Abdominal bloating

Subjective sensation of excessive gas/flatulence, fullness, abdominal hardness or tightness or the feeling of abdominal inflation or swelling

Abdominal distension

Actual increase in abdominal girth

Functional abdominal bloating

Recurrent complaints of bloating with or without associated abdominal distension and absence of criteria for a diagnosis dyspepsia, IBS, or other functional gastrointestinal disorder

Epidemiology

Abdominal bloating is a common and bothersome symptom and is often ranked more troublesome than abdominal pain. It typically worsens as the day progresses, especially after meals, and improves overnight. Defecation and passage of gas can also afford some relief. Bloating affects between 24 and 97 % of patients with FGIDs and also commonly occurs in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease, premenstrual syndrome, and intestinal dysmotility. It is considered a diagnosis per se (i.e., functional bloating) in patients who do not fulfill Rome criteria for other FGIDs (Table 10.1), with a prevalence ranging from 3 to 30 %. A significant but variable proportion (8–36 %) of subjects in the general community experience abdominal bloating. These wide variations in prevalence rates are undoubtedly influenced by the definition of bloating used as it is ambiguous and can mean different things to both patients and doctors. IBS patients with bloating consult more and have worse quality of life than those IBS patients without bloating. Despite this, bloating alone is seldom a reason for patients to seek health care and, compared with other functional and organic gastrointestinal disorders, presents only a moderate impact on the subject’s quality of life and productivity.

The terms bloating and distension have often been considered synonymous; however, this is to be discouraged. Multiple surveys and studies objectively measuring abdominal girth (i.e., distension) over 24 h have shown that the symptom of bloating is often not accompanied by an objective increase in abdominal girth. Studies using the technique of abdominal inductance plethysmography (see Fig. 10.1) have shown that significantly more constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C) patients (60 %) exhibit diurnal changes in girth beyond the normal reference range seen in healthy volunteers than diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) patients (40 %) with the average increase being about 3–4 cm but in some patients up to 10–12 cm (see Fig. 10.2). For reasons that remain unclear, the severity of the symptom of bloating only correlates with objective distension in IBS-C and not IBS-D patients. Interestingly, bloating alone has been reported to be more prevalent than distension in patients with functional constipation. Both women in health and with FGIDs are more likely to report distension and/or bloating than men. Other factors associated with an increased risk for distension over bloating alone include young age, presence of somatic symptoms, and multiple overlapping GI diagnoses.

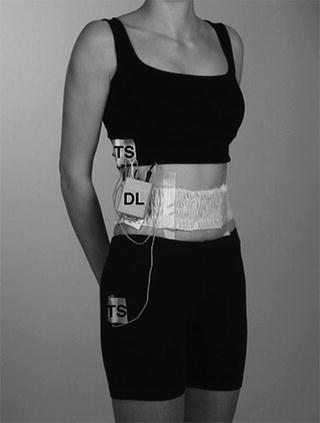

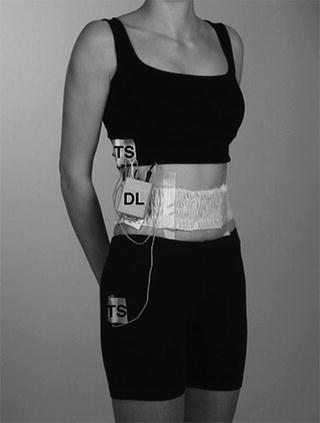

Fig. 10.1

Photograph of a subject wearing the ambulatory abdominal inductance plethysmography (AIP) equipment incorporating a belt into which is sewn a wire in zigzag fashion to allow for expansion and connected to an oscillator secured under the belt, data logger (DL), and tilt switches (TS) to record posture. It works on the principle that a loop of wire forms an inductor, the inductance of which is dependent on the cross-sectional area of the loop, from which circumference can be calculated. Reproduced with kind permission from Neurogastroenterol Motil 2005; 17: 500–511

Fig. 10.2

Typical recording of abdominal girth over 24 h in a patient with IBS-C. Numbers across the top of the girth recording are the bloating scores (scale 0–5) obtained from a diary. Note how in this IBS-C patient girth changes tend to relate to the sensation of bloating, the increase in girth with meal ingestion, and the reduction in girth during sleep. Reproduced with kind permission from Gastroenterology 2006; 131:1003–1010

Pathophysiology

Distension

An understanding of the mechanisms associated with abdominal distension has greatly advanced in recent years. Using abdominal inductance plethysmography, it has been shown that IBS-C patients who have a diurnal change in girth beyond the 95th percentile limit for healthy volunteers (i.e., distenders) have slower gastrointestinal transit, particularly of the colon, compared with those who have changes in girth within the normal range (i.e., non-distenders). Moreover, abdominal distension directly correlated with orocecal and colonic transit times and with the hardness of stool. Accelerating transit with the probiotic Bifidobacterium lactis DC-173 010 has been shown to correlate with an improvement in abdominal girth, suggesting that gastrointestinal transit plays a role in abdominal distension.

The mechanism whereby intestinal content (e.g., solid, liquid, gas) leads to distension, however, appears to vary depending on the patient group assessed. In healthy volunteers, increased intra-abdominal content is associated with (1) relaxation and ascent of the diaphragm to enlarge the abdominal cavity and thus to accommodate the abdominal load, (2) contraction of the anterior abdominal muscles (upper and rectus, external oblique with the exception of the internal oblique which in an upright position is already contracted to counteract gravitational forces and support abdominal contents) to prevent excessive abdominal distension, and (3) expansion of the chest wall to compensate for the reduction in lung height caused by diaphragmatic ascent preserving air volume. This integrated abdominothoracic response appears to be related to volume rather than rate of expansion. In patients with intestinal dysmotility, a similar process takes place with the volume of pooled intestinal contents (particularly in the small bowel) directly correlating with ascent of the diaphragm and the degree of anterior protrusion of the abdominal wall. Thus, in patients with intestinal dysmotility, distension appears to be the result of a true increase in abdominal contents (see Fig. 10.3). These observations, however, contrast with those seen in patients with FGIDs. In patients with IBS and functional bloating, the degree of abdominal distension to a given intestinal load is significantly greater than that seen in patients with intestinal dysmotility or healthy controls. This appears to be related to impaired contraction of the lower rectus and external oblique abdominal muscles, and paradoxical relaxation of the internal oblique muscle and descent due to contraction of the diaphragm (see Fig. 10.3). Similar observations have been made in patients with functional dyspepsia with the exception that only the upper anterior wall (upper rectus and external oblique) and not the lower muscles (lower rectus and internal oblique) relax to a given gastric load. The cause of this abdomino-phrenic dyssynergia in FGIDs remains unknown, but IBS patients with the greatest diurnal changes in abdominal girth often exhibit rectal in- or hyposensitivity.

Fig. 10.3

Mechanisms of distension. In FGID patients, abdominal distension is related to abdomino-phrenic displacement and ventro-caudal distribution of contents, whereas in intestinal dysmotility patients, distension involves a true increment in intestinal content and abdominal expansion. Note the descent (contraction) of the diaphragm in the FGID patient but ascent (relaxation) of the diaphragm in the dysmotility patient. The latter is accompanied by expansion of the chest wall to compensate for the reduction in lung height preserving its air volume. Reproduced with kind permission from Gastroenterology 2009; 136:1544–1551

Lastly, patients with non-diarrhea IBS and functional constipation who report abdominal distension (not objectively measured) have prolonged rectal balloon expulsion times, higher resting anal sphincter pressures, higher maximum anal sphincter squeeze pressures, and longer times to onset of anal sphincter inhibition during rapid inflation of rectal balloon, suggesting a potential role for abnormal anorectal function in the pathophysiology of abdominal distension.

Bloating and Gas (Without Distension)

Unlike patients with intestinal dysmotility who have significant pooling of gut contents, particularly gas in the small bowel, patients with FGIDs have no more gas in their intestines than healthy controls or patients with organic gastrointestinal disease (e.g., Crohn’s disease, colonic diverticulosis, peptic ulcer disease, GERD). Moreover, over ten times the normal amount of gas present in the gut, approximately 200 mL, can be infused into the intestine of healthy volunteers with less than a 2 cm change in girth, which is significantly less than the average 4 cm, and up to 10–12 cm seen in some IBS patients, suggesting that gas retention is not the cause of abdominal distension in these patients. Despite this, gas infused into the intestine of patients with IBS and functional bloating has been shown to be retained longer in the intestine and is not as well tolerated compared with similar gas loads infused in healthy volunteers. Patients with IBS-C retain gas longer than IBS-D patients, although the perception of the presence of the gas is greater in IBS-D. This may be related to the reduced transit and motility seen in IBS-C but increased prevalence of visceral hypersensitivity seen in IBS-D. Indeed, it has been shown that the sensation of bloating in the absence of abdominal distension is associated with increased visceral sensitivity compared with those who bloat and distend, with over 80 % of IBS patients who bloat alone exhibiting rectal hypersensitivity. Thus, ineffective gas propulsion and retention in patients with functional bowel disorders, particularly in a sensitized gut, may be responsible for the sensation of bloating and gas without visible distension.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree