Surgical excision is the definitive treatment of urethral diverticulum (UD) and the only reasonable surgical option for treating midurethral and proximal UD. Success depends on proper staging by determining the extent and number of diverticula and attention to surgical technique. This article offers practical guidance in adjusting technique to accommodate commonly encountered difficult clinical scenarios.

Surgical excision is the definitive treatment of urethral diverticulum (UD) and the only reasonable surgical option for treating midurethral and proximal UD. Transvaginal excision of a urethral diverticulum previously has been described, and there has been little variance in technique. The description provided in this article does not differ significantly from previous ones, but it offers some practical guidance in adjusting technique to accommodate commonly encountered difficult clinical scenarios.

Preoperative planning

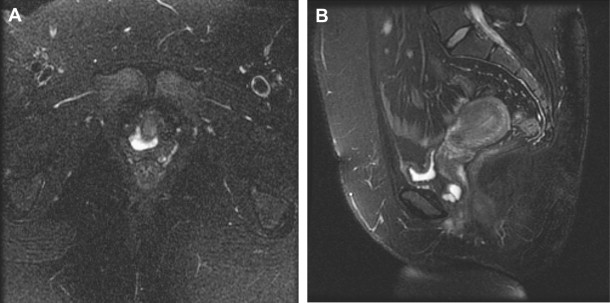

The diagnosis of a UD is made by history, physical examination, and radiography. Positive pressure urethrography with a double balloon catheter largely has been replaced by alternative imaging methods. A voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) and transvaginal ultrasound are readily available and commonly used imaging modalities in cases of UD. The diagnosis and surgical management of UD has been enhanced by the application of MRI to the female pelvis ( Fig. 1 ). In many centers, MRI has become the imaging study of choice for the evaluation of suspected UD. It is favored because of its multiplanar capabilities and tissue-specific high signal to noise. Other benefits of this study are that the patient does not need to be catheterized and does not need to void for the study. The patient is not exposed to ionizing radiation, and the study can be completed within only three breath-hold sequences.

Although urethral imaging protocols may vary between centers, in most cases the study uses high-resolution, fast spin echo and T 2 weighted sequences. On a T 2 weighted image, the diverticulum appears as a hyperintense, well-circumscribed fluid collection that partially or circumferentially surrounds the urethra. The diverticular wall retains a low-signal intensity, and the neck of the diverticulum is seen as a disruption in the circumferential continuity of the diverticular wall. MRI has a sensitivity of 100% for UD, compared with 69% and 70% for VCUG and urethroscopy, respectively. MRI provides better spatial orientation of the proximity of the diverticulum to the bladder neck and improved ability to assess any anterior extension or circumferentiality of the UD compared with VCUG. For these reasons, MRI may be useful for the planning the surgical treatment of recurrent diverticuli or other complex cases.

Paradoxical incontinence, or the loss of urine from the UD with stress maneuvers, resolves with excision of the UD, but concomitant stress urinary incontinence requires additional treatment. In one study, stress urinary incontinence may have been the initial symptom of UD in as many as 62% of female subjects. Preoperative videourodynamics (VUDS) can be helpful in distinguishing paradoxical incontinence from stress urinary incontinence, because leakage can be visualized across the bladder neck versus from the diverticulum. It may identify any detrusor abnormality that is responsible for current lower urinary tract symptoms and could persist after surgery, such as involuntary detrusor contractions. The authors typically perform VUDS before surgery in all patients with incontinence.

After the diagnosis is confirmed radiographically, preoperative preparation should include sterilization of the urine and resolution of any acute suppuration and inflammation of the UD with a short course of appropriate antibiotics.

Transvaginal excision of urethral diverticulum

Step One: Cystourethroscopy

Cystourethroscopy may be done in the office before surgery or delayed until the time of surgery. Definitive localization of the diverticular ostium before surgery is helpful, but many women have considerable pain from the UD. In this circumstance, urethroscopy without anesthesia is painful and unlikely to be an optimal opportunity to thoroughly examine the urethral mucosa. A thorough endoscopic evaluation of the urethra should be made using a 0° or 30° lens and a short-beaked cystoscope (Sasche sheath or 17-Fr sheath). If the diverticulum is visible from the vaginal side, it may be compressed to locate the ostium. Expressed contents of the UD into the urethral lumen may identify its site. Ostia typically are found on the floor of the distal two thirds of the urethra between the 4 and 8 o’clock positions. In many instances, however, the ostium cannot be identified easily. The trigone and ureteral orifices are examined. Any distortion of the orifices or intertrigonal ridge could suggest an ectopic ureterocele that should be investigated further before excision of the vaginal wall mass that previously was suspected to be an UD.

Step Two: Setup, Exposure, and Incision

On leaving the bladder full after cystourethroscopy, a suprapubic catheter may be placed with the aid of a Lowsley retractor ( Fig. 2 ). The suprapubic tube can be used to fill the bladder for postoperative VCUG. If there is any evidence of exstravasation, the suprapubic tube can be left in place for bladder drainage, preventing the need to recatheterize. A 14-Fr Foley catheter is placed in the urethra, and a weighted vaginal speculum is used to retract the posterior vaginal wall.

A Scott ring retractor (Lonestar) provides excellent retraction of the vaginal walls and tissue flaps during UD excision and can be placed before the incision is made. An inverted U-shaped incision is made on the anterior vaginal wall. The apex of the incision is placed just proximal to the meatus. A vaginal wall flap is mobilized off of the periurethral and perivesical fascia to the level of the bladder neck.

Step Three: Development of the Periurethral Flaps

The periurethral fascia is incised transversely with a 15-blade scalpel over the area of the diverticulum ( Fig. 3 ). Flaps are raised proximally and distally with Metzanbaum scissors. Care should be taken to preserve this tissue as best as possible so that it may be used as another layer of closure. In cases of recurrent or large diverticula, the periurethral tissue may be tenuous. Once mobilized, the hooks of the Scott retractor can be placed gently on these flaps for better exposure of the UD.

Step Four: Dissection and Excision of the Diverticular Sac

The diverticular sac is grasped gently with delicate forceps and dissected fully to the level of its neck ( Fig. 4 ). When the sac is freed on all sides, it is amputated. A urethral defect through which the Foley catheter is visible may be created. A classic recommendation for UD excision has been to avoid entering the sac prematurely because such an action may make dissection more difficult; however, when the neck cannot be delineated fully or the sac is too attenuated to avoid its perforation, it may be necessary to open the sac and urethra longitudinally to search for the ostium. The opened floor of the urethra can be examined closely and probed with a lacrimal duct probe, or its equivalent, until the ostia are identified and the affected portion of urethra is excised.

If the sac is extended anteriorly, this portion must be excised, which requires some mobilization of the urethra on its lateral borders to peel off the sac anteriorly. In cases of large UD, complete excision of the sac requires extensive dissection under the trigone, jeopardizing integrity of the ureters and bladder base. In these situations, it may be prudent to leave the most proximal portion of the sac in place.

Step Five: Closure of the Layers

The key to a successful closure is to ensure a watertight suture line under no tension and with no overlapping of suture lines ( Figs. 5 and 6 ). The urethra is closed with a 4-0 running absorbable suture. To ensure watertightness, the clinician can insert an infant feeding tube into the urethra alongside the Foley catheter, inject methylene blue through the tube, and check for any leak of blue fluid from the suture line. The periurethral flaps are closed transversely with a running 3-0 absorbable suture. If these flaps are thin, a Martius flap can be used to cover the urethral closure and provide another layer of vascularized tissue. The vaginal incision is closed with a running 2-0 absorbable suture. Other indications for use of a Martius graft include the following:

Fibrotic and scarred tissues

Absence of periurethral fascia

Recurrent diverticula

Complicated repair (eg, circumferential diverticulum).