Features of functional dyspepsia

Persistent or recurrent epigastric pain or discomfort occurring at least once a week for the past 2 months

Pain or discomfort that is not relieved by defecation or associated with a change in bowel pattern (i.e. not suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome)

No structural or metabolic abnormalities that can explain the symptoms

Pain interferes with normal activities

Consider

disease

Peptic ulcer disease (night-time waking)

Helicobacter pylori infection

Constipation

Viral illness (dyspeptic symptoms may follow a viral illness)

Constipation should be excluded as a potential cause of functional dyspepsia as severe constipation with extensive faecal loading can present as epigastric discomfort/bloating.

Dyspeptic symptoms can follow viral infections particularly if prolonged and severe, for example Epstein-Barr infection.

Abdominal Pain Associated with Altered Bowel Habit (Irritable Bowel Syndrome)

IBS is common in childhood and adolescence and affects up to 10–20 % of adolescents, and it is similar to the adult presentation [10]. The typical features include abdominal discomfort or pain with two of three additional features; pain relieved with defecation, onset of pain associated with a change in form or frequency of stool (Table 19.2). Other supportive symptoms include—abnormal stool frequency or type, passage of mucus and bloating/distension. There is no evidence of an underlying organic disorder to explain the symptoms. There may well be a description of exacerbation of symptoms with stressors (physical/psychological), for example with exams/performances. IBS can coexist with organic disease and is common in conditions such as inflammatory colitis. A family history of IBS is common and can help parents understand their child’s symptomatology and help with reassurance and explanation that there is no serious underlying organic disease.

Table 19.2

Irritable bowel syndrome in children

Features of irritable bowel syndrome in children |

Abdominal discomfort or pain occurring at least once a week for the past 2 months, that has two out of three associated features occurring more than 25 % of the time: |

Onset associated with a change in form of stool |

Onset associated with a change in stool frequency |

Relieved with defecation |

No structural or metabolic abnormalities that can explain the symptoms |

Pain interferes with normal activities |

Consider/exclude |

Constipation or overflow |

Incomplete rectal evacuation |

Infection (especially if history of travel) |

Care should be taken in asking families about change in stool frequency/form. A total of 118 children, aged 7–10 years, with RAP , were surveyed to compare parental and children’s symptom recall to symptom diaries over a 2-week period, and also to the Rome III description of IBS. There was relatively poor correlation between symptom diaries and parental symptom recall, and the authors speculated that when completing questionnaires asking about pain–stool relations, parents compared their child’s symptoms to perceived norms of pain and stooling, rather than looking at their child’s symptoms over at least 25 % of the time. Children often had difficulty putting their symptoms into a pattern, so had difficulty recognizing their symptoms as IBS. Parents sometimes did not recognize their recorded symptoms as suggestive of IBS, due to recall bias, and infrequent events affected their interpretation of their child’s symptoms; symptom diaries can improve parental understanding and acceptance [9] .

Abdominal Migraine

It is important to recognize this phenotype. Abdominal migraine is a distinct clinical entity, distinguished by paroxysmal episodes of intense, acute peri-umbilical pain that lasts for one or more hours. These painful episodes can be associated with nausea and vomiting, pallor, headache, anorexia, and photophobia (Table 19.3). It is characteristic of migraine that the child is completely well between episodes. It is important to recognize that children may have cyclic vomiting as the main manifestation. Cyclic vomiting syndrome plus refers to cyclic vomiting in children with underlying neurological problems .

Table 19.3

Abdominal migraine in children

Features of abdominal migraine in children |

Paroxysmal episodes of intense, acute, peri-umbilical pain lasting for more than 1 h; occurring more than twice in the preceding 12 months |

Pain interferes with normal activities |

Intervening periods of normal health |

Pain is associated with two or more of the following |

Anorexia |

Nausea |

Headache |

Vomiting |

Photophobia |

Pallor |

No structural or metabolic abnormalities that can explain the symptoms |

Consider |

Cyclic vomiting syndrome (plus)- part of the migraine spectrum |

There are potential specific treatments for abdominal migraine/cyclic vomiting, as discussed below.

It is likely that abdominal migraine , cyclic vomiting syndrome and migraine headache are different clinical presentations of the same disorder along a disease spectrum. Many patients have a history of travel sickness. Dietary triggers include caffeine-, nitrite- and amine-containing foods. The diagnosis of abdominal migraine is supported by a positive family history of migraine headache.

Isolated Paroxysmal Abdominal Pain (FAP, FAP Syndrome)

FAP encompasses episodic or continuous abdominal pain in a school-aged child , with insufficient criteria for other functional GI disorders as described above (Table 19.4). There is generally no relationship with physiological events (e.g. eating/defecation), and pain is localized to the umbilicus. There is at least some loss of daily functioning, and the pain is not feigned. There is no structural/metabolic abnormality that would explain the abdominal pain.

Table 19.4

Functional abdominal pain

Features of functional abdominal pain |

Persistent or recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort occurring at least once a week for the past 2 months |

Pain or discomfort that is not relieved by defecation (i.e. not suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome) and not associated with eating |

Pain interferes with normal activities |

No structural or metabolic abnormalities that can explain the symptoms |

Consider |

Coexisting symptoms (fatigue, headache, limb pain) |

Coeliac disease |

Peptic ulcer disease (night-time waking) |

Helicobacter pylori infection (especially if history of travel) |

Constipation |

Viral illness (dyspeptic symptoms may follow a viral illness) |

Inflammatory bowel disease (blood in stools, night-time defecation) |

Pancreatitis |

Hepatobiliary disease |

Gynaecological disorders, for example polycystic ovaries/dysmenorrhoea |

Anatomical abnormalities, for example Meckel’s diverticulum/malrotation |

Food allergy/intolerance (specific dietary triggers, history of atopy) |

Functional abdominal pain syndrome refers to the above, occurring > 25 % of the time, with additional somatic symptoms, for example headache, limb pain, sleep disturbance and chronic fatigue and hence the term syndrome. This group tends to be more complex to treat and to do less well. The presence of features such as limb pain and chronic fatigue can be predictive of symptom perseverance [11, 12].

FAP can coexist with organic disease and like other functional GI disorders can occur in children with significant organic disease such as cystic fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [13]. It is important that parents become aware of this, and that clinicians are aware and avoid overtreatment and that such factors are considered in the assessment of children with serious underlying chronic disorders.

The group of children with FAP syndrome is often the most difficult to manage.

In summary

Recurrent abdominal pain is common

Presentation to the medical profession reflects impact on functioning

Classification by functional subgroup can be helpful, using Rome III criteria

FAP syndrome highlights the impact of symptoms, the coexistence of other functional symptoms and its complexity

Underlying organic disease can coexist

The etiopathogenesis is discussed in the next section

Etiology of Recurrent Abdominal Pain

Understanding the etiopathogenesis is essential, to provide parents with a clear explanation, that they can understand, and that helps address their concerns . Recurrent (functional) abdominal pain appears to be a variable combination of genetic predisposition, personality, visceral hypersensitivity and considering predisposing triggers (physical and psychological) is key. The acceptance of the biopsychosocial model by the patients and their families is an important factor in predicting a positive outcome and can help address some of the family’s understanding of the role of pain and coexistence with anxiety.

Pain Syndromes in Childhood: Historical Perspective and the Modern Integration with Stressors

Historically, the manifestation of stressors as symptoms has long been familiar to doctors. Just as recurrent functional headaches have historically been a common presentation to neurologists, and recurrent limb pains to rheumatology, so one of the earliest descriptions of FAP , with its association with stress was outlined by Moro in 1913—with increased likelihood in ‘sensitive’ children [14]. Apley (1958) assessed 1000 children in Bristol having annual school medicals, and found a prevalence of abdominal pain in more than 10 %; with worry or excitement as obvious trigger factors, and noted a higher incidence of anxiety, and timidity in the affected children, and higher incidence of functional symptoms such as headache and RAP in the affected children’s parents [1]. Few have significantly enhanced these seminal observations. In 1967, Green highlighted similar physical and psychological trigger factors and cautioned against the need for excessive investigation [15].

One cohort of children (6–19 years) in Denmark was followed up annually for 8 years (2168 children) [11]. On assessing for abdominal pain, headache and limb pain, it was noted that the prevalence of abdominal pain at baseline was 12.3 % (peaking at age 9 years and then falling through adolescence) , headache prevalence was 20.6 % (peaking at age 12 years and falling through adolescence) and the prevalence of growing pains was 15.5 % (remaining constant until age 11 years, but in girls peak age was 16–17 years). At least one third of children still had symptoms after 8 years of follow-up. He noted the association with stressors such as ‘broken homes’ and noted the higher incidence of parental symptoms such as headache or RAP . This leads onto the discussion of the impact of stress factors.

Role of Stress Factors

Stress is a considerable component of RAP , and each patient’s stressors is often a unique combination of the factors outlined in this following section. Helping parents to understand the impact of stressors on the child’s symptoms, in either causation or perseveration, and how the inherent personality of the child reacts to these external stressors remains key to determining a positive recovery.

The different triggers are outlined in this section and summarized in Table 19.5, and trying to elicit the triggers that are important to the child requires building a rapport with the child during the consultation. Merely relying on parental interpretation may miss some of these key triggers, and techniques such as ‘the three-wishes strategy’ may be useful in younger children .

Table 19.5

Potential stresses in children with recurrent abdominal pain

Potential stresses in children with recurrent abdominal pain | |

|---|---|

Physical | Psychological |

Recent physical illness | Poverty |

Postviral infection/postviral gastroparesis | Death of a family member |

Food Intolerance—poor diet, wheat, carbohydrate intolerance, excess sorbitol | Separation of a family member—divorce, child going to college |

Different and/or multiple medications, for example NSAIDs, antispasmodics | Altered peer relationships |

Constipation | School issue |

Chronic illness | Illness in parents or sibling |

Lack of exercise | Geographical move |

The ‘three-wishes’ strategy, as an outline, offers younger children three wishes to help them change their lives or taking away things they find difficult [16]. This technique can help younger children to outline some of their triggers of anxiety.

Personality Type and Family Factors

Early life factors can be important, with genetic and environmental factors evident. Familial studies of IBS have demonstrated that reporting a first-degree relative with abdominal pain or bowel problems is significantly associated with reporting of IBS symptoms [17]. Also, a study of Australian twins and the larger US study showed that the concordance rate for IBS between mono-zygotic twins was significantly higher than that between dizygotic twins [18]. In these children with functional symptoms, one study identified 23.7 % of parents having functional symptoms themselves [6].

In general, children with functional symptoms tend to be rather timid, nervous/anxious characters. They are often perfectionists—overachievers with increased number of stresses and who are more likely to internalize problems than other children [19]. School absence is common. There may be a degree of school refusal or separation anxiety in the younger child. Compared with controls, children with RAP were less confident in their ability to deal with daily stress and less likely to use coping strategies such as accepting the stressor, reframing its significance, or encouraging themselves to keep going [20]. Children with RAP are also more likely to have symptoms of depression directly related to passive coping and inversely related to healthy coping mechanisms and social support [21]. There may be specific issues of importance in the school environment, and discussion with the teachers/school nurse may well be informative in the assessment of triggers and perpetuating factors.

There is often a significantly elevated level of parental anxiety. In the Copenhagen birth cohort of 1327 children, aged 5–7 years old, 308 were identified as having RAP . In those children with higher parental anxiety, functional symptoms were more likely to manifest, a medical consultation more likely to be sought and for the parents to consider these symptoms a burden ( p < 0.001) [12]. Coexistent stressors are often present in families of children with RAP such as unemployment (affecting 34.8 % of parents in one prevalence study) and ‘poor finances’ (affecting 14.8 % of parents) [6].

One study assessed 84 families with a child with RAP, control families with well children and control families with children with asthma, through questionnaires and play assessment [22]. Parental levels of anxiety in children with abdominal pain were similar to those parents of children with asthma. Children with abdominal pain were significantly less able to express their anxieties compared to the other 2 groups ( p < 0.05). Further analyses demonstrated these children were more likely to report functional symptoms (OR: 3.33; 95 % CI 2.84–3.91). The emotional subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) contains a question assessing, ‘often complains of headaches, stomach aches, or sickness’. When this question was removed from the subscale, the relationship between RAP and high scores on the adjusted emotional subscale remained, although at a lower level (OR: 2.03; 95 % CI 1.65–2.50). When these analyses were controlled for the effects of child gender, maternal social class and maternal educational level, the strength of the associations increased.

One study in 2009 noted that children could adopt a sick role in two ways: by either observing how their parents reacted to abdominal symptoms and modifying their own behaviour to cope with symptoms and/or if they received a minor incentive, such as treats, or were excused from normal activities [6]. Parents felt that having their worries and anxieties addressed was a less judgmental approach rather than behaviour changes recommended. Parents often describe feeling helpless and inadequate, and ask doctors to deal with the symptoms through diagnosis and treatment.

Family Stress

There may be significant stresses within the family or the family environment . These can include marital discord, separation, divorce, excessive arguing, extreme parenting, antisocial or conduct disorders or the presence of somatization disorders within the wider family setting may be relevant. Different symptoms expressed in the different environments may well be informative, especially in explaining the triggers to parents. Financial hardship is a common associated feature, as is unemployment [23] .

Children with RAP that becomes chronic, long standing and difficult to treat often come from families with a high frequency of medical complaints, particularly RAP, nervous breakdown, migraine and maternal depression [23] .

Response to Pain

It is important to consider how the child expresses their pain/discomfort, for example ‘I don’t feel well mum…’ and how the parents/carers/child responds. Is any specific attention at the time of pain given, as well as rest periods during pain, and how well do parents deal with their child in pain. Ascertain which medications are given at the time of pain, the degree and speed of response and whether abdominal pain mandates school absence, or a ‘try it and see approach’. Is there a different response seen at home/school/clubs? Many parents will have considered the secondary gain element already; but tactful questioning can help elucidate their thoughts. Is there normal home activity during pain-free periods (especially on days of school, absence)? Also consider, through a family illness history, whether the child’s symptoms during stressors are modelled on other family members.

Physical Factors

It may be difficult to separate organic from nonorganic completely as functional symptoms may manifest in patients with pre-existing disease, such as Crohn’s. Similarly, missing organic disease in children adversely impacts on the relationship of the clinician with the family. Psychological complications of organic disease are common.

Organic factors may be identified in children with nonorganic symptoms, such as H. pylori or coeliac disease, and it is important to explain to the family that if the symptoms persist despite appropriate treatment (e.g. triple therapy or gluten-free diet, respectively), that the identified organic factor may not be causing the symptoms but simply coexisting. One study compared the rates of positivity for coeliac disease in 200 children referred with RAP compared to controls: they found that the frequency of antiendomysial antibody positivity in children with RAP was similar (1 in 92 (1 %; 95 % CI 0–6 %) compared with 1 in 81 in controls (1 %; 95 % CI 0–7 %)) [24]. One review of six studies assessing the association between H. pylori and RAP found that the evidence for a causal relationship was inconsistent; of the five case-control studies reviewed, the odds ratios ranged from 0.32 to 1.80 [25].

Other physical stressors include poor diet and obesity . A population of 925 children (mean age of 9.5 years) were assessed by questionnaires. Children with BMI ≥ 95 % percentile (obese) reported more RAP symptoms compared to those not obese (33.3 vs 22.5 %) (OR = 1.8, p = 0.01) [26]. The inverse correlation between fruit consumption and RAP prevalence was significant, with RAP prevalence at 20 % among children eating more than three serving of fruit per week compared to 40 % of those who did not consume any fruits ( p < 0.002). Sedentary behaviour is a likely risk factor, perpetuated by pain, with up to 20 % of children highlighting that exercise triggers their symptoms, but exercise as part of an overall strategy to encourage relaxation and distraction can reduce pain scores [27].

Visceral Hypersensitivity in the Context of Physiological Peristalsis

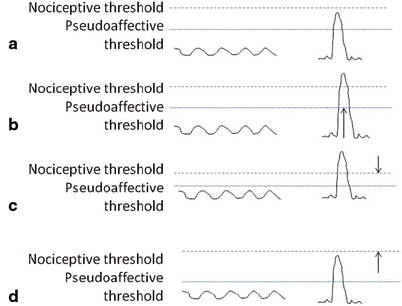

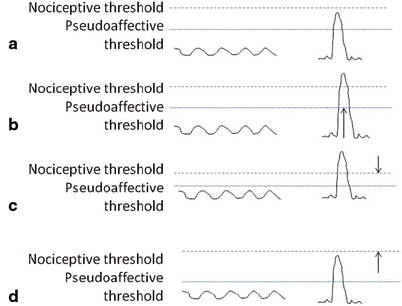

Normally, the contraction of the GI tract follows two patterns: rhythmic phasic contractions (continuously) and giant migrating contractions (several times a day). These peristaltic mechanisms should not generally cause pain. In patients with FAP, increased levels of substance P and other nociceptive transmitters lower the threshold for the child’s perception of pain [28]. Adult models have demonstrated increased concentration of nociceptive transmitters, and neuronal hypersensitivity at the mucosal, spinal and cerebral levels, causing visceral hypersensitivity and intestinal dysmotility [28]. The presence of physical and psychological stressors exacerbate this ‘visceral’ hypersensitivity, and conversely effective stressor control through appropriate parental understanding, reassurance and distraction downregulates the production of these nociceptive neurotransmitters [29]. This reduces the perception of these normal peristaltic waves as painful (see Fig. 19.1).

Fig. 19.1

In this graphic representation in a well child (A) neither RPC or GMC pierce the nociceptive threshold to cause pain. However, in a child with gastroenteritis (child B) the GMCs are of greater amplitude, breaking the nociceptive threshold, and causing pain. Infection can be a stressor for RAP, for example 1/3 of patients after a bout of gastroenteritis develop IBS, with evidence of mucosal lymphocytic infiltration on biopsies. In a child with FAP (child C): the visceral hypersensitivity has lowered the nociceptive threshold, causing a perception of pain. The aim is: through understanding and reassurance, the nociceptive threshold will return to normal (D). RPC retrograde peristaltic contractions GMC giant migrating contractions. (Reproduced with kind permission from [30])

A simpler explanation more suitable for younger children is that of ‘butterflies in the tummy’ is triggered by stressful events such as an exam or big performance, but some children have got into a cycle where they are on the more extreme end of this spectrum, and their abdominal discomfort is severe, and impacting adversely on their functioning, but that this does not indicate serious underlying organic disease. Addressing underlying stressful triggers is important for symptom improvement.

For abdominal migraine , although similar underlying themes emerge, the coexistence with headaches has led researchers to look at vascular instability and mast cells. In migraine, which is more common in those with atopic diseases, there is evidence for the perivascular aggregation of mast cells. Secretion of nociceptive transmitters such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptides cause mast cells to release proinflammatory, vasoactive and neurosensitizing peptides, causing the vascular instability and visceral hypersensitivity seen in migraine and abdominal migraine. This is exacerbated by higher levels of corticotrophin-releasing hormone (elevated by stress), which also elevates interleukin-6 (IL-6) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [31]. This could potentially explain the therapeutic effect of pizotifen, a histamine antagonist in mediating mast cell action, or the frequently tried ‘migraine diet’, although many patients do not respond significantly to these measures, and understanding stressors, using the biopsychosocial model outlined above, may well be the more effective management strategy [31]. In those few patients who suffer significantly with cyclic vomiting syndrome , some benefit from early intervention including intravenous fluids and antiemetics such as ondansetron, to reduce the effects from vascular instability potentiated by dehydration. Further details are available in Chap. 25.

Is RAP Really Painful?

Using rectal balloon distension, children with FAP and IBS sensed rectal pain at a lower pressure threshold (median 16 and 19.5 mmHg, respectively) compared with controls and children with functional dyspepsia (42 and 41.5 mmHg, respectively) [32]. Further, the pain referred to the T8 to L1 dermatomes (i.e. abdominal projections) in the FAP and IBS children, whereas pain was referred to the S3 (perineal) dermatome in control and dyspepsia groups. In 20 children with RAP, pain symptoms after colonoscopy (19 IBS, 1 FAP) were compared to 20 children with IBD (15 Crohn’s, 5 ulcerative colitis) [33]. Children with RAP had greater baseline pain scores and a longer duration of pain post procedure than did children with IBD.

Clinical Assessment

This is the cornerstone of the patient journey, to exclude organic disease and identify key features to make a convincing diagnosis. A full history and examination aims to exclude organic pathology and, if no concerning features of disease are found (Table 19.5), a targeted set of investigations should be initiated, that should be one-stop, rather than multiple and consequent investigations which may increase family anxiety and exacerbate symptoms should be avoided unless clinically indicated. Red flags may still be present in functional conditions, but should lower the threshold for further investigation.

History and Examination

A detailed history of the abdominal pain and any associated features is essential because it is important to assess for organic disease, identify triggers, and build a rapport with children and parents ascertaining their worries and concerns. A detailed family history, including illnesses, and social history is important, including how the child is coping at school.

In assessing the pain, consider character type and frequency and consider a symptom diary when a history is vague. Associated features, for example with physiological events, and relieving (e.g. response to analgesia)/exacerbating factors, and specific questions looking for functional features should be considered. Past history, stress factors and perpetuating factors are key, as is ascertaining how pain is dealt with when it occurs (specific attention or a rest period at the time of pain. Consider how the child integrates in pain-free periods. Assessing family dynamics, family history as well as a family illness history is important, as is ascertaining their concerns. Discussion about growth, and where appropriate pubertal progression, should also be considered.

Ascertaining specific worries that parents may have (e.g. cancer/coeliac disease) is also a key part of the initial discussion, and investigations may need to take account of this.

Establish gently how illnesses are dealt with in the family for the index case and other family members (family illness history).

The severity of pain is highly subjective, and a parental description of ‘very severe pain’ in itself would not point towards organic disease but highlights the family anxiety about the pain.

Apley identified that pain away from the umbilicus was more likely to be organic [1]; however, more recent studies have challenged this. One study in 2007 assessed 77 children with RAP compared to 33 controls and found that although the umbilicus was the most common site of pain identified, children with RAP reported similar rates of pain localized throughout the abdomen compared to controls; and many of those children with RAP had features consistent with IBS [34].

Pain during sleep is often considered a concerning feature, but a NASPGHAN subcommittee has challenged the association of ‘night pain’ as a sensitive or specific indicator of organic disease [35].

Examination should focus on identifying red flag signs as listed in Table 19.6, especially extra-intestinal signs including fever, weight loss, poor growth, joint signs, skin rashes, and aphthous ulcers. Plotting height and weight is essential, and measurements and parental height should be used in considering growth potential. Asking about pubertal status in teenagers is important, as poor growth in puberty or delayed onset of puberty can be a subtle sign of organic disease. On abdominal examination, the site of the pain can be assessed with care, and exclusion of organomegaly and perineal disease is also important. Peri-anal examination is essential to detect peri-anal disease which can be painless or embarrassing for the child to discuss.

Table 19.6

‘Red Flag’ symptoms and signs in children with chronic abdominal pain

‘Red Flag’ symptoms in children with chronic abdominal pain | |

|---|---|

Involuntary weight loss | Chronic severe diarrhea |

Slowing of linear growth | |

Gastrointestinal blood loss | Significant vomiting (especially if bilious) |

Gynaecological symptoms | Urinary symptoms |

Family history of inflammatory bowel disease/coeliac disease | |

‘Red Flag’ signs | |

Clubbing | Perineal changes (tags/fistulae) |

Mouth ulcers | Anorexia/delayed puberty |

Abdominal masses | Hypertension/tachycardia |

Red Flag Features

Important organic causes will often have red flag symptoms, and general practitioners (GPs)/pediatricians can reassure families of the low risk of disease, given normal baseline investigations and the reassurance of further investigations if red flags appear. You should ask whether any of the following “red flag” symptoms are present, which would raise the suspicion of organic disease:

Unexplained fever

Involuntary weight loss

Poor growth (you should plot the child’s height and weight)

Joint problems

Skin rashes

Vomiting, particularly if bile stained

Pain that is referred to the back or shoulders

Urinary symptoms

Family history of inflammatory bowel disease, coeliac disease or peptic ulcer disease

Peri-anal disease

Occult or gross blood in the stool

Age under 5 years.

Differential Diagnosis of Functional Pain

Commoner important organic diseases are highlighted in Table 19.7.

Table 19.7

Organic diseases that can manifest with recurrent abdominal pain

Organic diseases that can manifest with recurrent abdominal pain | |

|---|---|

gastro-esophageal reflux/esophagitis | Inflammatory bowel disease |

Peptic ulcer disease | Constipation |

Helicobacter pylori infection | Pancreatitis |

Coeliac disease | Hepato-biliary disease |

Food allergy/intolerance < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |