(1)

Department of Child Health, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA

Chapter Outline

Introduction

Physiologic Anatomy

Sensory

Motor

Visceral

Somatic

Internal anal sphincter

External anal sphincter

Reflexology

Gastro-colic reflex

Recto-sphincteric reflexes

Sampling reflex

Rectal inhibitory reflex

Pelvic floor reflexes

Postural reflex

Continence-preserving reflex

Closing reflex

Cutaneo-anal contractile reflex

Sequence of Events during Defecation and Continence

The Development of Toileting Skills

Uncomplicated toilet learning

Anxiety and toilet learning

Piaget’s childhood animism

Pelvic Floor Motility: coordinated and dyssynergic;

Hinman’s Syndrome

Philosophical Context of Clinical Management of Disorders of Elimination

Diagnostic Techniques for Disorders of Defecation

Functional Disorders of Defecation Syndromes

Functional Fecal Retention Syndrome (FFRS)

Emerging

Established

The mechanism of soiling in FFRS

Management and the nature and pace of recovery

The “retentive crisis” and its importance

Problems in the Differential Diagnosis of Functional Fecal Retention Syndrome

Hirschsprung’s Disease

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B

Pelvic tumor

Stooling hiatuses in breast fed infants

Anal ectopy, anal stenosis

Anal trauma, perianal dermatoses

Masturbatory posturing

Functional Nonr–etentive Fecal Soiling (FNRFS)

Diagnosis and management

Differential diagnosis: Neuropathic fecal and/or urinary soiling

Diaper Dependency

permitted

contentious

Infant Dyschezia

Introduction

Disorders of Defecation include inadequate evacuation of stool and/or age-inappropriate fecal soiling. Children with these symptoms may have abnormalities in the anatomy or physiology of the ano-rectum and/or psychological or developmental impediments to normal toileting.

About 25 % of patients referred to pediatric gastroenterologists suffer from disorders of defecation [1–3]. Functional disorders are 50–100 times more prevalent than organic disorders of defecation [4]. About 2 % of all children are troubled with fecal soiling at some time during primary school.

The following is a review of the physiological anatomy of the apparatus of defecation and fecal continence, the developmental process by which toileting skills are acquired, problems of disordered pelvic floor motility, followed by a review of functional disorders of defecation, their differential diagnoses, and their management.

Physiologic Anatomy of the Apparatus of Defecation and Fecal Continence [5–7]

The physiological apparatus that permits sensing, discrimination, withholding, and controlled evacuation is comprised of the anus, pelvic floor, rectum, colon, abdominal muscles, diaphragm, and glottis. It can be understood in terms of sensory and motor functions. (Figure 2.1)

Fig. 2.1

Coronal section of the lower rectum, anus, and pelvic floor: The apparatus of defecation and fecal continence, sensory and motor elements

Sensory Aspects

The urge to defecate has visceral sensory and somatic sensory components. The visceral sensory component is mediated by tension receptors within the colo-rectal wall and within the surrounding pubo-rectalis portion of the levator ani muscle at the level of the ano-rectal junction. Stool or gas entering the rectum distends it, thereby increasing the mechanical tension within the rectal wall and the surrounding pubo-rectalis muscle fibers [8] where it is appreciated as the urge to stool. A sense of pelvic fullness progressing to colicky pain is felt when a progressive stretch stimulus is applied 15 cm or more above the anus [9]. A feeling of pressure on the perineum and a sense of impending defecation are felt when distention is applied closer to the anus [10]. Mechanical tension (and therefore afferent sensory excitation) is heightened when stretch is applied rapidly rather than gradually [11]. Therefore, the sensation of fullness may progress to intense pain when the colo-rectum is rapidly filled with air or fluid, as during an enema or acute diarrhea. By contrast, the gradual rectal distention caused by chronic stool withholding is associated with comparatively less rectal pain or discomfort, although acute colicky pain can occur during bouts of active gut wall contractions in a patient with a partially obstructive intra-rectal fecal mass [12].

The somatic sensory component of the urge to defecate involves receptors for touch, pain, temperature, pressure, and friction located within the anoderm [5, 13]. When stool or flatus comes into contact with the upper end of the anoderm, nerve impulses traverse the somatic sensory fibers within the pudendal nerves en route to the CNS where imminent incontinence is appreciated. Anal sensory receptors allow the discrimination of flatus vs. solid stool [14, 15].

Motor Aspects

Fecal continence results from resistance to outflow created by two muscle groups: the smooth muscle of the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and the striated muscles of the pelvic floor and external anal sphincter (EAS) The IAS is the thickened terminal portion of the smooth muscle of the rectal wall. It extends part way down the anal canal and is surrounded by the EAS. The relation of the two sphincters can be likened to a funnel within a funnel. The caudal limit of the IAS can be felt by digital palpation of the inter–sphincteric line part way up the anal canal. The IAS is innervated by the enteric nervous system and is not under voluntary control. Its principal reflex activity is relaxation. It contributes 5 % of the occlusive pressure of the anal canal at rest [16, 17]. The striated muscle of the EAS, levator ani, and the rest of the pelvic floor is innervated by the pudendal, third and fourth sacral nerves. They are under voluntary control, tend to act in unison, and provide the principle barrier during voluntary withholding when continence is threatened.

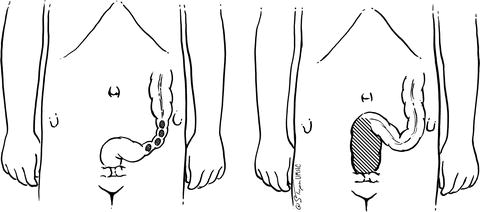

The rectum exits the pelvis via the anal canal which passes thru an elliptical opening in the mid-sagittal plane of the levator ani muscles at the level of the recto-anal junction [5]. Simply stated, the pubo-rectalis portion of the levator ani and upper part of the EAS are a unit, anatomically and functionally [18]. The pubo-rectalis is a U-shaped sling that originates from the posterior surface of the pubic bone and extends along the sides and back of the ano-rectal junction (Fig. 2.2). This sling pulls the ano-rectal junction forward and upward creating the ano–rectal angle which keeps stool from entering the anal canal. When imminent but unwanted incontinence of stool or flatus occurs, the sling contracts above the level of its resting tension (“squeeze”) thereby pulling the upper end of the anal canal further forward and upward, making the ano-rectal angle more acute, elongating the anal canal, and occluding its lumen. During normal defecation, the sling relaxes below its level of resting tension allowing the ano-rectal angle to become less acute, the anal canal to shorten and its lumen to more easily open, thereby lessening the mechanical resistance to passage of stool or flatus [5, 18, 19].

Fig. 2.2

Mid-sagittal diagram of the pubic bone, ano-rectum, and ano-rectal angle with the pelvic floor: at rest; during maximum contraction to prevent unwanted defecation (“squeeze”); and during defecation

Reflexology of the Colo-Rectum, Anal Sphincters, and Pelvic Floor

Although the pelvic floor and EAS muscles can be contracted and relaxed voluntarily, the motor activities that permit continence and defecation also involve reflex activity of the colon, rectum, anal sphincters, and pelvic floor [14, 15]. The passage of chyme from stomach to duodenum induces mass movement within the colon which propels stool into the rectum. Accumulation of withheld stool in the rectum slows propulsive motility in the right colon and sigmoid [20] and, in at least one instance, has been shown to result in retrograde movement of recto-sigmoid contents back up to the distal transverse colon [21]. In addition to its effects on colon motility, rectal distention slows gastric emptying and small bowel transit [22]. The appetite-suppressive effect of delayed gastric emptying and the hardening of stool that results from slow transit and rectal stasis may contribute to the anorexia in children with fecal retention and the return of hunger following evacuation of a retained fecal mass.

Recto-Sphincteric Reflexes

The sampling reflex [ 15], also known as the recto-anal inhibitory reflex, is activated when stool or flatus enters the rectum in the amounts sufficient to stretch (i.e. increase mechanical tension within) the rectal wall. This causes a reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter lasting 8–20 s [23]. It permits stool to descend into contact with the upper anoderm, stimulating its tactile receptors, causing conscious awareness of imminent incontinence and permitting discrimination between stool and flatus [15]. This reflex is intrinsic to the ano-rectum and is not dependent on an intact spinal cord or extrinsic innervation.

The Rectal Inhibitory Reflex [9]

The rectal inhibitory reflex is felt as an uncontrollable urge to stool caused by massive rectal filling, such as occurs with high volume diarrhea or rapid administration of an enema. It can be understood as a culmination of progressive increases in the sampling reflex. Each time a substantial amount of stool enters the rectum causing the IAS to relax, continence is preserved by contraction of the pelvic floor and EAS. Continued rectal loading causes more prolonged, deeper relaxation of the IAS and contraction of the pelvic floor [16, 24]. Rectal loading can reach a point at which the IAS relaxation persists and the pelvic floor and EAS reverse their usual response; instead of tightening, they relax and their ability to preserve continence lapses [25]. The rectal inhibitory reflex loop is viscero-spinal, demonstrable in normal and paraplegic subjects. It probably is a major factor in “retentive posturing” behavior that is a feature of the functional fecal retention syndrome [26].

Pelvic Floor Reflexes

The muscles of the pelvic floor differ from most other skeletal muscles in that they contain not only “fast twitch” fibers which produce rapid, phasic contractions characteristic of skeletal muscles, but also “slow twitch” fibers which produce sustained contraction over relatively long periods [27]. Pelvic floor muscles remain partially contacted at rest and during sleep. They contract above their level of resting tension during continence-preserving actions and relax below resting tension during defecation [9].

The Postural Reflex [9]

The tonus of pelvic floor muscles results from a spinal reflex involving spinal segments below L-2. Waxing and waning contractility occurs during sleep and wakefulness. For example, entry of stool into the rectum may trigger IAS relaxation (the sampling reflex) that escapes conscious awareness, but nevertheless, causes contraction of the pubo-rectalis, which may also go unnoticed [28]. Indeed, except for the intention to defecate, micturate, or give birth, all activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure are accompanied by reflex contractions of the pelvic floor above the level of resting tension; talking, coughing, lifting—all elicit this unnoticed reflex.

The Continence-Preserving Reflex [9]

Events that create a sudden awareness of imminent incontinence trigger the continence-preserving reflex [9]. A sudden urge to defecate or urinate causes contraction of the pelvic floor. However, the levator ani fatigues after about a minute [5] and returns to its level of resting tension. When this occurs, a fecal bolus may either descend and remain in contact with the anoderm or it may remain higher in the rectum, out of contact with the anoderm. When the fecal bolus remains out of contact with the anoderm after levator relaxation, the anus’ somato-sensory component of the defecatory urge ceases (and, by the young child’s magical thinking, “it goes away”).

Whether or not this response to a sense of imminent incontinence is an inborn reflex or voluntary act is controversial [29]. Before toilet training, it is presumed that infants do not inhibit defecation or urination [30]. Toilet training induces a conditioned response to eliminative urges for the purpose of maintaining continence until the child can get to a toilet. Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that the usual response to the urge to eliminate is a pelvic floor, continence-preserving reflex acquired during toilet training. It is also subject to voluntary control during defecation or micturition [31].

The Closing Reflex

The closing reflex is another stimulus-induced contraction of the pelvic floor above its level of resting tension [32]. It expels stool passing through the anal canal during defecation. Like continence-preserving reflexes, it is “automatic,” but also subject to voluntary control. Sensory input for the closing reflex originates in the somato-sensory receptors of the anoderm. It is likely that visceral afferents from the rectum are also involved because the pubo-rectalis and EAS immediately contract when an inflated balloon within the rectum is suddenly deflated, suggesting that the closing reflex can occur when contents within the rectal lumen suddenly shrink.

The Cutaneo-Anal Contractile Reflex (“Anal Wink”)

Reflex contraction of the pelvic floor and EAS is triggered when a tactile or painful stimulus, e.g., an examining finger or pin prick, is applied to or near the perianal skin or anoderm [9, 23]. This motor response is the same as that of the continence-preserving reflex. Although the reflex action elicited in both cases is the same, the two reflexes serve different functions: the stimulus for the continence-preserving reflex is the threat of incontinence caused by increased intra-rectal pressure and stimulation of the anoderm; by contrast, the cutaneo-anal contractile reflex is nocicepetive, a protective response to actual or anticipated anal penetration or trauma. Both reflexes can be elicited in patients with spinal cord transections above the sacral level.

The Development of Toileting Skills

In order to understand aberrant toileting, it helps to appreciate the skills inherent in normal control and the processes by which they are achieved [33].

A normal infant has no difficulty passing stool or urine because he or she is naïve of any need to exercise control. By contrast, a five-year-old child is able to perceive the urge to eliminate, suppress the impulse to immediately void, disengage from play, find a bathroom, insure privacy, unfasten clothes, climb up onto the toilet, initiate passage of stool or urine, recognize when it is done, dismount, clean up, refasten clothes, unbolt the door, and emerge to successfully resume play [34]. This ordinary, taken-for-granted behavior is a result of perceptual-motor developmental skills that take months or years to develop [35, 36] They are acquired by two simultaneous processes: toilet training, what parents do to help their children towards socially appropriate, self-sufficient toileting; and toilet learning, what children think and do while learning the mores of eliminative behavior, recognition of sensory signals, and achieving control that enables them to choose to either void or retain urine or stool [37].

Beginning toilet training prior to 27 months of age does not benefit the child or the parent because it does not lead to earlier mastery of toileting skills [38]. Age-appropriate toileting is acquired through a process analogous to learning how to ride a two-wheeled bicycle. The parent can teach or “train” the child to ride by giving advice, assistance, and encouragement, but the parent cannot implant the skills of balance and locomotion in the child and the child cannot acquire the skills by passively receiving them. He or she has to learn them by repeated attempts at “getting it to work.” The attempts require a desire and ability to learn, courage, and the absence of emotional or cognitive problems severe enough to hinder the learning process.

Babies are born with instinctual sequences of behavior that are evoked by specific stimuli from their outer or inner environments, such as the neonate’s sucking response to an insertion of a finger into its mouth or the defecation response caused by contact of stool or a foreign body into the anus. These activities require no learning; they are present at birth.

With maturation and experience, motor activities become more and more purposeful. The newborn exists without a sense of separateness of its surroundings [39]. Development within the nurturing environment leads to the emergence of a sense of self and an awareness of the existence of others as separate centers of initiative. The older toddler and preschool aged child are inquisitive, but not able to think rationally. The psychiatrist and student of early childhood, David A. Freedman, wrote, “Typically, toddlers are not competent to understand why particular expectations or prohibitions are being imposed upon them… Most often a toddler can only know whether he or she ‘got it right’ after the fact, as a consequence of the effects of the behavior. For the toddler, who is just beginning to find his way as a separate center of initiative, this means learning to behave ‘correctly’ as defined by the strictures of parental authority. Often, ‘correctness’ is only known from the parents’ response to the child’s behavior. The youngster must, in this regard, always be playing catch-up” [40].

During the second and third years, parents place expectations on their child in activities such as toileting, self-feeding, and the ability to wait for help and attention. Normal parenting enables the child to strive to accomplish these goals. Each success entails the child’s pride of accomplishment. The infant’s tolerance and enjoyment of messiness is superseded by an increasing desire for order and cleanliness reinforced by admiration and approval from its parents. However, progress isn’t always easy. Incorrect behaviors that evoke parents’ disapproval threaten the child with perceived loss of the parent’s love, presence, or trust. Parents, for their part, assume responsibility for the success of their child in accomplishing self-control and they are vulnerable to feelings of anger, self-reproach, and guilt when their child-rearing efforts seem to fail. First-time parents may be more susceptible to self-doubt.

Parents’ regulation of their child’s eating, toileting, and sleeping is prone to difficulty. In contrast to the parents’ ability to foster social skills (e.g., consideration of playmates’ desires and rights) and safety practices (e.g., not running into traffic), attempts to regulate the child’s chewing and swallowing of food, the child sensing the urge to urinate or stool and exercising sphincter control, and getting a child to fall asleep—these are bodily functions which ultimately are entirely within the control of the child. For example, parents can oblige their child to sit at the table, but they cannot force their child eat; attempts to do so may result in oral defensive behaviors that may be too intense for the child to prevent, such as gagging or vomiting. Parents can oblige their child to sit on the toilet or force him to undergo an enema, but they cannot operate the child’s apparatus of retention and voiding. Noxious measures may succeed for the moment but they may increase the child’s fear of the defecatory urge and may intensify the withholding response to it. Parents can oblige their child to stay in his or her crib at bed time, but they cannot make the agitated toddler feel sleepy and lie down rather than standing up, holding on to the top of the side rail, fussing, or fighting sleep in some other way.

If conflict develops over eating, toileting or falling asleep, and if the preschooler who is in the process of acquiring autonomy and control resists parental guidance, and if his resistance brings punishment, he may respond with deepening obstinacy. A self-perpetuating impasse may develop with intensifying parental frustration and an increasingly anxious, noncompliant child.

Therefore, advising parents to somehow “make” their child eat, stool, or fall asleep may burden them with an impossible task, one likely to increase conflict between them and their child. No physician, parent, diet, or medication “cures” a functional disorder of defecation. Only the child can learn to overcome it. Optimal management consists of sensitive, empathic use of measures that facilitate the child’s efforts, such as orally administered stool softeners for children who have painful constipation, clarity regarding society’s expectations of individuals’ toileting practices, and avoidance of measures that heighten the child’s fears and stubbornness, such as coercive rectal interventions or attempts at imposing the parents’ dominance and their child’s submission regarding control over eliminative functions.

Clinical experience suggests that functional disorders of defecation are not so much a result of parents’ training methods, which are culturally diverse and seldom seem strange or abusive, but rather the result of difficulties the child experiences during toilet learning, such as how the child thinks about and copes with the threat of a painful bowel movement and the shame resulting from fecal soiling [37, 41].

Anxiety and Toilet Learning

Anxiety is an important factor in the pathogenesis of functional disorders of elimination, especially when it affects preschoolers. Three sources of anxiety are common: (1) fear of the dangerous stool within and the anticipation of pain should it come out (discussed below); (2) threats of coercion or humiliation and the retaliatory fantasies they engender; (3) environmental instability, especially perceived disturbances in parents’ wellbeing, such as a difficult pregnancy, post-partum depression, marital discord, moving to another house. An atmosphere of family disharmony results in tendencies for young children to be less concerned for others, more self-centered, less compliant, and more defiant [42–44]. It requires mental and emotional effort for a child to overcome a functional disorder of defecation and that effort can be disrupted by, for example, autism, attention deficit disorder, anxiety disorders, depression, or oppositional defiant disorder [45]. In any particular child, the difficulty of the therapeutic challenge in functional fecal retention syndrome, for example, is not the size of the retained fecal mass or the diameter of the mega-rectum that contains it. Rather, it is the psychological comorbidities that may be present [46]. Five-year follow-up studies in children with functional fecal retention syndrome revealed persistence of the disorder in 25–52 % of patients. The published rates of success or failure would be more meaningful were the factor of psychological comorbidity identified and elucidated [47–49].

Piaget’s Childhood Animism

The first of the above-mentioned three sources of anxiety (fear of the dangerous stool inside) merits further discussion. Piaget described the thinking of children under the age of 7 as animistic [39]. In other words, young children believe that inanimate objects are alive and capable of willful action. “Objects that provoke pain or fear are regarded as doing so from a conscious purpose because the self is still egocentric and in consequence is unable to give a disinterested or impersonal judgment.” As an example, a two-year-old might bump his head on a door knob and then react by “spanking” the door as though the hurt he experienced was caused by the door’s willful, hostile act.

E.J. Anthony recognized the relevance of childhood animism to toilet learning and the potential for stool withholding [34]. Toddlers and preschool children view their stools animistically; it is common for two-year-olds to wave “bye–bye” before flushing their toilet. One 3–5/12-year-old girl told me that, “the pooh–pooh doesn’t want to come out because it’s cold outside.” A 3–8/12-year-old boy, whose father routinely wiped him after bowel movements, asked his father to leave a bit of stool on the skin near his anus “to help the new poop come out.”

If a young child in the process of toilet learning has never experienced anal pain or frightening events related to defecation, he and his bowel movements “get along.” He does not feel threatened and learns control easily. By contrast, if a child passes a hard bowel movement that causes a minor anal fissure, he suddenly feels pain in part of his body he cannot see, associated with a bodily function he feels is not completely under his control. He cannot control it because “pooh–poohs” have a will of their own and are capable of being nice or nasty. And when one willfully hurts him, he becomes frightened by the defecatory urge and may respond by keeping the stool inside at all costs.

What are some of the implications of childhood animism for toilet training and the treatments of disorders of elimination? First, the style and method of toilet training aren’t nearly as important as whether or not they frighten the child and add to the anxiety associated with mastering control of fecal expulsion. Second, almost all normal children experience rectal intrusions, such as digital examinations or enemas, as hurtful and coercive. Unless it is critically important to perform a digital exam of a child’s rectum (e.g., to diagnose organic anal stenosis or pelvic appendicitis), then it is important to avoid intrusion into the anus of a resistant child, especially a child with a disorder of defecation or a child too young to understand the reasons for the procedure and incapable of cooperation. Third, when a child is afraid to pass stool because “it hurts,” the meaning of “hurts” encompasses more than physical pain. It includes the emotional distress of dealing with something he feels is a threat. Fourth, many children with functional fecal retention syndrome may persist in withholding stool even though they haven’t experienced a painful bowel movement in several weeks because of effective ongoing laxative administration. They continue to respond to the urge by withholding until the entirely soft content of the rectum is so voluminous it can no longer be withheld. It is persistent fear, not physical pain, that perpetuates this retentive behavior. The fear aspect of the problem as well as the mechanical aspect of the problem must be overcome for the disorder of defecation to end.

Pelvic Floor Motility: Coordinated, Uncoordinated, and Dyssynergic

The rectum, uterus, and bladder are all hollow pelvic viscera that communicate with the outside via conduits that pass through the pelvic floor. Resistance to flow through these conduits (anal canal, vagina, and urethra) is controlled by the tonus of the pubo-rectalis portion of the levator ani muscles. When contracted above the level of resting tension, this muscle simultaneously presses these conduits closed [50].

Normal defecation, micturition, and intromission during coitus require the relaxation of the pelvic floor below its level of resting tension. Normally, this relaxation is coordinated with expulsive pressure within the rectum or bladder or, in the case of female sexual intercourse, a state of psychophysiologic receptivity. The sense of bladder fullness which prompts a decision to urinate involves the cerebral cortex which, through a conscious act of will, releases inhibition of parasympathetic nerves to the detrusor muscle of the bladder causing it to contract, thereby increasing expulsive pressure. Normally, micturation results from detrusor contraction coordinated with adrenergically mediated relaxation of the smooth muscle of the internal urethral sphincter and somatically mediated relaxation of the striated muscle of the external urethral sphincter and pelvic floor [51].

Pelvic floor dyssynergia (PFD) [52–56] is defined as a pattern of persistent incoordination that interferes with normal emptying of the bladder or rectum but is not caused by any disease or lesion. PFD is central to the pathogenesis of stool withholding by children with functional fecal retention syndrome and those who go on to develop secondary urinary tract disease

How does PFD originate and become established? I had two experiences early in my career that prompted me to consider the effects of fear and anxiety on the motility of the pelvic floor. While interviewing the father of a six-year-old girl with massive fecal retention, I attempted to convey the idea that whenever his daughter felt the urge to stool, she anticipated anal pain and that this fear could prevent her from relaxing her bottom so that stool could pass. “Oh, you mean the pucker factor?” he asked. I asked him what that term meant. He explained that he had been a military pilot and that the “pucker factor” referred to a phenomenon that occurred en route home from combat missions. The moment the plane crossed into safe territory, crew members became aware of how tense their bottoms had become, which they then deliberately relaxed.

This prompted me to perform an experiment in which I placed a motion sensor on the anus of a volunteer subject without inserting anything into the anal canal, penetrating the skin, or causing physical discomfort of any kind. The sensor recorded the activity of the pelvic floor. The experimental subject was fully awake, comfortably supine and able to engage in conversation. The experiment reveled: (a) waxing and waning of pelvic floor tone at rest; [57, 58] (b) contraction of the pelvic floor above the level of resting tension whenever my tone of voice or behavior caused mild surprise or apprehension in the subject; and (c) these variations of pelvic floor activity occurred entirely out of the subject’s awareness. These findings supported the hypothesis that emotions influence pelvic floor motility and that this psychophysiologic effect occurred out of the subjects awareness. Fear increases anal sphincter pressure [59]. PFD is important when managing children with fecal retention; treatment methods should not be frightening and therefore less likely to exacerbate PFD [56]. Biofeedback therapy for PFD aims at bringing dyssynergic reflex activity that is out of awareness into awareness to enable the patient to learn how to make dyssynergic muscles function synergistically [60–62].

To summarize: there are at least five ways in which appropriate, synergistic relaxation of the pelvic floor can be impaired: (1) persistently painful lesions of the anus or perineum causing excessive contraction of the pelvic floor as a result of persistent activation of the cutaneo-anal contractile reflex; (2) the anticipation of pain caused by lesions that become painful during pelvic floor activity, such as an anal fissure that hurts during defecation; (3) anal, urethral or vaginal pain in the past that caused a learning experience that, in the present, inhibits synergistic relaxation of the pelvic floor during defecation, urination or coitus; for example, a child recovering from fecal retention syndrome who suffered severe anal pain during the passage of mega-stools in the recent past, may be frightened and have great difficulty relaxing his pelvic floor during defecation, even though currently effective stool softening would prevent physical discomfort; (4) fear and anxiety heighten skeletal muscle tone [63], including the pelvic floor, and fear of intrusion into one’s privacy during toileting may impair coordinated pelvic floor motility; (5) past experiences of combined physical and emotional trauma, such as rape involving vaginal or anal penetration, may result in a persistently dyssynergic pelvic floor [64, 65]. Vaginismus is functional spasm of the muscles surrounding the vagina resulting from a conditioned response to a previous real or imagined frightening sexual experience. It may be analogous to refractory fecal retention in children who have been sexually abused.

Hinman’s Syndrome

Hinman described a syndromic form of PFD in which functional fecal retention is accompanied by urinary retention and obstructive uropathy [52–54, 56, 66–68]. Prior to Hinman’s publication in 1973, it was generally thought that obstructive deformities of the urinary tracts in children with fecal retention were caused by crowding of the bladder within the pelvis by the impacted mega-rectum [69]. Therefore, if rectal constipation could seriously damage the urinary system, then serial enemas to remove the fecal mass seemed warranted.

Hinman conceived of a different pathogenesis and a different approach to management. He proposed that the voiding dysfunction was caused by dyssynergia of the bladder’s detrusor muscle and external urinary sphincter (i.e. pelvic floor). In retrospect, the abnormal radiologic findings described by Shopfner [69] (fecal impaction, anterior displacement of the urethra, hydronephrosis, vesico-ureteral reflux) are compatible with simultaneous obstruction of both bladder and rectum. Thus, fecal retention was not the cause of the obstructive changes in the urinary tract; rather, incomplete evacuation of stool accompanied by incomplete voiding of urine had a common cause, namely, the inappropriate anxiety- or fear-induced “uptight” pelvic floor [70–76].

Therefore, if it were important that treatments for functional fecal retention avoid exacerbating the child’s fear and anxiety, then it would be especially important to avoid frightening measures, e.g., serial enemas, in functional fecal retention complicated by obstructive uropathy.

Hinman’s Syndrome should be suspected in any child with functional fecal retention, particularly one who also wets during the day or night. The disorder can have its onset from early childhood to adolescence. Typical ultrasonographic findings are those of chronic proximal urethral obstruction: incomplete emptying of the bladder, bladder trabeculations, vesico-ureteral reflux, and dilatation of renal calyces in the absence of organic lesions that obstruct bladder outflow or neurologic disease. Incomplete emptying of the bladder predisposes to urinary tract infections [77], cysto-ureteral reflux and damaged renal function. As important as it is to keep the rectum clear of fecal impactions, it does not relieve incomplete bladder emptying; and as important as ureteral re-implantation may be for severe cysto-ureteral reflux in Hinman’s syndrome, such surgery won’t cure PFD or prevent the uretero-cystic valves from becoming incompetent again [78].

Children with Hinman’s Syndrome are chronically anxious [79]. The condition improves with effective psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic measures that lessen anxiety and decrease resistance to bladder emptying. Table 2.1 summarizes management of Hinman’s Syndrome.

Table 2.1

Management of Hinman’s syndrome

• Clear explanations to the parents regarding the physiology of the pelvic floor and the effects of stress-induced excessive contractility on the urethra and anal canal |

• Avoid enemas and suppositories |

• Biofeedback training (if practicable) to end the vicious cycle of detrusor-external urinary sphincter incoordination (a.k.a. dysfunctional voiding) [80] |

• Relieve the child’s worries concerning clinical encounters for this problem. “No poke, no pain,” free telephone access between visits for the child as well as the parents, and supportive follow-up visits until the problem has been overcome |

• Pharmacologic Measures: (a) lorazepam at bed time to lessen anxiety, deepen sleep, and relax the pelvic floor; (b) low dose doxazosin to enhance urine flow by blockading the alpha-1 adrenergic receptors of the internal urethral sphincter [83, 84]. (Reconsider use of this agent if incontinence worsens.) (c) Oxybutynin, 5 mg. b.i.d for overactive detrusor if there are symptoms of overactive detrusor associated with impaired bladder emptying; (d) surveillance for, and prompt treatment of urinary tract infections |

• Disimpaction of the rectum using an osmotic laxative that is acceptable to the patient, followed by ongoing routine use of osmotic laxatives to keep rectal contents soft enough to be passed without discomfort |

Philosophical Context of Clinical Management of Disorders of Elimination

Before proceeding to a descriptive classification of functional disorders of defecation, it is important to recognize that sincere clinicians have widely differing attitudes as to their role in these disorders. The various attitudes can be viewed on a spectrum, one end of which conforms to the biomedical model of practice which focuses on determining the presence or absence of organic disease, and the other end which conforms to the biopsychosocial model of practice which focuses on illness and all factors which may contribute to its development [85].

The following illustration contrasts the biomedical verses the biopsychosocial approaches using the commonest functional disorder of elimination, Functional Fecal Retention Syndrome (FFRS).

The purpose of the consultation in the biomedical model is to diagnose FFRS by recognizing its clinical features and excluding organic causes. A physician employing the biopsychosocial model is certainly responsible for not missing organic diseases, but goes further in attempting to elucidate the pathogenesis of each child’s stool withholding: how it came to be, as well as the strengths and weaknesses that the individual child and family bring to the task of recovery.

A biomedical view of FFRS is that it is disease-like, with the fecal mass equivalent to a foreign body that deforms the rectum, impairs rectal sensation, and promotes further retention. A biopsychosocial view is that the disorder is caused by a dysfunction having mechanical and emotional factors, i.e., the fecal mass and the child’s fear that it will cause pain and harm if it comes out.

If FFRS is analogous to an organic disease, then the key component of management, in the biomedical view, is removal of the foreign body-like fecal mass. This is typically done with enemas or intestinal lavage. Because the preferred clinical challenge is organic disease, and since most children with FFRS have none, the plethora of such patients in pediatric gastroenterology clinics is commonly viewed as clinical clutter. Following the initial consultation, management may be turned over to a nurse. A doctor isn’t necessary for treatment of an uncomplicated nondisease and his/her time is better utilized for patients with “real,” diseases [33].

By contrast, a biopsychosocial view is that the child has a functional disorder that, by definition, is not analogous to organic disease. Removal of the fecal mass is certainly important, but is best done by helping the child accomplish it for himself. Explaining the mechanics of fecal retention and bypass soiling helps the child comprehend what he needs to do. Avoidance of coercive measures that frighten him can be achieved with effective stool softeners to liquefy the fecal mass to the extent that it cannot be withheld. The physician develops parallel relationships with the child and the parents. The child is listened to. The essential mechanics of fecal soiling and laxative treatment are reiterated in terms the child can understand. The doctor empathizes with the child’s worries about passage of a bowel movement and attempts to reassure the child that, even though it might cause discomfort, it will not damage his/her body. The parents’ fears about physical harm must be elicited and relieved; they need to be reassured that their child is in no danger, even during “retentive crises” (see below). The physician continues to help parents avoid resorting to measures that might stress the child even further and impair his trust in them and his doctor. The knowledge that they can call the doctor during what feels like a crisis is enormously supportive.

With respect to functional disorders of elimination, the type of doctor–patient relationship that is typically utilized in the biomedical model is “guidance-cooperation,” to use the classification described by Szasz and Hollender [86, 87]. The type most useful in the biopsychosocial model is “mutual participation.”

Pediatric gastroenterologists have engaged in heated discussions over the necessity for digital examination of the rectum as part of the evaluation of patients with FFRS [88]. As stated by Doctors Ann Buchannan and Graham Clayden, “In children beyond infancy, it may be very distressing, especially when the constipation is likely to be related to anal pain. Little can be learned from a writhing child who is clenching every muscle to protect him/herself” [89]. “Children who have experienced coercive physical treatment for their constipation such as enemas or suppositories can produce symbols in drawings that are highly suggestive of violation or sexual assault” [89]. Inspection and palpation of the abdomen and inspection of the anus [90, 91] can obviate the need for a rectal examination in most cases.

In the biomedical model, the physician’s first concern is to rule out Hirschsprung’s disease and other pathologies; accomplishing that is more important than rapport with the child, especially if further treatment will be carried out by someone else. By contrast, in the biopsychosocial model, the physician’s first concern is to develop a trusting relationship with the child. The doctor tolerates the initial diagnostic uncertainty caused by not having done a rectal exam so that the child can feel that the doctor is his protective ally and can be trusted during the therapeutic process by which the child overcomes the disorder.

To sum up, until the day arrives when there are data that clearly support the superiority of either the biomedical or biopsychosocial models with respect to functional disorders of defecation, it behooves us to acknowledge that these differences exist.

Diagnostic Techniques in the Diagnosis of Disorders of Defecation (Historical, Physical, and Radiologic)

Diagnosis of the various kinds of disorders of defecation is based upon the presence or absence of three phenomena: Soiling, fecal retention, and organic disease. Historical, physical, and radiologic findings can be misleading. Therefore, each diagnostic tool warrants more precise definition.

Objective evidences of soiling consist of deposits of stool in underwear greater than a smudge (that could be caused by passage of flatus or incomplete wiping after a normal bowel movement) and persistent fecal odor. Because its receptors for touch, temperature, and friction may fail to signal presence of liquids at body temperature, the anoderm can be “fooled” by a small amount of liquid stool, mucus, or oil. Imminent leakage isn’t sensed quickly enough and soiling occurs largely out of the individual’s control. Such soilage is not necessarily abnormal, indicative of diarrhea, “bypass” soiling around the fecal mass, or sensory deficits of the anoderm [91].

Persistent stool withholding results in a mid-line mass palpable trans-abdominally behind and above the public symphysis. After weeks or months of retention, the mass grows upward to the level of the umbilicus and, with further enlargement, can extend to the costal margin. The rectal accumulation causes a mega-rectum which fills the true pelvis and enlarges upward [25], but progressive accumulation of stool does not fill and distend the more proximal colon in patients with FFRS (Fig. 2.3).

Fig. 2.3

An enormous megarectum in a 13-year-old boy with FFRS who could not recall defecating during the preceding year. Notice the scybalous stools in the nondilated colon orad to the recto-sigmoid

The presence of fecal retention can be assessed by abdominal palpation, digital rectal exam, or radiography [92]. The extent of rectal enlargement can be determined by a radiograph of the pelvis. The recto-pelvic ratio (RPR) is the diameter of the rectum divided by the maximum transverse diameter of the pelvic outlet. A RPR above 0.61 is characteristic of a mega-rectum [92].

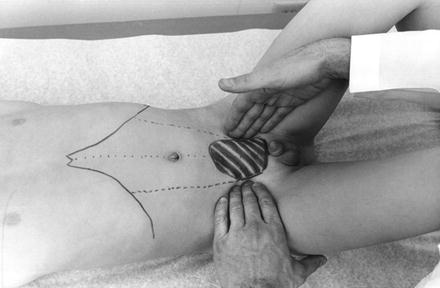

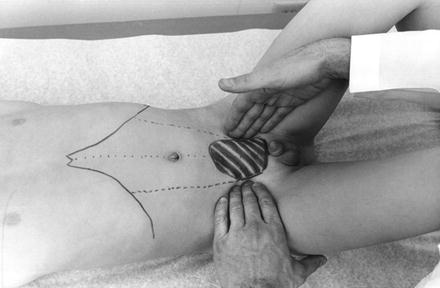

Abdominal palpation is least intrusive and does not expose the child to radiation. It is best done with the patient supine, knees drawn up, and abdominal muscles relaxed (Fig. 2.4).

Fig. 2.4

Physical examination for the presence and extent of fecal retention by abdominal palpation. The fecal mass is ballottable with the finger tips of the right hand being the “pusher” and those of the left hand, the “sensor”

It is difficult to palpate abdominal masses through the rectus abdominis muscles. Therefore, place the finger tips of one hand just to the left, and the fingertips of the other hand to the right of the rectus muscles. The finger tips on one hand are the “pusher” and those of the other are the “sensor.” A fecal accumulation can thus be balloted as a firm, movable, nontender mass in the midline, extending upward from deep within the pelvis anterior to the sacrum. (Some children have a prominent fifth lumbar vertebra that might be mistaken for a midline mass, but it is not movable and does not extend down into the pelvis.)

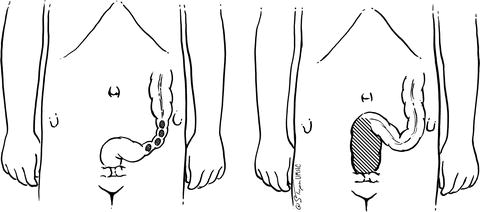

In contrast to the midline mass of intra-rectal stool that accumulates as a result of functional or organic rectal outlet obstruction, the typical finding in Irritable Bowel Syndrome constipation consists of lumps within the distal descending and sigmoid colon palpable in the left iliac fossa. This results from heightened segmenting motility of the sigmoid colon, not from fecal retention within the rectum (Fig. 2.5). Of course, both midline and left iliac fossa findings may coexist. The stools of IBS constipation may scratch or fissure the anoderm during defecation and thereby predispose to functional stool withholding in vulnerable children. However, blurring the distinction between “pellet stool constipation” and “stool withholding constipation” is not helpful, if for no other reason than increased fiber intake helps the former but does nothing for the latter.

Fig. 2.5

Typical palpatory findings in constipation-predominant IBS (left) and rectal constipation (right)

It may be difficult to be sure of the presence of a fecal mass that has been recently passed or softened to the extent that it is no longer palpable. Or, the child’s soiling may be of the nonretentive type [93]. In such cases, the response to a few days of osmotic laxative in doses sufficient to liquefy a hard fecal mass will aid diagnosis. If massive amounts of stool are passed, followed by improved mood and appetite and cessation of soiling, then it is reasonable to assume that the child’s soiling was due to functional fecal retention and management can proceed expectantly based on that assumption.

Digital examination is warranted when Hirschsprung’s Disease is a clear possibility. A narrow anal canal and an empty lower rectum in a child with a palpable fecal mass in the abdomen and/or chronic abdominal distention suggests Hirschsprung’s disease or other organic motility disorder. A limited contrast enema, without prior “clean out,” using a water-soluble contrast medium is warranted if Hirschsprung’s disease is a clear possibility.

Abdominal radiographs should not be used routinely to assess fecal retention because of radiation exposure and the efficacy of the interval history, abdominal palpation, and inspection of the anus for soilage. However, accurate palpation may not be possible through the panniculus of an obese child. In such cases, one radiograph that includes the perineum and entire abdomen is useful to document the diameter of the rectum, whether or not a mega-rectum fills the true pelvis and extends all the way down to the pelvic floor, the extent to which it occupies the abdominal cavity [25], and whether or not there are defects in the sacrum suggestive of neuropathic fecal incontinence.

Functional Disorders of Defecation Syndromes

A retrospective review of 395 randomly selected charts of children seen by me with problems of defecation revealed seven syndromic patterns (Fig. 2.6): Functional Fecal Retention Syndrome (FFRS), which I have sub-categorized into established and emerging types; Functional Nonretentive Fecal Soiling (FNRFS) [93]; children who had features of both functional retentive and functional nonretentive fecal soiling at various times in their history; children 3–6 years of age with age-inappropriate use of diapers, “diaper dependency” (a.k.a. “stool toileting refusal”), which can be sub-grouped as essentially “permitted” vs. “contentious”; and seven patients in the “miscellaneous” group, which included one child with the Infant Dyschezia Syndrome; the remaining six presented with complaints that I could not categorize as conforming to a recognizable pattern or syndrome. What follows is the discussion of the features of each category and concepts of management.

Fig. 2.6

Functional disorders of defecation in 395 pediatric patients: Seven syndromic patterns

The Functional Fecal Retention Syndromes (FFRS)

Painful bowel movements due to, for example, an anal fissure, may cause a child to feel alarm when he or she experiences the urge to defecate. He responds by tightening his pelvic floor to prevent passage of stool until the urge subsides (Fig. 2.7). He has lost, or perhaps never fully mastered, the ability to easily relieve himself of the defecatory urge. Feces accumulate and harden within the rectum and may either be passed with great distress or retained for weeks or months at a time [95, 96].

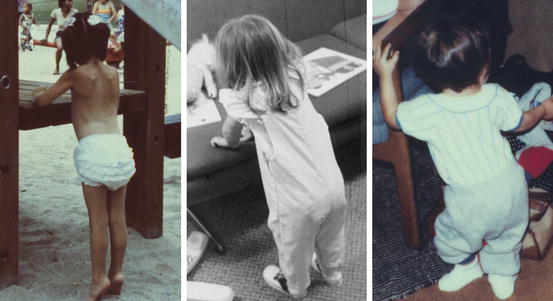

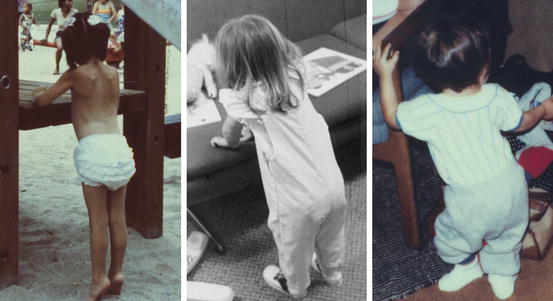

Withholding in response to the defecatory urge may begin in infancy or later childhood. In its early phase, the predominant behavior may consist of straining at stool and may result in passages of stool as large as a tennis ball or a soda can. However, as the intra-rectal fecal mass enlarges, it becomes virtually impassable. Memorable experiences of anal pain and the normal animistic view of the fecal lump that hurts results in fewer efforts at evacuation. Retentive posturing [91] becomes more apparent. It consists of tightening, rather than relaxing, the pelvic floor and tightening of the gluteal muscles and thighs (Fig. 2.8). These actions reinforce the withholding action of the fatiguing pelvic floor. A young child may seclude himself behind furniture or in his room as he is fighting the urge to stool. This behavior may be a desperate attempt to secure privacy and avoid the attention of his parents who may become alarmed, intrude and give advice he doesn’t want. Retentive posturing may consist of “heel-sitting,” by which a child may stop to “tie his shoes” and, in the process, occlude his anus by sitting on his heel. Or, the child may stiffen and cross his legs while standing, holding onto furniture to steady himself, or lying prone with his lower limbs held straight and stiff [97].

Fig. 2.8

Three examples of retentive posturing: tightening of the buttocks to reinforce maximal contraction of the pelvic floor in response to the urge to stool

Increasing retention causes the full clinical picture to emerge [9, 98] (Table 2.2). Fecal masses become palpable in the abdomen. The patient experiences abdominal discomfort and becomes less interested in eating. He is irritable and less playful. “Bypass” or “overflow” soiling may be mistaken for diarrhea [99]. Retentive posturing recurs several times a day. After days or weeks, a retentive crisis may occur during which the urge to stool becomes overwhelming, causing not only physical distress, but panicky, pain-like behaviors. Typically, parents become alarmed and may rush the child to an emergency room fearing an imminent intestinal catastrophe. A gigantic stool that may be too large to flush is finally passed. Success in passing the mega–stool is promptly followed by a dramatic change in behavior. What appeared to be an acute emergency just minutes before changes to relief and composure followed by the return of the child’s appetite and playfulness.

Table 2.2

Clinical features of the functional fecal retention syndrome in children

• Passage of enormous stools at intervals of one or more weeks |

• Obstruction of the toilet by such stools |

• Indications of increasing fecal accumulation: Retentive posturing Soiling Irritability and decreased playfulness Abdominal discomfort or pain Decreased appetite |

• Dramatic disappearance of these symptoms after evacuation of enormous stools |

• Behaviors indicative of patients’ irrational efforts at coping with soiling: Apparent nonchalant attitude regarding soiling Alleged lack of awareness of soilage Hiding of soiled underclothes |

The child probably experienced the retentive crisis as something horrible. Nevertheless, children’s nonrational thinking prompts a withholding response the next time they feel the urge to stool and the cycle typically repeats itself over the course of a week or more. In time, the child becomes overwhelmed by a loss of control. He may attempt to cope with the problem by making believe it doesn’t exist. He may seem unaware or unconcerned about soiling, which frustrates his parents and causes them to suspect a neuropathic loss of the child’s ability to feel the urge to stool.

The child’s apparent nonchalance contrasts with his desperate attempts to conceal his problem. He may clumsily hide his soiled underwear in inappropriate places, such as the floor of his closet, in his underwear drawer, behind his clean clothes or under his bed. (One child put them in his sister’s guitar. Another hid them in the living room under the lid of the piano stool.) The child’s soiling, refusal to use the toilet for bowel movements, and his seeming lack of concern vex his family. Of all the accidents that might trouble the child, fecal soiling evokes the most intense deprecation from peers and parents and damage to self-esteem [34, 100].

Emerging Functional Fecal Retention Syndrome

Emerging FFRS is presented to emphasize the importance of prompt and effective treatment of constipation in infants and toddlers, before their initial responses to the urge to stool change from predominantly expulsive to predominantly retentive.

Case Vignettes

Case 1: A first-born five-month-old boy passed meconium within the first 24 h of life. He was breastfed for 3 months, during which he passed one mushy stool per day. At 3 months, the patient and his parents visited relatives in a foreign country. The patient did not defecate for 4 days and became irritable during the third week of their trip. A teaspoon of mineral oil was followed, an hour later, by the distressful passage of a firm, wide, blood-streaked stool. He was then given prune juice every day, but again failed to stool for 4 days. He then passed a soft-formed, nonbloody stool with much effort. At 4 months of age the family again traveled out of the country to visit relatives. They returned home 9 days later. Prune juice was discontinued out of concern that the infant might become “dependent” on it. The patient continued to stool every 4 or 5 days and did so lying on his back with knees extended, buttocks tense, back arched (a retentive posture), and face flushed). Physical exam revealed a robust, socially responsive infant. His abdomen was soft; there was no palpable mass of retained stool. The anus and spine were normal to inspection. The physical exam was otherwise negative. Management included avoidance of rectal intervention and prompt, gentle wiping with a lotion that would not sting if applied to fissured skin, using a soft tissue or cotton ball. The perianal skin was protected with heavy applications of a bland barrier ointment. Stools were kept soft, but not runny, with orally administered lactulose and mineral oil in increasing doses, depending on the number of days he had gone without a bowel movement.

Case 2: A first-born, three-month-old girl was the product of a normal pregnancy and delivery. She was fed cow’s milk formula and passed unformed stool 6–7 times a day. Her perianal skin became irritated. At 1 month, bowel movements were preceded by 20–30 min of inconsolable crying during which she stiffened her body with her legs extended, arms flexed, and “face beet red.” This culminated in a passage of a pasty or loose stool after which her distress resolved within a few minutes. Blood was present on cleansing tissues after some of her bowel movements. Applications of an anti-mycotic steroid cream and digital exams of the rectum failed to relieve her symptoms. Physical examination revealed a healthy-appearing infant. Abdominal palpation was negative, as was the rest of the examination, except for the anus, which had a small tag with an adjacent fissure which oozed blood. Management included avoidance of rectal intervention, maintenance stool softeners, comfortable wiping after bowel movements and ongoing protection of the perianal skin with a bland barrier ointment.

Comment

Both of these infants’ symptoms were prodromal to FFRS. Why should infants only a few months old develop symptoms of emergent functional fecal retention? If a month-old baby experiences anal or perianal pain associated with defecation, the ease with which the infant defecates may be lost. Put in terms of classical conditioning theory, the defecatory urge is a neutral stimulus which induces a reflex response,i.e., passage of a comfortable bowel movement. If anal pain accompanies reflex defecation, the defecatory urge becomes a conditioned stimulus which triggers the conditioned response of emotional distress plus nocicepetive reflex contraction of the pelvic floor and other muscular activities that constitute a withholding response. Management of fecal retention, in terms of behavioral psychology, amounts to extinction of the fear/withholding response. This is accomplished over time during which the causes of anal pain are removed by making stools consistently soft and allowing the abraded or fissured anoderm and perianal skin to heal. In addition, noxious stimuli, such as anal dilatation, suppositories, enemas, or thermometers are avoided. The conditioned stimulus (i.e., the defecatory urge) in time reverts to a neutral stimulus as reflex bowel movements are invariably pain free and the conditioned response (distress and withholding) is extinguished.

Management of Functional Fecal Retention Syndrome

What Do Parents Need?

After discovering what the parents have been previously told and their concerns about their child’s soiling and inability to defecate comfortably, I begin with “de-mystification” to address their cognitive needs [101]. This consists of a didactic description of the functional anatomy of the apparatus of defecation and fecal continence. For the purposes of orientation, I begin with a diagram of the GI tract, describe its basic functions, and then focus on the colo-rectum and pelvic floor. I describe the normal sequence of activities as stool enters the rectum, causes the urge to defecate, is withheld, and passed. Using a diagram, I describe how a mega-stool develops and how it effaces the anal canal, thereby preventing the pelvic floor muscles from operating as a sphincter. I explain how their child’s report of “not being able to feel it come out” can be attributed to the inability of the anoderm to sense contact by fluids at body temperature, a normal rather than a pathologic phenomenon.

The focus then shifts to unrealistic worries about fecal retention. Parents often worry unnecessarily that retained stool may accumulate throughout the length of the intestine (instead of mostly in the enlarging rectum [25]) and that it poses the threat of toxic contamination to the entire intestinal tract. Other common worries are that the colon might burst or that the mega-rectum is permanently damaged and may never return to its normal size and function. Parents are usually amazed to hear that children with FFRS have safely gone for months without bowel movements during which nothing passes except seepage. Intestinal perforation rarely, if ever, occurs in otherwise healthy children who withhold stool (even those who have retained stool for so long that their parents cannot remember when their child last passed a bowel movement) and a fecal mass that is palpable up to the costal margin. An analogy with the uterus, another smooth muscle viscus, may be useful for purposes of reassurance; the uterus expands to accommodate its contents and returns over time to normal size after its contents have been delivered. Clinically significant small bowel bacterial overgrowth is not a feature of chronic stool withholding in otherwise healthy children. As uncomfortable as fecal retention may be, it poses little danger, except for those children with pelvic floor dyssynergia (discussed above) and girls with recurrent urinary tract infections due to the ascent of bacteria from a chronically soiled perineum.

Parents are also burdened by the notion that their child’s toileting skills are mostly created by their efforts at toilet training, with little consideration given to the child’s toilet learning process. They may doubt their competence as parents. They also suffer embarrassment caused by their child’s soiling in school and in public. Their embarrassment is reality-based. The emotional strain on the child and his family may result in angry and perhaps abusive interactions. Nevertheless, a punitive reaction by parents may lessen the child’s willingness to do the many little acts of courage necessary for recovery, such as taking medication or making efforts to relax his pelvic floor during defecation or doing so on the toilet rather than in his underwear while hiding.

Since laxatives are a mainstay of management, parents need some understanding of how they work. The safety of long-term administration of osmotic laxative needs to be contrasted with the routine use of detergent or stimulant cathartics [102]. Whereas long term daily use of stimulant laxatives may induce tolerance (which can be misinterpreted as unwanted habituation and dependency), osmotic laxatives such as polyethylene glycol do not [103]. They may prefer feeding their child a high fiber diet as a healthier means of achieving laxation. Many dietary measures are harmless [104], provided they don’t cause conflict with their child around eating. However, they are ineffective in melting-down an established hard fecal mass within the rectum; water is required for that and the easiest way to bring water into the rectum is with an orally administered osmotic laxative, such as polyethylene glycol.

Parents are helped to react to their child’s toileting problems with less frustration if they see his difficulty in terms of his sense of desperation and loss of control. Lecturing a child with fecal retention on the reasonableness of his passing of bowel movement will not relieve his fear. Helping parents empathize with their child helps them become less anger-prone and better able to facilitate progress [105].

Parents may harbor fears that have little or no scientific basis and should be assuaged. Although bouts of abdominal cramping may become severe, even to the extent of causing reflex vomiting on rare occasions, colonic obstruction of a surgical nature almost never occurs, regardless of how much stool has accumulated, provided that there is no organic disorder such as aganglionosis or intestinal pseudo-obstruction. A dilated rectum does not prevent effective defecation, provided the contained stool is liquefied or at least softened to a pasty consistency. The main impediment to the passage of soft stool is inappropriate contraction of the pelvic floor, not failure of sensation or motility of the stretched rectal wall.

How much laxative is needed depends on how soft stools have become. The best indication of stool softness is its diameter when passed. Spherical or columnar stools wider than about an inch are too firm. If stool is soft enough, through and through, it will be extruded with a diameter that will not stretch the anus to a painful extent. Regardless of how soft stools appear on their surfaces, stools wider than normal may cause anal pain when passed [106].

What Does the Child Need?

Let it be said that no doctor, medication, or parent “cures” FFRS. The cure can be accomplished only by the child, the only person in control of his or her body. The physician, parents, school teacher, and other caregivers function as helpers to the child [107]. They cannot “fix” the problem without the child’s motivation and initiative. Although behavioristic concepts of positive and negative reinforcements have value, it should be born in mind that overcoming constipation and soiling is its own best reward. Bribes or punishments may not produce sustained improvement. The offer of a bribe changes the incentive to stay clean from something done to get rid of a problem that damages self-esteem, to something done to acquire a reward. Sooner or later, there may be demands for bigger rewards. The “positive reinforcement” may stop working as the parents become resentful and feel that they are being taken advantage of.

Parents’ concern that their child will suffer humiliation may prompt extraordinary measures to shield their child from such painful experiences. To what extent should their child be protected from the humiliation caused by soiling? The danger is reality-based. Deprecation by peers and others who do not owe the child parental love is the consequence of the child’s actions and, as such, may help motivate the child to try to get rid of the problem. An important difference between suffering the consequences of one’s behavior and being punished for the behavior is that the former may be painful, but it does not engender a desire to retaliate the way punishment does. Too often, the effect of punishment is to lessen the child’s motivation to work on his problem; his motivation shifts from feeling bad about his problem to feeling angry towards those who punish him. It is more helpful for the child’s caregivers to sympathetically validate the social dangers of soiling and the inescapable fact that family members and friends tend to react to someone who soils with rejection and avoidance. It should be made clear to the child that, in contrast to his attempts to solve the problem of embarrassment by making believe it doesn’t exist, others cannot go along with this “solution.” Instead, they react as though fecal soiling is an offensive act. Caregivers’ sympathetic but forthright tone serves to get their point across without sounding punitive, thereby maintaining their role as concerned helpers. They should not attempt to ease their child’s embarrassment and self-reproach by minimizing how offensive fecal soiling actually is.

Because, ultimately, the child is the agent of recovery, success in management of FFRS requires an understanding of the child’s point of view. The child’s animistic concept of feces and defecation are of central importance [34]. Children typically fear the “dangerous” stool inside of them. For example, one patient told me that his bowel movement is “a poisonous snake that bites me when it comes out.” Another said, “It’s an alligator.” Another described his stools as “a house” (with sharp gables and steeples). The magical thinking used to cope with such threats is exemplified by the following: “If I can keep it from coming out, then it won’t hurt me.” Another said that he holds it back “until it goes away,” i.e., until the urge subsides. One seven-year-old girl, the child of a socially prominent family, was remarkably articulate, pretty, poised, and tastefully dressed, but she had a fecal mass that extended above her umbilicus as well as an inescapable malodor. In our private chat, I asked her when she last passed a bowel movement. “Oh doctor!” she replied, “I don’t do that any more!” To her way of thinking, her problem had been solved.

Management is based upon gaining an understanding of the pathogenic factors in each case. Although childhood animism is a key factor in the pathogenesis of FFRS, there are other factors to be sought and considered. One of them is the child’s constitutional stool pattern. Some individuals defecate at regular intervals or times of day; others are “irregular” and defecate sporadically [108]. The notion that “irregularity” is not as healthy as a regular pattern of bowel movements is untrue and may cause unnecessary pressure on the child to defecate at times she does not feel the urge to stool because there is no stool in the lower rectum. This may cause performance anxiety or conflict that gets in the way of easy defecation.

A child with heightened segmenting motility in the sigmoid colon may produce firm, lumpy stools at irregular intervals, as is typical of constipation-predominant IBS. Scyballous stools, singularly or in agglutinated lumps, may abrade or fissure the anoderm. The resultant dyschezia may prompt a withholding response caused by anticipated pain. This is common in infants and young children with emerging FFRS.

Temperament refers to stylistic characteristics which are evident in infancy and later on. Infants’ temperaments differ. Some children are characterized by regularity, positive approaches and responses to new stimuli, high adaptability to change, and mild or moderately intense mood which is predominantly positive. At the other end of the spectrum are infants characterized by irregularity in biological functions, negative withdrawal responses to new stimuli, poor adaptability to change, and intense mood expressions which are frequently negative [109]. Parents may interpret fussiness of a temperamentally more irritable infant as physical discomfort caused by the need for a bowel movement. They may then resort to a suppository or enema. Any subsequent quieting may be taken to mean that the infant needed such intervention which, therefore, is more readily administered the next time the baby fusses. A vicious cycle may become established leading to the perpetuation of stooling difficulties in infants and toddlers.

Children with neurodevelopmental problems may have more difficulty mastering toileting skills. Any condition that interferes with the child’s ability to focus attention and effort may impair recovery. Functional disorders of elimination may be comorbidities of attention deficit disorder or autism [110, 111]. Spastic cerebral palsy may interfere with coordination of abdominal and pelvic floor actions that facilitate defecation. Anticholinergic medications harden stools.

Excitement, vacations, or emotional distress within the family are often important when progress is interrupted or regression occurs. The dilution of parental attention when a new baby is brought home may cause a regression in a young child’s toileting. A not infrequent problem arises when the child of separated parents spends part of the week with one parent, the rest of the week with the other and the parents have conflicting attitudes about their child’s disorder and the prescribed treatment regimen.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree