| 22 | Fistulas and Postoperative Leakages |

The formation of fistulas or anastomotic leakages can be associated with inflammatory diseases (especially Crohn disease) or therapeutic interventions, which lead to disruption in the continuity of the walls of hollow organs (Tab. 22.1).

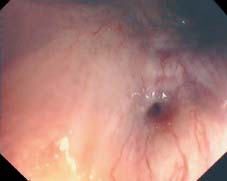

This chapter addresses relevant aspects of these diseases for the colonoscopist. Enterocutaneous fistulas (like the perianal fistula in Fig. 22.1) will not be specifically discussed as they are often complex proctological or surgical problems that would be beyond the scope of this book.

Fistulas

Fistulas

Colovesical fistulas. Colovesical fistulas occur in up to 2% of patients with diverticulitis (references in 2). Other causes include Crohn disease, malignancy, radiation therapy, and trauma. The rate of spontaneous healing is very low (2%). Thus, surgical intervention is usually the therapy of choice, though endoscopic therapy can also be attempted. Fistulas can also occur involving the urethra (Fig. 22.2).

Fistulas |

|

Anastomotic leakage |

|

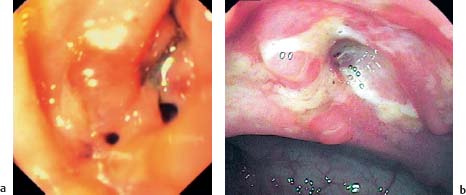

Rectovaginal fistulas. Rectovaginal fistulas (Figs. 22.3–22.5) are also usually due to therapy-related or inflammatory causes. If endoscopic therapy is attempted, it should be performed together with a gynecologist if possible.

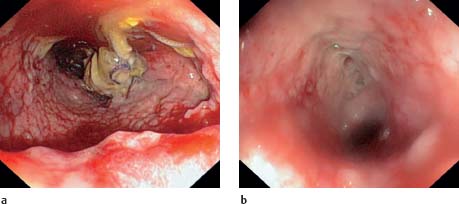

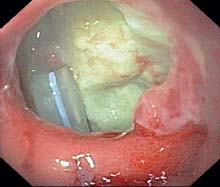

Enteroenteric and enterocutaneous fistulas. There is normally no endoscopic therapy approach for enteroenteric and enterocutaneous fistulas that appear, for example, in Crohn disease (Figs. 22.6, 22.7). Therapy mainly consists of medication and, if necessary, surgical intervention.

Fig. 22.1 Perianal fistula opening in Crohn disease.

Fig. 22.2 Radiation-induced fistula including the urethra (prior rectal carcinoma).

Fig. 22.3 Rectovaginal fistula. The small opening of this fistula was hidden behind a rectal fold and was thus not visible under endoscopy. It was identified at transvaginal cannulation.

Fig. 22.4 Radiation-induced fistula in vagina (prior rectal carcinoma).

Fig. 22.5 Fistula not immediately visible during endoscopy. The fistula was found after administration of a contrast dye in the ulcerlike defect.

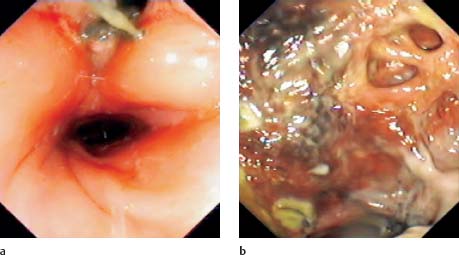

Fig. 22.6 Fistulizing Crohn disease.

a Severe initial episode of Crohn disease. Fistulas were first discovered in the duodenum.

b The other end of the fistulous tract with several openings in the colon; widespread inflammation and ulcers next to the tract.

Fig. 22.7 Tiny fistula opening in an indentation next to the Bauhin valve. The fistula ended after a few centimeters in the terminal ileum, which had massive inflammatory changes.

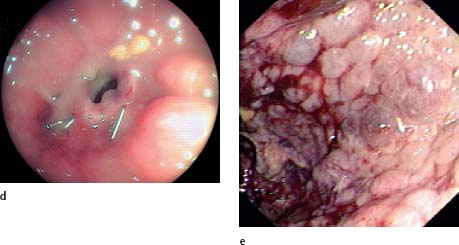

22.1 Varying aspects of anastomotic leakage

22.1 Varying aspects of anastomotic leakage

a, b Development of an anastomotic leak. Circular, covered 7-cm long anastomotic leakage after sigmoid resection with unremarkable clinical signs (a). After four weeks it appears to be healing well (b).

c Anastomotic leak with visible staple near the edge of the fistula; at the lower left the anastomosed region.

d Narrow suture dehiscence; remaining sutures.

e Dehiscence, local drainage is visible, sliding intermittently into the bowel lumen.

f Refractory fistula five months after operation; a recurrent tumor is now visible.

Anastomotic Leakage

Anastomotic Leakage

Definition and prevalence. An anastomotic leakage is any extraluminal extravasation from the region near the anastomosis. It is defined as a complete defect in the bowel wall near the surgical line resulting in communication between intraluminal and extraluminal spaces (7) (  2.1, 22.2, Figs. 22.8, 22.9).

2.1, 22.2, Figs. 22.8, 22.9).

Prevalence figures on anastomotic leakage vary according to localization of the anastomosis and reporting author. According to the literature, leakage rates have decreased considerably in the past 10-20 years. Leakage rates following low anterior rectal resection are reported in the surgical literature at 6-14%.

22.2 Anastomotic leakage with necrotic cavities

22.2 Anastomotic leakage with necrotic cavities

a, b Necrotic cavity with small opening. At the top of the image a relatively small opening to a necrotic cavity (a). Base of the necrotic cavity (b).

c Large horseshoe-shaped dehiscence with sloughed cavity.

d, e Stenosis distal to necrotic cavity. Strictured anastomosis after low anterior rectal resection (d). After dilation, the instrument enters a necrotic cavity. The continuation of the lumen is not visible (e).

f Large dehiscence, recurrent bleeding from the base of the necrotic cavity.

Fig. 22.8 Endoscopic and radiologic views of a fistula.

a Endoscopic view: small fistula opening to a narrow, branching fistula following low anterior rectal resection.

b Using radiologic contrast imaging a Y-shaped fistula tract is visible on the cranial side of the bowel with a small clubshaped retention cavity.

Fig. 22.9 Endoscopic and radiologic views of an anastomotic leak.

a Endoscopic view: ovalshaped anastomotic leak.

b Using radiographic contrast imaging, a small cavity next to a vessel is visible.

Causes. Anastomotic leakages can be caused by local and/or systemic factors. Local factors include suture technique, necrosis, contamination, tissue ischemia, and tissue tension at the site of the anastomosis. Systemic factors include malnutrition, older age, and concomitant diseases associated with delayed healing or tissue hypoxia. Due to the considerable rate of leakage, many surgeons prefer to attach a protective stoma, especially after low anterior rectal resection.

Changes in the appearance of secretion are one clinical sign of an anastomotic leak, especially in situations where local drainage appears to be functioning well. General clinical symptoms are not always present. Nonetheless, postoperative clinical worsening of the patient’s condition should always raise suspicion of an anastomotic leak. Radiologic tests are generally used for primary confirmation of suspected diagnosis (Figs. 22.8, 22.9).

Intra-abdominal anastomotic leaks require surgical management to prevent development of diffuse peritonitis. However, for extraperitoneal low rectal anastomoses, conservative therapy or endoscopic measures are appropriate.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Confirmation of clinical suspicion is initially with radiologic testing, usually by means of conventional contrast radiograph or computed tomography (CT).

Fistulas. Even fistulas that are clearly visible in radiologic tests can often be difficult to identify endoscopically in the colon due to their frequently small openings. Additional procedures are needed to assist in identifying fistulas. For rectovaginal fistulas, for example, cannulation over a wire from the vagina can be helpful (Fig. 22.3). For colovesical fistulas contrast material (e.g., methylene blue) may be useful and can be administered via the installed bladder catheter. The urinary catheter is also absolutely essential for minimizing intravesical pressure to maintain the success of endoscopic fistula closure.

Anastomoses. Anastomoses can already be endoscopically examined in the first few days following operation with an acceptable level of risk and without danger of additional iatrogenic injury. The potential for simultaneous radiographic diagnosis is also an advantage as it can precisely demonstrate any leak or fistula (including cavity) and assist in evaluation before or during endoscopic therapy. It should be noted that unsuccessful endoscopic primary intervention does not compromise later surgical intervention.

Endoscopic Interventions

Endoscopic Interventions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree