pressure is reduced, and compounding this is ineffective peristalsis with delayed esophageal clearance.3 Delayed gastric emptying (see below) contributes to reflux by increasing the volume of reflux, which is poorly cleared as a result of the esophageal motor disorder.14, 15 Thus erosive esophagitis may be severe and associated with stricture formation.12, 16 In the end stages, the esophagus may appear dilated, with a stricture at the lower esophageal sphincter region and little or no peristalsis in the body of the esophagus. Patients are additionally predisposed to candidal esophagitis due to a combination of poor esophageal emptying, frequent use of immunosuppressive agents, and acid suppression. Dysmotility also predisposes to “pill esophagitis” due to increased mucosal contact with the pill. Bisphosphonates, NSAIDs, quini-dine, and potassium chloride have been implicated in these patients. Appropriate counseling is important to prevent this unpleasant complication.3, 12 Any putative increased incidence of squamous carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the esophagus in scleroderma is probably due to the associated gastroesophageal reflux disease rather than due to any intrinsic risk conferred by the connective tissue disease itself.3, 17

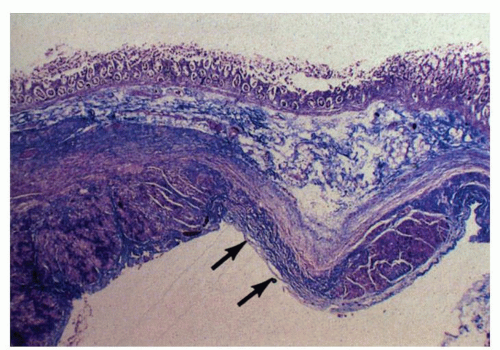

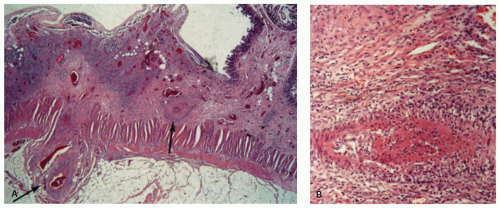

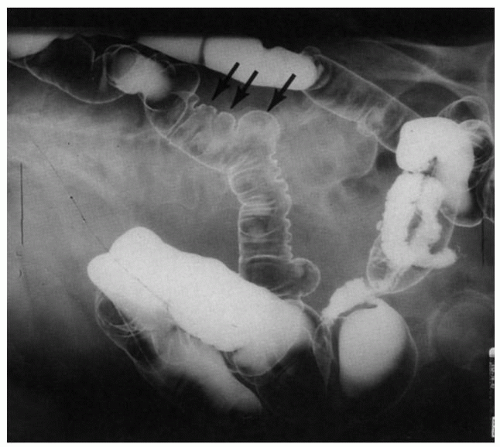

Figure 8-1. Scleroderma of the gastrointestinal tract. Barium enema examination to show wide-mouthed diverticula (arrows). (Courtesy of Dr M Weiner UCLA.) |

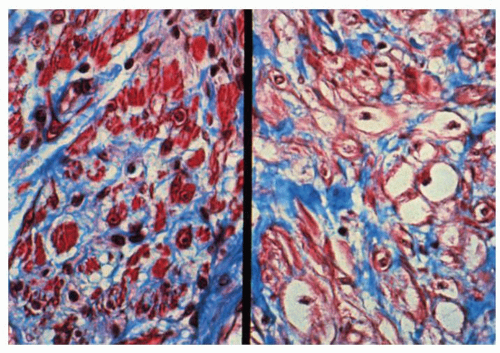

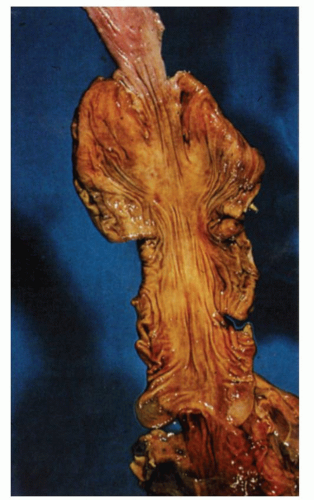

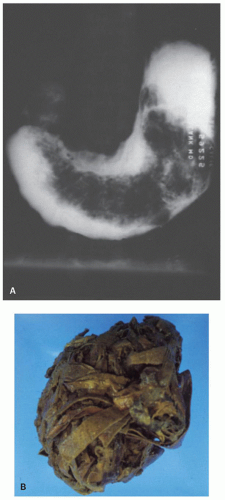

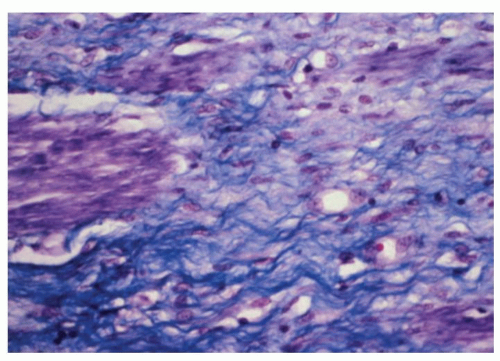

commonly, the former affects the circular muscle coat. Fibrosis accompanies the muscle atrophy but appears to be the replacement of the atrophied muscle rather than active fibroblastic proliferation. Collagen deposition in the submucosa and subserosa is very variable. Muscle atrophy results in atony and dilatation and may produce flaccid, wide-mouthed diverticula (Fig. 8-1), and, less commonly, mega-duodenum or megacolon.33 Diverticula are better appreciated radiologically when distended with barium than when collapsed at autopsy or in resection specimens. They are not generally complicated by diverticulitis because their wide necks are less prone to obstruction.10 The muscle changes of scleroderma most closely resemble those of idiopathic familial and sporadic visceral myopathy. The major difference between the two entities consists of muscle atrophy with fibrous replacement in scleroderma compared to vacuolar degeneration resulting in clear spaces surrounded by collagen in visceral myopathy (Fig. 8-4) (see Chapter 7 for further details). Mucosal changes in scleroderma are secondary to motor dysfunction. In the esophagus, severe erosive esophagitis and superinfection with Candida may be seen.34 Associated stricture formation is common in scleroderma, and it may be made more intractable by submucosal collagen formation. In the stomach, submucosal and mural fibrosis may result in a lack of distensibility with consequent early satiety. Occasionally, severe atrophy of the gastric wall musculature may result in a small, shrunken stomach (Fig. 8-5). Collagen encapsulation of Brunner’s glands has been reported in duodenal biopsies,35, 36, 37 but this is not a consistent finding38, 39 and is often present in duodenal biopsies in general.

Figure 8-3. Detail of Figure 8-2 to show atrophy of muscularis propria. Note the replacement of muscle fibers (stained purple) by collagenous fibrous tissue (trichrome stain). |

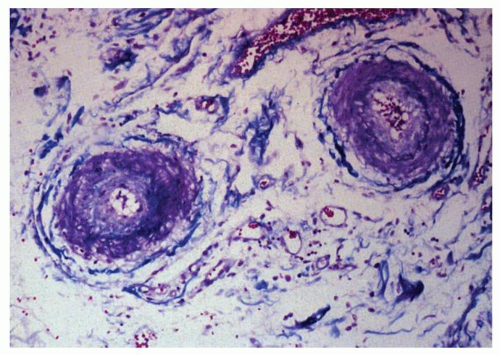

Sometimes the associated vascular abnormality may be masked at endoscopy by an area of subepithelial hemorrhage. If vasculitic lesions have progressed, then the changes may be those of erosions or ulcerations. Lesions vary from small, ischemic ulcers to transmural infarction and perforation, depending on the size and number of vessels involved.28 Patients are also prone to pneumatosis intestinalis. Histologically, the small vessels of the bowel frequently show a proliferative endarteritis with endothelial swelling, intimal proliferation,10 and a peculiar mucinous change of the media 40 (Fig. 8-6). In addition, there may be a vasculitis, which can affect the mesenteric arteries at any level.

to decreased production of saliva, upper esophageal webs, parasympathetic dysfunction, and esophageal dysmotility,41, 85, 86, 87 although the role of the latter has been questioned.85, 86 Atrophic gastritis and duodenal ulcers have been described,41, 87 but whether this is a true association and not ulcers secondary to medications and long-standing Helicobacter is unclear. Patients with Sjögren’s may also be at increased risk for the development of lymphomas including MALT lymphomas of the stomach,87, 88, 89 and this should be borne in mind when evaluating endoscopic biopsies from such patients.

intrinsic gut lesions occur in this disorder. Putative associations with gastritis were claimed on the basis of studies with blind suction biopsies,104 and claims of mild small bowel lesions need confirmation because the illustrations in one published report are not convincing.105 A small study in autoimmune thyroid disease suggested that there were more lymphoid follicles present in Helicobacter pylori-positive patients than in controls with H. pylori infection. The significance of this is unclear.106 An ileus-like picture with vomiting has been reported in a case of “thyroid storm.”107 Uncommonly dysphagia occurs in thyrotoxicosis and may be secondary to direct compression from a goiter, neurohumoral dysregulation, or a generalized myopathy including striated muscles of the pharynx and smooth muscle of the esophagus.101, 108, 109 Histologic changes in the esophagus have not been reported.

the diarrhea remain to be elucidated but impaired enteropancreatic peptide secretion following caloric stimulus and increased epithelial permeability due to cytoskeletal alterations have been suggested to play a role.129

susceptible to infections in the gut, especially esophageal candidiasis,148 and in ketoacidosis there may be severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding from gastric erosions, presumably of the stress type. There is an increased incidence of atrophic gastritis with pernicious anemia and celiac sprue among type 1 diabetics. These cases are associated with significant titers of circulating parietal cell antibodies and often thyroid antibodies.149, 150, 151, 152 The prevalence of autoimmune gastritis in type 1 diabetics is three- to fivefold higher than that of the general population. Celiac disease is reported in up to 5% to 10% of patients with type 1 diabetes152, 153, 154 compared to 0.55% to 1% in the general population in Europe and North America. In most cases the diagnosis of diabetes precedes that of celiac disease. One study found the prevalence of symptomatic celiac disease at diagnosis to be 0.7%, but this increased to 10% after 5 years of annual screening.154 Many centers advocate routine annual screening for celiac disease in type 1 diabetics with a minimum of 2 years suggested.154 (Celiac disease is further discussed in Chapter 20.)

also result from diffuse hyperplasia of the islets162 and occasionally from ganglioneuromas or ganglioneuro-blastomas, which secrete vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP).167, 168 The syndrome is characterized by profuse watery secretory diarrhea (i.e., resistant to fasting), with hypersecretion of water and electrolytes, resulting in severe dehydration, hypokalemia, and metabolic acidosis. VIPomas may secrete other products such as gastrin, serotonin, gastrin inhibitory polypeptide, and somatostatin, which may contribute to the diarrhea.166 No morphologic abnormalities have been described in the gastrointestinal tract.

(50% of patients with Zollinger-Ellison have MEN I),206 or diarrhea due to the carcinoid syndrome, VIPoma, or medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. Hirschsprung’s disease is occasionally seen in patients with MEN IIa.208

Table 8-1 Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN) Syndromes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

of deaths in patients on maintenance dialysis.220, 225 Cardiovascular complications of chronic renal failure, such as hypertension and arteriosclerosis, may predispose to intestinal ischemia.

Table 8-2 Interrelationship of Gastrointestinal and Renal Diseases | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree