Glandular Lesions

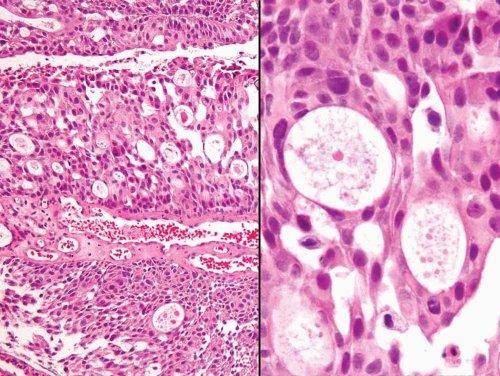

CYSTITIS GLANDULARIS (INTESTINAL TYPE)

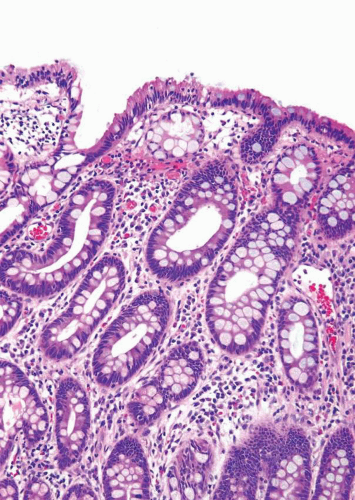

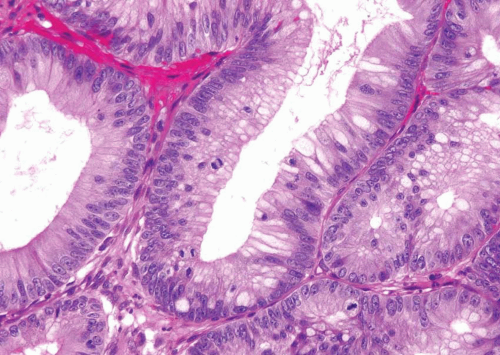

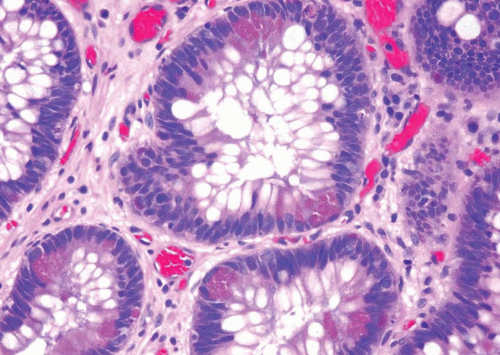

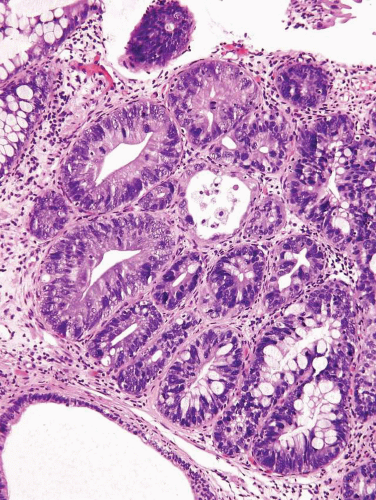

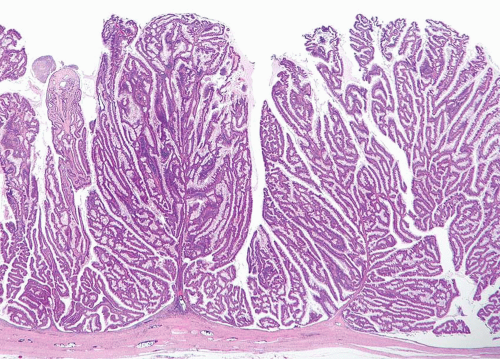

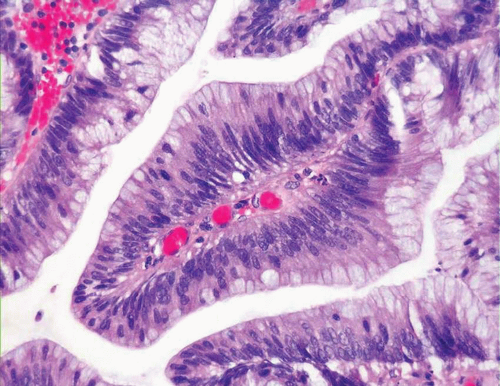

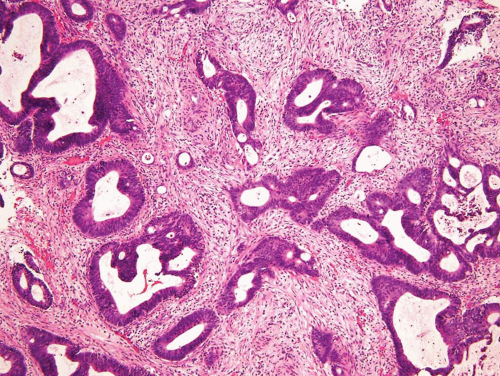

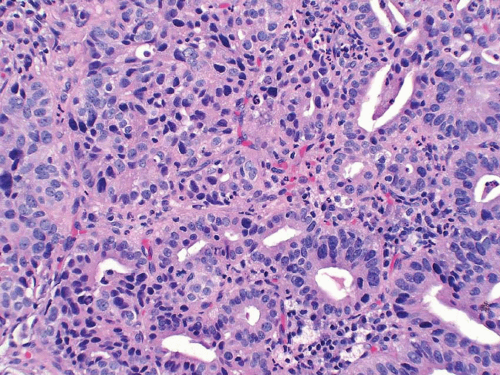

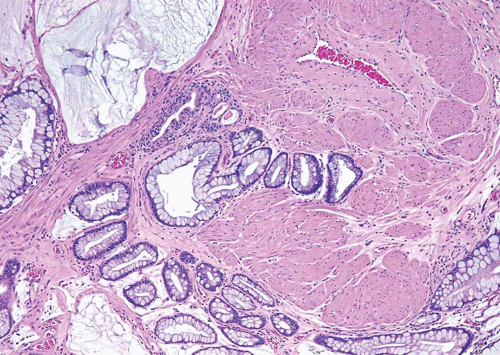

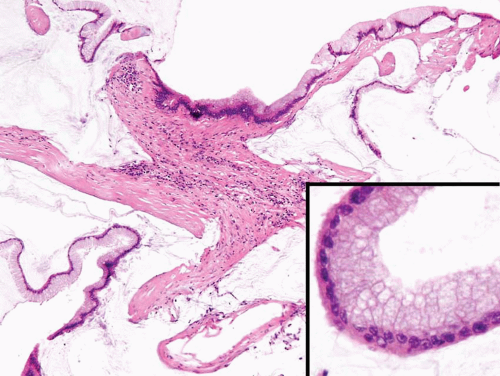

In some cases, the epithelial lining of Brunn nests and cystitis cystica undergo glandular metaplasia, giving rise to what is called cystitis glandularis (1, 2). The cells become cuboidal or columnar and mucin secreting; taking on the appearance of intestinal-type goblet cells. This variant is called cystitis glandularis with intestinal metaplasia (colonic metaplasia) (Figs. 8.1, 8.2, 8.3 and 8.4) (efig 8.1-8.19). The change may be focal or may diffusely replace the lining urothelium; both presenting as flat or minimally elevated or otherwise distorted mucosa. Some cases of intestinal metaplasia may be associated with abundant mucin extravasation and may present as symptomatic mass lesions. Although there is overlap between some examples of colonic metaplasia and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma in some of the histological features (dissecting mucin, infiltration of muscularis propria, reactive atypia, and mitoses), the degree and extent of these findings differ in the two conditions (3, 4). In contrast to the extensive mucinous pools seen in some adenocarcinomas, florid colonic metaplasia has only focal areas of mucin extravasation and is devoid of neoplastic cells within mucin pools. Whereas adenocarcinomas typically show extensive and deep muscularis propria invasion, colonic metaplasia is usually confined to the lamina propria, and muscularis propria involvement if present is typically limited and superficial (Fig. 8.5). Although rare adenocarcinomas may show bland cytology, most will have areas of the tumor with overt cytological atypia. The atypia seen in colonic metaplasia is typically negligible and mitoses, although frequent in adenocarcinoma, are found only rarely in colonic metaplasia. The cells lining the colonic-type glands are cytologically bland while those seen in carcinoma are more akin to what is seen in intramucosal carcinoma of the colon. Other cases of adenocarcinoma that are less differentiated show signet cells and necrosis, which are not found in colonic metaplasia. Long-term follow-up of cases of colonic metaplasia has confirmed a benign behavior (5). Exceptionally isolated glands of colonic metaplasia may show moderate-severe dysplasia, in an analogous fashion to those seen in a colonic adenoma; the significance of this finding is unknown although close follow-up is warranted (Fig. 8.6). In this setting, if the lesion is extensive on the initial transurethral resection, it may be prudent to suggest that the area be re-resected.

FIGURE 8.3 Cystitis glandularis, intestinal type. Note non-intestinal type cystitis cystica and glandularis (bottom). |

Glandular metaplasia may also occur within the surface urothelium, usually as a response to chronic inflammation or irritation, such as in cases of bladder extrophy (6, 7). The epithelium is composed of tall columnar cells with mucin-secreting goblet cells, strikingly similar to benign colonic or small intestinal epithelium in which one might identify even paneth cells.

FIGURE 8.5 Cystitis glandularis, intestinal type with extracellular mucinous pools dissecting muscularis propria. |

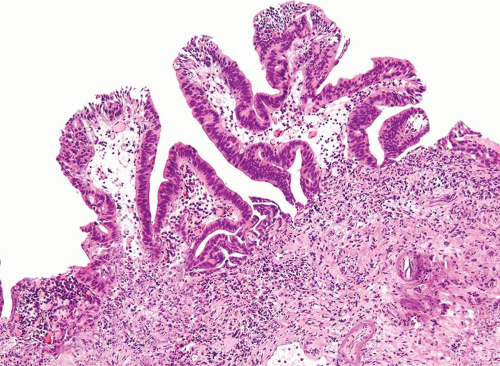

VILLOUS ADENOMA

The way to conceptualize glandular lesions occurring in the bladder and urethra is that they are analogous to glandular lesions seen in the intestinal tract, both in terms of lesion type and morphology. The full spectrum of lesions may be seen in the bladder and urethra, including villous adenoma, villous adenoma with in situ adenocarcinoma, villous adenoma with infiltrating adenocarcinoma, and infiltrating adenocarcinoma unassociated with villous adenoma. Villous adenomas and adenocarcinomas in the bladder occur in one of two general locations. They may arise within the urachus such that they are seen at the dome or anterior wall of the bladder, where they may present as a painful suprapubic mass. The glandular lesions can also arise in the bladder from a process of neo-metaplasia in which they may occur anywhere in the bladder, typically near the trigone.

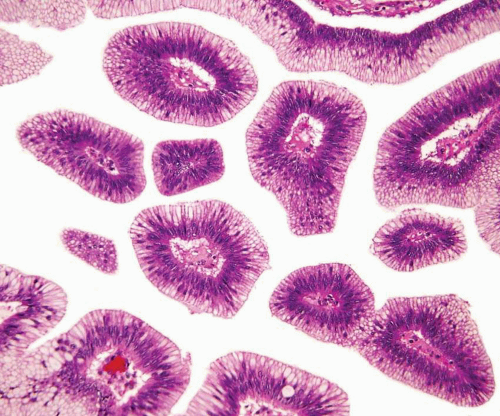

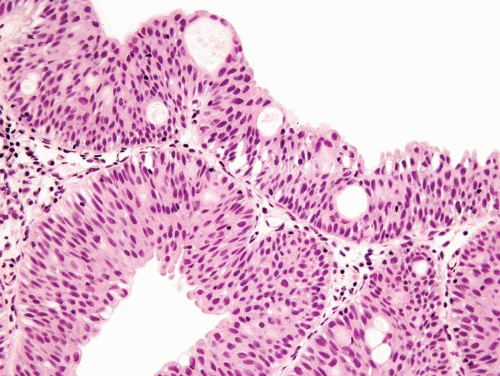

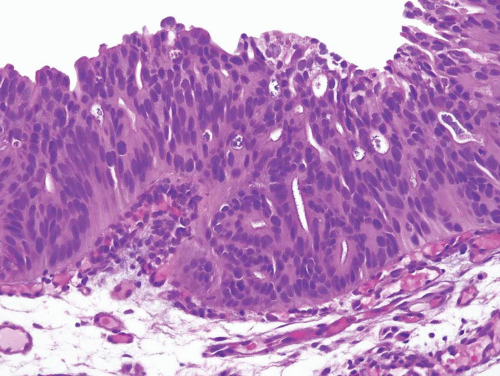

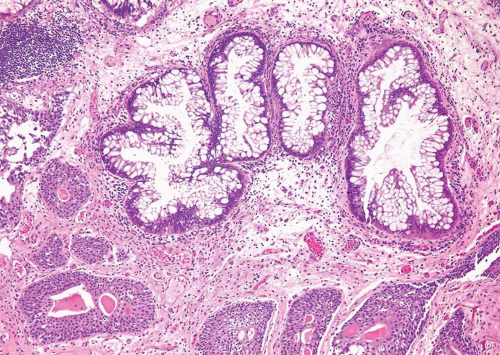

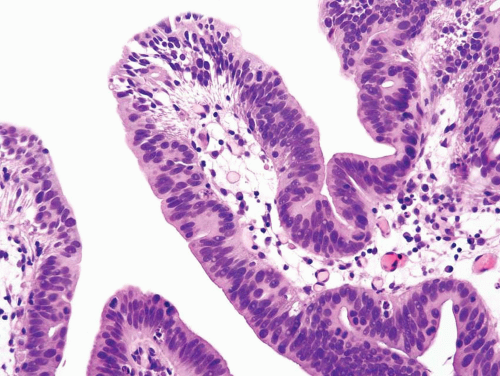

For both villous adenoma and adenocarcinoma of the bladder there is a male predominance. Patients with villous adenoma or adenocarcinoma may present with either nonspecific findings or occasionally present with mucosuria. If the lesion is pure villous adenoma with or without in situ adenocarcinoma and the lesion is entirely resected, then the prognosis is excellent (8, 9, 10, 11, 12). However, if the lesion has been only sub-totally removed, especially in the setting of coexistent in situ adenocarcinoma, the tumors have the potential to progress to infiltrating adenocarcinoma. As infiltrating adenocarcinoma is frequently present with villous adenoma, it necessitates thorough sampling of any lesion diagnosed by biopsy as villous adenoma. The diagnosis of villous adenoma should be reserved for cases in which the villous projections are lined by intestinal-type epithelium which exhibits typical adenomatous features (Figs. 8.7, 8.8, 8.9, 8.10 and 8.11) (efigs 8.20-8.36). Nuclei may be enlarged and multilayered with abundant apically located cytoplasm. Mitoses are unapparent or few and regular. Cytologic and architectural features of intramucosal carcinoma are absent. Caution is warranted in making a diagnosis of villous adenoma in a small biopsy sample as a surface villous histology may be seen in villous adenoma as well as villous adenoma associated with adenocarcinoma in which the latter is not sampled. Colonic/rectal adenocarcinomas can invade the bladder, mimicking a primary villous adenoma of the bladder, especially on limited biopsy material. Therefore, it is prudent to include a comment in the pathology report that while the lesion is probably a primary villous adenoma of the bladder, spread from an intestinal neoplasm should be clinically excluded.

In addition to in situ or invasive adenocarcinoma, urinary tract villous adenomas have been found in association with squamous cell carcinoma, flat in situ urothelial carcinoma, noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma, infiltrating urothelial carcinoma, and sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Associated urothelial carcinoma elements are not always discrete from villous adenomas, but often merge imperceptibly with them. These findings indicate that glandular lesions of the urothelium, whether benign or malignant, arise from a process of metaplasia/neo-metaplasia, and are a manifestation of the morphologic plasticity of the urothelium.

NONINVASIVE UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA WITH GLANDULAR DIFFERENTIATION (IN SITU ADENOCARCINOMA)

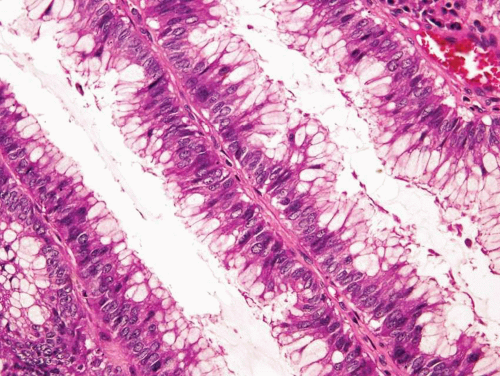

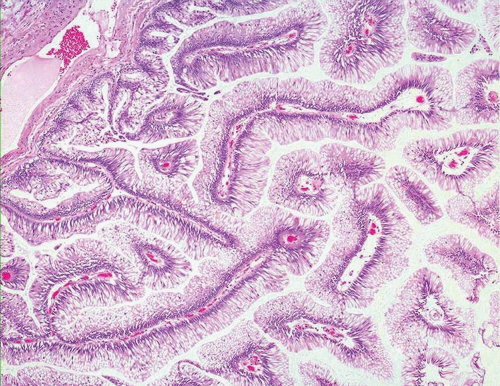

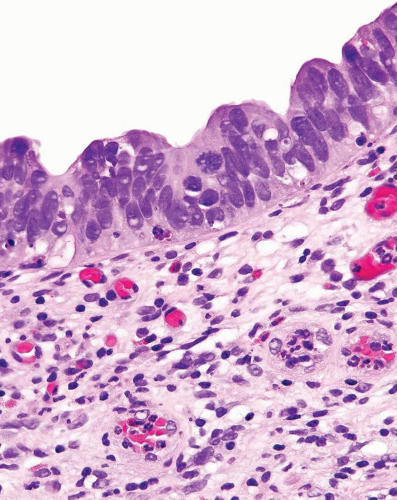

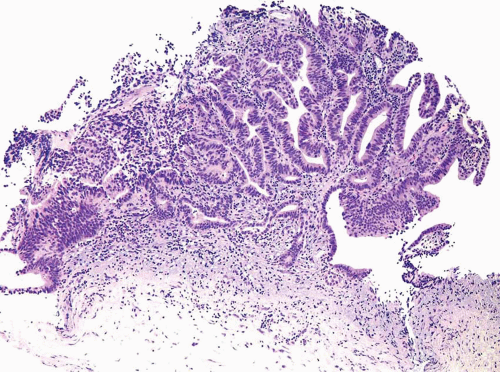

Noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinomas may have gland-like lumina, a common finding that should not be confused with adenocarcinoma (Figs. 8.12, 8.13). In other cases the noninvasive component, flat or papillary, may exhibit unequivocal glandular features (Figs. 8.14, 8.15, 8.16, 8.17 and 8.18) (efigs 8.37-8.54). Chan and Epstein described a series of 19 cases of noninvasive urothelial carcinomas with glandular differentiation (referred to as

“in situ adenocarcinoma”) of the bladder unaccompanied by infiltrating adenocarcinoma (13). Noninvasive urothelial carcinomas with glandular differentiation had a high incidence of association with carcinoma in situ (CIS) and specific subtypes of prognostically poor invasive carcinomas, such as small cell and micropapillary urothelial carcinoma. In a more recent, larger study from the same group, the noninvasive glandular component consisted of one or more patterns, including papillary, glandular, cribriform, and flat. Half of the cases were associated with “usual” urothelial CIS or high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. Of those cases that subsequently progressed to invasion, none did so as adenocarcinoma but rather as small cell carcinoma or poorly differentiated urothelial carcinoma (14). These data confirm that this disease is a morphologic variant of urothelial CIS and that divergent differentiation in urothelial carcinoma, whether invasive or not, is usually associated with aggressive clinical behavior.

“in situ adenocarcinoma”) of the bladder unaccompanied by infiltrating adenocarcinoma (13). Noninvasive urothelial carcinomas with glandular differentiation had a high incidence of association with carcinoma in situ (CIS) and specific subtypes of prognostically poor invasive carcinomas, such as small cell and micropapillary urothelial carcinoma. In a more recent, larger study from the same group, the noninvasive glandular component consisted of one or more patterns, including papillary, glandular, cribriform, and flat. Half of the cases were associated with “usual” urothelial CIS or high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. Of those cases that subsequently progressed to invasion, none did so as adenocarcinoma but rather as small cell carcinoma or poorly differentiated urothelial carcinoma (14). These data confirm that this disease is a morphologic variant of urothelial CIS and that divergent differentiation in urothelial carcinoma, whether invasive or not, is usually associated with aggressive clinical behavior.

FIGURE 8.13 Noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma with gland-like lumina (higher magnification (right)). |

FIGURE 8.15 Noninvasive urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation, papillary pattern composed of simple and branching fronds. |

FIGURE 8.16 Higher magnification of Figure 8.15 shows glandular differentiation with columnar nuclei and apical cytoplasm. The nuclei still retain some of the features of CIS cells (i.e., hyperchromatic enlarged cells without prominent nucleoli). |

FIGURE 8.17 Noninvasive urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation, complex papillary pattern. |

INFILTRATING ADENOCARCINOMA

Primary pure adenocarcinomas of the bladder are rare, representing no more than 2.5% of all malignant vesical neoplasms. By definition, the tumor should be composed entirely, or virtually entirely of glandular elements. As with other variants, they arise through a process of divergent differentiation in urothelial carcinoma (15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21). Adenocarcinomas constitute up to 90% of carcinomas associated with bladder extrophy. The tumor is also more frequently encountered in a setting of schistosomiasis. Shaaban et al. (22) and El-Mekresh et al. (23) reported a series of 93 and 185 cases, respectively, of vesical adenocarcinoma arising in this setting. Adenocarcinomas can arise anywhere on the bladder surface although a large percentage originates from the trigone and posterior wall. A major clinical difference as compared to usual urothelial carcinomas is that two thirds of adenocarcinomas are single discrete lesions while “usual” urothelial carcinoma tend to be multifocal (24, 25). Grossly, the tumors can be papillary, nodular or flat, and ulcerated. Microscopically, the tumor is most often composed of colonic-type glandular epithelium (enteric morphology) and often contains abundant extracellular mucin (Figs. 8.19, 8.20 and 8.21) (efigs 8.55-8.68). However, some tumors are highly cellular, cytologically less well-differentiated and do not contain extracellular mucin. We have seen rare examples with hepatoid or even yolk sac differentiation, the latter associated with serum elevation of alfa fetoprotein. Regardless of the histologic pattern, cystitis cystica and glandularis or surface glandular metaplasia is commonly present in the adjacent benign urothelium. Rarely, they may be associated with villous adenoma of the bladder. Most adenocarcinomas have infiltrated deeply at the time of initial diagnosis and are associated with a poor prognosis.

Recent data suggest that, in its pure form, adenocarcinoma arising in the bladder has a worse prognosis than usual urothelial carcinoma even after adjusting for pathologic stage, lymph node status and the presence of lymphovascular invasion (26). Whether this finding is due to the resistance of adenocarcinoma differentiation to systemic therapies directed at usual urothelial carcinoma remains to be proven.

Recent data suggest that, in its pure form, adenocarcinoma arising in the bladder has a worse prognosis than usual urothelial carcinoma even after adjusting for pathologic stage, lymph node status and the presence of lymphovascular invasion (26). Whether this finding is due to the resistance of adenocarcinoma differentiation to systemic therapies directed at usual urothelial carcinoma remains to be proven.

In the differential diagnosis one must first consider the possibility of secondary adenocarcinoma involving the bladder, either by metastasis or direct invasion. Theoretically, it should be important to identify

in situ carcinoma, although this is rarely possible on TUR specimens due to ulceration of the overlying urothelium or to incomplete sampling. Furthermore, secondary tumors such as colonic adenocarcinoma with invasion of the bladder wall may colonize the urothelium, mimicking in situ disease. Tumors that directly invade the bladder and mimic primary vesical adenocarcinoma include those arising in the rectum, prostate, appendix and endometrium (24, 25, 27). The only unequivocal way to establish such a tumor as a primary vesical neoplasm is to see a transition to usual urothelial carcinoma. For this reason, we have routinely added the following disclaimer to our pathology report of the biopsy specimen… “we would accept as primary at this site if a metastasis or direct extension from an adjacent organ can be ruled out clinically.” The treating clinician is in the best position to evaluate the patient and consider other primary sites.

in situ carcinoma, although this is rarely possible on TUR specimens due to ulceration of the overlying urothelium or to incomplete sampling. Furthermore, secondary tumors such as colonic adenocarcinoma with invasion of the bladder wall may colonize the urothelium, mimicking in situ disease. Tumors that directly invade the bladder and mimic primary vesical adenocarcinoma include those arising in the rectum, prostate, appendix and endometrium (24, 25, 27). The only unequivocal way to establish such a tumor as a primary vesical neoplasm is to see a transition to usual urothelial carcinoma. For this reason, we have routinely added the following disclaimer to our pathology report of the biopsy specimen… “we would accept as primary at this site if a metastasis or direct extension from an adjacent organ can be ruled out clinically.” The treating clinician is in the best position to evaluate the patient and consider other primary sites.

FIGURE 8.21 Infiltrating adenocarcinoma, colloid type, with abundant extracellular mucinous secretions. Note relatively bland cytology (inset). |

Urothelial carcinomas may also be associated with abundant myxoid stroma, mimicking a primary or secondary adenocarcinoma (28). In urothelial carcinoma with myxoid stroma, the infiltrating component has urothelial rather than glandular features and the tumor cells consist of cords and nests of cells embedded in a myxoid stroma which is positive for mucicarmine, periodic acid-Schiff, and alcian blue with and without hyaluronidase (Figs. 8.22, 8.23). Infiltrating urothelial carcinoma with gland-like lumina should also be distinguished from adenocarcinoma (Fig. 8.24).

Immunohistochemistry may aid in establishing the primary site (29). Urothelial carcinoma of the usual type is likely to express CK7 and CK20 as well as 34βE12, p63 (clone 4A4), and thrombomodulin. Carcinomas with glandular differentiation are quite likely to lose expression of some or all of these markers with the exception of CK20. In addition, they are likely

to neo-express CDX-2 and β-catenin, the latter in a cytoplasmic rather than a nuclear distribution. In contrast, colonic adenocarcinoma will usually express CK20 diffusely but not CK7. β-Catenin is usually expressed in a nuclear distribution and thrombomodulin is universally negative. Immunohistochemistry for CEA and villin are not useful in solving this differential diagnosis.

to neo-express CDX-2 and β-catenin, the latter in a cytoplasmic rather than a nuclear distribution. In contrast, colonic adenocarcinoma will usually express CK20 diffusely but not CK7. β-Catenin is usually expressed in a nuclear distribution and thrombomodulin is universally negative. Immunohistochemistry for CEA and villin are not useful in solving this differential diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree