Terminology

Definition

CECT findings

Acute peripancreatic fluid collection

Peripancreatic fluid occurring in the setting of interstitial edematous pancreatitis within the first 4 weeks of acute pancreatitis

Homogeneous fluid adjacent to the pancreas confined by fascial planes with no recognizable wall

Pancreatic pseudocyst

An encapsulated, well defined collection of fluid, but no or minimal solid components which occur > 4 weeks after the onset of interstitial edematous pancreatitis

Well-circumscribed, homogeneous, round or oval fluid collection. No solid components. Well-defined wall. Occurs only in interstial edematous pancreatitis

Pancreatic abscess collection

Similar to a pancreatic pseudocyst, but infected. Typically occurs after bacterial or fungal contamination

Similar to pancreatic pseudocyst. Occurs because of bacterial or fungal contamination of a fluid collection. Typically occurs in the setting of pancreatic duct leak/disruption after contamination

Acute necrotic collection

A collection of both fluid and solid components (necrosis) occurring during necrotizing pancreatitis. These are immature collections <4 weeks after the onset of severe acute pancreatitis

Heterogeneous, varying of nonliquid density. No encapsulating wall. Intrapancreatic and/or extrapancreatic

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis

A mature, encapsulated acute necrotic collection with a well-defined inflammatory wall. These tend to mature > 4 weeks after the onset of necrotizing pancreatitis

Heterogeneous liquid and nonliquid density. Well-defined wall. Intrapancreatic and/or extrapancreatic

In approaching patients with PFCs, a proper history and physical examination is important. In the absence of a prior history of pancreatitis, a neoplastic etiology should be considered more a pseudocyst and management changes from a therapeutic drainage procedure to a diagnostic fine needle aspiration. Cross-sectional imaging with CECT scan will help define the contents of the PFC (liquid, solid, or both), whether there is evidence of pancreatic necrosis, if the cyst wall is well-formed and amenable to endoscopic intervention. Liquefied collections are easily drained transmurally or via a transpapillary approach. The transmural approach involves transmural enterotomy creation (transgastric or transduodenal) and placement of polyethylene stents. On the other hand, collections with solid debris require larger transmural enterotomies and placement of large caliber stents and possible endoscopic debridement.

Delineation of ductal anatomy and communication with the PFC may require magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). While ERCP will also clarify this issue, there is a risk for infection and an ERCP is typically performed with therapeutic intent. The management approach to a PFC can be formulated only after these issues are ascertained.

Unfortunately, the term pancreatic pseudocyst is commonly misused to describe walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) . When mischaracterized as a pancreatic pseudocysts (PC), patients with the WOPN may develop secondary infection, as the devascularized solid material cannot be evacuated via the small caliber stents typically placed to drain a PC. The Atlanta classification was intended to help define pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections accurately and guide appropriate management.

Liquefied Pancreatic Fluid Collections

Acute peripancreatic fluid collections (APFCs) are immature fluid collections that develop in the early phase of interstitial edematous acute pancreatitis. APFCs lack a true wall. They are mainly confined to the retroperitoneal space. These APFCs are usually sterile. They may get infected spontaneously or following iatrogenic contamination at ERCP. The APFCs usually resolve without intervention. APFCs that persist for > 4 weeks are likely to develop into a pseudocyst.

PCs arise from focal disruption of the pancreatic duct in which amylase-rich pancreatic fluid becomes surrounded by a well-defined nonepithelialized wall. PCs contain to minimal solid material. PCs may develop following acute pancreatitis or in a setting of chronic pancreatitis . In chronic pancreatitis, a stricture in the main pancreatic duct or obstructing pancreatic calculus may result in the formation of a PC. The pancreatic ductal hypertension and resultant blowout of the pancreatic duct (leak) are believed to result in a PC.

Indications for Drainage of Liquefied Pancreatic Fluid Collections

Patients who develop liquefied collections do not necessarily require drainage. Drainage of these liquefied collections is driven by symptoms and/or because of infection. Infection, bleeding, and perforation occur infrequently following the drainage of PCs and these potential risks outweigh the benefit of drainage in an asymptomatic patient. Symptoms associated with large PCs are abdominal pain, early satiety with weight loss, gastric outlet obstruction, or obstructive jaundice.

Previously PCs that were > 6 cm were referred for drainage even if asymptomatic. Size is, however, no longer used as sole criteria for drainage. There is a chance that PCs will resolve spontaneously over time. In a retrospective review of 68 patients with a walled-off pancreatic fluid collection followed conservatively, 63 % either had spontaneous fluid collection resolution or remained well without symptoms or complications at a mean follow-up of 51 months. However, patients need to be counseled that observation alone does carry risks. In the same series, there was a 9 % incidence of serious complications, typically during the first 2 months after the diagnosis. Complications included pseudoaneurysm formation, free perforation, and spontaneous abscess formation. An additional third of the patients underwent elective surgery due to increasing size of the fluid collection and pain [2]. In another series of 75 patients, significant abdominal pain, complications, or progressive enlargement of a fluid collection led to surgery in 52 % of the patients. The remainder of the patients who were followed conservatively had no symptoms, with either persistence of their fluid collections or a gradual decrease in size. While walled-off pancreatic fluid collections were smaller in the conservatively managed group than in patients requiring surgery, neither the etiology of the fluid collection nor the computed tomography (CT) criteria could predict successful outcome with a conservative approach [3]. The decision regarding conservative approach versus an intervention should be tailored individually to the clinical scenario.

In assessing whether a patient needs drainage, a proper pre-drainage evaluation needs to be performed are a number of cystic lesions that may mimic a PFC. The patient’s history is critically important in establishing a history of pancreatitis and possible etiologies (trauma, recent surgery, alcohol use, and gallstones). If there is no history of pancreatitis, then one must consider other lesions that may mimic a PFC (cystic neoplasm of the pancreas, pseudoaneurysm, lymphocele, cystic degeneration of a neoplastic lesion).

The review of cross-sectional imaging for solid components and collateral vessels will help determine the feasibility of drainage. A pseudoaneurysm is generally considered to be an absolute contraindication to endoscopic drainage and has to be addressed by an arterial embolization prior to endoscopic therapy . Unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding, sudden increase in size of collection, and unexplained sudden anemia may be clues to a bleeding pseudoaneurysm. An magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a triple-phase or dynamic bolus CT-scan with early imaging during the arterial phase should be performed in all patients prior to a pseudocyst drainage procedure to avoid catastrophic bleeding from a pseudoaneurysm that may occur following decompression of the pseudocyst. In a series of 57 patients referred for endoscopic drainage of pancreatic walled-off pancreatic fluid collections , five pseudoaneurysms were detected prior to the drainage procedure.[4]

The pre-procedure evaluation should also include assessment of the coagulation profile. Patients who are cirrhotic or are hemophiliacs might not be suitable for drainage due to the risks of bleeding. A patient on anticoagulation will also need to have the medications discontinued and possibly reversed. Some of the newer anticoagulation medications do not have reversal agents and will need sufficient time half-life before transmural drainage is performed.

Drainage of Liquefied PFCs

Liquefied PFCs may be drained by transpapillary approach, transmural approach, or a combination of these. After careful evaluation of cross-sectional imaging, a decision can be made based on the size and location of the collection, adherence to the gastric wall or duodenum, and whether the collection is in continuity with the pancreatic duct. It is extremely important that the PFC is adherent to the gastrointestinaI (GI) tract if transmural drainage is to be performed. Nonadherence to the GI tract can result in leakage of cystic contents into the retroperitoneal space and perforation once the cyst is decompressed. A general practice is to allow the PFC to mature for at least 4 weeks and visualization of a mature wall/peel around the cyst on cross-sectional imaging. There is one report of using a fully covered self-expanding metal stent (fcSEMS) for PFCs with indeterminate adherence. A cyst resolution was achieved in 78 % of patients.[5]

Transpapillary Drainage

Collections that are small (≤ 6 cm) and communicate with the main pancreatic duct, can be drained by ERCP with the placement of a polyethylene pancreatic duct endoprosthesis. This might be the safest approach in collections that are not adherent to the GI tract. If there is obstruction of the main pancreatic duct from stones or strictures, it is important that the guide-wire is advanced upstream of the obstruction for successful placement of an endoprosthesis. If an obstruction downstream to the PFC cannot be traversed with a guide-wire, transpapillary drainage will not be successful.

In patients undergoing transpapillary drainage, a pancreatic duct sphincterotomy is usually performed, but is not absolutely necessary. The size of the pancreatic duct stent placed is based on the duct diameter. A larger pancreatic duct diameter can accommodate a larger diameter stent. It is important to choose a stent of appropriate caliber to minimize stent-induced changes in the normal pancreatic ducts. Depending on the caliber of the pancreatic duct, 5 F, 7 F, 8.5 F, or even 10 French stents may be used in this situation.

Transmural Drainage

Transmural drainage of liquefied PFCs is a well-established technique. The majority of transmural drainage of PFCs are performed with EUS guidance. Drainage of PCs can be performed at the site of maximal bulge without EUS guidance. However, as noted below, EUS guidance provides information which probably enables a safer technique and may alter the approach, particularly if a large amount of previously unrecognized solid debris is present within the PC.

EUS has several important advantages to non-EUS guided approaches. The first and the most important advantage is endosonographic visualization of intervening vessels between the gastric/duodenal wall and the PFC. [6, 7] (Figs. 1 and 2) The ability to guide the EUS needle into the collection while avoiding intervening vessels minimizes the risk of bleeding. Secondly, EUS-guided approaches can assess adherence of the PFC to the GI tract and the distance between the gastric mucosa and the cyst wall. The third advantage is that a number of PFCs do not form extrinsic compression on the GI tract, so the EUS guidance is critical in evaluating and identifying the location of the PFC. Finally, EUS will clarify the consistency of cyst contents.

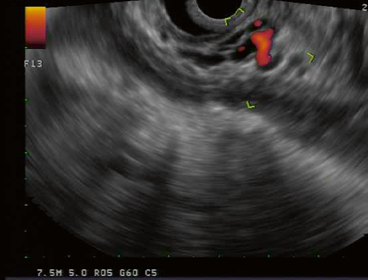

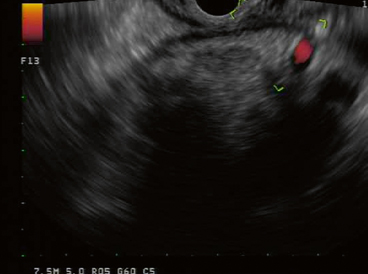

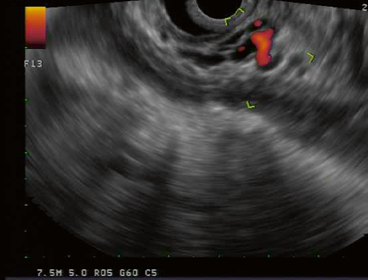

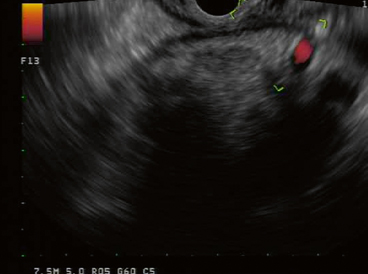

Fig. 1

EUS evaluation of gastric wall of WOPN. Multiple collateral vessels sonographically visualized precluding transmural drainage. EUS endoscopic ultrasonography, WOPN walled-off pancreatic necrosis

Fig. 2

EUS evaluation of gastric wall of WOPN. Multiple collateral vessels sonographically visualized precluding transmural drainage. EUS endoscopic ultrasonography, WOPN walled-off pancreatic necrosis

