- Primary gastrointestinal (GI) tract lymphoma is relatively rare and encompasses many subtypes. In contrast, the GI tract is the most common extranodal site to be involved with advanced lymphoma. Correct histological diagnosis is essential for prognostic evaluation and to guide optimum management and follow-up.

- Initial staging investigations of lymphoma include computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, abdomen, pelvis; bone marrow biopsy; full blood count and film; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH); uric acid; assessment of organ function; and positron emission tomography (PET) scan plus endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) where indicated.

- GI tract lymphoma is generally treated with chemotherapy regimens used for nodal counterparts of identical histological subtype. The only exception is localized extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) in the stomach, which should initially be treated with Helicobacter pylori eradication. Radiotherapy can be utilized in localized disease. Surgery plays a very limited role in the treatment of lymphoma, and decisions regarding its use in individual cases should be agreed by a multidisciplinary team.

The UK Lymphoma Association

UK Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research

The American National Cancer Institute Web site (Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma)

- Accurate diagnosis can be difficult to obtain and may require repeat procedures in order to obtain adequate tissue specimens.

- Certainty of the diagnosis is vital due to the prominent role of chemotherapy or radiotherapy rather than surgery as a first-line treatment strategy in localized disease.

- Staging investigations differ considerably from other malignancies of the GI tract; therefore, early referral to a lymphoma specialist is essential.

- Routine follow-up varies depending on lymphoma subtype. Specific procedural requirements for endoscopy must be relayed to the endoscopist, particularly with MALT lymphoma (gastric mapping) to ensure adequate assessment of disease.

Introduction

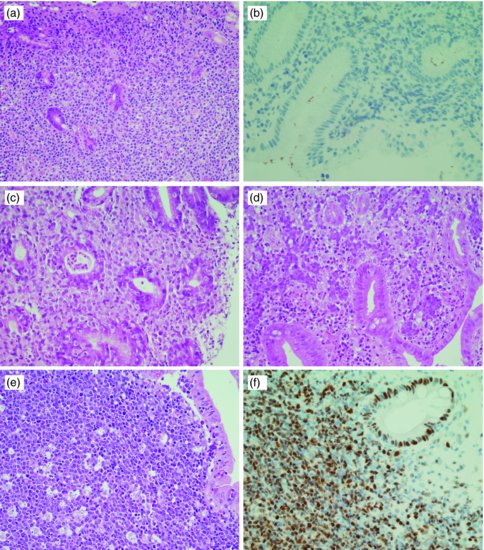

The term “gastrointestinal (GI) lymphoma” is generally reserved for primary extranodal lymphomas that arise in the GI tract; however, involvement of the GI tract by lymphoma has been described with all histological subtypes. GI lymphoma is the most common form of primary extranodal lymphoma, accounting for 30–40% of cases. The most common site of disease is the stomach (60–70% of cases) followed by small bowel, ileocecal region, duodenum, colon, and rectum.1,2 The most common histologies are diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). Other GI-specific lymphomas, although rare, include enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) and immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (IPSID). Less common extranodal lymphomas of the GI tract are mantle cell lymphoma (MCL); follicular lymphoma (FL); peripheral T-cell lymphoma, which present far more commonly as nodal disease; and Burkitt lymphoma (BL) (Figure 10.1, Tables 10.1 and 10.2).

Figure 10.1 Histological images of primary GI lymphomas: (a) MALT lymphoma; (b) MALT lymphoma-Helicobacter pylori immunostaining; (c) EATL Type I duodenum; (d) DLBCL colon; (e) Burkitt lymphoma colon; (f) MCL colon-CyclinD1 immunostaining.

Table 10.1 Common primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

| B cell |

| Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) |

| Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma—not otherwise specified |

| Mantle cell lymphoma |

| Follicular lymphoma |

| Burkitt lymphoma |

| T cell |

| Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma |

Table 10.2 Common immunophenotypic features of common GI lymphomas.

A wide geographical variability in incidence exists, with the highest rates in the Middle East. Of interest, the most common disease site in Middle Eastern countries is the small intestine, rather than the stomach.3 A 13-fold higher incidence of gastric MALT lymphoma in north-east Italy compared with Britain has also been described.4 This variability probably arises due to the different prevalence of etiological factors such as Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection (associated with MALT lymphoma) in north-east Italy.

Presentation is often with nonspecific symptoms that develop at a rate determined by the aggressiveness of the underlying lymphoma pathology. Dyspepsia, abdominal pain and/or bloating, change in bowel habit, hemorrhage, and, rarely, perforation or obstruction are seen. Classical B symptoms are less common than nodal lymphoma, with weight loss usually secondary to the abdominal symptoms rather than as a direct result of the lymphoma. Physical examination uncommonly yields specific findings. However, a palpable abdominal mass, peripheral lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, and features of autoimmune or immunodeficiency disorders should be excluded.

Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

Epidemiology

MALT lymphoma is an indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) first described as a separate entity in 1983 by Isaacson and Wright.5 Accounting for 8% of all NHL, approximately one-third of MALT lymphomas originate in the stomach.6 MALT lymphoma arises from marginal zone B cells that have undergone postfollicular differentiation following chronic antigenic stimulation secondary to persistent infection or autoimmune disease. In the stomach, it is strongly associated with H. pylori infection with 90–95% of patients with gastric MALT lymphoma showing evidence of concurrent or previous infection,7,8 compared with 50% of the global population.9

Other infections that have been linked to MALT lymphoma in nongastric locations include Chlamydia psittaci (ocular adnexa), Borrelia burgdorferi (skin), and Campylobacter jejuni (small bowel). An association with autoimmune diseases is also described including Sjögren’s syndrome (salivary gland MALT lymphoma), Hashimoto’s autoimmune thyroiditis (thyroid MALT lymphoma), and polymyalgia rheumatica. Uncertainty remains as to whether lymphoma outcomes differ in this population.10,11 No inherited component has been identified.

The median age at presentation is 61 years12 and prognosis is generally considered good. Poor prognostic features include non-GI or distant nodal involvement, poor WHO performance status, bulky tumor, high beta-2 microglobulin level, high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), low serum albumin, and anemia.13 Five-year survival ranges from 80% to 95%, despite progression-free survival (PFS) being comparably short in those with advanced stage or poor prognostic features.13–16

Diagnosis and staging

MALT lymphoma is often multifocal disease in the organ of origin and is frequently macroscopically indistinguishable from other disease processes in the GI tract.17 Endoscopy is key to diagnosing MALT lymphoma, with multiple biopsies of the visible lesions required, as well as samples of macroscopically normal tissue, termed “gastric mapping.”

Histologically, there is expansion of the marginal zone compartment with development of sheets of neoplastic small lymphoid cells (Figure 10.1a). The morphology of the neoplastic cells is variable with small mature lymphocytes, cells resembling centrocytes (centrocyte-like cells), or marginal zone/monocytoid B cells. Plasmacytoid or plasmacytic differentiation is frequent. Lymphoid follicles are ubiquitous to MALT lymphoma but may be indistinct as they are often overrun or colonized by the neoplastic cells. Large transformed B cells are present scattered among the small cell population. If these large cells are present in clusters or sheets, a diagnosis of associated large B-cell lymphoma should be considered. A characteristic feature of MALT lymphoma is the presence of neoplastic cells within epithelial structures with associated destruction of the glandular architecture to form lymphoepithelial lesions.

MALT lymphoma may be difficult to distinguish from reactive infiltrates, and in some cases, multiple endoscopies are required before a confident diagnosis is reached. The Wotherspoon score, which grades the presence of histological features associated with MALT lymphoma, is useful in expressing confidence in diagnosis at presentation (Table 10.3).18

Table 10.3 Histological scores for response assessment in gastric MALT lymphoma.

| Wotherspoon histological score for diagnosis18 | ||

| Grade | Description | Histological features |

| 0 | Normal | Scattered plasma cells in LP. No lymphoid follicles |

| 1 | Chronic active gastritis | Small clusters of lymphocytes in lamina propria. No lymphoid follicles. No LELs |

| 2 | Chronic active gastritis with florid lymphoid follicle formation | Prominent lymphoid follicles with surrounding mantle zone and plasma cells. No LELs |

| 3 | Suspicious lymphoid infiltrate in LP, probably reactive | Lymphoid follicles surrounded by small lymphocytes that infiltrate diffusely in LP and occasionally into epithelium |

| 4 | Suspicious lymphoid infiltrate in LP, probably lymphoma | Lymphoid follicles surrounded by CCL cells that infiltrate diffusely in LP and into epithelium in small groups |

| 5 | Low-grade B-cell lymphoma of MALT | Presence of dense diffuse infiltrate of CCL cells in LP with prominent LELs |

| GELA grading system for posttreatment evaluation83 | ||

| GELA category | Histology | |

| CR (complete histological response) | Absent or scattered plasma cells and small lymphoid cells in the LP. No LELs. Normal or empty LP and/or fibrosis | |

| pMRD (probable minimal residual disease) | Aggregates of lymphoid cells or lymphoid nodules in the LP/muscularis mucosa and/or submucosa. No LELs. Empty LP and/or fibrosis | |

| rRD (responding residual disease) | Dense, diffuse, or nodular extending around glands in the LP Focal or no LELs focal empty LP and/or fibrosis | |

| NC (no change) | Dense, diffuse, or nodular LELs present (may be absent). No changes | |

| CCL, centrocyte like; LEL, lymphoepithelial lesions; LP, lamina propria. | ||

Immunohistochemistry can be used to help distinguish MALT lymphoma from other small B-cell NHLs. B-cell-associated antigens such as CD19, CD20, CD22, and CD79a are usually expressed. In contrast to small lymphocytic lymphoma and MCL, staining for CD5 is usually negative, and these lymphomas can be further distinguished with CD23 (positive in small lymphocytic lymphoma) and CyclinD1 (positive in MCL).

Immunoglobulin genes are rearranged and B-cell monoclonality is present in almost all cases, and PCR analysis may be useful where diagnosis remains ambiguous although caution is advised as a proportion (probably up to 3%) of gastritis cases may give a clonal pattern. Cytogenetic translocations seen in MALT lymphoma include translocation t(11;18)(q21;q21), t(14;18)(q32;q21), and occasionally t(1;14)(p22;q32). Each of these has a final common pathway resulting in aberrant activation of NFκB. Trisomies 3 and 18 have been described. When present, t(11;18) is usually the sole cytogenetic abnormality found and this translocation is almost never seen in cases that transform to more aggressive large cell lymphoma.21 Testing for t(11;18) is important, as evidence suggests that it is associated with more advanced, invasive tumors and with lymphomas that are less likely to respond to H. pylori eradication.22 The t(11;18) is present in 25–40% of gastric cases; however, higher frequencies are seen in MALT lymphoma of the lung, while it is rare in MALT lymphomas of the thyroid, ocular adnexa, and skin.23,24

Due to the causal relationship between H. pylori infection and MALT lymphoma, identification of the infection is mandatory. Histological examination of GI biopsies yields a sensitivity of 95% with five biopsies,25 but these should be from sites uninvolved by lymphoma and the identification of the organism may be compromised by areas of extensive intestinal metaplasia (Figure 10.1b). As proton-pump inhibition can suppress infection, any treatment with this class of drug should be ceased 2 weeks prior to biopsy retrieval. Serology should be performed if histology is negative, to detect suppressed or recently treated infections.26,27

The Ann Arbor staging system28 (Table 10.4), originally designed for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, has been adapted for NHL to assist in determining prognosis and management. However, its prognostic value is significantly limited in MALT lymphoma with GI tract localization at presentation, as depth of gastric wall invasion is an important predictive factor for response to H. pylori eradication therapy. Musshoff originally suggested a modified Ann Arbor system,29 which was then further modified in 1994 to the Lugano system,19 which is still used today. The “TNMB” or Paris staging system20 has been proposed to more accurately incorporate tumor depth and local spread; however, it is variably used in clinical practice (Table 10.5).

Table 10.4 Ann Arbor staging system for lymphoma.30

| Stage | Extent of tumour spread |

| I | Single anatomical lymph node region (I) Or single extralymphatic site (IE)a |

| II | ≥2 lymph node regions or lymphatic structures (II) and/or an extralymphatic site (IIE) on the same side of the diaphragm |

| III | Lymph node regions above and below the diaphragm (III) and/or an extralymphatic site (IIIE) above and below the diaphragm |

| IV | Widespread involvement of ≥1 extralymphatic organs or tissues, +/− lymphatic involvement. |

| Notes: Each stage is further divided according to absence (A) or presence (B) of “B” symptoms, which include fever (>38°C), night sweats, or weight loss >10% of total body weight <6 months prior to diagnosis, which are attributed to the lymphoma. For example, a patient with stage IA lymphoma has no “B” symptoms, whereas Stage IIB has at least one “B” symptom present. The presence of splenic involvement is denoted by the label “S” after the stage (e.g., Stage IIIS or Stage IIIES if there is both splenic and extranodal involvement). aThe label “E” generally refers to extranodal disease that can be encompassed within a single radiation field. | |

Table 10.5 Lugano19 and Paris20 staging systems for gastrointestinal lymphomas.

| Lugano staging | Paris staging | Extent of tumor spread |

| Stage I I1 I2 | T1–3 N0 M0 T1 N0 M0 T2-T3 N0 M0 | Tumor confined to GI tract (Single primary site or multiple noncontiguous lesions) Infiltration limited to mucosa and/or submucosa Tumor extends into muscularis propria and/or subserosa and/or serosa |

| Stage II II1 II2 | T1–3 N0–2 M0 T1–3 N1 M0 T1–3 N2 M0 | Tumor extending into abdomen from primary GI site (nodal involvement) Local Perigastric nodes in gastric lymphoma Mesenteric in small and large bowel lymphoma Distant Mesenteric in gastric lymphoma Para-aortic, paracaval, pelvic, inguinal |

| Stage IIE | T4N0–2M0 | Penetration of serosa with involvement of adjacent organs/tissues (Enumerate actual site of involvement, e.g., IIE(pancreas), IIE (large intestine)) Where there is both nodal involvement and penetration into adjacent organs, stage should be denoted using both subscript and E, e.g., II1E(pancreas) |

| Stage IV | T1–4 N3M0 T1–4 N0–3 M1–2 B1 | GI tract lesion with supradiaphragmatic or extra-abdominal nodal involvement Disseminated extranodal involvement (M1 = noncontiguous separate site in GI tract, M2 = noncontiguous other organs) Bone marrow involved |

As MALT lymphoma has a predisposition to preferentially spread to other extranodal sites, staging investigations must include clinical examination of the oropharynx, thyroid, and Waldeyer’s ring. Referral for ophthalmologic examination and imaging of the salivary glands should be considered to ascertain involvement of other extranodal sites. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, as well as bone marrow aspirate and trephine examining for distant spread; endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for gastric MALT to assess depth and local nodal involvement; and hematological and biochemical parameters including full blood count, LDH, and beta-2 microglobulin should all be performed. Positron emission tomography (PET) is not recommended routinely as MALT lymphoma is often PET negative.

Investigation for associated autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren’s syndrome and autoimmune thyroiditis should also be considered.

Treatment

Historically, surgical treatment of localized disease was adopted with high cure rates. Distal partial gastrectomy was frequently associated with stump recurrence after a disease-free interval and total gastrectomy resulted in significant long-term morbidity. With the advent of stomach conserving therapies with similar outcomes, the role of surgery is restricted to the treatment of rare complications such as perforation or bleeding that cannot be controlled endoscopically.30

Following the recognition of the association of gastric MALT lymphoma with H. pylori infection, it was established that early-stage gastric disease could be cured by H. pylori eradication, which is now the mainstay of therapy. Fifty to 95% of cases achieve complete response (CR) with H. pylori treatment.18,31 H. pylori eradication therapy consists of proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) plus clarithromycin-based triple therapy with amoxicillin or metronidazole for 14 days. Increasing clarithromycin-resistant strains has led to the recommendation that this drug is avoided in areas where resistant strains are prevalent. In these areas, and when second-line therapy is required, quadruple therapy with PPI, colloidal bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole is recommended and this is effective even in areas with high prevalence of metronidazole-resistant strains.

A urea breath test should be performed approximately 2 months after treatment and at least 2 weeks after withdrawal of PPI therapy to confirm eradication. The time to remission can be 12 months or longer in some cases. The rates of relapse are reasonably high in some series (22% gastric, up to 48% systemic).32,33 It is recommended that patients be followed up closely with repeat endoscopy, gastric mapping biopsies, and EUS.

Due to the usually localized nature of this disease and the requirements of biopsy to diagnose a response, the standard response criteria for lymphoma34 based on radiological imaging results are difficult to apply. However, repeat CT imaging is recommended. Endoscopic evaluation of response is imperative in localized disease, with histological assessment of posteradication biopsies being crucial to the planning of further management. Assessment of sequential biopsies using the GELA grading system gives useful information in this regard with clear indication of the quality of response over time.31 Many patients will have residual lymphoid aggregates in the gastric mucosa following complete endoscopic resolution of the lesion, termed probable minimal residual disease in the GELA scheme. These frequently harbor occasional clonal B cells but are of no clinical significance, as long-term follow-up has shown that they usually remain unchanged or show regression over time. The presence of these small clonal populations in residual lymphoid aggregates mean molecular follow-up by PCR has no role in the clinical setting. In the absence of further evolution of disease, either histologically or macroscopically, no further intervention is required. In some patients, histologically detected relapse may develop. This may be associated with recrudescence of H. pylori in which case further eradication may result in further remission. In a proportion of cases, small histologically detected relapses have been shown to regress on subsequent biopsies without further therapy and hence a “watch and wait” policy may be adopted.

Overall 30–40% of patients will not respond to H. pylori eradication.8 The probability of response to H. pylori eradication appears to be related in part to the depth of mural invasion and to local nodal involvement, with the more invasive cases less likely to respond. Failure to respond the eradication therapy alone has also been shown to be related to the presence of t(11;18) with cases harboring the translocation unlikely to respond.

Extra-gastric MALT lymphomas have, in some cases, been shown to respond to antibiotic-related therapies. While this is unlikely to be due to H. pylori itself, it is possible that other microbial factors could be involved in the pathogenesis of the lymphomas at these sites with eradication of these organisms having a similar effect on the lymphoma.

For those requiring further management, there is no consensus on standard treatment. Published data are largely restricted to phase II trials and retrospective series. One small prospective randomized trial has compared surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy and demonstrated equivalent 10-year event-free survival (EFS) with surgery and radiotherapy but improved EFS with chemotherapy. No difference in overall survival (OS) with any of the treatments was reported.30

Radiotherapy is a valid option for MALT lymphoma; however, it is not universally used. It provides local control and potential cure in localized gastric stage IE and II1E disease with 5-year EFS of 75–90% reported in retrospective studies.35–37 However, the irradiation field is potentially large as it must include the whole stomach, which can vary greatly in size and shape. Irradiation techniques have improved considerably in the last 20 years, including treating the patient in a fasting state, decreasing the irradiated field and required dose. The moderate dose of 30 Gray (Gy) of involved-field radiotherapy administered in 15 fractions (doses) can be associated with tolerable toxicity and adequate outcomes. Hence, radiotherapy is an acceptable approach for local disease where antibiotic therapy has failed, or is not indicated; however, its use in individuals is determined by the radiation field. Evidence also suggests that radiotherapy can be utilized to control localized relapses outside the original radiation field.30

MALT lymphoma is exquisitely chemotherapy sensitive. Chemotherapy is reserved for those with disseminated disease at presentation or lack of response to local treatment. Rituximab, the anti-CD20 chimeric antibody, is a key component of therapy. Responses vary from 55% to 77% with monotherapy and 100% in combination with chemotherapy.38–43 Oral alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide or chlorambucil have been administered for a median duration of 12 months with high rates of disease control (CR up to 75%) but appear not to be active in t(11;18) disease.44,45 The purine nucleoside analogs fludarabine and cladribine also demonstrate activity,42,46 the latter conferring a CR rate of 84% (100% in those with gastric primaries) in a small study.47 A pivotal study of rituximab plus chlorambucil compared with chlorambucil alone (IELSG-19 study, n = 227) demonstrated a significantly higher CR rate (78% vs. 65%; p = 0.017) and 5-year EFS (68% vs. 50%; p = 0.024) over chlorambucil alone. However, 5-year OS was not improved (88% in both arms).48 First-line treatment of choice is generally rituximab in combination with single alkylating agents or fludarabine, or a combination of all three drugs. The final results of this study, including the later addition of a rituximab-alone arm, are pending.

Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease

IPSID is a subtype of MALT lymphoma occurring only in the small intestine, which was previously called alpha-heavy chain disease, due to the expression of monotypic truncated Ig α-chain in the absence of associated light-chain expression, or Mediterranean lymphoma because of its distinct geographical distribution with cases occurring almost exclusively in the Middle East, areas bordering the Mediterranean sea, and Cape region of South Africa. It has recently been associated with C. jejuni infection.49,50 As opposed to “Western” MALT lymphoma of the intestine, which occurs predominantly in elderly patients, the median age at diagnosis of IPSID is 25–30.51 There is no one gender preponderance.

Clinical manifestations include malabsorption, diarrhea, abdominal pain with obstruction, and, in more advanced disease, ascites. Involvement of peripheral nodes, the spleen, bone marrow, or other organs is uncommon except in advanced disease.52,53 Diagnosis is made via endoscopy or laparotomy, with solitary primary lesions occurring in most cases. The histological features are similar to MALT lymphoma of other sites; however, these usually demonstrate prominent plasmacytic differentiation.54 The serum contains detectable alpha-heavy chain proteins in 20–90% of patients. IPSID does not harbor the t(11;18) translocation seen in other MALT lymphomas.24,53,55,56

Treatment recommendations are based on small series in the literature but include antibiotics such as tetracycline and metronidazole for early-stage disease and anthracycline-based chemotherapy in addition to antibiotics for advanced disease.55,57,58 Total abdominal irradiation has been reported to achieve remissions. Surgery is reserved for mechanical obstructions in the treatment setting, but can be necessary to obtain a diagnosis.

Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma

Epidemiology

Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is a rare, aggressive intestinal T-cell lymphoma arising in the intraepithelial T lymphocytes (IELs) comprising less than 1% of NHL.6 Eighty to ninety percent of EATL (Type I) is associated with celiac disease (CD), with Type II EATL occurring sporadically with differing morphological and immunophenotypic features, suggesting a possible separate disease entity.54 It was initially believed that the malabsorption associated with EATL was a consequence of the intestinal lymphoma, but subsequently proven that malabsorption (CD) was the preceding condition leading to lymphoma.59,60 The term EATL was first used in 1986.61

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree