Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms or ‘

LUTS’, is a descriptive term for a symptom complex which is often characterized by bothersome voiding. The investigation of

LUTS is an excellent example of the art of deductive diagnosis as it requires a combination of good history taking, physical examination including digital rectal or pelvic examination, and appropriate use of an array of laboratory, outpatient and complex investigations. The term ‘

LUTS’ itself requires some clarification. Contrary to the term ‘prostatism’ which is inaccurate but has nevertheless remained in common usage, the term

LUTS is more appropriate considering that various forms of urethrovesical dysfunctions often not related to the prostate may contribute to

LUTS, as may other causes outside the urinary tract, obvious examples being excessive diuresis, cardiovascular pathology and diabetes.

When one considers the underlying pathology,

LUTS tend to be rather non-specific. In relation to symptomatic benign prostatic enlargement (

BPE), no specific symptom can reliably suggest benign prostatic hyperplasia, and furthermore there is no correlation between the degree of prostatic enlargement and the severity of symptoms. In addition, the relationship between symptoms and objective data from urodynamic studies is also weak.

In evaluating a person with

LUTS, the clinician should endeavour to formulate a urodynamic diagnosis from the start to achieve an understanding of the individual’s symptoms from an ætiological point of view, on the intuitive presumption that reversal of these causative processes should intuitively lead to more effective management. This is built up progressively from the available clinical information available, and altered accordingly as further information is received. Subsequent confirmation or refutation of this understanding by further investigations also serves to enhance the clinician’s understanding of the disease process.

It should be noted however, that the pathway of achieving a urodynamic diagnosis is not always completed, and often does not need to be, as complex investigations are reserved for more complex situations where the diagnosis is not apparent from initial tests. In clinical practice, the majority of cases actually require a minimum number of tests to achieve a working diagnosis. The diagnostic pathway chosen also depends largely on the presentation and results of preceding tests. For example, the investigation of an elderly man initially presenting with straightforward voiding symptoms suggestive of symptomatic benign prostatic enlargement (

BPE) is quite different from a woman re-presenting after failed incontinence surgery with voiding dysfunction. However, a broad diagnostic pathway is summarized in

Table 3.1.

In general clinical usage, the term

LUTS has become almost synonymous with symptomatic prostatic enlargement without incontinence. Although this chapter encompasses the diagnostic approach of both these conditions in a general sense, the investigation of complicating factors that may underlie

LUTS such as haematuria, urinary tract infections and specialist clinical and urodynamic tests for incontinence are outside its remit.

History and physical examination

The urinary bladder and its outlet function as a continent reservoir which is able to intermittently expel urine under voluntary control in socially acceptable circumstances. Consequently, its functions may be described as occurring in two phases:

LUTS have been classified into storage and voiding symptoms corresponding to the two phases of lower urinary tract function (

Table 3.2). Storage symptoms are usually more bothersome as they are associated with decreased control over an individual’s life, particularly as voiding occurs for relatively small periods of time each day and storage is the predominant normal function by far. The limited expression of bladder dysfunction as either storage or voiding symptoms confers non-specificity to pathological processes.

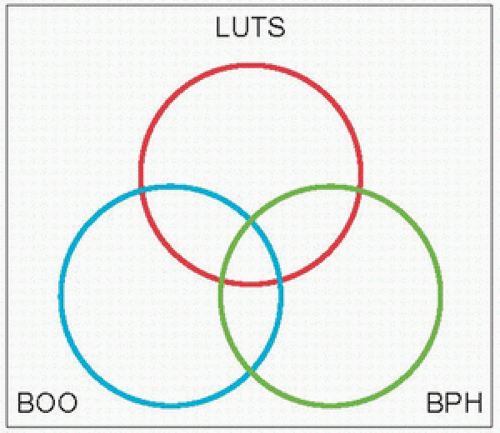

Historically, bladder outlet obstruction (

BOO), ‘prostatism’ and benign prostatic hyperplasia (

BPH) have been considered almost synonymous, with ‘prostatism’ implying a prostatic origin for these symptoms. As alluded to earlier, lower urinary tract symptoms are not specific to the prostate and nor are they gender-specific, as they are also prevalent amongst women; furthermore, the causes of

LUTS may originate from causes outside the urinary tract, as in polyuria which may present as urinary frequency or nocturia. Although

BPH accounts for a large proportion of

LUTS in the older male, other conditions such as bladder dysfunction, neurological disorders, and renal or extra-renal conditions often give rise to

LUTS. This relationship is best illustrated by Tag Hald’s rings (

3.1).

BPH is a histological diagnosis which is the most common urological affliction of older men, affecting 40-70% of men aged 60-70 years. Over 80% of all men with functioning testicles will develop

BPH within their lifetime, and nearly 30% will undergo surgery for this condition. Approximately 15-30% of these men will complain of lower urinary tract symptoms.

LUTS occur in about 25% of men >40 years, with an age-related increase in prevalence.

A detailed history for

LUTS should include:

Details of each symptom including duration, description, severity, association with other symptoms and daily activities, and response to any lifestyle changes.

Related symptoms which require specific investigation such as haematuria, strangury, incontinence and loin pain should be specifically enquired about.

Details of comorbidities and their treatment, and any surgical history.

Specific details of conditions that may give rise to neurogenic bladder dysfunction (e.g. trauma/spinal injury, vertebral degenerative conditions, diabetes, parkinsonism, stroke) and other conditions such as urinary tract infection which may cause similar symptoms.

Current medications including non-proprietary medicines. Medications with anticholinergic properties and diuretics have obvious effects on the bladder. It is useful to find out what has been prescribed for

LUTS in the past and whether they have been helpful.

Average 24-hour fluid intake with details of the type of fluids consumed, particularly caffeinated, carbonated or alcoholic drinks.

Symptom scores

Several symptom scores have been developed as measurement tools to allow the quantification of

LUTS.

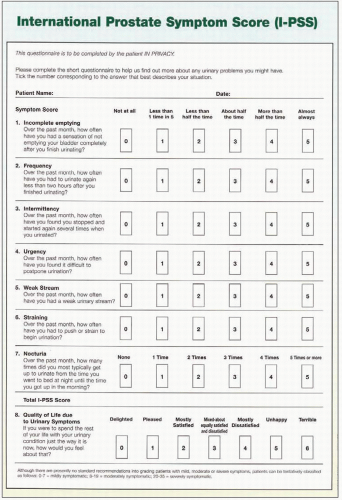

Table 3.3 lists some of the better-known symptom score questionnaires that are in use. The most widely accepted system internationally is the International Prostate Symptom Score (

IPSS).

Most questionnaires are self-completed by patients, but some need to be completed by clinicians, which may therefore be susceptible to bias. The criteria for scientific soundness usually applied to the development of such measures include feasibility, validity, reliability and responsiveness. Feasibility denotes acceptability to users, usually evidenced by high response rates, and includes the cost and technical aspects of implementation of the measuring tool. Validity relates to the extent to which a measurement method measures what it is intended to, and is in turn described by various forms of validity: face, content, criterion, construct, discriminant and convergent. Reliability of a measuring instrument refers to its stability, or the degree to which it will yield the same result on different occasions. Test-retest reliability refers to this stability when the measurement instrument is used in the same situation over a short period of time, usually 2-14 days. Obviously assuming that the domains measured have not actually changed in that period, any change in the readings obtained by the scoring tool is assumed to be an error. Test-retest reliability is best measured by a derivative of the analysis of variance method known as the intraclass correlation coefficient (

ICC) in the case of continuous scales. Internal consistency indicates the extent to which the independent domains or items within a questionnaire all measure the same problem. This is particularly important when a questionnaire contains a large number of items. It also follows that the scores for the individual items should correlate with each other. Internal consistency is most frequently measured by the Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, whereas the Kuder-Richardson formula 20 is more suitable if the responses have a dichotomous response format (e.g. yes/no). Responsiveness of a measurement system refers to the sensitivity of a measure in picking up changes of clinical significance. This property is difficult to measure, but is most frequently estimated by calculating the effect size. The effect size is arrived at by calculating the difference between the mean scores at assessments divided by the standard deviation of the baseline scores, or alternatively the standard deviation of the change scores, and expressed in standardized units which allow comparison.

The

IPSS questionnaire, which has been adopted by the World Health Organization, is derived from and almost identical to the American Urological Association (

AUA)

Symptom Score, with the addition of a quality-of-life domain (

3.2). The

IPSS has excellent test-retest reliability, is internally consistent, and has been translated into several languages for successful use in different populations without loss of efficacy. There are seven domains, each of which can be scored from 0 to 5, giving a maximum score of 35. The

IPSS scoring instrument is recommended for use as a baseline assessment of symptom severity and patients should ideally complete it prior to their appointment with the clinician to allow review during the outpatient consultation in conjunction with history taking. The

IPSS system may be used to categorize an individual’s symptoms as mild, moderate or severe for scores between 0 and 7, 8 and 19, and 20 and 35 respectively.

Symptom scoring systems help the clinician to objectively measure symptoms in individual patients, as well as to obtain a global picture of the degree of bother and the deterioration in quality of life. Examination of the score sheet during the outpatient consultation also helps to direct questions appropriately. Interestingly, high pre-operative symptom scores have been shown to correlate well with good postoperative outcomes. Furthermore, deterioration of symptom scores over a period of time helps identify men at risk of disease progression.

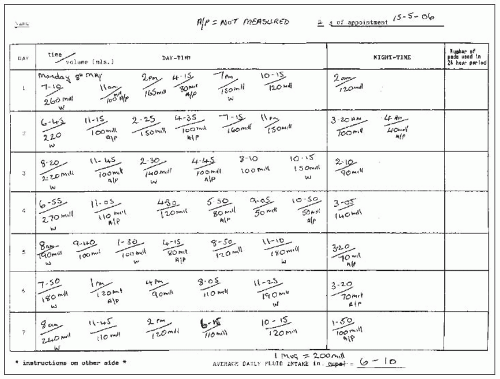

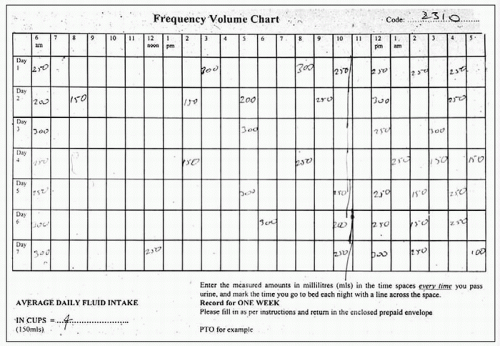

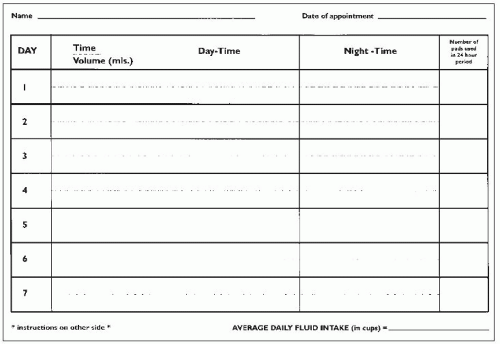

Frequency-volume chart / voiding diaries

Charts which document the volumes and frequency of micturition are an essential part of the evaluation of lower urinary tract symptoms. Often ignored by clinicians as part of the initial evaluation, these actually provide a wealth of useful information. Examinations of charts provide diagnostic clues, help plan urodynamic tests and allow provision of appropriate lifestyle advice. In practice, the patient is sent out a frequency-volume chart with instructions on how to complete it prior to the outpatient appointment. The individual is asked to record the time and volume (in millilitres) of every void for 3-7 days by keeping a measuring jug in the toilet. The chart documents day- and night-time voids separately, along with any episodes of incontinence.

Three types of charts are in usage:

Frequency-volume chart: records the time and volume of each void over a 24-hour period, as described above (

3.3, 3.4).

Bladder diary: considerably more detailed and comprehensive but requires better compliance and attention to detail by patients. In addition to the recording of the voiding times and volumes, it also documents incontinence episodes and severity, 24-hour pad usage, presence and quantification of urgency, and details of fluid intake.

Micturition time chart: represents a simpler version of the preceding two, and comprises a record of the times of voids only.

The recording of the presence and degree of urgency, the use of pads, size and number of pads used over a 24-hour period and degree of pad soakage, provides information on the severity of the problem and its impact on the individual’s quality of life. Charts provide information on frequency, nocturia, average and maximum voided volumes, and help identify relationships between fluid intake and bothersome symptoms. An example is the association between fluid intake in the evenings and severity of nocturia. It is worth remembering that certain types of food such as fruit and vegetables contain significant amounts of water.

Frequency-volume charts may provide important diagnostic clues. They distinguish between nocturia and nocturnal polyuria, and frequency from global polyuria (defined in adults as the production of >2.8 litres of urine in 24 hours). Nocturnal polyuria is identified when the nocturnal voided volume exceeds approximately 30% of the total 24-hour urine output and may reflect the presence of extra-urinary tract pathology such as congestive cardiac failure, and abnormalities of antidiuretic or atrial natriuretic hormone secretion (

3.5). In global polyuria, as may occur in diabetes insipidus or mellitus, or excessive fluid intake, the voided volumes tend to remain normal but occur with increased frequency and a high 24-hour output. In contrast, in the overactive bladder, urgency and increased frequency are generally accompanied by reduced voided volumes.

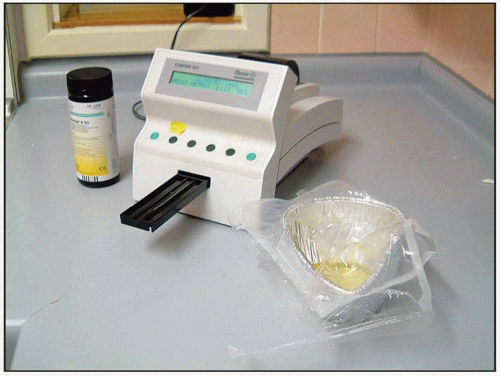

Urinanalysis

Urinanalysis is a fundamental test that must be performed in all patients who present with urinary symptoms. Dipstick analysis of urine is simple to perform and can be done by nurses immediately on presentation at the outpatient clinic or in the ward (

3.6). Dipsticks contain multiple reagent strips that are able to detect the presence of blood, glucose, protein, leukocyte esterase and nitrite in the urine, apart from others

(see Chapter 2).

Formal microscopy of a centrifuged specimen provides confirmation of dipstick findings as well as quantification of haematuria and pyuria. Cultures are indicated when dipstick analysis suggests the presence of infection, or when strong clinical suspicion exists (

3.7).

The primary use of urine dipstick analysis is to rule out significant pathology that may require specific investigations.

Haematuria may indicate the presence of important pathology such as urothelial carcinoma, carcinoma

in situ, urinary tract infections, urethral stricture or urinary stone disease. The diagnostic pathway for the investigation of haematuria is discussed elsewhere, and includes imaging of the urinary tract, cystoscopy, and often urine cytology. Dipstick tests detect the peroxidase-like activity of haemoglobin; orthotolidine is oxidized by cumene

hydroperoxide catalysed by haemoglobin to produce a blue product.

Glycosuria may indicate the presence of diabetes mellitus. Diabetics may develop

LUTS via several mechanisms: peripheral autonomic neuropathy may impair bladder function, osmotic diuresis from the glycosuria may result in polyuria, and glycosuria and impaired bladder emptying may predispose the individual to infection.

Leukocyte esterase and nitrite in the dipstick test detect pyuria and bacteriuria respectively. Although both are important independent indicators of urinary tract infection their sensitivity and specificity is increased when used together. In many cases simple visual examination of turbid offensive urine provides the answer, but this should not replace formal testing.