Technique

EUS-guided drainage of a PFC is performed with a therapeutic linear echoendoscope, which typically accommodates 10 French accessories and has Doppler capabilities. Utilizing a linear echoendoscope, one-step drainage is possible of PFCs. This has been reported successful in > 94 % of cases [8, 9]. As liquefied PFCs contain no or minimal solid material, the drainage through transgastric or transduodenal punctures with placement of multiple 10 Fr stents will result in successful drainage of most PCs. (Figs. 3 and 4)

Fig. 3

CECT scan revealing large pseudocyst. The large PFC is causing significant extrinsic compression of the stomach. CECT contrast-enhanced computed tomography, PFC pancreatic fluid collections

Fig. 4

CECT scan after transmural drainage of pseudocyst. The pseudocyst has completely collapsed after drainage. Two double-pigtail stents noted across the gastric wall. CECT contrast-enhanced computed tomography

The linear echoendoscope is passed to the level of the PFC. Once the PFC is endosonographically identified, the optimal point for entry should be carefully evaluated. The site is evaluated for a maximal point of adherence and intervening blood vessels. Once the optimal site is identified, a 19 G endoscopic ultrasonography fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) needle is passed under endosonographic guidance into the collection. A 19 G needle is utilized as it allows passage of a 0.035 in. guide-wire. Fluid is initially aspirated using a suction syringe from the PFC. The fluid aspirated can be sent for a cell count and differential, gram stain and culture. The suction syringe is then removed and a long 0.035 in. guide-wire is advanced down the EUS-FNA needle. The guide-wire is then visualized endosonographically and fluoroscopically to coil within the collection. (Fig. 5) The passage of the guide-wire into the PFC secures access and the needle is removed, leaving the wire in place. This next step is creating a small tract across the GI tract to allow the passage of a dilating balloon. This can be achieved using “hot” access or “cold” access. A hot access utilizes current across a metal wire to help create the tract. A needle knife with a “bent” needle can be passed over the guide-wire and used to create the enterotomy tract to allow passage of a dilating balloon. The major risk of using a needle-knife is bleeding. This technique is especially useful, if the GI tract is fibrotic from previous PFC drainage or previous surgery. A cold access utilizes small dilating balloons or tapered dilating catheters to create the initial enterotomy tract, so that larger dilating balloons can pass across the tract. Once the enterotomy tract is established, the enterotomy can be dilated to 10 mm. It is not necessary to create an enterotomy greater than 10 mm as liquefied collections should easily drain across a 10 mm enterotomy tract. Control and suction of fluid as it evacuates from the cyst into the stomach is crucial to avoid pulmonary aspiration. Aspiration of evacuating fluid can be minimized by intubating the patient for the procedure and/or slowly deflating the initial dilating balloons and prompt suctioning the evacuating fluid as it enters the stomach. This method of partially deflating the balloon over several minutes in the tract will help avoid the sudden entrance of a large volume of fluid into the stomach.

Fig. 5

Fluoroscopic image of a therapeutic linear echoendoscope and guidewire coiling within PFC. PFC pancreatic fluid collections

Once the enterotomy is dilated to 10 mm, the use of double pigtail stents rather than straight stents are recommended to provide ongoing drainage. The pigtails on either end will minimize the chance of spontaneous migration across the enterotomy and additionally, as the collection collapses when the fluid drains, the pigtail within the collection will not impact on the wall within the collection and cause injury/bleeding. Straight stents will have a higher chance of spontaneous migration into or out of the collection and might impact on the wall of the collection. The use of long fcSEMS, while reportedly successful, are not typically utilized for liquefied PFCs due to the prohibitive costs and concern for bleeding from within the cavity as the collection collapses. The newer Axios lumen apposing fcSEMS by Xlumena (Figs. 6, 7, 8) might avoid the issues with impaction on the opposite wall. The Axios stent might also have a role in PFCs with suspected nonadherence[5, 10] (Fig. 9).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Fig. 6

Xlumena Axios delivery catheter

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree