Reoperation mandatory

External drainage

End-tube hepatodochostomy or choledochostomy

Reoperation not always necessary

T-tube or stent with limb beneath injury

In patients with multiple intra-abdominal injuries, profound hypotension, and intraoperative “metabolic failure,” the surgeon’s goals are control of hemorrhage from major abdominal vascular structures, the mesentery, and the porta hepatis; control of oozing from the retroperitoneum, pelvis, and solid organ injuries other than the spleen by insertion of packs; removal, ligation, or stapling off of segments of the bowel containing multiple perforations; and rapid silo or vacuum-assisted coverage of the open abdomen. The injury to the bile duct is ignored in such patients because survival is unclear, and early reoperation will be necessary anyway to remove the intra-abdominal packs. These considerations are illustrated by the case report depicted in Figs. 15.1 and 15.2.

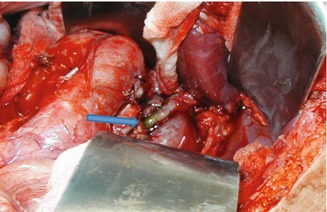

Fig. 15.1

This patient had a motor-vehicle crash and presented to the emergency department in hemodynamic instability. Laparotomy demonstrated a large amount of hemoperitoneum, grade IV crush of the right lobe of liver, crush injury of the second portion of the duodenum and the head of the pancreas, skeletonization without rupture of portal vein, and a complete avulsion injury of the common bile duct (CBD) from the duodenum (arrow). Hemostasis was secured by debridement-resection of liver and perihepatic packing. The common duct was ligated above and below the avulsion

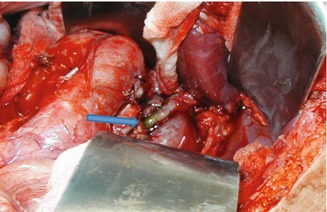

Fig. 15.2

Relaparotomy after 24 h of resuscitation showed the following: bleeding was controlled, but the lower half of the CBD had avascular necrosis (arrow), necessitating resection and a higher anastomosis between the common hepatic duct and the jejunum. This necrosis should be anticipated in such injuries because of the segmental blood supply of the common duct arising from the gastroduodenal artery and ascending up the duct at 3 and 9 o’clock positions

When the patient’s condition is more stable but operation has been prolonged and a state of “metabolic failure” appears likely, several options short of formal repair are possible to control the leakage of bile. Included among these are insertion of a closed suction drain near the ductal injury, insertion of a red rubber tube into the proximal end of a transected hepatic or common bile duct, and insertion of a T-tube. Both the insertion of a Jackson-Pratt drain and the creation of an end-tube hepatodochostomy or choledochostomy are best followed by early reoperation for definitive repair when the patient’s condition is stable. The ideal insertion site for a T-tube is into a partial transection. With partial transection of a right or left hepatic duct, a small T-tube may be inserted into the common hepatic duct with a long proximal limb passing through the lacerated or partially transected area. Even without suture repair, reoperation may be avoided in such a patient, depending on the future severity of the stricture at the site of injury.

Options for Repair in Patients Who Are Hemodynamically Stable (Table 15.2)

Table 15.2

Options for repair in patients who are hemodynamically stable

Avulsion of cystic duct or laceration |

Cystic duct or gallbladder pedicle |

Heineke-Mikulicz repair |

Primary repair with absorbable suture |

Transection without loss of tissue |

End-to-end anastomosis |

Choledochoduodenostomy |

Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy |

Extensive defect in the wall |

Mucosal onlay patch |

Serosal onlay patch |

Vein patcha |

Prosthetic patcha |

Segmental loss of ductal tissue |

Formal reconstruction |

Cholecystoduodenostomy or cholecystojejunostomy (loop or Roux-en-Y) |

Choledochoduodenostomy |

Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy or hepatodochojejunostomy (hepaticojejunostomy) |

Roux-en-Y hepatoportal jejunostomy |

Ligation or resection |

Ligation of right or left hepatic duct |

Hepatic resection |

Whipple procedure |

Definitive repair or resection followed by repair is performed in a patient whose condition is stable, with the option chosen based on the extent of the ductal injury. The spectrum of ductal injuries includes avulsion of the cystic duct or clean laceration, transection without loss of tissue, extensive defect in the wall, or segmental loss of ductal tissue.

Avulsion of Cystic Duct or Laceration of Common Bile or Hepatic Duct

In the rare patient with avulsion of a portion of the cystic duct, the resultant defect in the side of the common bile duct can be closed using the viable cystic duct remnant or even a portion of the proximal gallbladder wall, if necessary (Fig. 15.3) [30, 31]. Many surgeons choose to insert a T-tube through a separate choledochostomy and pass the proximal limb underneath such an extensive repair.

Fig. 15.3

Sandblom technique to close defect in common bile duct from cholecystocholedochal fistula can be applied to partial avulsion of cystic duct from blunt trauma (From Sandblom et al. [30], Copyright Elsevier 1975)

Primary repair of a lacerated or ruptured duct can be performed in a variety of ways, but interrupted sutures of 5–0 polyglycolic acid are preferred. One option when closure of a longitudinal defect would result in narrowing of the injured duct would be to perform a Heineke-Mikulicz type of transverse repair as described by Rutledge in 1983 [31]. The use of a T-tube with a limb under a simple suture repair of a portion of the wall is controversial because the small size of the ductal system in the previously healthy individual makes insertion of the tube difficult and potentially dangerous [2, 6, 7]. In one patient of Zollinger et al. [11], small ureteral catheters were used as stents across injuries to the hepatic ducts as a #8 Fr T-tube was too large to be inserted. Technical problems associated with the insertion of T-tubes were partially responsible for the discontinuance of routine ductal drainage as an adjunct to the repair of hepatic injuries 20 years ago [32].

Transection Without Loss of Tissue

Transection of the common hepatic or common bile duct by a stab wound with little contusion to the ends is probably one of the few instances in which an end-to-end anastomosis might be considered. Dissection around the ends should be avoided because it disrupts the tenuous blood supply of the duct at 3 and 9 o’clock and increases the risk of a stricture at the site of repair [33]. When tension is present at the anastomosis, a stricture is inevitable. Although long-term follow-up results are lacking in many series, end-to-end anastomoses have been successful in treating traumatic transections in older series [18, 34–37]. A considerable number of reports have appeared, however, of unsuccessful end-to-end anastomoses performed for operative or traumatic transections [4, 6, 7, 38]. In a review of the literature by Ivatury et al. [2], end-to-end anastomoses for traumatic transections in 20 patients resulted in a stricture in 11 (55 %) and the need for biliary enteric bypass.

Extensive Defect in the Wall

An extensive defect in the wall (lateral defect) may result from a missile wound. Although such an injury may be managed by segmental resection of the area of injury and biliary enteric bypass, simpler and faster repairs have been suggested or used successfully in patients with either operative or traumatic injuries. Rutledge [31] originally suggested the use of a full-thickness vascularized jejunal patch in which the mucosa would be facing the lumen of the common bile duct, and this technique was subsequently used with success by another group [39]. In a similar fashion, the serosa of the mobilized duodenum, a loop of jejunum (with enteroenterostomy below), or a Roux-en-Y loop of jejunum has been used successfully to close ductal defects after longitudinal incision of strictured biliary anastomoses [39–41].These approaches would presumably be applicable, as well, to the patient who has sustained trauma with a wall defect.

An innovative approach not widely known has been the use of saphenous vein patches to close ductal defects. Originally described in 1964 [42], Rutledge [31] subsequently described its use in a patient with partial resection of the ductal wall for hepatocellular carcinoma. In 1991, Monk et al. [43] described performing a vein patch cholangioplasty in a patient who had sustained trauma with a 1 by 1 cm noncircumferential defect in the left hepatic duct. Based on the experimental studies of Belzer et al. [44] and Cushieri et al. [45] in which biliary vein patches were noted to shrink, essentially disappear, and be replaced by ingrowth of fibrous tissue, Monk et al. [43] suggested that a stent should be placed beneath the patch as it shrinks.

Segmental Loss of Ductal Tissue

Formal Reconstruction

Segmental loss of ductal tissue results from a missile wound or a severe blunt avulsion injury requiring debridement. Ductal repairs for this group of patients are similar to those used with biliary strictures resulting from operative injuries.

With the loss of the common bile duct below the junction with the cystic duct, a normal gallbladder with a widely patent cystic duct may be used as a biliary conduit to the duodenum or jejunum. Also, it should be noted that the distal duct does not need to be identified and oversewn in such a patient [48]. This is a simple reconstruction involving only oversewing of the stump of the common bile duct at the junction with the cystic duct and an end-to-end or side-to-side cholecystoduodenostomy or cholecystojejunostomy (loop or Roux-en-Y) [31, 49]. Short-term data (<12 months) have long been available on the efficacy of cholecystojejunostomy for biliary drainage in patients with unresectable carcinoma of the head of the pancreas [50].

End-to-side choledochoduodenostomy can be used when a significant portion of the common bile duct has been injured. This option, however, has not been used in any of the large reports of biliary tract injuries in the past, presumably because of concerns about tension on the anastomosis or the potential complication of a side duodenal fistula [1, 2, 6, 7, 51].

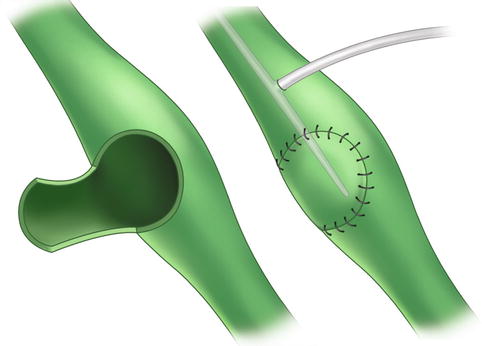

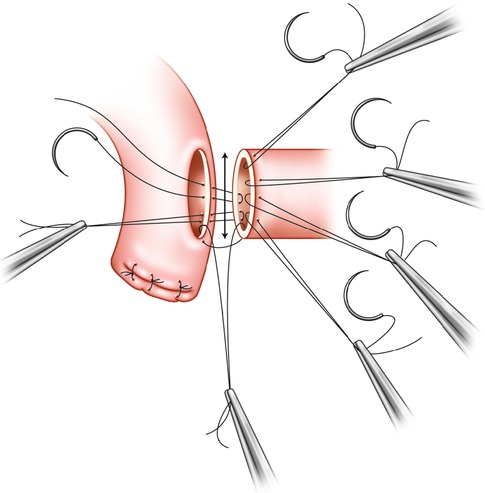

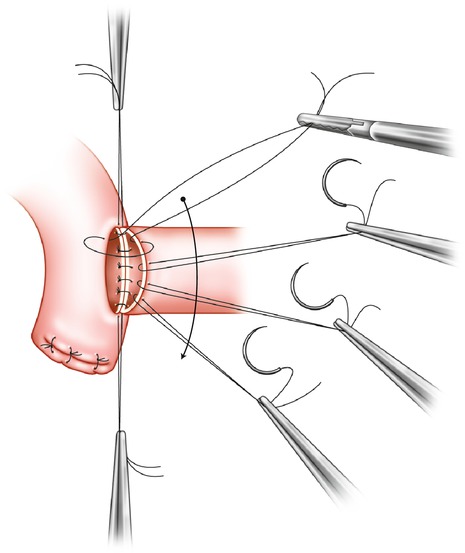

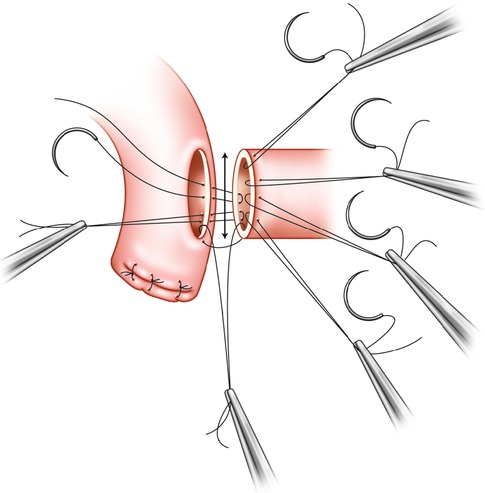

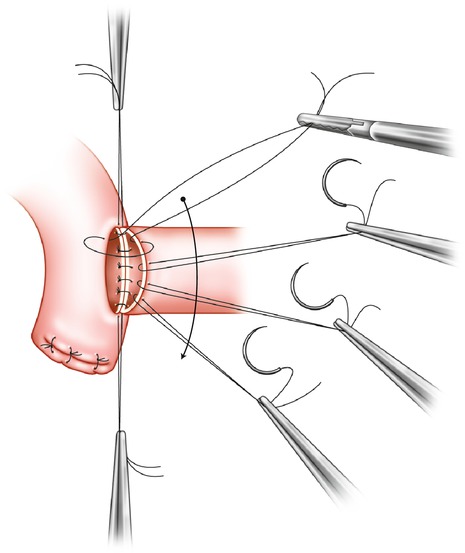

The most popular repair when loss of ductal tissue or a significant avulsion injury has occurred in a patient whose condition is otherwise stable has been Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy or hepatodochojejunostomy (hepaticojejunostomy) [1, 2, 6, 7, 51]. A mobile retrocolic Roux-en-Y limb, a well-vascularized proximal bile duct, and a 1- or 2-layer anastomosis with interrupted sutures usually lead to an excellent result in the patient who has sustained trauma (Figs. 15.4 and 15.5). In the review by Ivatury et al. [2], a stricture developed in only 1 of 28 patients undergoing primary biliary enteric anastomosis for complete transection.

Fig. 15.4

Blumgart technique of Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy after resection of ductal stricture or neoplasm can be applied to patient with significant trauma to the common bile, common hepatic, or hepatic duct. Anterior sutures are passed through biliary duct only, needles are left attached, and sutures are elevated to improve visualization as posterior row of sutures is inserted. Some surgeons place the posterior row of sutures with the knot outside the lumen (From Blumgart [53], Copyright Elsevier 1994)

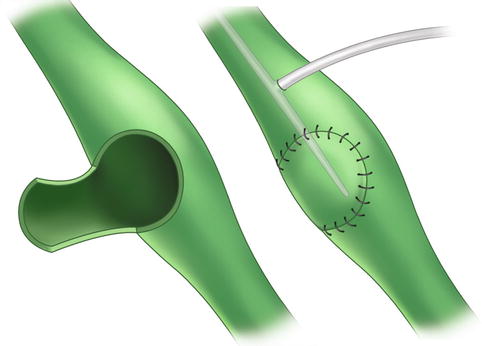

Fig. 15.5

Completion of anterior row of sutures by passing needles full thickness through jejunal in Roux limb (From Blumgart [53], Copyright Elsevier 1994)

With avulsion of the hepatic ducts at the bifurcation, it is worthwhile to suture the right and left ducts together medially before performing an end-to-side hepatodochojejunostomy [52, 53]. It may also be helpful to pass the anterior row of sutures through the common bile channel for traction before placing the sutures through the posterior row as this improves visualization [53].

Complete loss of the hepatic ducts at the surface of the liver is equivalent to the chronic E3 or E4 biliary strictures that Strasberg et al. [54] have described after mishaps during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. When the general surgeon is familiar with the jejunal mucosal graft-on-transhepatic stent technique described by the late Rodney Smith (Lord Smith of Marlow), this is the appropriate approach [55].

A similar injury, but one in which the stumps of the hepatic ducts cannot be identified in the hilum of the liver, is a special challenge. A Roux-en-Y hepatoportal jejunostomy similar to that used in neonates with biliary atresia is performed [56]. This approach has been used with success in Strasberg E4 injuries with stricture after laparoscopic cholecystectomy as well [57].

Role of Stents with Formal Reconstruction

Repair of an acute injury to the extrahepatic ductal system from trauma differs significantly from repair of a chronic biliary stricture. There are no scarring and no residua from previous reconstructions, and most of the patients are young and healthy. If the stump of the resected duct(s) is bleeding freely and the Roux-en-Y choledocho- or hepatodochojejunostomy (hepaticojejunostomy) is performed without tension, there are no data that the presence of a stent will decrease postoperative leaks or strictures.

The small size of the injured ducts as previously described is the one factor that often prompts the insertion of a stent in trauma patients. The presence of a stent in a duct less than 4 mm in size may prevent narrowing during the performance of the bilioenteric anastomosis or during healing and will allow for postoperative imaging [58]. #5 or #8 Fr silastic pediatric feeding tubes, much as used by some surgeons to stent pancreatojejunostomies during Whipple procedures, make ideal biliary stents. They are soft and flexible, decrease pressure on the wall of the duct, and should minimize the incidence of arteriobiliary fistulas [59]. There are no data on the length of time that stents inserted after an acute repair should remain in place.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree