Pelvic floor dysfunction and fecal incontinence is a common and debilitating condition in women, particularly as women age, and often goes under-reported to health care providers. It is important for providers to ask patients about possible symptoms. An algorithm for evaluation and treatment is presented. Current and future therapies are described and discussed.

Key points

- •

Pelvic floor dysfunction, which includes pelvic organ prolapse, urinary incontinence, and fecal incontinence (FI), is very common among parous women.

- •

FI is also common, particularly among older women, can be socially isolating, and often goes under-reported to their health care providers. Physicians should actively ask their patients about these symptoms.

- •

FI is commonly associated with older age, change in bowel habits (typically loose and/or frequent stools, fecal urgency), and debility. FI is common in institutionalized patients.

- •

Treatment of FI initially involves a combination of dietary and lifestyle modifications, medications, and biofeedback training. If conservative methods fail to improve FI symptoms, then other interventions can be considered, including nerve stimulation, anal sphincter augmentation, and surgical options.

Introduction/epidemiology

Pelvic floor dysfunction, which includes urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence (FI), and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), affects 25% or more of women. These disorders will become more prevalent with an aging population. In 2008, there were 38.6 million and 5.4 million Americans aged 65 years and 85 years and older, respectively. In 2050, the 65-year-old and 85-year-old and older segments of the population will more than double to 88.5 million and 19 million, respectively. With increasing age, women comprise a higher percentage of the population among all older age groups: 54% in those aged 65 to 69 years, 69% of those aged 85 to 89 years, and 80% of those aged 95 to 99 years. Wu and colleagues estimated the future prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in women using the US Census Bureau population projections from 2010 to 2050. FI is expected to have the largest increase at 59% (10.6 million to 16.8 million affected women). They estimated that the number of women with urinary incontinence will increase 55% from 18.3 million in 2010 to 28.4 million in 2050, whereas POP will increase 46% from 3.3 million to 4.9 million from 2010 to 2050. This article focuses largely on fecal incontinence, but discusses these other pelvic floor disorders because they are pertinent in the evaluation and work-up of FI.

FI, sometimes referred to as accidental bowel leakage, is defined as the involuntary loss or passage of solid or liquid stool in patients with a developmental age greater than 4 years. However, the definition can vary based on consistency of stools and frequency or duration of symptoms. FI does not include flatal incontinence or fecal soilage. Anal incontinence comprises both liquid and stool incontinence along with gas incontinence. Fecal soilage is the staining or streaking of underwear with fecal material or mucus.

The prevalence of FI in women ranges from 2% to 25%, but this varies based on definition used, age, and living situation (independently living vs nursing home). The prevalence of FI increases from 2.6% in young women (aged 20–29 years) to 15.3% by age 70 years or older. In addition, 88% of women with FI develop their symptoms after age 40 years. Women living in nursing homes or other institutionalized settings are at high risk for FI, with a prevalence among this population between 14% and 47%.

The reported prevalence of FI likely underestimates the true prevalence because FI is significantly under-reported to physicians. Patients are often reluctant to discuss their symptoms because it is embarrassing. In the recent Mature Women’s Health Study, Brown and colleagues found that two-thirds of women with FI do not seek care for their symptoms even though 40% of them had symptoms severe enough to affect their quality of life. However, physicians also bear the burden for the underdiagnosis of FI. Dunivan and colleagues showed that practitioners routinely fail to inquire about FI during patient visits.

Quality of life can be significantly affected in patients with FI, resulting in patient embarrassment, psychological stress, social isolation, and job loss, and it is the second leading cause of placement in a skilled nursing facility ( Box 1 ).

They say man has succeeded where the animals fail because of the clever use of his hands, yet when compared to the hands, the sphincter ani is far superior. If you place into your cupped hands a mixture of fluid, solid, and gas and then through an opening at the bottom, try to let only the gas escape, you will fail. Yet the sphincter can do it. The sphincter apparently can differentiate between solid, fluid, and gas. It apparently can tell whether its owner is alone or with someone, whether standing up or sitting down, whether its owner has his pants on or off. No other muscle of the body is such a protector of the dignity of man, yet so ready to come to his relief.

Introduction/epidemiology

Pelvic floor dysfunction, which includes urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence (FI), and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), affects 25% or more of women. These disorders will become more prevalent with an aging population. In 2008, there were 38.6 million and 5.4 million Americans aged 65 years and 85 years and older, respectively. In 2050, the 65-year-old and 85-year-old and older segments of the population will more than double to 88.5 million and 19 million, respectively. With increasing age, women comprise a higher percentage of the population among all older age groups: 54% in those aged 65 to 69 years, 69% of those aged 85 to 89 years, and 80% of those aged 95 to 99 years. Wu and colleagues estimated the future prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in women using the US Census Bureau population projections from 2010 to 2050. FI is expected to have the largest increase at 59% (10.6 million to 16.8 million affected women). They estimated that the number of women with urinary incontinence will increase 55% from 18.3 million in 2010 to 28.4 million in 2050, whereas POP will increase 46% from 3.3 million to 4.9 million from 2010 to 2050. This article focuses largely on fecal incontinence, but discusses these other pelvic floor disorders because they are pertinent in the evaluation and work-up of FI.

FI, sometimes referred to as accidental bowel leakage, is defined as the involuntary loss or passage of solid or liquid stool in patients with a developmental age greater than 4 years. However, the definition can vary based on consistency of stools and frequency or duration of symptoms. FI does not include flatal incontinence or fecal soilage. Anal incontinence comprises both liquid and stool incontinence along with gas incontinence. Fecal soilage is the staining or streaking of underwear with fecal material or mucus.

The prevalence of FI in women ranges from 2% to 25%, but this varies based on definition used, age, and living situation (independently living vs nursing home). The prevalence of FI increases from 2.6% in young women (aged 20–29 years) to 15.3% by age 70 years or older. In addition, 88% of women with FI develop their symptoms after age 40 years. Women living in nursing homes or other institutionalized settings are at high risk for FI, with a prevalence among this population between 14% and 47%.

The reported prevalence of FI likely underestimates the true prevalence because FI is significantly under-reported to physicians. Patients are often reluctant to discuss their symptoms because it is embarrassing. In the recent Mature Women’s Health Study, Brown and colleagues found that two-thirds of women with FI do not seek care for their symptoms even though 40% of them had symptoms severe enough to affect their quality of life. However, physicians also bear the burden for the underdiagnosis of FI. Dunivan and colleagues showed that practitioners routinely fail to inquire about FI during patient visits.

Quality of life can be significantly affected in patients with FI, resulting in patient embarrassment, psychological stress, social isolation, and job loss, and it is the second leading cause of placement in a skilled nursing facility ( Box 1 ).

They say man has succeeded where the animals fail because of the clever use of his hands, yet when compared to the hands, the sphincter ani is far superior. If you place into your cupped hands a mixture of fluid, solid, and gas and then through an opening at the bottom, try to let only the gas escape, you will fail. Yet the sphincter can do it. The sphincter apparently can differentiate between solid, fluid, and gas. It apparently can tell whether its owner is alone or with someone, whether standing up or sitting down, whether its owner has his pants on or off. No other muscle of the body is such a protector of the dignity of man, yet so ready to come to his relief.

Pathophysiology

Continence is a complex process involving the internal and external anal sphincters, compliant rectum, puborectalis muscle, neurologically intact anal sphincter complex, and functional pelvic floor muscles. FI can develop when bowel motility is altered (either diarrhea or constipation), or from weakening of the anal sphincter muscles, rectal inflammation or other causes of poor rectal compliance, rectal sensory abnormalities, or dysfunction of the pelvic floor musculature. In 80% of patients there is more than 1 pathophysiologic factor that causes FI. There are multiple physiologic factors associated with aging. Both sphincters can be affected with fibrosis and thickening leading to decreased resting tone, with thinning of the external anal sphincter producing a weak squeeze pressure. In addition, decreased rectal sensation, rectal compliance, and rectal capacity all cause impairment of the colorectal sensorimotor function and impaired rectal reservoir function.

Risk factors

Multiple studies have described risk factors for FI. These risk factors are listed in Box 2 . Although the impact of most of these risk factors is debatable, the major risk factors for FI in women seem to be advanced age, alterations in bowel movements, and institutionalization. The major gastrointestinal symptom strongly associated with FI is diarrhea, and any disease that can cause loose/watery stools or frequent bowel movements (more than 21 stools per week) can lead to FI. However, a portion of these cases may be caused by underlying constipation with or without fecal impaction, causing overflow diarrhea. The mechanism of incontinence with diarrhea is likely multifactorial, but it may be caused by increased difficulty retaining loose or watery stool, overwhelming the anal sphincter with high volumes delivered to the rectum in a short interval of time, reflex inhibition of the internal anal sphincter (IAS), and/or interactions between the consistency of the stool and sphincter defects. Other major risk factors include concurrent stress urinary incontinence, prior vaginal delivery with forceps or stitches, rectal urgency, and multiple chronic comorbidities.

Patient characteristics

Increased age

Female gender

Current smoking

Obesity

Institutionalization

Gastrointestinal factors

Loose or watery stools

Frequent bowel movements (>21/wk)

Rectal urgency

Functional bowel disorders

Inflammatory bowel disease

Fecal impaction/severe constipation with overflow incontinence

Rectocele

Obstetric history factors

Multiparity

Sphincter laceration/episiotomy

Prolonged second stage of labor

Vacuum extraction

Vaginal delivery with forceps

Other medical comorbidities

Urinary incontinence

Multiple chronic illnesses

Debility

Dementia

Dietary intolerances/dietary factors

Enteral tube feeding

Medication side effects

Anxiety/depression

Diabetes

Neurologic disease/prior stroke

History of pelvic radiation

Effects of prior surgery

Hysterectomy

Cholecystectomy

Anal sphincterotomy

Hemorrhoidectomy

Colectomy with ileoanal pouch anastomosis

Evaluation

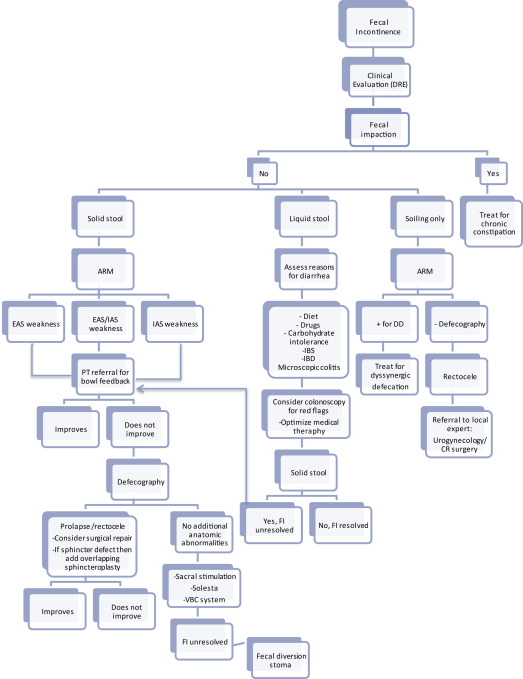

An algorithm for the evaluation and management of FI is shown in Fig. 1 . The first step in this process involves obtaining a detailed history and examination, including digital rectal examination to assess for sphincter defects, rectal tone, and fecal impaction. If fecal impaction is present, then treatment should focus on the management of constipation. The clinicians must determine whether the patient has symptoms of fecal soilage or of true incontinence. If incontinent, is it solid or liquid stool? Current medications should be reviewed to identify anything that may exacerbate FI ( Table 1 ). Also consider constipating medications as a cause for overflow diarrhea/overflow incontinence.

| Drugs | Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Nitrates, CCB, BB, sildenafil, SSRI | Reduce sphincter tone |

| Glyceryl trinitrate ointment, diltiazem gel, bethanechol cream, botulinum toxin A injection | Reduce sphincter tone via application of topical medications to the anus |

| Antibiotics, laxatives, metformin, orlistat, SSRI, magnesium-containing antacids, digoxin, PPI | Cause loose stools or diarrhea |

| Benzodiazepines, SSRI, antipsychotics | Relaxant, hypnotic |

Fecal Soilage

The initial work-up for women with fecal soilage only should include anorectal manometry (ARM) to evaluate for dyssynergic defecation. If present, then the patient should be referred to physical therapy (PT) for biofeedback training (BFT) and consideration of the nonpharmacologic treatment options described later (see Fig. 1 ). Postvoid enemas can be considered to remove residual stool in the rectum and anal canal.

Liquid Stool Incontinence

If incontinent of liquid stool only, then evaluation for causes of diarrhea should be pursued, including possible colonoscopy, and treatment tailored to the cause. Common causes of diarrhea include medication side effects, diet, carbohydrate intolerance, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, microscopic colitis, bile acid malabsorption, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease, and autonomic dysfunction. Management generally focuses on dietary and lifestyle interventions as well as the antidiarrheal pharmacologic options described later (see Fig. 1 ), but varies based on the cause.

Solid Stool Incontinence

The approach for patients with solid stool incontinence should begin with ARM to evaluate for weakness in the IAS or external anal sphincter or both. If present, then referral to PT for BFT is appropriate. If incontinence does not improve, then functional imaging with either fluoroscopic defecography, dynamic cystocolpoproctography, or MRI defecography should be performed to evaluate for concomitant anatomic abnormalities. If POP or rectocele is identified, then referral for surgical intervention should be considered, with or without sphincter repair as indicated. If no anatomic abnormalities are identified, then minimally invasive approaches, such as injectable bulking agents, sacral nerve stimulator, or vaginal bowel control system, can be attempted. If these methods fail, then definitive surgical intervention, including fecal diversion, can be considered (see Fig. 1 ). If surgical options are being considered, then first perform endoscopic ultrasonography or transanal ultrasonography to assess sphincter integrity.

Treatment of fecal incontinence

Treatment options for FI vary from noninvasive strategies such as dietary and lifestyle changes, PT with BFT, and pharmacologic agents, to minimally invasive options such as nerve stimulation, sphincter augmentation methods with injectable bulking agents or radiofrequency energy, and bowel control systems, to more invasive surgical interventions of sphincteroplasty, sphincter repair, and fecal diversion surgery. These options are listed in Table 2 .

| Noninvasive Interventions | Minimally Invasive Procedures | Surgical |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary modification (increase dietary fiber intake; avoid common trigger foods such caffeine, dairy, high-fat foods) | Sphincter augmentation with injectable bulking agents or radiofrequency energy | Sphincteroplasty |

| Modifiable behavioral risks (weight loss, smoking cessation, increased exercise) | Sacral nerve stimulation | Artificial anal sphincter a |

| Pharmacologic therapies | Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation | Muscle transposition |

| Anal wicking | Eclipse System b | Diversion surgery |

| Increased fiber/bulking agents | Magnetic anal sphincter b | |

| Bowel regimen (if constipated) | TOPAS system b | |

| PT with BFT |

a Technique largely abandoned because of severe adverse events, including sphincter erosion.

b Technique still investigational or not yet widely available.

Dietary and Lifestyle Modification

Potentially modifiable risk factors, such as obesity, inactivity, and smoking, should be addressed. Weight loss has been shown to improve FI in obese women. Behavioral techniques for FI can be implemented, including bowel-retraining techniques such as pausing to perform Kegel exercises rather than rushing to the bathroom, which increases abdominal wall strength and reduces the focus on the pelvic floor, aiding in continence. Toileting strategies such as performing a few Kegel exercises between wiping can also help improve episodes of incontinence.

Some patients may also benefit from vaginal splinting and/or techniques such as anal wicking with a cotton ball or rectal enemas to prevent fecal soilage or mild incontinence. Anal wicking is the technique of placing a long piece of cotton or a cotton ball shaped into a wick between the buttocks, resting directly on the anus so that mild seepage of fecal material is contained. Vaginal splinting is discussed in further detail later.

Dietary interventions can focus on foods that are known to cause loose stools or urgency. Avoidance of common triggers such as caffeine, dairy products, or high-fat foods can be helpful. Dietary fiber and/or stool bulking agents, such as psyllium, can improve symptoms of FI. A cross-sectional survey of elderly Korean women showed that those with the lowest weekly intake of dietary fiber had a 2.66-fold increased likelihood of having FI (overall prevalence of FI in this population, 15.5%). Bliss and colleagues, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, showed a significant decrease in reported symptoms of FI in patients receiving 1 month of daily fiber supplementation with either psyllium (with 49% of stools at baseline associated with FI to 17% with psyllium) or gum arabic (with 66% of stools at baseline associated with FI to 18% with gum arabic) compared with placebo. Only 1 study has assessed the efficacy of a fiber supplement compared with a medication in a randomized fashion. Markland and colleagues recently conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study that compared daily loperamide versus psyllium in the treatment of FI. Eighty adults (68% male) were given either daily loperamide (with a concurrent placebo powder) or psyllium powder (with a concurrent placebo pill) for 4 weeks, followed by a 2-week wash-out period, then another 4 weeks of the opposite treatment in the crossover arm. Both groups showed improvement in number of FI episodes per week and quality of life, but there was no difference between loperamide and psyllium among these end points. Loperamide was associated with higher rates of constipation than psyllium, but no other adverse effects were noted.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Medications that target causes of diarrhea should be considered. Common medications that can be effective for loose stools and FI are listed in Table 3 . They include antidiarrheal/antimotility agents, stool bulking agents, bile acid resins, tricyclic antidepressants, and others that can enhance the anal sphincter tone.

| Mechanism of Action | Medications |

|---|---|

| Stool bulking agents | Psyllium, methylcellulose, gum arabic |

| Antidiarrheal/antimotility | Loperamide, diphenoxylate/atropine, codeine |

| Bile acid resins | Cholestyramine, colestipol, colesevelam |

| Bacterial overgrowth | Various antibiotics |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Nortriptyline, amitriptyline |

| Enhancement of anal sphincter tone | Phenylepinephrine gel, sodium valproate, zinc-aluminum ointment, L-erythro methoxamine gel |

| Barrier creams | Zinc oxide, Calmoseptine ointment, Alkagin powder, Aquaphor ointment |

In a recent Cochrane Review, Omar and Alexander identified only 16 trials evaluating the efficacy of various medications for the treatment of FI. This review included 7 antidiarrheal medication trials, 6 trials for medications that enhance the anal sphincter tone (phenylephrine gel or sodium valproate), 1 trial of zinc-aluminum ointment, and 2 trials of laxatives in patients with FI caused by constipation and overflow diarrhea. There were no included studies of medications compared with other treatment modalities. Overall, although these data are limited, all of these studies showed improvement in FI but most reported side effects (only zinc-aluminum ointment had no reported adverse effects). There were insufficient data to recommend one type of medication rather than another.

Some patients may also benefit from perianal barrier creams to prevent skin excoriation and incontinence-associated dermatitis, or from techniques such as anal wicking with a cotton ball, or the routine use of rectal enemas to prevent fecal soilage or mild incontinence. The incidence of incontinence-associated perianal dermatitis is 41% among community-dwelling adults with FI. This rate is mildly associated with severity of FI, but not with age, gender, or concurrent urinary incontinence.

Biofeedback Therapy

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) alone has been shown to be effective for the treatment of urinary incontinence, but outcomes for FI seem to be improved with the addition of BFT in uncontrolled studies. However, a randomized trial of biofeedback compared with either PFMT or advice alone showed no additional benefit from BFT. BFT is a form of PT that uses electronic instrumentation to monitor specific, often unconscious, physiologic activities, and then uses a visual or auditory signal to provide the information as feedback to the patient. Although biofeedback techniques vary, the methods, which may be used independently or in combination, include rectal sensory training and compliance, strength and endurance training of the pelvic floor and anal sphincter, and coordination training of the anal sphincter. In addition to pelvic floor exercises, biofeedback instrument modalities include electrical stimulation, rectal distention balloons, surface and/or intra-anal electromyography (EMG), manometric pressures, and transanal ultrasonography. The success of BFT is variable, from 0% to 80%. A multicenter study found that success is best achieved if biofeedback uses a combination of EMG, electrical stimulation, and a long duration of treatment (>3 months). In a recent Cochrane Review, Norton and Cody did not find any evidence that specific types of biofeedback or exercise were more beneficial than others, but that BFT or electrical stimulation is more efficacious than PFMT alone in patients who have failed to respond to other conservative measures.

Anal Sphincter Augmentation

Two minimally invasive options exist that augment the native anal sphincter, including injectable bulking agents and radiofrequency energy. These methods can be considered in patients with mild to moderate FI, no anatomic anal sphincter abnormalities, and who have failed the conservative medical therapies described earlier.

Injectable bulking agents

The current most common injectable medication is dextranomer with hyaluronic acid (NASHA/Dx; Solesta, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Raleigh, NC), although other injectable materials can be used (collagen, silicone, autologous fat, glutaraldehyde, and carbon-coated beads, among others ). NASHA/Dx is a biocompatible injectable gel consisting of dextranomer microspheres stabilized in hyaluronic acid that is injected submucosally in all 4 quadrants of the anal sphincter just proximally to the dentate line. This procedure is performed via anoscope, and can be performed with only local anesthesia. A multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled study found that approximately half of their patients receiving NASHA/Dx had a greater than 50% reduction in the number of FI events compared with 30% of patients with the sham injections (odds ratio, 2.36; confidence interval, 1.24–4.27; P = .0089). An earlier trial showed similar efficacy results that lasted at least 12 months after treatment. Frequent adverse events have been reported with the use of NASHA/Dx, including serious rare complications of rectal and prostate abscesses.

Radiofrequency energy

The SECCA procedure (Curon Medical, Inc, Fremont, CA) delivers radiofrequency energy to the IAS in order to stimulate increased collagen deposition in the IAS and improve continence and sphincter tone. Through the use of a commercially available device, temperature-controlled radiofrequency energy (RFE) is applied multiple times to all 4 quadrants of the anal sphincter. This procedure is typically performed under conscious sedation in an endoscopy suite or operating room. A recent review of the SECCA procedure found only 11 studies for a total of 220 patients, but did find that SECCA may be useful for well-selected patients (those with adequate muscle mass and collagen in the sphincter at baseline) to reduce the number of incontinence episodes and improve quality of life. However, the results of SECCA have been variable, including a recent small prospective cohort trial that failed to show any significant clinical response or durability up to 3 years following the procedure in most of their patients. In addition, Lam and colleagues failed to show any changes in anorectal pressures or rectal compliance, as measured by rectal endoscopic ultrasonography and anorectal manometry. One advantage is that RFE may lead to fewer adverse events compared with other types of procedures, such as injectable bulking medications, nerve stimulation, and surgery.

Nerve Stimulation

In patients with moderate to severe FI who have failed to respond to more conservative measures, nerve stimulation can be considered. Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) has been used for the last 20 years, whereas percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) for the treatment of FI was developed more recently.

Sacral nerve stimulation

SNS (Interstim, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) is thought to improve FI by chronically stimulating the sacral nerves, and therefore the corresponding muscles, by applying a low-voltage electrical current via an implanted electrode through the corresponding sacral foramen. Most commonly, SNS placement is performed in a 2-stage process. During the first stage, a tined electrode lead is placed parallel to the sacral nerve through the S3 sacral foramen and stimulated with a percutaneous nerve stimulator for a 1-week to 2-week trial period. If a reduction in FI symptoms is seen, then a permanent implanted nerve stimulator is implanted in the buttock and connected to the tined lead. The implanted device is then programmed to the individual’s response pattern.

A recent Cochrane Review found that SNS can be effective for improving FI. In multiple small crossover studies, when the SNS device is turned on, episodes of FI can improve from 59% to 88% compared with conventional medical therapy. One study failed to show any improvement in episodes of FI when the device was on versus off. The improvement in FI symptoms seems to be durable, with Hull and colleagues reporting 89% of patients reporting continued significant reduction in weekly episodes of FI at 5 years postimplantation compared with baseline (mean 9.1 episodes of FI per week at baseline compared with 1.7 per week at 5 years), and about a third of patients had complete resolution of symptoms. Multiple studies have shown impressive results with SNS even in patients with known sphincter defects, and that the degree of defect does not affect results.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation

The tibial nerve shares nerve fibers with the sacral nerve. PTNS is a technique whereby the posterior tibial nerve is stimulated with a needle. PTNS is performed weekly in the outpatient setting for 12 weeks, for about 30 minutes per session. The major advantage compared with SNS is that it is much less invasive and does not require the placement of an implantable device. Stimulation of the tibial nerve is comparable with SNS in the treatment of urinary incontinence, and initial studies for the treatment of FI have been promising. Thin and colleagues showed that PTNS and SNS had comparable results in the treatment of FI, at least in the short term. However, when PTNS was compared with a sham electrical stimulation procedure, no difference was seen in FI clinical outcomes between the two groups. Further confirmatory studies will determine its utility in FI treatment.

Surgical Options

Options for surgical intervention are considered when more conservative therapies have failed. Surgical options include sphincteroplasty, muscle transposition, antegrade continence enema, and fecal diversion.

Sphincteroplasty

Sphincteroplasty, or repair of the anal sphincter, commonly using an anterior overlapping technique, has long been used to treat FI caused by external anal sphincter injury when conservative therapies have failed. Most women with FI caused by anal sphincter injury have a history of vaginal delivery, and the most common risk factors include multiple vaginal deliveries, need for vaginal instrumentation during labor, third-degree or fourth-degree tear, pudendal nerve injury, and failed prior sphincteroplasty. Short-term outcomes for sphincteroplasty are generally much better than long-term outcomes. In the short term, the median rate of either good or excellent fecal continence with sphincteroplasty is 70%, ranging from 30% to 83%. However, numerous recent long-term studies have shown less promising results for the durability of the procedure. Long-term continence decreases to 0% to 60% in most studies. Although many of these studies concluded that advanced age at the time of the surgery was a risk factor for long-term failure, a recent systematic review did not find any consistent factors, including age, that were predictive for failure. In addition, a recent large retrospective review of 321 women did not show any significant difference in long-term severity of FI, quality of life, or postoperative satisfaction between younger versus older women.

Muscle transposition

Muscle transposition is another surgical technique that was used more commonly in the past for medically refractory FI, but is rarely used now because of the high rate of adverse events associated with this procedure and the availability of other less invasive but equally effective treatment options. This technique, which is now typically only performed at highly specialized surgical centers, involves the surgical harvesting of functional skeletal muscle with either the gluteus maximus or gracilis muscle, and wrapping around the nonfunctional anal sphincter complex to create a new sphincter in vivo. Graciloplasty can be either unstimulated (adynamic) or stimulated (dynamic). The unstimulated technique relies on patients to learn how to voluntarily contract the muscle to aid in continence, whereas the stimulated technique has the addition of an implanted neuromodulator to help keep the skeletal muscles tonically contracted, allowing superior results. Outcomes are good with muscle transposition, with a reported success of 60% to 75%, but postsurgical complications are common. These complications include surgical site infection, rectal pain, rectal injury, stimulator malfunction, and device erosion, and the prevalence of postsurgical obstructive constipation symptoms can be as high as 50%.

Antegrade continence enema

Use of antegrade continence enemas (ACE) for the treatment of FI has long been described and used in the pediatric population with good success. However, it is rarely used in the adult population. This procedure involves the creation of a stoma from the appendix, terminal ileum, or cecum, or other type of proximal access point (such as gastrostomy tube placement into cecum), instilling water or enema solution via this access point, and allowing fecal material to be flushed from the colon in an antegrade manner, alleviating symptoms of both FI and constipation. A recent systematic review found that most adults (47%–100%) were still performing ACE at 6 to 55 months’ follow-up, and at least a third of patients achieved full continence.

Fecal diversion

Creation of an end colostomy or ileostomy for fecal diversion can be considered when all other modalities of treatment have failed, or with specific rare indications such as severe neurogenic incontinence, complete pelvic floor denervation, severe perianal trauma, severe radiation-induced incontinence, or significant physical or mental incapacitation. This surgical approach is aggressive, but for some patients can dramatically improve quality of life compared with those dealing with fecal incontinence. Norton and colleagues found that 83% of patients who had undergone colostomy placement for their FI had little or no restriction in their life caused by their ostomy, and that 84% would choose to have the stoma placement again.

Potential Future Treatments

Future FI treatment strategies that may soon (or not so soon) become available include a vaginal bowel control system called the Eclipse system, magnetic anal sphincter, Trans-obturator Post-Anal Sling (TOPAS) pelvic floor repair system, and autologous cell or stem cell transplant.

The eclipse system

The Eclipse System (Pelvalon Inc, Sunnyvale, CA) is a vaginally placed device for the treatment of FI that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in early 2015. It is fitted like a vaginal pessary, and has a posteriorly directed inflatable balloon. When the balloon is inflated, it occludes the rectal vault and prevents incontinence. However, for defecation, the patient is then able to temporarily deflate the system. The major advantages of this device are that it is easily reversible, dynamically controlled by the patient, and low risk. In a study of 61 women, Richter and colleagues reported that 86% of women, in a per-protocol analysis considered bowel symptoms to be very much better or much better after 1 month of use, which was still stable at 3 months, and quality of life was significantly improved. In that study, there were no serious adverse events. The most common side effect was cramping or discomfort, typically during fitting.

Magnetic anal sphincter

An investigational device called the Magnetic Anal Sphincter (MAS; Fenix, Torax Medical Inc, Shoreline, MN) is a small, flexible band of interlinked titanium beads with magnetic cores. It is surgically implanted around the external anal sphincter and functions to reinforce and improve competence of the sphincter. The magnets separate with Valsalva maneuver, allowing defecation.

Lehur and colleagues first described their experiences with, and results of, MAS in 2010. Fourteen women, all of whom had previously failed other treatments, were implanted with MAS. Only 5 of 14 were followed for at least 6 months, but, among this group, they reported a 91% mean reduction in average weekly FI episodes and had significant improvement in quality of life. Two of the 14 patients had the device explanted because of infection, and 1 had spontaneous passage of the device. Other observed adverse events included bleeding, pain, and obstructed defecation.

Another study by Pakravan and colleagues described the results of 18 patients implanted with MAS for FI, followed up to 2 years (mean follow-up, 607 days). One of the 18 patients had an intraoperative rectal perforation, and the procedure was aborted. Of the 17 remaining, 76% of patients showed at least a 50% reduction in number of weekly FI events. None of the patients required explantation, but 29% had pain and/or swelling.

In the short term, MAS performs comparably with artificial bowel sphincters. However, in a 10-year follow-up study, artificial bowel sphincters had high complication rates, typically caused by risk for infection. Fifty percent of the patients with artificial bowel sphincters have required explantation or revision because of device malfunction or infection.

TOPAS pelvic floor repair system

The TOPAS pelvic floor repair system (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN) is an investigational device consisting of a single-use, self-affixing polypropylene mesh sling. It is intended to reinforce soft tissues in the pelvic floor where there are areas of weakness in the gastrointestinal and gynecologic anatomic structures. The center point of the mesh is surgically placed posterior to the anorectum and is brought out through both obturator foramen, similar to a transobturator urinary sling.

Initial data by Rosenblatt and colleagues describe the results of 29 women with FI that had failed at least 1 prior therapy, followed up to 2 years postplacement. Fifty-five percent of the women reported treatment success, which was defined as at least a 50% reduction in the number of FI episodes per week. Improvements in continence (as measured by the Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score) and quality of life (as measured by the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life) were sustainable through the 2-year follow-up period. The most common adverse events were de novo urinary incontinence (n = 6 of 29), worsening FI (n = 2 of 29), and constipation (n = 2 of 29). No device erosions or extrusions were reported. A larger, multicenter trial by Fenner and colleagues involving 152 women with similar end points showed efficacy in 69.1% and complete continence in 19% of women. The TOPAS system is not yet commercially available, but is currently under investigation.

Cell transplant

Injection of autologous skeletal muscle cells into the external anal sphincter to stimulate muscle growth and regeneration in humans has been described, and mesenteric stem cell transplant has been described in animal models. Pathi and colleagues showed that direct injection of mesenteric stem cells into injured rat anal sphincters stimulated increased contractility. Frudinger and colleagues followed 10 women with obstetric-related anal sphincter injury over a 5-year follow-up period. They harvested autologous skeletal muscle–derived cells from each patient’s pectoralis muscle and directly injected these cells into the external anal sphincter defect. Improvement in continence and quality of life was seen, which was sustainable for the duration of the follow-up period. Although there may be promise for this method in the future, more research into the utility of autologous or stem cell transplant must be undertaken before it becomes more widely used.

Pyloric valve transplant

In 2011, Goldsmith and Chandra described a novel surgical technique in humans whereby a poorly functional anal sphincter complex is recreated by transplantation of an autologous pyloric valve. This procedure is described in patients with end-stage FI as an alternative to permanent end colostomy. Chandra and colleagues showed better continence outcomes when the pyloric valve was used to augment the native anal sphincter rather than replace it, although there was improvement in both groups.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree