cells (positive for the pan-B-cell antigen, CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5), which may or may not have immunoglobulin light chain restriction, and a variable number of reactive T-cells that will be positive for CD2, CD3, CD5, CD7, and CD43 [268, 277]. Most cases will also contain numerous cells positive for EBV by in situ hybridization [17].

The immunohistochemical features observed in monomorphic post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder will vary based on the type of neoplasm they resemble. EBV positivity is more variable in these cases. In classical Hodgkin lymphoma type post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, the immunohistochemical features are similar to classical Hodgkin lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.9) and EBV positivity is typical [17].

12.2.8.5 Prognostic Features

Early lesions (plasmacytic hyperplasia and infectious mononucleosis-like post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder) are more likely to regress with reduction in immune suppression than other forms of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder [278, 279]. Myelomatous lesions and T/NK-cell post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders are aggressive and less likely to regress with decreased immunosuppression. Although not reproduced in all studies, EBV negativity is thought to be an adverse prognostic indicator [280, 281]. Other prognostic factors associated with an adverse outcome include multiple sites of disease and advanced stage, older age at diagnosis, late onset of disease, high International Prognostic Index, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase [264, 281–284].

12.2.8.6 Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes allograft rejection and recurrent hepatitis C virus infection, especially on core needle biopsy. All of these entities may show a mixed portal inflammatory infiltrate, but the lymphocytes of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder are seen not only infiltrating the liver sinusoids, but also forming aggregates and nodules within the parenchyma. In addition, the inflammation in chronic hepatitis C and other inflammatory conditions is predominately T-cells and the sinusoidal infiltrates should not have any significant B-cell population. Positivity for EBV infection by in situ hybridization is also a very helpful diagnostic feature of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder over the other entities discussed here [10].

12.2.9 Hodgkin Lymphomas

12.2.9.1 Definition

Hodgkin lymphomas are lymphoid neoplasms, typically of B-cell origin, composed of two disease entities: nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma [285–291]. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma has four subtypes: nodular sclerosis (70 % of cases), mixed cellularity (20–25 %), lymphocyte-rich (5 %), and lymphocyte-depleted (<1 %) [17, 292–298].

12.2.9.2 Clinical Findings

Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma represents approximately 5 % of all Hodgkin lymphomas [297, 298]. Patients are typically 30- to 50-year-old males [299]. Individuals tend to be asymptomatic and present with localized peripheral lymphadenopathy (stage I or II), but 5–25 % present with advanced stage disease [17, 285, 296, 297, 299]. Progression to large B-cell lymphoma-like lesions occurs in 3–5 % of cases [300–303].

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma represents the other 95 % of all Hodgkin lymphomas. There is a bimodal age distribution, with the first peak at 15–35 years of age and the second peak later in life [304]. There is a male predominance in all subtypes, except for nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma, which develops in women at a rate equal to or greater than that seen in men [10]. EBV is postulated to play a role in the pathogenesis of classical Hodgkin lymphoma, in particular mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma and lymphocyte-depleted classical Hodgkin lymphoma [305]. B symptoms (fever, night sweats, and weight loss) are present in up to 40 % of patients. More than 60 % of patients have localized disease (stage I and II) and therefore typically present with peripheral lymphadenopathy of a single or contiguous lymph nodes. Nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma tends to involve the mediastinum while mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma commonly involves the abdomen and spleen [17]. Both mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma and lymphocyte-depleted classical Hodgkin lymphoma are more often associated with HIV infection [40, 296, 306–308].

12.2.9.3 Microscopic Findings

Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma effaces the normal architecture of the liver with a nodular or nodular and diffuse polymorphous infiltrate. The infiltrate is predominately composed of reactive small lymphocytes and epithelioid histiocytes with interspersed neoplastic lymphocyte predominant cells. Lymphocyte predominant cells (formerly called lymphocytic and/or histiocytic [L&H] cells) are large cells with a large, multilobated nucleus, multiple basophilic nucleoli, and scant pale cytoplasm. The extent to which their nuclei are folded can be extreme and is the basis for lymphocyte predominant cells also being known as “popcorn” cells [40, 309]. Classic Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells are rare or nonexistent in nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma [310]. The histiocytes can be singly distributed or in clusters. It’s important to remember that nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphomas can be found adjacent to, can proceed, or can follow progressive transformation of germinal centers, in which enlarged hyperplastic lymphoid follicles are disrupted and have intermingling of follicle center cells and mantle cells [17, 174, 285, 311, 312].

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma effaces the normal architecture of the liver with a polymorphous inflammatory cell-rich infiltrate admixed with a variable number of neoplastic lymphoid cells (Figs. 12.19 and 12.20). The composition of the non-neoplastic infiltrate varies according to the histological subtype, but is classically composed of small reactive lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, histiocytes, plasma cells, fibroblasts, and collagen fibers. The neoplastic lymphoid cells are composed of mononuclear Hodgkin cells and multinucleated Reed–Sternberg cells. Classical Reed–Sternberg cells are large binucleate cells with round to irregular nuclear contours, pale chromatin, a single prominent eosinophilic nucleolus, a perinuclear halo, and abundant basophilic cytoplasm. Mononuclear variants are termed Hodgkin cells. Sometimes the neoplastic cells are not the prototypic Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells [17].

Fig. 12.19

Hodgkin lymphoma, classical type. This portal tract has a polymorphous inflammatory cell-rich infiltrate

Fig. 12.20

Hodgkin lymphoma, classical type. Reed–Sternberg cells are seen

Nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by collagen bands that surround at least one nodule and Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells with lacunar type morphology [17, 309]. In formalin-fixed tissues, the cytoplasm of the Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells can show retraction of the cytoplasmic membrane so that the cells seem to be sitting in lacunae, and thus have been termed lacunar cells [313]. Association with EBV is less frequent (10–40 %) than in mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma [17, 314–317].

Mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by scattered classical Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells in a diffuse or vaguely nodular mixed inflammatory background without broad bands of fibrosis as seen in nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Additionally, cases that do not fit into the other subtypes are by default put into this category [17, 309]. Association with EBV is much more frequent (~75 %) than in nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma and lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma [285].

Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by scattered Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells with an overall nodular, or rarely a diffuse, growth pattern [285]. The nodules are composed predominately of small reactive B-cell lymphocytes, with or without eccentrically located germinal centers, and admixed Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells within the nodules but outside of the germinal centers. Eosinophils and/or neutrophils are absent from the nodules. Association with EBV is seen more frequently than in nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma but less frequently than in mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma [17, 285, 318].

Lymphocyte-depleted classical Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by a diffuse growth pattern that is rich in Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells and/or depleted in non-neoplastic lymphocytes (with a predominance of Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells relative to the background lymphocytes). Cases can have pleomorphic Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells, giving the neoplasm a sarcomatous appearance [17, 309]. Other cases can have diffuse fibrosis, but not a nodular sclerosing fibrosis pattern as seen in nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma. This subtype is often associated with HIV infection [307, 308] and most HIV-positive cases are also infected with EBV [319–321].

12.2.9.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The classical architectural background in nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is nodular meshworks of CD21/CD23-positive follicular dendritic cells, which are predominately filled with small reactive B-cells and numerous CD4/CD57-positive T-cells [322]. Within these nodules are the lymphocyte predominant cells that are neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes, which are positive for CD20, CD79a, PAX-5, BCL-6, and CD45 and coexpress OCT-2 and BOB-1 [285, 323–327]. Lymphocyte predominant cells are positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) in more than 50 % of cases [285, 328] and IgD in 9–27 % of cases [329–331]. Classically, lymphocyte predominant cells lack expression of CD15 and CD30 and are ringed by T-cells, which express CD3, CD4, and CD57 [10, 17]. EBV positivity is typically not seen in nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma [10].

In classical Hodgkin lymphoma, the Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells are positive for CD30 in nearly all cases [332–334] and CD15 in the majority (75–85 %) of cases [334–336] and are usually negative for CD45 [328, 337–339]. CD30 and CD15 staining shows not only membranous staining, but also has a perinuclear accentuation of the Golgi complex. Typically the Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells are negative for CD20 and CD79a. Their B-cell nature is demonstrated by expression of PAX-5 in 95 % of cases [340], which interestingly is typically weaker than that of the surrounding reactive B-cells [341]. Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells rarely express EMA and usually do not coexpress OCT-2 or BOB-1 [178]. The prevalence of EBV in Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells varies according to the histological subtype with the highest frequency found in mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma (up to 75 %) and the lowest in nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma (10–40 %) [342]. EBV-infected Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells express Epstein–Barr virus Latency Membrane Protein 1 (LMP1) [10, 343].

12.2.9.5 Molecular Features

12.2.9.6 Prognostic Features

The prognosis of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma is dependent upon the stage, with advanced stages of disease having an unfavorable prognosis [286, 288, 304]. The prognosis of classical Hodgkin lymphoma is dependent on both clinical and laboratory parameters [348], while the histologic subtype is less important [292, 349]. HIV-positive patients present at a higher stage (stage III or IV) and progress in a more aggressive fashion [350].

12.2.10 Other B-Cell Lymphomas

Other B-cell lymphomas that can also involve the liver, and will be discussed briefly in the following paragraphs, include splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma, plasma cell neoplasms, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, ALK-positive large B-cell lymphoma, and plasmablastic lymphoma.

Splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma is a provisional entity in the 2008 edition of the WHO Classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues and involved the liver in up to 18 % of cases in one study [351]. It is an uncommon lymphoma, which typically presents with massive splenomegaly and a relatively low lymphocytosis [17, 351]. The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes are monomorphic small to medium-sized with round nuclei, vesicular chromatin, occasional small nucleoli, and a pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm with plasmacytoid features. Splenic histology may be essential for the diagnosis where a diffuse pattern of involvement of the splenic red pulp is seen [17, 351]. The neoplastic B-cells are positive for CD20, IgG, and DBA.44. They are negative for CD5, CD10, CD11c, CD23, CD25, CD103, CD123, and Annexin-1 [352–354]. Splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion in which you should rule out a differential diagnosis that includes CLL/SLL (see Sect. 12.2.1), splenic marginal zone lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.2), hairy cell leukemia (see Sect. 12.2.3), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.4), prolymphocytic leukemia, and hairy cell leukemia-variant [17, 351, 355, 356].

Plasma cell neoplasms are proliferations of clonal immunoglobulin producing cells. The neoplastic cells are generally plasma cells or plasmacytoid lymphocytes and they secrete a single monoclonal immunoglobulin called a paraprotein or M-protein. The diagnosis of these disorders is based on a combination of morphologic, immunologic, and radiographic features, combined with the clinical presentation [10, 17]. Plasma cell myeloma can involve the liver [357, 358] and in theory, the liver could also be the primary site of involvement by an extraosseous plasmacytoma. Liver involvement can show sinusoidal and portal infiltrates of neoplastic plasma cells (Fig. 12.21). Mature plasma cells have eccentric, round nuclei with condensed chromatin, classically in a clock-face distribution, a perinuclear hof (clearing), and abundant basophilic cytoplasm. However, in some cases the plasma cell morphology may be difficult to appreciate (see Fig. 12.21). Like normal plasma cells, neoplastic plasma cells express CD38, CD138, and MUM-1 (Fig. 12.22). CD138 does not work as well to identify plasmacytic differentiation on liver specimens, because CD138 also stains the background hepatocytes. In contrast to normal plasma cells, the tumor cells will express monotypic cytoplasmic immunoglobulin light chains, almost always be CD19 negative, and 67–79 % will aberrantly coexpress CD56 [359–361]. The differential diagnosis includes reactive plasmacytosis, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.4), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with plasmacytoid features (see Sect. 12.2.6). Monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition diseases are closely related disorders characterized by visceral and soft tissue deposition of immunoglobulin resulting in compromised organ function [17]. Specific types of monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease with known liver involvement include primary amyloidosis and monoclonal light and heavy chain deposition diseases [17].

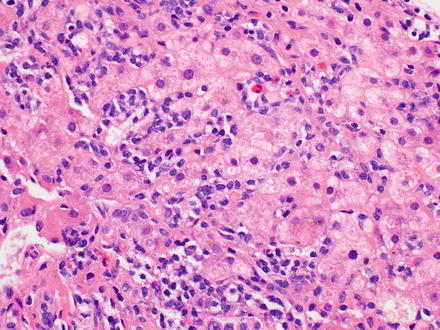

Fig. 12.21

Plasmacytoma. The biopsy shows an atypical lymphoid infiltrate involving the lobules. The plasmacytic nature of the neoplastic cells is not readily apparent on the H&E

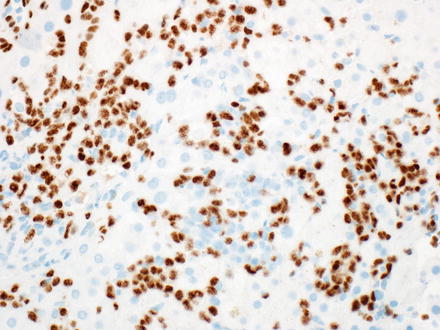

Fig. 12.22

Plasmacytoma, MUM1. The neoplastic cells are easily identified on MUM1 immunostain

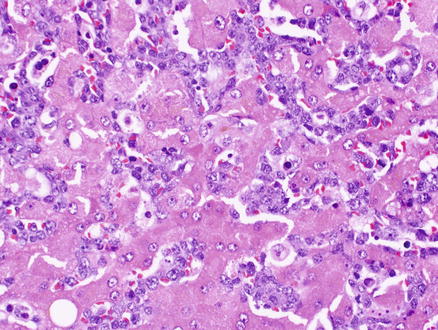

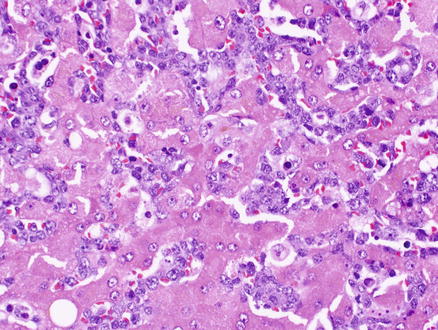

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is a large B-cell lymphoma characterized by selective growth of neoplastic cells within the lumina of vessels, particularly capillaries [17, 40, 362, 363]. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is an aggressive lymphoma with two general patterns, a Western form and an Asian variant. The Western form has a nonspecific clinical presentation based on the organs involved. The Asian variant tends to present with multiorgan system failure, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, and hemophagocytic syndrome [364–369]. The neoplastic large B-cell lymphocytes have prominent nucleoli with frequent mitotic figures and are mainly found in the lumina of small or intermediated-sized vessels in many organs. A sinusoidal pattern of distribution is observed when there is liver involvement (Fig. 12.23) [17, 370]. The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes express pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5), with or without coexpression of CD5 and/or CD10 [17].

Fig. 12.23

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. A dense atypical infiltrate of neoplastic B-cells fills the sinusoids

ALK-positive large B-cell lymphoma is a neoplasm of monomorphic large immunoblast-like B-cells that express ALK [17]. ALK-positive large B-cell lymphoma is also a very aggressive lymphoma. Patients present at an advanced stage (III/IV) of disease and can have liver involvement [371]. The neoplastic large B-cells are a monomorphic population of immunoblast-like cells with round nuclei, pale chromatin, large central nucleoli, and abundant cytoplasm, which can have plasmablastic differentiation [17, 372, 373]. The neoplastic B-cell lymphocytes rarely express pan-B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX-5), do not express CD30, and have weak to negative CD45 expression. Characteristically they strongly express EMA and the plasma cell markers CD38, CD138, and MUM-1 [372–377]. Most cases express monotypic cytoplasmic immunoglobulin light chains [372]. By definition, the neoplastic cells are strongly positive for ALK, most commonly with a restricted granular cytoplasmic staining pattern highly indicative of the t(2;17)(p23;q23), resulting in the fusion of the ALK and clathrin heavy chain (CLTC) genes [373, 378–383]. A few cases have been observed to have the t(2;5)(p23;q35), resulting in the fusion of the ALK and nucleophosmin (NPM) genes, which produces a cytoplasmic, nuclear, and nucleolar ALK staining pattern. The differential diagnosis includes acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (see Sect. 12.4), anaplastic variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.6), plasmablastic lymphoma, and plasmablastic myeloma [371].

Plasmablastic lymphoma is an aggressive large B-cell lymphoma in which most of the neoplastic cells resemble B-cell immunoblasts and all of the neoplastic cells have the immunophenotype of plasma cells [17]. Two clinical presentations are observed in plasmablastic lymphoma. The most common presentation is a mass in the oral cavity of an HIV-positive young male. The other presentation is outside the oral cavity (which can rarely involve the liver) in an HIV-negative older male, with another type of immunodeficiency, or in elderly patients [10, 384–387]. The neoplastic cells can have a morphological spectrum varying from large immunoblast-like cells to cells with plasmacytic differentiation. Mitoses are frequently identified. The neoplastic B-cells express a plasma cell phenotype with reactivity for CD38, CD138, and MUM-1. CD79a, EMA, and CD30 are also frequently expressed. CD56 may be expressed in cases with plasmacytic differentiation. However, tumor cells are negative to only weakly positive for CD20, PAX-5, and CD45. Most cases are EBV-positive, with nearly 100 % EBV positivity in the oral mucosal type, while HHV-8 is consistently negative [10, 17, 384, 385, 387–390]. The differential diagnosis includes anaplastic or plasmablastic plasma cell myeloma and plasmacytomas, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, NOS (see Sect. 12.2.6), Burkitt lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.7), poorly differentiated carcinomas, and malignant melanomas [10, 17, 387].

12.3 T-Cell Lymphomas

12.3.1 Adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma

12.3.1.1 Definition

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is a peripheral T-cell neoplasm typically composed of highly pleomorphic lymphoid cells and caused by the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) [17].

12.3.1.2 Clinical Findings

The distribution of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is linked to the prevalence of HTLV-I and is endemic in southwestern Japan, the Caribbean basin, New Guinea, and parts of Central Africa and South America [10, 17]. There is usually a long latency period of several decades before clinical features appear [391]. The average age of onset is 58 years (range is 20–80 years) and the male-to-female ratio is 1.5:1 [392, 393]. The distribution of disease is usually systemic, and therefore patients present with wide-spread lymph node and peripheral blood involvement, as well as involvement of extranodal sites (i.e., the liver and most commonly, the skin) [17, 394]. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma has multiple clinical presentations: acute, lymphomatous, chronic, and smoldering. Cutaneous lesions are common in all. Hypercalcemia, with or without lytic bone lesions, is most commonly seen in the acute presentation. Many patients will have an associated T-cell immunodeficiency with frequent opportunistic infections [17, 395].

12.3.1.3 Microscopic Findings

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma effaces the normal architecture of the liver with a broad cytologic spectrum of neoplastic cells. The known morphological variants are: pleomorphic small, medium, and large cell types, anaplastic, and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma-like [396]. Typically, the neoplastic T-cells are medium to large-sized with coarsely clumped chromatin, distinct nucleoli, and nuclear pleomorphism. Blast-like cells with more dispersed chromatin are variably present [395]. Other cases may be composed of small lymphocytes with irregular nuclear contours or giant cells with convoluted and multilobated nuclei [17]. Still, other cases may exhibit a classical Hodgkin lymphoma-like histology [397] with EBV-positive B-cells having Hodgkin-like features interspersed in a background of small to medium-sized lymphocytes with irregular nuclear contours. In the peripheral blood, the neoplastic cells have a polylobated appearance, sometimes with a cloverleaf shape, and have been termed “flower cells” [10, 17].

12.3.1.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic T-cells express the T-cell antigens CD2, CD3, and CD5, but usually are negative for CD7. In most cases, the T-cells are CD4-positive and CD8-negative. They also typically express markers that are features of regulatory T-cells, which include CD25 (expressed in almost all cases), CCR4, and FOXP3 [398]. Larger transformed cells may be positive for CD30 but will be negative for ALK and cytotoxic T-cell markers (TIA-1 and Granzyme B) [17, 399].

12.3.1.5 Prognostic Features

12.3.1.6 Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL, NOS) (see Sect. 12.3.3).

12.3.2 Hepatosplenic T-Cell Lymphoma

12.3.2.1 Definition

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma is an extranodal and systemic neoplasm derived from cytotoxic T-cells, usually of the γδ T-cell receptor type [17].

12.3.2.2 Clinical Findings

The median age at diagnosis is 35 and there is a male predominance [402, 403]. Up to 20 % of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphomas arise in the setting of chronic immune suppression [402, 404–406]. Patients typically present with hepatosplenomegaly, but not lymphadenopathy, and systemic symptoms [402, 403, 407–410]. They also typically have marked thrombocytopenia, often with anemia and leukopenia [402, 403, 408].

12.3.2.4 Microscopic Findings

In the liver, there is typically a sinusoidal infiltration by a monomorphic population of medium-sized lymphocytes (Fig. 12.24) [402, 403, 408]. The portal tracts can also be involved (Fig. 12.25). The medium-sized lymphocytes have regular nuclei with loosely condensed chromatin, small inconspicuous nucleoli, and a pale rim of cytoplasm [403]. Cytological atypia with large cell or blastic changes may be seen, especially with disease progression [17, 402, 408, 411].

Fig. 12.24

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. The sinusoids are infiltrated by medium-sized lymphocytes that have regular nuclei with loosely condensed chromatin, small inconspicuous nucleoli, and a pale rim of cytoplasm

Fig. 12.25

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. The portal tracts were also involved in this case

12.3.2.5 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic T-cells in hepatosplenic T-cell lymphomas express the T-cell antigens CD2, CD3, and CD7, but are usually negative for CD5. The T-cells can express CD56 and are typically negative for both CD4 and CD8. Most cases are of the TCRγδ type and express TCRδ1 and are negative for TCRαβ [402, 412]. However, a minority of the cases are of the TCRαβ type [410, 413]. The neoplastic T-cells have a nonactivated cytotoxic T-cell phenotype with expression of the cytotoxic granule-associated protein TIA-1, but not Granzyme B [17, 403, 414, 415].

12.3.2.6 Cytogenetic Features

12.3.2.7 Prognostic Features

The clinical course is aggressive with median survival of <2 years and relapses are seen in the vast majority of cases that do initially respond to chemotherapy [402].

12.3.3 Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma, Not Otherwise Specified

12.3.3.1 Definition

This is a heterogeneous category of mature T-cell lymphomas that do not correspond to any of the specifically defined entities of mature T-cell lymphomas in the current WHO Classification [17].

12.3.3.2 Clinical Findings

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, most commonly presents in adults and has a male-to-female ratio of 2:1 [17]. Patients typically present with generalized peripheral lymphadenopathy, with the potential of any site being affected. The majority of patients have advanced disease with B symptoms. Paraneoplastic features also may be seen, such as eosinophilia, pruritus, and/or rarely hemophagocytic syndrome [418].

12.3.3.3 Microscopic Findings

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, effaces the normal architecture of the liver with a diffuse lymphoid infiltrate that can have a spectrum of cytologic features, which include highly polymorphic to monomorphic forms. The neoplastic T-cells are medium to large cells with irregular, pleomorphic nuclei that have hyperchromatic or vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and abundant mitotic figures. The portal tracts can have large nodular infiltrates (Fig. 12.26) while the lobular changes can mimic hepatitis (Fig. 12.27). Clear cells and Reed–Sternberg-like cells can be seen and high endothelial venules may be increased [174, 419, 420]. The neoplastic T-cells are typically present in an inflammatory background composed of small lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, large B-cells, and clusters of epithelioid histiocytes [17, 421].

Fig. 12.26

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. The portal tracts have larger nodular aggregates of neoplastic T-cells

Fig. 12.27

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. The lobules have smaller foci that mimic hepatitis

12.3.3.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic T-cells are characterized by an aberrant T-cell phenotype defined by the loss of a pan-T-cell antigen. The typical aberrant phenotype observed is the expression of CD2 and CD3, with downregulation of CD5 and CD7. In most cases, the T-cells are CD4-positive and CD8-negative and usually express the TCR beta-chain (TCRβF1). However, cases that are CD4/CD8 double-positive or double-negative and cases that have a CD8, CD56, and cytotoxic granule expression have been observed [422]. Unlike angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS usually lacks a follicular T helper phenotype (they do not express CD10, BCL-6, CD279 [PD1], or CXCL13) [422–425].

12.3.3.5 Prognostic Features

12.3.3.6 Differential Diagnosis

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified is a diagnosis of exclusion. You must first rule out other specifically defined mature T-cell lymphomas including adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (see Sect. 12.3.1), angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (see Sect. 12.3.4), anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (see Sect. 12.3.5), and T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.10).

12.3.4 Angioimmunoblastic T-Cell Lymphoma

12.3.4.1 Definition

12.3.4.2 Clinical Findings

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma occurs in middle-aged and elderly adults, with an equal male-to-female ratio [428]. Patients typically present at an advanced stage of disease with generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, B symptoms, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia [428–431]. Patients also frequently present with a skin rash [17]. They can develop immunodeficiency secondary to the neoplastic process and, consequently, cases are commonly associated with EBV infection [432, 433].

12.3.4.3 Microscopic Findings

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma effaces the normal architecture of the liver with a polymorphic infiltrate composed of neoplastic T-cells admixed with small reactive lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, and epithelioid histiocytes. The neoplastic T-cells are small to medium-sized with round nuclei, abundant clear to pale cytoplasm, and a distinct cell membrane. In the background there is a marked proliferation of arborizing high endothelial venules, frequently accompanied by an increase in follicular dendritic cell meshworks that surround the high endothelial venules, and an expansion of B-cell immunoblasts. The neoplastic T-cells can be seen forming small clusters around the high endothelial venules [17, 428, 434, 435].

12.3.4.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic T-cells express pan-T-cell antigens (CD2, CD3, CD5, and CD7) and in the majority of cases are CD4-positive. The neoplastic cells characteristically have the phenotype of normal follicular helper T-cells and thus express CD10, BCL-6, PD1, and CXCL13 in 60–100 % of cases [388, 423, 424, 436–441]. Background reactive T-cells are often CD8 positive. CD21 and CD23 highlight the increase in follicular dendritic cell meshworks. B-cell immunoblasts and plasma cells are polytypic, with the former revealing a subset that are EBV-positive [17, 436].

12.3.4.5 Cytogenetic Features

12.3.4.6 Prognostic Features

12.3.5 Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma

12.3.5.1 Definition

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma is a T-cell lymphoma consisting of large, pleomorphic lymphoid cells, often with horseshoe-shaped nuclei, abundant cytoplasm, and expression of CD30. Two subsets of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma are recognized: one with a translocation involving the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene and expression of the ALK protein (ALCL, ALK+), the other lacking these features (ALCL, ALK−) [10, 17, 40, 334].

12.3.5.2 Clinical Findings

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK+ is most common in the first three decades of life and has a male predominance [17, 445, 446]. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− has a peak incidence in adults 40–65 years of age and also has a male predominance [447, 448]. Both subtypes of patients tend to present at an advanced stage of disease with peripheral lymphadenopathy, often accompanied by extranodal and bone marrow involvement and B symptoms [334, 446, 449–451]. Extranodal sites of involvement are less commonly seen in the anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− subtype [17].

12.3.5.3 Microscopic Findings

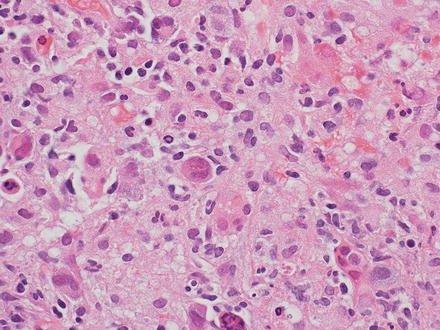

Typically the involved tissue is infiltrated by a lymphoid neoplasm that has a diffuse and cohesive growth pattern (Fig. 12.28) with a broad morphologic spectrum [174, 445, 452–456]. In the liver, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma can also have a portal pattern of infiltration that can lead to destruction of the portal structures [10]. The tumor can also grow as a mass lesion or can infiltrate the sinusoids (Fig. 12.29). The morphologic spectrum can be extreme and ranges from a small cell neoplasm to very large cells with abundant cytoplasm [17]. In all morphologic variants, there is a variable proportion of neoplastic cells that are large in size with the characteristic eccentric, horseshoe-, or kidney-shaped nuclei, which have been referred to as “hallmark cells” (Fig. 12.30) [445]. Their nuclear chromatin can be finely clumped or dispersed, with multiple small, basophilic nucleoli and they tend to have a perinuclear eosinophilic region. Other neoplastic cells can have multiple nuclei that form a wreath-like pattern. The neoplastic hallmark cells tend to concentrate around blood vessels [17, 445]. The neoplastic cells in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− are often larger, more pleomorphic, and/or have an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio compared to those seen in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK+ [446, 457–459].

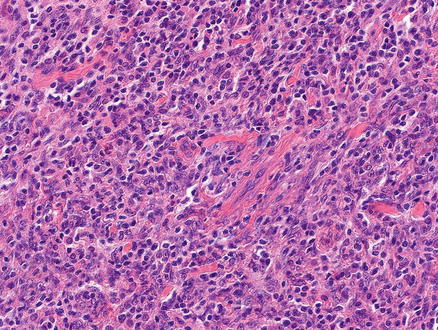

Fig. 12.28

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. The tumor is growing as a solid mass

Fig. 12.29

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. The tumor is growing as markedly atypical cells in the sinusoids

Fig. 12.30

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. “Hallmark” cells are seen, with eccentric and kidney-shaped nuclei

12.3.5.4 Immunohistochemical Features

The neoplastic T-cells are characterized by an aberrant T-cell phenotype due to the loss of several pan-T-cell antigens. However, the majority of cases do express one or more of the T-cell antigens (CD2, CD3, CD5, or CD7) [445, 460]. CD3 is negative in greater than 75 % of cases [445, 461] and therefore, CD2 or CD5 are more useful T-cell antigens to establish lineage of the neoplastic cells. In most cases, the neoplastic T-cell lymphocytes are CD4-positive, CD8-negative, and have an activated cytotoxic T-cell phenotype with expression of the cytotoxic granule-associated proteins TIA-1 and Granzyme B [327, 460, 462]. The neoplastic cells are positive for CD30 with both a membranous staining pattern and accentuation of the perinuclear Golgi region, with the strongest immunoreactivity observed in the larger cells [334]. CD30 staining should be diffuse and equally strong in all cells to help distinguish anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− from other peripheral T-cell lymphomas, which can focally express CD30 with variable intensity. ALK positivity is the defining feature of the anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK+ subtype and is absent in the anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− subtype (see molecular features below for unique staining patterns) [17]. The majority of cases have at least a proportion of neoplastic cells that are positive for EMA (less so in the anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− subtype) [445, 450, 453].

12.3.5.5 Molecular Features

The defining feature of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK+ is a translocation involving the ALK gene, leading to aberrant expression of the ALK protein. Different chromosomal translocations have been identified, all of which result in the fusion of the ALK gene to various partner genes [448, 463–467]. The vast majority of the anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK+ cases have a diffuse cytoplasmic staining pattern for ALK, but the distribution of the staining pattern can vary depending on the translocation [445, 448, 454, 468]. The two most common genetic alterations are t(2;5)(p23;q35) resulting in the fusion of the ALK and nucleophosmin (NPM) genes (60–84 % of cases) and t(1;2)(p25;p23) resulting in the fusion of the tropomyosin 3 (TPM3) and ALK genes (13 % of cases) [17, 469–473]. These two translocations also have a unique staining pattern for the ALK protein with the t(2;5)(p23;q35), showing both nuclear and diffuse cytoplasmic staining [445, 448, 454, 474], while the t(1;2)(p25;p23) shows diffuse cytoplasmic staining with peripheral intensification. The other unique staining pattern for the ALK protein is granular cytoplasmic staining that is observed in the t(2;17)(p23;q23), resulting in the fusion of the ALK and clathrin heavy chain (CLTC) genes [17].

12.3.5.6 Prognostic Features

Historically, patients with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK+ have been described as having a more favorable prognosis that anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− patients [446, 457, 459, 475, 476]. However, a recent study divided anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− patients into two groups: those with a DUSP22 rearrangement and those with a TP63 rearrangement (mutually exclusive rearrangements that were not observed in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK+ patients). Patients who had anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− with a DUSP22 rearrangement had an equivalent, if not a slightly better, 5-year overall survival rate compared to anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK+ patients. On the contrary, patients who had anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK− with a TP63 rearrangement had a very poor 5-year overall survival rate. Those patients with anaplastic large-cell lymphomas that lacked all three genetic markers had overall 5-year survival rates that fell in between [477].

12.3.5.7 Differential Diagnosis

A rare form of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with immunoblastic/plasmablastic features and ALK positivity is in the differential of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.10). This form of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma also expresses EMA, like anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, however the ALK staining shows a characteristic cytoplasmic-restricted granular pattern and they lack expression of CD30 [372]. The differential diagnosis also includes classical Hodgkin lymphoma (see Sect. 12.2.9), peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS (see Sect. 12.3.3), other subtypes of CD30-positive B- or T-cell lymphomas, and histiocytic sarcoma (see Sect. 12.5.1) [378, 478].

12.3.6 Other T-Cell and NK-Cell Lymphomas