Flat Urothelial Lesions

There are four main reasons a surgical pathologist is asked to evaluate flat (cystoscopically apparent or unapparent) lesions. The first two indications involve multiple random biopsies by the cold cup biopsy technique (a) in patients previously diagnosed with noninvasive or lamina propriainvasive papillary tumors, who are on surveillance for bladder cancer, and (b) in patients who are diagnosed with papillary bladder carcinoma for the first time. The aim of these biopsies is to detect flat intraurothelial disease, which suggests urothelial instability, multifocality, and proclivity for disease progression. The third indication is in patients with hematuria, dysuria, and increased frequency of micturition, who have positive urine cytology, positive FISH UroVysion, or are at high risk of development of bladder cancer. The aim is to detect urothelial carcinoma in situ (CIS), which may or may not be cystoscopically apparent. The fourth indication is in patients without a high risk of bladder cancer but who present with urinary symptoms similar to those listed and do not respond to routine medical treatments. In this setting, biopsies are performed to evaluate other causes for the symptoms. Significant flat urothelial disease may be inapparent by cystoscopy, and this has promulgated the concept of performing random bladder biopsies in patients with cancer, resulting in most of the flat lesions seen clinically (1).

APPROACH TO THE DIAGNOSIS OF FLAT LESIONS

The World Health Organization (WHO)/International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) classification of flat intraurothelial lesions is outlined in Table 2.1 (2, 3, 4). Because WHO has accepted the nomenclature for flat lesions used in the WHO/ISUP (1998) in its entirety, the system is currently referred to as WHO (2004)/ISUP. The approach to the diagnosis of lesions within this classification requires attention to several organizational and cytologic features within the urothelium, the constellation of the presence or absence of which helps make the correct diagnosis (5) (Table 2.2).

On low-power examination, one should pay attention to several features including the thickness of urothelium, overall polarity, presence or absence of cytoplasmic eosinophilia and neovascularity at the base of the urothelium. Observation regarding the thickness of the urothelium may provide

useful clues. It is normally three to seven layers in thickness, depending on the state of distention. Denudation may be seen in reactive conditions (trauma or infection) or CIS. Hyperplastic urothelium may be encountered in the entire spectrum of flat intraepithelial lesions (reactive atypia, dysplasia, and CIS) and its presence merits evaluation of cytologic features, on the basis of which the diagnosis is ultimately made. Other features assessed at low power include polarity, nuclear crowding, and cytoplasmic clearing. In the normal urothelium, cells are arranged perpendicularly to the basement membrane, with an orderly organization of the basal cells, intermediate cells, and superficial umbrella cells. The loss of normal polarity and presence of nuclear crowding are often indicative of intraurothelial neoplasia. Loss of cytoplasmic clearing (increased eosinophilia) is also a sign of dysplasia or CIS. Nucleomegaly is objectively determined by comparison if normal urothelium is clearly present in the biopsy. If normal urothelium is not present, stromal lymphocytes may also be used for size comparison. The

larger nuclei in CIS are often five times the size of a normal lymphocyte, whereas the nuclear size of normal urothelium and dysplastic urothelium is only approximately twice the size of lymphocytes, aiding in their distinction from CIS (6). The presence of dysplasia is confirmed by unequivocal nuclear atypia (nuclear border and nuclear chromatin abnormalities) but does not meet the threshold for CIS. The presence of nuclear pleomorphism, frequent mitoses (including atypical mitotic figures or surface mitoses), and prominent nucleoli (single or multiple) throughout much of the urothelium favors a diagnosis of urothelial CIS over that of urothelial dysplasia or reactive changes. Neovascularization in a bladder biopsy without history of previous treatment suggests the presence of a host response to an intraurothelial neoplastic process.

useful clues. It is normally three to seven layers in thickness, depending on the state of distention. Denudation may be seen in reactive conditions (trauma or infection) or CIS. Hyperplastic urothelium may be encountered in the entire spectrum of flat intraepithelial lesions (reactive atypia, dysplasia, and CIS) and its presence merits evaluation of cytologic features, on the basis of which the diagnosis is ultimately made. Other features assessed at low power include polarity, nuclear crowding, and cytoplasmic clearing. In the normal urothelium, cells are arranged perpendicularly to the basement membrane, with an orderly organization of the basal cells, intermediate cells, and superficial umbrella cells. The loss of normal polarity and presence of nuclear crowding are often indicative of intraurothelial neoplasia. Loss of cytoplasmic clearing (increased eosinophilia) is also a sign of dysplasia or CIS. Nucleomegaly is objectively determined by comparison if normal urothelium is clearly present in the biopsy. If normal urothelium is not present, stromal lymphocytes may also be used for size comparison. The

larger nuclei in CIS are often five times the size of a normal lymphocyte, whereas the nuclear size of normal urothelium and dysplastic urothelium is only approximately twice the size of lymphocytes, aiding in their distinction from CIS (6). The presence of dysplasia is confirmed by unequivocal nuclear atypia (nuclear border and nuclear chromatin abnormalities) but does not meet the threshold for CIS. The presence of nuclear pleomorphism, frequent mitoses (including atypical mitotic figures or surface mitoses), and prominent nucleoli (single or multiple) throughout much of the urothelium favors a diagnosis of urothelial CIS over that of urothelial dysplasia or reactive changes. Neovascularization in a bladder biopsy without history of previous treatment suggests the presence of a host response to an intraurothelial neoplastic process.

TABLE 2.1 The WHO/ISUP Classification of Flat Intraurothelial Lesions | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

TABLE 2.2 Histologic Parameters Useful in the Evaluation of Flat Lesions with Atypia | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FEATURES OF FLAT INTRAUROTHELIAL LESION CATEGORIES

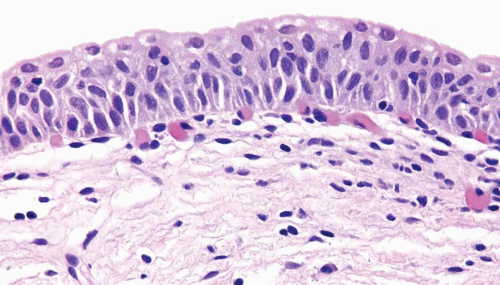

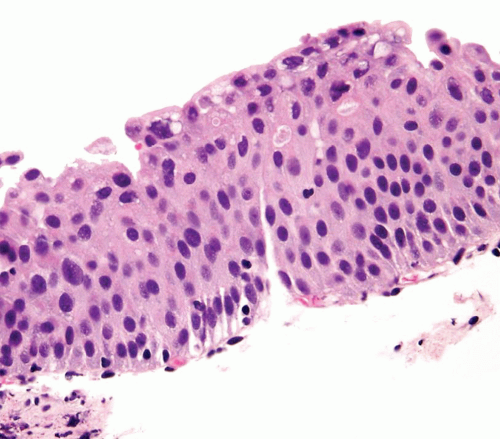

Normal

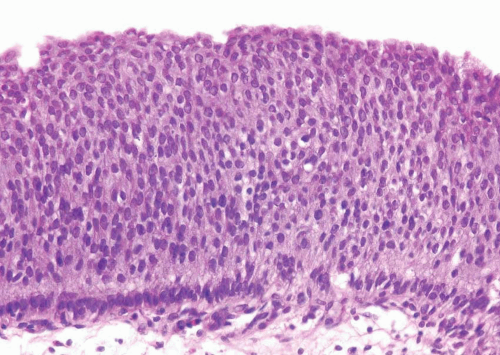

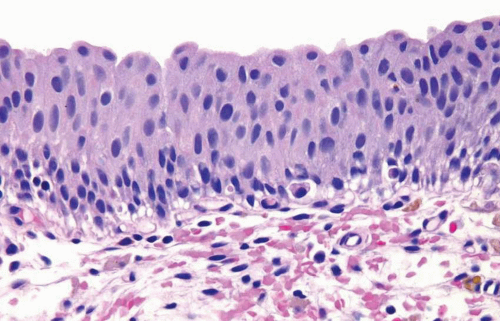

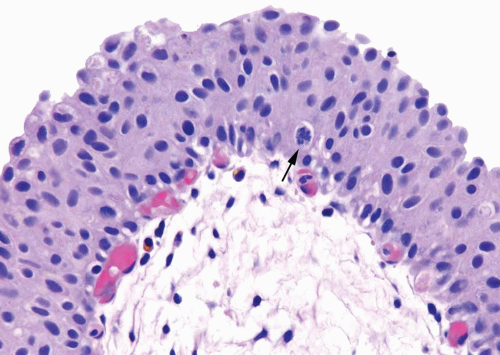

The normal urothelium, as mentioned previously, is composed of three cell types: basal, intermediate, and superficial, arranged in three to seven cell layers, with a thickness varying depending on the state of distention (Fig. 2.1) (efigs 2.1-2.7). The basal cells are small and hyperchromatic, and they usually form a single cell layer. The intermediate cells constitute the bulk of the urothelium and are oriented perpendicular to the basement membrane, with the nuclei usually oval to round in tissue sections. Nuclear grooves are frequently identified. The cytoplasm is clear to amphophilic. The superficial or umbrella cells are arranged parallel to the basement membrane and are large, with one cell typically spanning or covering several intermediate cells (like an umbrella). The nucleus is small and the cytoplasm is voluminous and clear or eosinophilic. Mild degrees of architectural variation (apparent loss of polarity) without cytologic atypia are considered acceptable to be designated as normal (Figs. 2.2, 2.3). This is often due to tangential or thick sectioning.

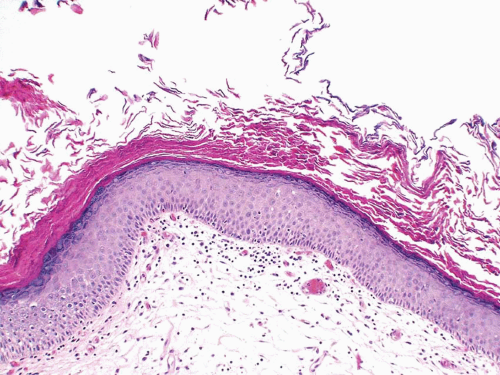

Squamous Metaplasia

Nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium metaplasia, particularly in the trigone area, is a common finding in premenopausal women and is responsive to estrogen production (efigs 2.8-2.12). This type of squamous mucosa is characterized by abundant intracytoplasmic glycogen and lack of keratinization, making it histologically similar to vaginal or cervical squamous epithelium (Fig. 2.4) (See Chapter 9 for additional images) (7). It is likely that trigonal squamous mucosa in women represents a normal histologic variant unassociated with local injury. Under other pathologic conditions, the metaplastic squamous epithelium, that is, nonkeratinizing squamous mucosa in males and/or in nontrigonal locations or mucosa with keratinization in either sexes, may exhibit parakeratosis and even a granular layer (8) (Fig. 2.5) (efig 2.13). This metaplastic epithelium is

not preneoplastic per se but, under some circumstances, may lead to squamous carcinoma (see Chapter 9), particularly when multifocal and extensive.

not preneoplastic per se but, under some circumstances, may lead to squamous carcinoma (see Chapter 9), particularly when multifocal and extensive.

FIGURE 2.3 Tangentially sectioned cytologically appearing normal urothelium with umbrella cells showing slight atypia. |

Flat Urothelial Hyperplasia

The urothelium is markedly thickened and, importantly, lacks cytologic atypia (Fig. 2.6) (efigs 2.14-2.16). Rather than requiring a specific number of cell layers, marked thickening and/or increased cell density within urothelium (increased cells per unit area) is needed to diagnose flat hyperplasia.

This lesion may be seen in the flat mucosa adjacent to low-grade papillary urothelial lesions. When seen alone in a de novo setting, there are no data to suggest that it has a premalignant potential.

This lesion may be seen in the flat mucosa adjacent to low-grade papillary urothelial lesions. When seen alone in a de novo setting, there are no data to suggest that it has a premalignant potential.

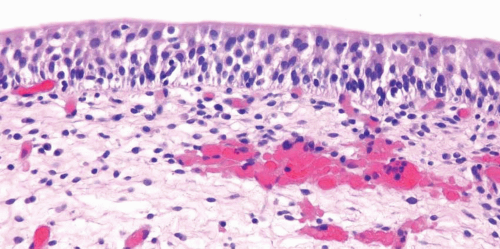

Reactive Atypia

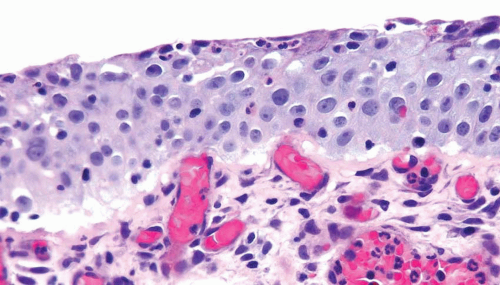

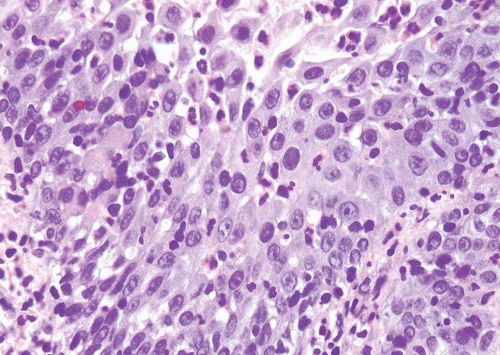

Nucleomegaly is the most prominent finding in reactive urothelial atypia, but the cells often have a single prominent nucleolus and evenly distributed vesicular chromatin (Fig. 2.7) (efigs 2.17-2.28). The nuclei are frequently round, and the nuclear pleomorphism is lacking (9). Architecturally, the cells maintain their polarity perpendicular to the basement membrane, although a minimal loss of polarity may be evident. The mitotic rate may be increased with mitoses present predominantly in the basal and intermediate urothelium, but atypical forms are not seen. Intraurothelial

acute or chronic inflammation is commonly identified (Figs. 2.8, 2.9 and 2.10). It is important to recognize that even intraepithelial lymphocytes, by themselves, can result in reactive changes. The cytoplasm may become more basophilic or eosinophilic, with loss of cytoplasmic clearing. Clinical history of stones, infection, or frequent instrumentation may be present (10). Reactive urothelium may be denuded with only a single layer of basal cells remaining; the residual cells are not hyperchromatic, are not enlarged, and do not possess nuclear membrane irregularity. The umbrella cells frequently undergo reactive change alone and exhibit multinucleation or nucleomegaly, often with cytoplasmic vacuolation. Although reactive

conditions share the presence of enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitoses with CIS, in reactive conditions nuclei are uniform in size and shape with vesicular nuclei as opposed to the often hyperchromatic nuclei of CIS. Furthermore, most cases of CIS are not associated with intraepithelial inflammation.

acute or chronic inflammation is commonly identified (Figs. 2.8, 2.9 and 2.10). It is important to recognize that even intraepithelial lymphocytes, by themselves, can result in reactive changes. The cytoplasm may become more basophilic or eosinophilic, with loss of cytoplasmic clearing. Clinical history of stones, infection, or frequent instrumentation may be present (10). Reactive urothelium may be denuded with only a single layer of basal cells remaining; the residual cells are not hyperchromatic, are not enlarged, and do not possess nuclear membrane irregularity. The umbrella cells frequently undergo reactive change alone and exhibit multinucleation or nucleomegaly, often with cytoplasmic vacuolation. Although reactive

conditions share the presence of enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitoses with CIS, in reactive conditions nuclei are uniform in size and shape with vesicular nuclei as opposed to the often hyperchromatic nuclei of CIS. Furthermore, most cases of CIS are not associated with intraepithelial inflammation.

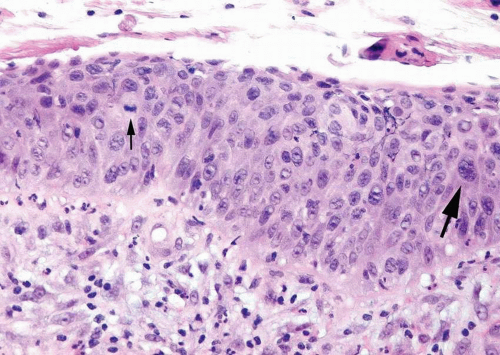

FIGURE 2.8 Reactive urothelium with scattered lymphocytes and neutrophils within urothelium showing mitotic figure (arrow). |

Urothelial Atypia of Unknown Significance

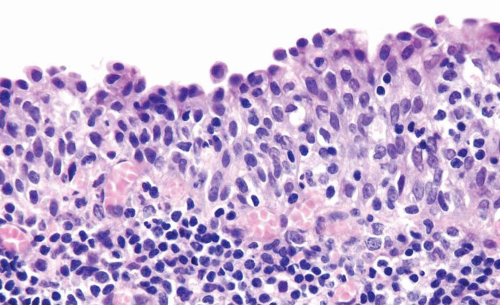

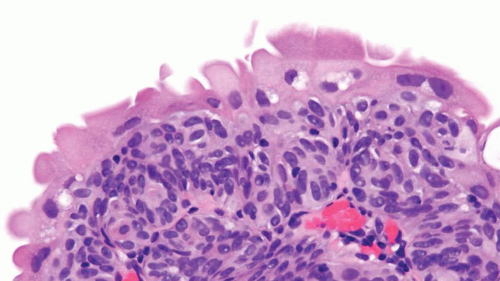

This term may be used as a descriptive category in cases with inflammation, in which the severity of atypia appears to be out of proportion to the extent of inflammation such that dysplasia or CIS cannot be confidently excluded (Figs. 2.11, 2.12) (efig 2.29). The message conveyed to the urologist by use of this diagnostic terminology is that the patient should

be followed up after inflammation subsides. This is neither a disease nor a diagnostic entity, but merely a descriptive term used in a biopsy in which the flat lesion with atypia cannot be diagnosed with certainty into reactive, dysplastic, or CIS categories. This term should also not be loosely used as a “wastebasket” term by pathologists for lesions with minimal atypia that may well fall into the spectrum of “normal.”

be followed up after inflammation subsides. This is neither a disease nor a diagnostic entity, but merely a descriptive term used in a biopsy in which the flat lesion with atypia cannot be diagnosed with certainty into reactive, dysplastic, or CIS categories. This term should also not be loosely used as a “wastebasket” term by pathologists for lesions with minimal atypia that may well fall into the spectrum of “normal.”

FIGURE 2.11 Atypia of unknown significance with scattered hyperchromatic nuclei yet prominent inflammation. |

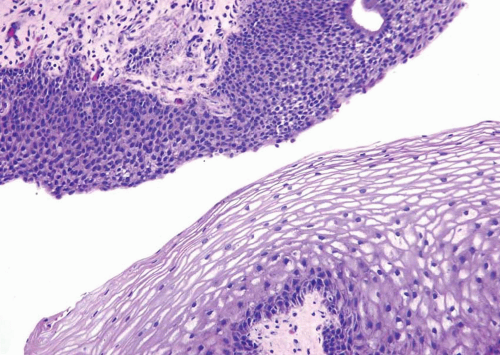

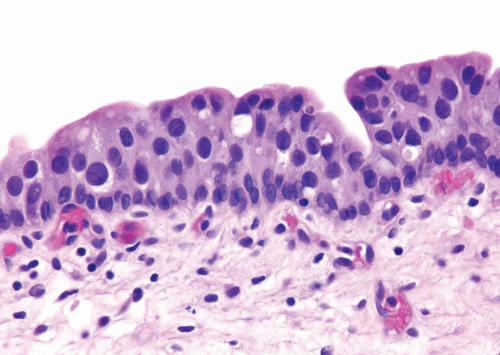

Urothelial Dysplasia

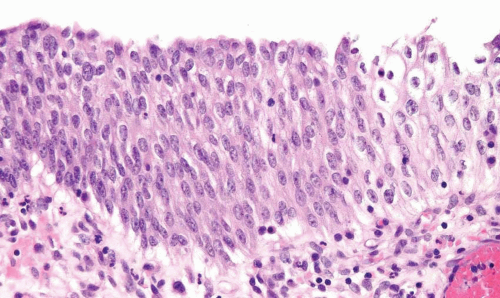

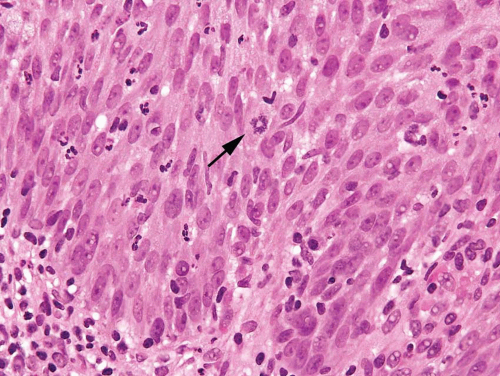

Distinct, appreciable nuclear abnormalities in the urothelium that occur in the absence of inflammation or that appear disproportionate to the amount of inflammation (if present) but are not severe (i.e., falling below the threshold of CIS) may be designated as urothelial dysplasia/low-grade intraurothelial neoplasia (Figs. 2.13, 2.14, 2.15 and 2.16) (efigs 2.30-2.39). It has been proposed that bladder intraepithelial lesions, like intraepithelial lesions of the cervix, be graded on the basis of level of involvement of atypical cells (i.e., mild dysplasia for lesions showing atypia confined to the lower one third, moderate dysplasia for atypia up to the middle third, and so on) (11). However, observations in both animal models and clinical specimens indicate the importance of cytologic features (degree of cytological atypia) rather than histologic pattern (extent of atypia from the basal layer) (12).

FIGURE 2.14 Urothelial dysplasia with loss of polarity, scattered small yet hyperchromatic nuclei and a mitotic figure (arrow). |

FIGURE 2.15 Urothelial dysplasia with scattered hyperchromatic nuclei. Although there is considerable nuclear atypia, the collective features fall short of the diagnosis of CIS. |

FIGURE 2.16 Urothelial dysplasia with scattered, enlarged nuclei. Although there is considerable nuclear atypia, the collective features fall short of the diagnosis of CIS. |

In dysplasia, the thickness of the urothelium is usually normal (three to seven layers) but can be increased or decreased. Flat lesions with a benign cytology and minimal disorder should be considered within the spectrum of “normal” (13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree