Evaluation of Adult Kidney Transplant Candidates

Suphamai Bunnapradist

Gabriel M. Danovitch

Kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for most suitable end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients and must be discussed with patients with advancing chronic kidney disease (CKD). The preparation of CKD patients for renal transplantation should start from the time of its recognition and should occur in parallel with efforts to prevent and delay its progression. The improved life expectancy and quality-of-life benefits of transplantation over dialysis therapy have attracted an increasing number of patients to the transplantation option; ideally, patients are evaluated for and undergo transplantation before the initiation of dialysis treatment.

An initial evaluation is followed, if patients are deemed appropriate transplant candidates, by their supervision while awaiting transplantation. Transplant evaluation is aimed not only at assessing the chances of recovery from surgery but also at maximizing short- and long-term survival and assessing the likely impact of transplantation on quality of life. Evaluation of the suitability of kidney transplantation includes medical, surgical, immunologic, and psychosocial issues. The patients’ individual risks and benefits of transplantation are discussed so that they can make an informed decision about whether to proceed with transplantation. After candidates are placed on the deceased donor list, a periodic reevaluation is necessary to address new issues that may affect transplant suitability. In this chapter, guidelines are provided for the evaluation of adult kidney transplant candidates. The evaluation should be tailored according to patient-specific conditions. Center expertise should be taken into account when determining which diagnostic studies should be performed.

The process of referral, evaluation, and preparation of patients for transplantation has been extensively reviewed in the professional literature. Several topics critical to the evaluation process are discussed in detail elsewhere in this book. The immunologic evaluation of transplant recipients is discussed in Chapter 3; recommendations for the screening of candidates for infectious disease are discussed in Chapter 11; evaluation of candidates with viral hepatitis and liver disease is discussed in Chapter 12; evaluation of diabetic candidates and the various options for pancreatic transplantation are discussed in Chapter 15; evaluation of children is discussed in Chapter 16; psychiatric evaluation is discussed in Chapter 17; and psychosocial and financial issues and assessment of compliance are discussed in Chapter 20. Guidelines for the referral and management of patients eligible for solid-organ transplantation have been proposed by the Clinical Practice Committee of the American Society of Transplantation (see Steinman and colleagues in “Selected Readings”). For a detailed algorithmic approach to the evaluation of renal transplant candidates, refer to the clinical practice guidelines developed by the American Society of Transplantation (see Kasiske and associates in “Selected Readings”). For a detailed discussion of the deceased donor transplant waiting list, see Gaston and associates in “Selected Readings.” The proceedings of the Lisbon Conference on the Care of

the Kidney Transplant Recipient is a valuable resource of recommendations and references (see Abbud-Filho and colleagues in “Selected Readings”). The Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipients (SRTR) provides annual updates on the status of the kidney transplant waiting list in the United States. The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) initiative under the leadership of Kasiske and Zeier is developing guidelines on the care of the renal transplant recipient which will become available in late 2009.

the Kidney Transplant Recipient is a valuable resource of recommendations and references (see Abbud-Filho and colleagues in “Selected Readings”). The Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipients (SRTR) provides annual updates on the status of the kidney transplant waiting list in the United States. The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) initiative under the leadership of Kasiske and Zeier is developing guidelines on the care of the renal transplant recipient which will become available in late 2009.

PART I. EVALUATION OF TRANSPLANT CANDIDATES BENEFITS OF EARLY REFERRAL

In ideal circumstances, preparation for transplantation begins as soon as progressive CKD is recognized. Chronic renal disease care, care on dialysis, and transplant care are interdependent. Increased cardiovascular risk, which is a major determinant of post-transplantation morbidity and mortality, can be recognized as soon as the serum creatinine level is elevated. The various aspects of the care of patients with CKD are beyond the scope of this text. Better managed patients with CKD, both before and after commencement of chronic dialysis, make better transplant candidates. Patients without the major contraindications to transplantation listed in Table 7.1 should be referred to a transplantation program when they approach stage 4 CKD or a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 30 mL per minute. Patients should understand that referral to a kidney transplantation program does not imply immediate transplantation.

Early referral of patients to nephrologic care during the course of CKD permits better preparation for dialysis and transplantation. Patients who are referred to the care of a nephrologist at least 1 year before commencement of renal replacement therapy are documented to have decreased morbidity and mortality. Unfortunately, 25% to 50% of CKD patients are unaware of their problem until ESRD develops. Transplantation before the commencement of dialysis, called preemptive transplantation, has been convincingly shown to improve post-transplantation graft and patient survival. Five- and 10-year graft survival rates are 20% to 30% better in patients who received either no dialysis or less than 6 months of dialysis than for those who received more than 2 years of dialysis. The benefit of preemptive transplantation is likely largely a result of the avoidance of the cardiovascular consequences of long-term dialysis (see Chapter 1).

In the United States, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) deceased donor kidney allocation algorithm in place in 2009 (see

Chapter 4), patients may begin to accrue points on the deceased donor transplant waiting list when the GFR is estimated to be 20 mL per minute or less. However, less than 5% of patients added to the waiting list are predialysis. Because of the long wait anticipated for a deceased donor transplant, preemptive transplantation is infrequent in these patients, unless they are fortunate to be allocated a “zero-mismatch” kidney (see Chapter 4). The great advantage of early referral is that it permits recognition and evaluation of potential living donors and the elective timing of the transplantation so as to avoid dialysis and the necessity for placement of dialysis access. Avoidance of access placement is a great and tempting benefit, but it is one that must be considered carefully. If there is a reasonable doubt that a living donor is available, or that the workup of the donor can be completed expeditiously, it may be wiser to place a permanent access to avoid reliance on temporary access techniques that bring with them added morbidity.

Chapter 4), patients may begin to accrue points on the deceased donor transplant waiting list when the GFR is estimated to be 20 mL per minute or less. However, less than 5% of patients added to the waiting list are predialysis. Because of the long wait anticipated for a deceased donor transplant, preemptive transplantation is infrequent in these patients, unless they are fortunate to be allocated a “zero-mismatch” kidney (see Chapter 4). The great advantage of early referral is that it permits recognition and evaluation of potential living donors and the elective timing of the transplantation so as to avoid dialysis and the necessity for placement of dialysis access. Avoidance of access placement is a great and tempting benefit, but it is one that must be considered carefully. If there is a reasonable doubt that a living donor is available, or that the workup of the donor can be completed expeditiously, it may be wiser to place a permanent access to avoid reliance on temporary access techniques that bring with them added morbidity.

TABLE 7.1 Major Contraindications to Kidney Transplantation | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Because of the varied course of advanced CKD, it is hard to provide a precise point when referral for transplantation should be made. Patients with diabetic nephropathy typically progress rapidly through the advanced stages of CKD, whereas patients with interstitial nephritis, for example, may progress slowly. Patients with a GFR in the 20s, and patients whose course suggests they will become dialysis dependent in 1 to 2 years, should be referred.

Delays to Referral

All dialysis centers in the United States are mandated to be associated with transplantation centers, and all Medicare patients are legally entitled to referral for transplant evaluation. Unfortunately, there are wide variations in access to transplantation because of delays in the referral process that may tend to disadvantage ethnic minorities and other vulnerable population groups. The large size of the United States and its varied population density also introduce formidable geographic barriers to equality of access. It is the responsibility of nephrologists, dialysis unit staff, transplantation program staff, and the patients themselves to do their utmost to minimize delays and barriers to transplantation.

EVALUATION PROCESS

Patient Education and Consent

Patient education is at the core of the process. Transplant evaluation implies not only the medical assessment of the potential recipient by the transplantation team but also the assessment by the patients of transplant option and its relevance to their well-being. The evaluation process is an opportunity to counsel patients about their ESRD options and to advocate for their welfare. It should not be an obstacle course for patients to pass or fail!

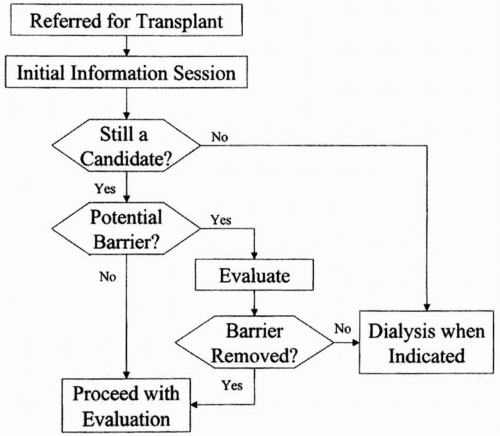

Figure 7.1 illustrates the structure of the evaluation process. All potential transplant candidates should be encouraged to attend an information session, preferably accompanied by family members and friends. At the informational meeting, the risks of the operation and the side effects and risks of immunosuppression should be explained to the patient and family members. The surgical procedure and its complications should also be discussed. The relative benefits of living donor and deceased donor transplantations should be compared and contrasted in the context of the prolonged wait that is anticipated for a deceased donor transplant in the event that a living donor is not available. Graft survival and morbidity statistics from the transplantation program and from national data should be shared with the patient and family members. The nature of rejection should be explained and discussed along with the increased risk for infection, malignancy, and mortality. Patients should be informed about donor risk factors, particularly those associated with deceased

donation (see Chapter 4). Patients should be warned that even a successful transplantation may not last forever and that at some point they may be required to return to dialysis. The importance of compliance with dialysis and dietary prescription while waiting for transplantation and with immunosuppressive therapy after transplantation should be emphasized. The possibility of post-transplantation pregnancy should be discussed with women of childbearing age (see Chapter 10).

donation (see Chapter 4). Patients should be warned that even a successful transplantation may not last forever and that at some point they may be required to return to dialysis. The importance of compliance with dialysis and dietary prescription while waiting for transplantation and with immunosuppressive therapy after transplantation should be emphasized. The possibility of post-transplantation pregnancy should be discussed with women of childbearing age (see Chapter 10).

In the United States, the Center for Medicare Services requires that a formal consent process be made available to all patients seeking kidney transplantation. The transplantation program, however, must ensure that the process is not merely a legalistic one and that patient consent truly represents an educated understanding of the options available.

Candidates for Extended Criteria Donor Kidneys

As of 2009, deceased donor kidneys in the United States are categorized as being standard criteria donor kidneys (SCD) and extended criteria donor kidneys (ECD). The precise definition of ECD kidneys, the rationale for their use, and anticipated changes in the categorization of deceased donor kidneys using a donor-risk index are described in Chapter 4. The regulations for the allocation of ECD kidneys mandate that transplant candidates be informed about the benefits (shortening of waiting time) and risk (impaired long-term graft function) associated with their use. They should sign an informed consent document. A useful guiding principle when counseling patients is to compare the additional risk of accepting an ECD kidney (or a kidney with a high donor risk index) with the risk of remaining on dialysis for a prolonged period while waiting for an SCD kidney (or a kidney with a low donor risk index). Candidates for ECD kidneys are usually 60 years of age or older (younger if they are diabetic or have coronary heart disease); have failing dialysis access; or are particularly intolerant of dialysis. Patients in their 60s who have been on the waitlist

for several years may do better to wait for an SCD kidney because they should not have to wait long. Patients going on the list in their 60s may not survive long enough to enjoy an ideal kidney and would be well advised to accept an ECD kidney if they are offered one. The waiting time for SCD and ECD kidneys varies geographically, and patients should be informed of the anticipated waiting time in their geographic area to facilitate an educated decision.

for several years may do better to wait for an SCD kidney because they should not have to wait long. Patients going on the list in their 60s may not survive long enough to enjoy an ideal kidney and would be well advised to accept an ECD kidney if they are offered one. The waiting time for SCD and ECD kidneys varies geographically, and patients should be informed of the anticipated waiting time in their geographic area to facilitate an educated decision.

Educational Resources

Potential transplant candidates and their family members should be encouraged to attend formal educational sessions and to obtain further information through available literature, including center-specific outcomes. They should also be familiar with the main features of deceased donor organ allocation policy (Chapter 4). Patient-orientated educational material is available in the United States in printed and electronic form from the American Society of Transplantation (http://www. a-s-t.org), the National Kidney Foundation (http://www.kidney.org), and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) (http://www.unos.org). The UNOS website also provides detailed information on the performance of individual transplant programs, so-called center-specific data, which can assist patients who have the opportunity to elect the program to which they wish to be referred.

Who Is Not a Transplant Candidate?

The risks and benefits of transplantation should be explained during the initial session because some patients may decide that they do not want to proceed with the evaluation, thus avoiding the need for a costly and time-consuming evaluation. Table 7.1 lists the major contraindications to transplantation. Although some contraindications to transplantation are absolute, many are relative and are determined by local policy and experience. For example, some programs exclude patients who are morbidly obese, or who continue to smoke despite being requested to stop. Attitudes vary about transplantation in the aged or the extent of cardiovascular disease deemed acceptable for transplant candidates. Of the nearly 300,000 patients on dialysis in the United States as of early 2009, only about 25% are on the kidney transplant waiting list (see Chapter 1). Most of the unlisted patients are aged and have multiple medical morbidities, but many patients are potential candidates who have yet to be referred for transplantation or who have encountered delays in the process. Patients should be presumed to be transplant candidates until shown otherwise. If there is any question regarding a transplant contraindication, the patient should be referred to the transplantation program to make that determination. Patients should be entitled to a second opinion if they find the recommendation of the transplantation program to be unreasonable or unacceptable to them.

Conventional and Innovative Transplantation

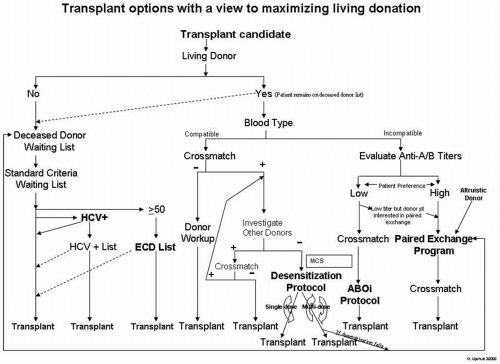

Ideally, transplant candidates are unsensitized (see Chapter 3) and have motivated, healthy, ABO-compatible, crossmatch-negative, living donors available to donate to them. If no living donors are available, patients have no option but to wait for a deceased donor transplant, although some patients may elect to shorten their wait by agreeing to accept a lower-quality organ. Patients with hepatitis C may elect to accept a kidney from a deceased donor with hepatitis C (see Chapter 12). In the event that a potential living donor is available but is incompatible by virtue of ABO or histocompatibility differences, another living donor should be evaluated. If a living donor is available but apparently incompatible innovative protocols may be available. ABO-incompatible transplantation and desensitization protocols for histoincompatible donors may be available. Various forms of paired exchange programs designed to facilitate

ABO and histocompatible living donation are described in Chapter 6. Figure 7.2 provides an algorithm that can guide patient and program choice and is designed to maximize the opportunities for living donation. Not all of the innovative options described in this algorithm are available at all transplantation programs, although hopefully they will become so for patients who are “difficult to transplant.”

ABO and histocompatible living donation are described in Chapter 6. Figure 7.2 provides an algorithm that can guide patient and program choice and is designed to maximize the opportunities for living donation. Not all of the innovative options described in this algorithm are available at all transplantation programs, although hopefully they will become so for patients who are “difficult to transplant.”

ROUTINE EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

A detailed medical history at the time of initial evaluation should be obtained, and efforts should be made to determine the cause of underlying renal disease. Estimation of urine output is important because it may help to determine the significance of the urine output in the early postoperative period and helps to determine the necessity for further urologic evaluation. If a kidney biopsy has been performed, the report should be sought and reviewed. Family history is extremely important because it may provide information regarding the cause of the renal failure and may also allow the physician to initiate discussion regarding living related donation. The evaluation of patients with potentially recurring renal diseases after transplantation is discussed later in the chapter and in Chapter 16.

A detailed cardiovascular history is mandatory for all recipients, and patients should be instructed about symptoms of cardiac disease while awaiting transplantation. Risk factors for coronary artery disease should be sought in the history, including a history of diabetes, smoking, family history of coronary artery disease, and previous cardiac events. Exercise tolerance should be assessed. A history of claudication warrants an evaluation for peripheral vascular disease and may also point toward a higher chance of ischemic heart disease. A full

physical examination must be performed, including evaluation for evidence of congestive heart failure, carotid artery disease, and peripheral vascular disease. The presence of femoral bruits and poor peripheral pulses may warrant further evaluation of the pelvic vasculature with either a Doppler ultrasound or a magnetic resonance angiogram (see Chapter 13). The presence of strong femoral and peripheral pulses is a valuable indicator to the transplant surgeon that the pelvic vessels will be adequate for the transplant vascular anastomosis (see Chapter 8).

physical examination must be performed, including evaluation for evidence of congestive heart failure, carotid artery disease, and peripheral vascular disease. The presence of femoral bruits and poor peripheral pulses may warrant further evaluation of the pelvic vasculature with either a Doppler ultrasound or a magnetic resonance angiogram (see Chapter 13). The presence of strong femoral and peripheral pulses is a valuable indicator to the transplant surgeon that the pelvic vessels will be adequate for the transplant vascular anastomosis (see Chapter 8).

A detailed history of infectious disease should be obtained (see Chapter 11). This should include assessment for possible exposure to tuberculosis, such as history of residence or travel to endemic areas, prior exposure, any prior treatment, and the duration of treatment. Evidence of other possible infections, including hepatitis and endemic fungal infections, should be sought. Male patients older than 40 years should undergo a rectal examination with a digital prostate examination and a prostate-specific antigen estimation. All women should have a Papanicolaou test and a pelvic examination. Women older than 40 years should undergo a mammogram to evaluate for malignancy. All patients older than 50 years and those younger than 50 years with guaiac-positive stools should undergo colonoscopy.

Laboratory Studies

A complete blood count and a chemistry panel should be obtained along with a prothrombin time and partial prothrombin time. Blood should be sent for blood and tissue typing. Patients should be screened for evidence of hepatitis B and C, syphilis, HIV, and cytomegalovirus. A screening purified protein derivative and a screening chest radiograph may be required for certain population to assess for evidence of prior tuberculosis exposure or infection. Patients with a positive skin test or abnormal chest radiograph and those who are allergic to tuberculin and who have risk factors for tuberculosis infection may require preventive therapy with isoniazid (see Chapter 11). A urinalysis and urine culture should be performed on all urinating patients. In the event of proteinuria, a 24-hour urine collection for protein should be obtained, which may reflect the cause of primary kidney disease and be a guide for further management.

EVALUATION OF SPECIFIC TRANSPLANTATION RISK FACTORS RELATED TO ORGAN SYSTEM DISEASE

Cardiovascular Disease

The cardiovascular evaluation of diabetic transplant candidates is discussed in Chapter 15, and evaluation of patients on the transplant waiting list is discussed in Part II of this chapter. Most transplantation teams include a designated cardiologist to assist in the evaluation of the often complex issues of assessing and managing cardiovascular disease in the CKD population.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death after renal transplantation. Almost half of deaths in patients with functioning grafts occurring within 30 days after transplantation are due to cardiovascular disease, primarily acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovascular disease is the major cause of longterm mortality and death with graft function, and cardiovascular disease is the major cause of late graft loss (see Chapter 10). All patients with CKD are at high cardiac risk, although for some, the risk is particularly high. Diabetic patients, older patients, patients on dialysis for prolonged periods, and patients with multiple Framingham Study risk factors for coronary artery disease are generally recommended to undergo noninvasive cardiac testing; routine testing of lower-risk asymptomatic patients may not be necessary. Because many dialysis patients are unable to exercise adequately, noninvasive testing usually takes

the form of chemical stress echocardiography or scintography. Patients with a positive stress test should proceed to a coronary angiogram. A prior history of ischemic heart disease has been found to be a major risk factor for post-transplantation ischemic events, so that all patients with a history of myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure should undergo cardiac stress testing or, possibly, angiography, even if the stress test is negative. Risk factors associated with post-transplantation ischemic heart disease include age more than 50 years, diabetes, and an abnormal electrocardiogram. Most transplantation programs use noninvasive testing as their initial mode of screening for coronary artery disease, although some prefer to go directly to coronary angiogram. Data are unavailable to test the effectiveness of more expensive screening techniques such as using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET), or electron-beam computed tomography (CT). Both dobutamine stress echocardiogram and dipyridamole sestamibi have similar sensitivities in detecting coronary artery disease in the non-ESRD population. Specific sensitivities and sensitivities for the ESRD population are lacking. Patients who have critical lesions should probably undergo correction with either coronary artery bypass surgery, angioplasty, or stent placement before transplantation.

the form of chemical stress echocardiography or scintography. Patients with a positive stress test should proceed to a coronary angiogram. A prior history of ischemic heart disease has been found to be a major risk factor for post-transplantation ischemic events, so that all patients with a history of myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure should undergo cardiac stress testing or, possibly, angiography, even if the stress test is negative. Risk factors associated with post-transplantation ischemic heart disease include age more than 50 years, diabetes, and an abnormal electrocardiogram. Most transplantation programs use noninvasive testing as their initial mode of screening for coronary artery disease, although some prefer to go directly to coronary angiogram. Data are unavailable to test the effectiveness of more expensive screening techniques such as using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET), or electron-beam computed tomography (CT). Both dobutamine stress echocardiogram and dipyridamole sestamibi have similar sensitivities in detecting coronary artery disease in the non-ESRD population. Specific sensitivities and sensitivities for the ESRD population are lacking. Patients who have critical lesions should probably undergo correction with either coronary artery bypass surgery, angioplasty, or stent placement before transplantation.

Calcific aortic stenosis and valvular heart disease are common in transplant candidates, and when they are suspected, it is important to perform an echocardiogram to elicit systolic or diastolic dysfunction because this may have important prognostic implications. Reversible myocardial dysfunction should be treated. Irreversible heart failure should probably preclude renal transplantation unless heart transplantation is also considered. However, many patients with mild to moderate cardiac dysfunction may respond to renal transplantation with an improvement in myocardial function. In many cases, an improvement in the ejection fraction has been documented after transplantation.

Recent or metastatic malignancy*

Recent or metastatic malignancy* Untreated current infection

Untreated current infection Severe irreversible extrarenal disease

Severe irreversible extrarenal disease Recalcitrant treatment nonadherence

Recalcitrant treatment nonadherence Psychiatric illness impairing consent and adherence

Psychiatric illness impairing consent and adherence Current recreational drug abuse

Current recreational drug abuse Aggressive recurrent native kidney disease

Aggressive recurrent native kidney disease Limited, irreversible rehabilitative potential

Limited, irreversible rehabilitative potential Primary oxalosis

Primary oxalosis