- Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are heterogeneous and management depends on the site of primary.

- Metastatic NETs can be nonfunctional or functional: carcinoid syndrome with midgut NETs and various secretory syndromes with pancreatic NETs.

- The biology of NETs and prognosis is reliably predicted by grade, which affects management choice.

- First-line therapy for most metastatic/advanced NETs are somatostatin analogs if demonstrated on OctreoScanTM (or Gallium-68 PET); or chemotherapy with some pancreatic NETs.

- Various options exist for further therapy including peptide receptor targeted therapy, transarterial hepatic embolization, chemotherapy, and new small molecules.

Epidemiology

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are malignant transformations of cells of the diffuse neuroendocrine system (DNES), which comprises a variety of neuroendocrine cells scattered throughout the body. The original name, “carcinoid” (carcinoma-like), proposed by Oberndorfer in 1907,1 is often paired with primary site, for example, ileal carcinoid, gastric carcinoid, but this is now an outdated term.

Commonly thought to be rare, incidence rates in the 1980s reported fewer than 2 per 100,000 per year.2 Recent data, however, suggests an incidence of 5.25 per 100,000.3 This increase, particularly in gastroenteropancreatic NETs (GEP-NETs), probably reflects changes in detection, better pathological expertise and awareness, incidental findings on imaging/endoscopy rather than increasing burden, since GEP-NETs were found in up to 1% of necropsies,4 more than expected.

NETs are a heterogeneous group of tumors arising from midgut, pancreas, stomach, lungs, or colorectum, exhibiting diverse biological behavior from relatively indolent to highly aggressive cancers. Given heterogeneity in survival, it is not surprising that recent prevalence rates have been reported as up to 35 per 100,000, more common than that of most gastrointestinal cancers including hepatobiliary, esophageal, and pancreatic carcinomas.3

Survival data for NETs are difficult to interpret from historical studies due to heterogeneity in terms of type and grade of NET and difficulties in formulating globally accepted classification systems. Overall 5-year survival of all NET cases in the largest series to date was 67.2% with the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) data reporting mean 5-year survival of 58.4% across 49,012 patients with NETs.5

Survival varies depending on grade and site of tumor. Pancreatic NET 5-year survival from the SEER registry was only 37.6%, but within this group, survival heterogeneity existed. Survival ranged from 30% for somatostatinomas to 95% for insulinomas at 5 years. Five-year survival for other GEP-NETs were 68.1% for midgut NETs, 64.7% for gastric NETs, 81.3% for appendix NETs, and 88.6% for rectal NETs.

Recent data have shown that 20% of patients with NETs develop other cancers, one-third of which arise in the gastrointestinal tract.5

Diagnosis

GEP-NETs can be asymptomatic, diagnosed incidentally on imaging, but may produce specific symptoms. These symptoms may relate to physical compression or obstruction of viscera by the tumor (pain, nausea, vomiting) or particularly in the case of NETs, related to secretion of hormones. The syndromes described below are typically seen in patients with secretory pancreatic tumors (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1 Syndromes associated with pancreatic NETs.

| Tumor | Symptoms | Malignancy |

| Insulinoma | Confusion, sweating, dizziness, weakness, unconsciousness, relief with eating | 10% of patients develop metastases |

| Gastrinoma | Zollinger–Ellison syndrome of severe peptic ulceration and diarrhea | Metastases develop in 60% of patients; likelihood correlated with size of primary |

| Glucagonoma | Necrolytic migratory erythema, weight loss, diabetes mellitus, stomatitis, diarrhea | Metastases develop in 60% or more patients |

| VIPoma | Werner–Morrison syndrome of profuse watery diarrhea with marked hypokalemia | Metastases develop in up to 70% of patients; majority found at presentation |

| Somatostatinoma | Cholelithiasis, weight loss, diarrhea, and steatorrhea. Diabetes mellitus | Metastases likely in about 50% of patients |

| Nonsyndromic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor | Symptoms from pancreatic mass and/or liver metastases | Metastases develop in up to 50% of patients |

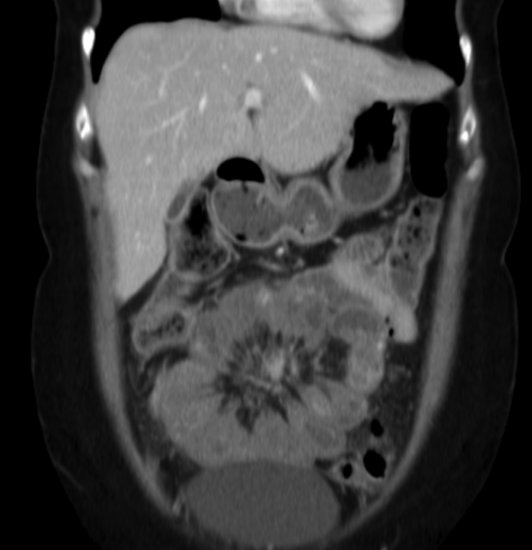

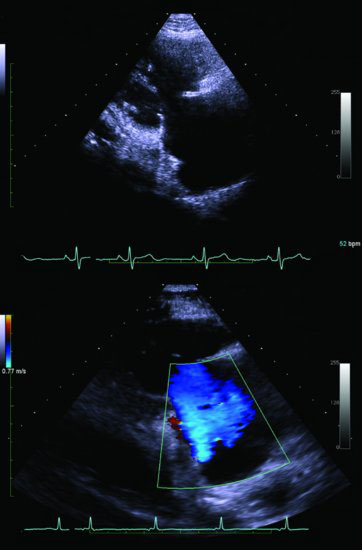

“Carcinoid syndrome,” characterized by diarrhea and flushing, is commonly a result of metastases to the liver, usually from a midgut NET, with release of hormones (serotonin and other vasoactive compounds) directly into the systemic circulation. In addition, midgut NETs may be associated with desmoplasia manifesting as intestinal (Figure 9.1), ureteric obstruction, or even heart failure associated with cardiac valve fibrosis (Figures 9.2 and 9.3). NETs are often diagnosed with advanced disease after numerous years of misdiagnosis with, for example, irritable bowel syndrome.

Figure 9.1 CT scan demonstrating midgut neuroendocrine tumor: mesenteric mass with surrounding desmoplasia and tethering of small intestine with dilated fluid-filled small bowel loops.

Figure 9.2 Echocardiogram demonstrating carcinoid heart disease involving the tricuspid valve. Above: parasternal right ventricular inflow view demonstrating fixed, thickened, and retracted tricuspid valve leaflets and associated chordae. Below: Color Doppler showing free-flowing, severe tricuspid regurgitation through non-coapting valve leaflets into a dilated right atrium.

Figure 9.3 Echocardiogram demonstrating carcinoid heart disease involving the pulmonary valve. Above: parasternal short-axis view of the pulmonary valve demonstrating fixed, thickened, and retracted valve leaflets that fail to coapt, resulting in the valve remaining in a semi-open position. Below: color Doppler showing a severe jet of pulmonary regurgitation in diastole.

The diagnosis is therefore based on clinical symptoms, hormone profile, radiological and nuclear medicine imaging, and histological confirmation. The gold standard in diagnosis is detailed histopathology and this should be obtained whenever possible.

Blood and urine investigations

In addition to general hematological and biochemical tests such as full blood count, parathyroid hormone (PTH), thyroid function tests (TFTs), calcitonin, prolactin, CEA, α-fetoprotein, and β-human chorionic gonadotrophin, there are a number of specific biochemical tests. Measurement of circulating and urinary peptides and amines in patients with NETs can assist in making the initial diagnosis and may provide prognostic and predictive information.

The most commonly used and clinically useful “general” NET-circulating marker is plasma chromogranin A (CgA).6,7 It is raised in many NETs with a sensitivity and specificity ranging from 27% to 95% depending on the type of assay used.8,9 It is also useful as a prognostic marker: patients with a CgA greater than 5000 μg/L have a 5-year survival of only 22% compared with 63% for patients with CgA less than 5000 μg/L.10

Fasting hormones should be evaluated in pancreatic NETs in order identify the syndromes in Table 9.1. Further dynamic testing, including prolonged fast (insulinoma) or secretin test (gastrinoma), should be performed depending on the syndrome suspected. Intrinsic factor and parietal cell antibodies are positive in gastric NETs associated with atrophic gastritis.

Twenty-four-hour urinary 5-hydroxy-indoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) is a product of serotonin metabolism, often raised in midgut NETs, particularly if symptoms of carcinoid syndrome are present. Care must be taken when evaluating urinary 5-HIAA as certain foods taken just prior to, or during collection, can alter results. Banana, avocado, aubergine, pineapple, plums, walnut, paracetamol, fluorouracil, methysergide, naproxen, and caffeine may cause false-positive results. Levodopa, aspirin, adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), methyldopa, and phenothiazines may give false-negative results.

Radiology and endoscopy

Primary midgut NETs may be difficult to identify on imaging as they are often small. Frequently, however, a lymph node metastasis with surrounding desmoplasia, a “mesenteric mass,” can be demonstrated. Pancreatic NETs and some NET liver metastases can be diagnosed on CT or MRI due to their hypervascular nature, especially with several contrast-enhancement phases.11 MRI may be useful in characterizing small liver metastases, and also in young patients requiring repeated imaging.

Gastric NETs are often found incidentally at upper gastrointestinal endoscopy as polyps in the stomach fundus or body (with associated atrophic gastritis and hypergastrinemia in Type-I gastric NETs). Gastric, duodenal, rectal, and colonic NETs are diagnosed at endoscopy with CT utilized to detect regional and distant metastases for staging in these cases. However, MRI or endorectal ultrasound may be of more benefit in the latter two to ascertain local invasion. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can be performed to assess local invasion of gastric and duodenal NETs and for identifying and aspirating pancreatic lesions for tissue diagnosis. EUS is a useful diagnostic investigation in patients with suspected pancreatic NETs (mean sensitivity 90%).12,13 Its sensitivity may be less with extra-pancreatic gastrinomas (80% of gastrinomas in MEN1 are found in the duodenum) for which an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and CT/MRI should be performed.14

For clinical and research purposes, observing or monitoring response to therapy can be assessed by RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors).

Nuclear medicine imaging

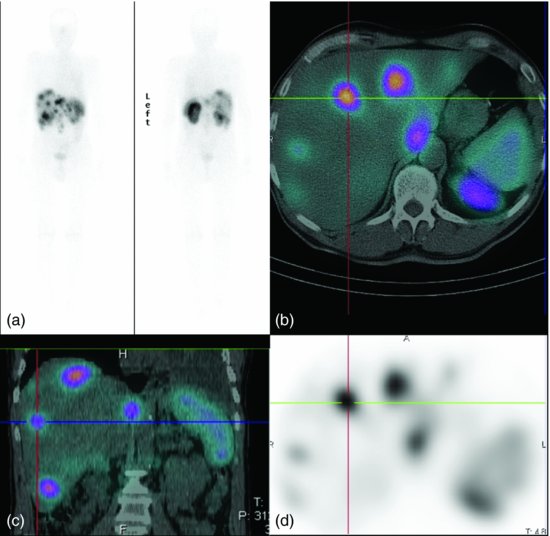

NETs express somatostatin receptors (SSTRs), which led to the development of radiolabeled somatostatin analogs (SSA) for diagnosis and therapy. There are five SSTR subtypes (SSTR1–5) with SSTR2 and SSTR5 expressed in at least 80% and 77% of gastrointestinal NETs, respectively.15,16 With the exception of insulinomas (only 50% express SSTR2), somatostatin scintigraphy (with OctreoscanTM) is the mainstay of staging and may assist in localizing primary lesions in GEP-NETs17,18 (Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4 Whole body OctreoScan™ supplemented with SPECT/CT of liver and upper abdomen demonstrating focal uptake of tracer in liver lesions on whole body coronal image (a), SPECT/CT trans-axial (b) and coronal slices (c) and OctreoScan™ axial image (d).

Unlike adenocarcinomas, PET–CT with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) is not very useful, but it can assess the extent of high-grade NETs or other lesions suggestive of coexistent cancers.19 Increasing use of PET with compounds such as 68Gallium-DOTA-Octreotate and 68Ga-DOTA-Octreotide and more recently 68Ga-DOTANOC have been found to be sensitive for NETs due to detection of more SSTR subtypes and enhanced affinity compared with OctreoScanTM.19 These characterize metastases, assess extent of disease, and locate primary lesions (Figure 9.9).

Frequently, patients present with metastases without an obvious primary. Investigations for localizing the primary site may include EUS; CT of chest (bronchial carcinoid), abdomen, and pelvis; endoscopy (colonoscopy, gastroscopy, video capsule enteroscopy); and nuclear medicine imaging. In one series, primary tumors were localized in 81–96% of cases using radiological and nuclear medicine imaging.20

Pathology

Historically, prognostic classifications in NETs have proven difficult due to complexity of different classification systems. NETs should be classified according to the tumor node metastasis classification system proposed by the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) for foregut, midgut, and hindgut NETs21,22 that have proved valid and applicable.23–25 Alternatively, the World Health Organization (WHO) 2010 classification may be used.26

Classification is made according to site of primary tumor, size, invasion to muscularis propria, and histological grade. The latter is particularly useful prognostically. It uses mitotic count per 10 high power fields (HPF) or the Ki-67 proliferation index to group NETs into:

- low (G1) (<2 mitoses/10 HPF or Ki-67 ≥2%);

- intermediate (G2) (2–20 mitoses/10 HPF or Ki-67 3–20%);

- high (G3) (>20 mitoses/10 HPF or ≥20%).

Ki-67 proliferation index should be assessed in 2000 tumor cells in areas where the highest nuclear labeling is observed and mitoses in at least 40 HPF.

Five-year survival rates for pancreatic NETs are 94%, 63%, and 14% for low-, intermediate-, and high-grade tumors, respectively.27 For midgut NETs, the figures are 95%, 82%, and 51%, respectively.24

All suspected NET samples should undergo immunostaining with a panel of antibodies to general neuroendocrine markers.28 These include PGP9.5, synaptophysin, CgA, and MIB-1 (to generate Ki-67 index). High-grade tumors indicate a poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma, showing significantly reduced CgA expression while maintaining intense staining for synaptophysin. Where a syndrome of hormone excess is present, the tumor can also be confirmed as the source using antibodies to the specific hormone(s).

Prevention

There is no evidence to date to suggest measures that can be taken to prevent NETs. However, in a case-control study, a family history of cancer was a significant risk factor for all NETs and a history of diabetes mellitus for gastric NETs.29 Smoking and alcohol consumption were not associated with NET development.

Cancer management

General objectives

Wherever possible, in localized cases, surgery should be attempted to obtain curative resection. In some cases with liver metastases, where the primary is resectable, resection of the liver metastases +/− ablation of nonresectable lesions may be considered as a curative approach.

Metastases are often present at the time of diagnosis, where curative resection is usually not possible, and when surgery is undertaken, it can be considered palliative in view of residual disease. The aim of treatment is thus to control tumor growth, prolong survival, and improve symptoms (including those from excess hormone secretion) and quality of life. Treatment choice depends on site of primary, grade, comorbidities, patient tolerability, and availability of options. Management should be guided by guidelines produced by the ENETS.30–32

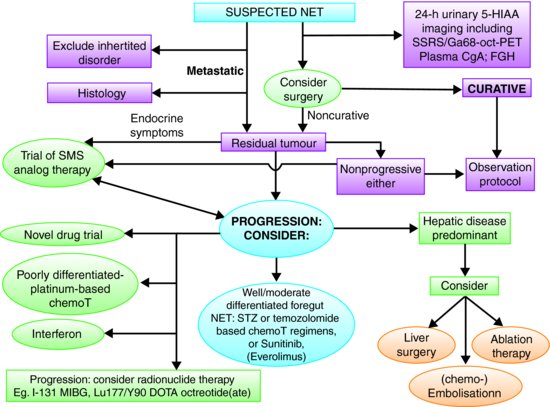

In low- and intermediate-grade metastatic midgut NETs, SSAs are the mainstay of treatment. Until recently, these were only indicated in functioning midgut NETs with “carcinoid syndrome,” but recent evidence suggests that their use can be extended to nonfunctioning midgut NETs to prolong progression-free survival (PFS).33 For well-differentiated pancreatic NETs, chemotherapy is often the first-line choice of therapy with good evidence of efficacy34 and it is the first-line treatment for poorly differentiated or high grade NETs. All therapeutic options should be discussed within a multidisciplinary team. A general algorithm is shown in Figure 9.5.

Figure 9.5 Algorithm for the management of patients with NETs. 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid; SSRS, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy; CgA, chromogranin A; STZ, streptozocin; MIBG, metaiodobenzylguanidine; chemoT, chemotherapy; Ga68-oct PET, Gallium68-DOTA-Octreotate positron emission topography. (Adapted from Ramage et al.47 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Limited.)

Surgery

Emergency surgery

Patients with midgut NETs may often present in the emergency situation with intestinal obstruction caused by peritumoral fibrosis. After emergency laparotomy, the subsequent diagnosis of midgut NET is made on the surgical specimen. However, the tumor may be deemed unresectable and an intestinal bypass procedure performed. Following definitive histopathology, a limited small bowel resection for an obstructing tumor can be followed at a later date by elective surgery to remove further small intestine or nodal disease.

Another common emergency situation may arise whereby patients presenting with appendicitis have their NET diagnosed on the surgical specimen after appendicectomy is performed. Further management may be required as explained later. Rarely, a hindgut NET may present with large bowel obstruction with emergency resection and Hartmann’s procedure. Similarly, the diagnosis of NET is made on the surgical specimen.

When a functioning tumor is diagnosed before surgery, there is a risk of carcinoid crisis when the tumor is operated upon. This should be prevented by the administration of continuous intravenous Octreotide at a dose of 50 μg/hour for 12 hours prior to and at least 48 hours after surgery.35 Similarly, prophylaxis with glucose infusion for insulinoma surgery, proton pump inhibitor, and Octreotide for gastrinomas may be required.

Stomach

There are three types of gastric NET that are usually found incidentally as polyps during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Management is dependent on the type as suggested by the ENETS guidelines.36

Type-I gastric NETs are associated with hypergastrinemia and chronic atrophic gastritis. They present as polyps resulting from the hypergastrinemia causing hyperplasia and proliferation of enterochromaffin-like cells (ECL cells). Their metastatic potential is very low and in the majority of cases <10 mm; only annual endoscopic surveillance is required with serial mucosal biopsies taken due to the risk of gastric adenocarcinomas developing from intestinal metaplasia.37 In larger tumors of 10–20 mm, EUS is required to assess depth of invasion. Endoscopic resection is recommended for up to 6 polyps not involving the muscularis propria. For other patients with polyps over 20 mm, local surgical tumor resection should be considered with antral resection to avoid repeated gastrin stimulation of gastric ECL cells. This is effective in 80% of Type-I tumors.38

Type-II gastric NETs are caused by hypergastrinemia due to Zollinger–Ellison syndrome almost exclusively in multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) Type I.39 These can be more aggressive especially in those greater than 20 mm. Endoscopic or local resection may be required as with Type-I gastric NETs. Consideration should be taken to search for and resect the gastrin-secreting primary tumor. Annual endoscopic surveillance is recommended with mucosal resection of polyps over 10 mm.

Type-III gastric NETs are more aggressive. Local endoscopic or surgical excision may be appropriate for lesions <20 mm with management of larger lesions similar to that for gastric adenocarcinomas—partial or total gastrectomy with lymph node dissection. EUS in addition to CT/MRI is important in staging.

Midgut

Midgut NETs are usually over 2 cm at diagnosis, having invaded the muscularis propria and frequently metastasized to regional lymph nodes. For those with localized NETs of the jejunum–ileum, surgery should be curative. Resection of the primary, either through open or laparoscopic approach, should adhere to oncological principles and should involve lymph node clearance, aiming to preserve vascular supply and limit intestinal resection.40 At laparotomy, the small intestine should be explore for a second primary that can occur in 30%. There is a lack of positive phase III studies in an adjuvant situation.

In patients with limited liver metastases, curative resection involving removal of the primary, regional lymph nodes, and resectable liver metastases is possible in up to 20% of patients.40,41 Further evidence of surgery for liver metastases is given in Section “Liver metastases.”

In the presence of unresectable metastases or unresectable small intestinal NET, resection of jejunal-ileal NETs should be considered to prevent future intestinal obstruction or ischemic complications due to the desmoplastic reaction or compression of the mesenteric vein due to tumor mass.30 Surgery should be performed according to oncological principles and may include resection of nodal metastases with associated desmoplasia. This has been reported to increase survival benefit from 69 to 130 months.42 Commonly, the associated desmoplasia may preclude tumor resection, and in these cases, bypass procedures should be undertaken to prevent obstructive symptoms. Palliative or cytoreductive surgery can be considered in patients in whom 90% of the tumor load can be removed safely. This may involve resection of the primary with locoregional metastases or intra-abdominal debulking or synchronous resection of primary and liver metastases.43

Pancreas

Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal, or even total pancreatectomy may be appropriate in functioning and nonfunctioning pancreatic NETs. Localized tumors >2 cm should have aggressive surgery and resection of nearby organs if required.44 With tumors <2 cm, surgical cure needs to balanced with postoperative complications and morbidity due to lack of evidence. Small, easily accessible tumors can be treated with enucleation or middle pancreatectomy. The laparoscopic approach may be considered in expert hands for insulinomas and small nonfunctioning tumors in the body or tail. Resection of locally advanced nonfunctioning pancreatic NETs may prolong survival with a 5-year survival up to 80%.45

With regard to metastatic nonfunctioning pancreatic NETs, resection of the primary fails to improve survival but may reduce symptoms in hormonally active primary tumors.45

Patients with MEN1 often have multiple small NETs throughout the pancreas and gastrinoma patients throughout the duodenum. However, fit patients with sporadic gastrinomas with resectable disease should be considered for surgical exploration for cure.

Surgery for liver metastases is discussed in Section “Liver metastases.”

Colorectum

Surgical management of colonic NETs is similar to colonic adenocarcinomas due to aggressive behavior. Since most invade the muscularis propria and are greater than 2 cm in diameter, colectomy and oncological resection of lymph drainage is recommended.46 This may also be indicated to prevent intestinal obstruction or ischemic complications especially if there is desmoplastic reaction in proximal colonic lesions similar to that of classical midgut NETs. Liver metastases are managed as discussed in Section “Liver metastases” and this is where management differs from colonic adenocarcinomas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree