Introduction and Classification of Complications of Ileal Pouch

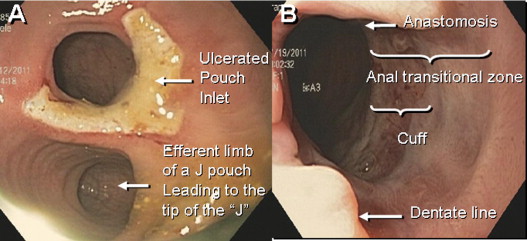

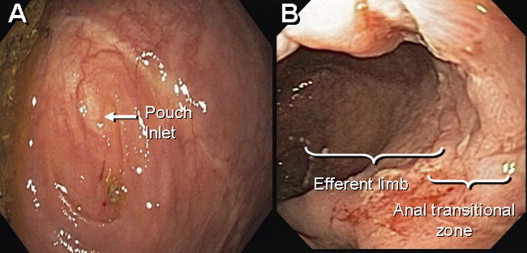

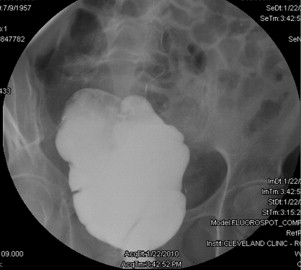

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) eventually require surgery for failure of medical therapy or development of neoplasia. Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA), initially described in 1978, has become the surgical treatment of choice for the majority of patients with UC who require proctocolectomy. Pouch configuration with two (J), three (S), or four (W) loops of small intestine has been performed, and the J pouch has become the most commonly used one. The normal configurations of the J and S pouch are illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2 . The IPAA procedure preserves intestinal continuity, substantially decreases the risk for dysplasia, and improves health-related quality of life. However, adverse sequelae related to the ileal pouch occur frequently. Recognition and proper diagnosis of those conditions are key for maintaining a healthy pouch and prolonging pouch survival.

Early complications are common after restorative proctocolectomy. The most frequent are bowel obstruction, pouch bleeding, pelvic and wound sepsis. Late complications include stricture of the anastomosis, fistula and abscess, reduced fertility, and pouchitis. Of these complications, pouchitis is the most frequent. The majority of nonmechanical pouch-related complications can be addressed without surgical intervention. However, pouch failure does occur. Pouch failure is defined as the need for permanent diversion, with or without pouch excision or revision. The reported cumulative incidence of pouch failure ranged from 4% to 10%. A metaanalysis of 43 studies of 9317 patients showed that pouch failure rate after IPAA increases proportionally to the length of follow-up: from 6.8% with a median follow-up period of 37 months to 8.5% after more than 60 months. The most common causes for pouch failure are pelvic sepsis, chronic refractory pouchitis, Crohn disease (CD) of the pouch, and pouch fistula or sinus.

Based on published studies as well as the authors’ clinical experience in the unique subspecialty Pouchitis Clinic at the Cleveland Clinic, the authors proposed a classification system of pouch-related complications in 2008 ( Box 1 ). The complications are classified into mechanical, inflammatory, functional, neoplastic, and metabolic conditions related to the pouch by suspected underlying pathophysiologic condition. In this article, the authors provide an update for evaluation of ileal pouch disorders.

Surgical and mechanical

∘ Anastomotic leaks

∘ Pelvic/perianal sepsis and abscess

∘ Pouch sinuses

∘ Pouch fistulae

∘ Strictures

∘ Afferent limb and efferent limb syndromes

∘ Infertility and sexual dysfunction

∘ Portal vein system thrombi

∘ Pouch prolapse, twisted pouch, pouch bleeding, sphincter injury or dysfunction, pouchocele

Inflammatory and infectious

∘ Pouchitis

∘ Cuffitis

∘ Crohn disease of the pouch

∘ Proximal small bowel bacterial overgrowth

∘ Inflammatory polyps

Functional

∘ Irritable pouch syndrome

∘ Anismus

∘ Pseudoobstruction or megapouch

∘ “Pouchalgia fugax”

Dysplastic and neoplastic

∘ Dysplasia or adenocarcinoma of the pouch or anal transitional zone

∘ Squamous cell cancer at the anal transitional zone

∘ Lymphoma

Systemic and metabolic

∘ Anemia from chronic disease or iron or vitamin B 12 deficiency

∘ Bone loss

∘ Vitamin D deficiency

∘ Nephrolithiasis

∘ Celiac disease

Surgical and Mechanical Complications

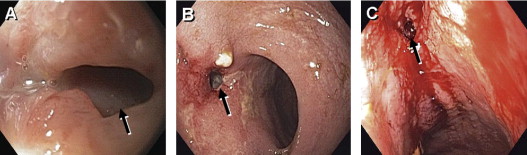

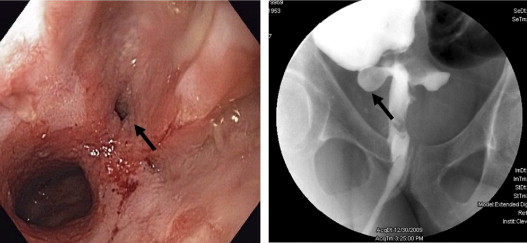

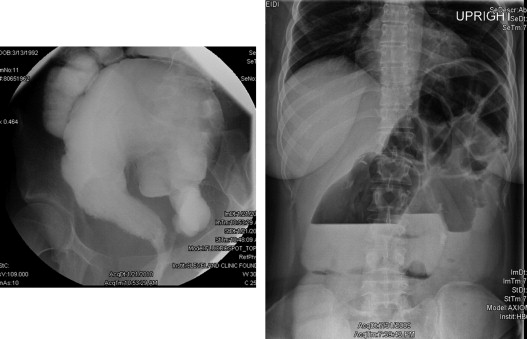

Surgical or mechanical complications are those adverse sequelae that are caused mainly by factors related to the surgery; these include anastomotic leaks, pelvic sepsis and abscess, pouch sinuses and fistulae, strictures, afferent limb syndrome and efferent limb syndrome, infertility, portal vein thrombi, pouch prolapse, and pouch twist. Anastomotic leak is defined as anastomotic separation leading to exodus of pouch luminal content. The most common location of an anastomotic leak is at the pouch-anal anastomosis followed by the tip of the “J”, and the body of the pouch along the staple line ( Fig. 3 ). Pelvic sepsis is defined as any infective process present in the peripouch area or at the true pelvis distal to the pelvic inlet, whereas pelvic abscess is a collection of purulent exudates without demonstrable anastomotic leaks. Pouch sinus, which is typically a later presentation of an initial anastomotic leak, is defined as a blind tract that may lead to abscess cavity ( Fig. 4 ). Pouch fistula ( Fig. 5 ) is defined as an abnormal passage from one epithelial surface (ie, the ileal pouch) to another epithelial surface (eg, vagina, bladder, or skin). Afferent limb syndrome is defined as distal small bowel obstruction caused by an acute angulation, prolapse, or intussusceptions of the afferent limb at the junction to the pouch ( Fig. 6 ). Efferent limb syndrome typically occurs in patients with an S pouch with a dysfunctional or excessively long efferent limb, which partially obstructs the outlet of the pouch ( Fig. 7 ). Other surgery-related complications include pouchocele and pouch mucosal or full-thickness prolapse ( Fig. 8 ), anal sphincter injury or dysfunction, adhesions, small bowel obstruction, pouch and small bowel herniation or intussusceptions, twisted pouch, and incisional hernia.

Inflammatory Disorders

Pouchitis is the most common long-term complication in patients with IPAA. The reported cumulative frequency rate of pouchitis 10 to 11 years after IPAA surgery for UC ranges from 23% to 46%. Furthermore, it is commonly recognized that the incidence of pouchitis increases proportionally to the length of follow-up; approximately 50% of patients after IPAA for UC will develop at least one episode of pouchitis. The cause and pathogenesis of pouchitis are unknown. It is speculated that pouchitis is an abnormal mucosal immune response to altered commensal bacterial flora in the reservoir causing acute or chronic inflammation. Reported risk factors for pouchitis ( Box 2 ) include genetic polymorphisms of interleukin-1-receptor antagonist and NOD2/CARD15 ; noncarrier status of tumor-necrosis factor allele 2 ; extensive UC ; the presence of backwash ileitis ; precolectomy thrombocytosis ; preoperative corticosteroid use ; extraintestinal manifestations, especially the presence of concurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) or arthralgia or arthropathy ; seropositive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) or anti-CBir1 flagellin ; being a nonsmoker ; S pouch reconstruction ; the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) ; and the presence of concurrent autoimmune disorders.

Genetic

• Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist

• NOD2/CARD15

• Noncarrier status of tumor-necrosis factor allele 2

Preoperative disease distribution

• Extensive ulcerative colitis

• Presence of backwash ileitis

• Disease proximal to splenic flexure

Demographic

• Age at operation

• Age at diagnosis

• Nonsmoker

Surgical

• S-pouch reconstruction

• Two-stage instead of three-stage operation

Laboratory

• Precolectomy thrombocytosis

• Seropositive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA)

• Seropositive anti-CBir1 flagellin

Extraintestinal manifestations

• Presence of concurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis

• Presence of concurrent arthralgia or arthropathy

• Presence of concurrent autoimmune disorders

Medication

• Preoperative corticosteroid use

• Use of NSAIDs after pouch construction

In patients with a stapled pouch–anal anastomosis, in order to allow transanal insertion of the stapler head, it is normally necessary to leave a 1- to 2-cm strip of the rectal columnar cuff, which is at risk for developing symptomatic inflammation (cuffitis) or dysplasia. Cuffitis typically represents a recurrence of UC in the residual mucosa. However, other disease processes may also contribute to the development of cuffitis, such as CD and ischemia. In a study of 61 consecutive symptomatic patients with IPAA, 7% had cuffitis. Bleeding ranging from blood on tissue paper to frank blood or blood clots was significantly more common in cuffitis than in pouchitis. Cuffitis may represent an underrecognized disease with limited data in literature. No standardized diagnostic criteria have been proposed.

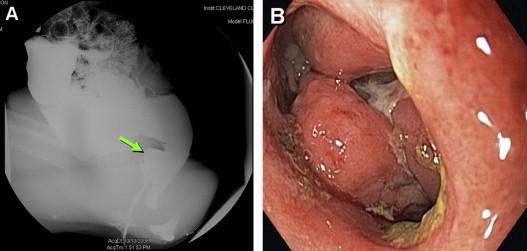

An intriguing inflammatory disorder is CD-like condition of the pouch. CD of the pouch can occur after IPAA, which is intentionally performed in a selected group of patients with Crohn colitis without small intestinal or perianal diseases. CD is also unexpectedly found in proctocolectomy specimens in patients with a preoperative diagnosis of UC or colonic inflammatory bowel disease unclassified (IBDU). However, a majority of patients with CD of the pouch were considered to develop the disease de novo. The reported cumulative frequencies of CD of the pouch range from 2.7% to 13%. Clinically, CD of the pouch can be classified into inflammatory, fibrostenotic, or fistulizing phenotypes. Diagnosis of CD of the pouch often needs a combined assessment of symptom, endoscopy, histology, radiography, and sometimes examination under anesthesia.

Other inflammatory disorders related to the pouch include proximal small bowel bacterial overgrowth and inflammatory polyps. Polyps in the pouch and anal transitional zone (ATZ) mucosa are more common in patients with IPAA for familial adenomatous polyposis than patients with UC. Inflammatory polyps in underlying UC patients are typically detected on the background of pouchitis, cuffitis, or CD. Endoscopic polypectomy with concomitant medical therapy is recommended for large, non-CAP (>10 mm in size) and/or symptomatic (the ones causing obstruction or bleeding) polyps for the eradication of dysplasia or symptom relief.

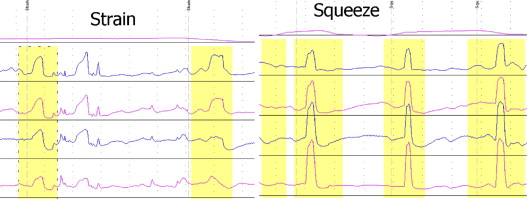

Functional Disorders of the Ileal Pouch

Irritable pouch syndrome (IPS) is a functional disorder in patients with IPAA. It is a diagnosis of exclusion based on the presence of increased frequency of bowel movements with a change in stool consistency, abdominal pain, and perianal or pelvic discomfort in the absence of endoscopic, radiographic, or histologic abnormalities. Patients with anismus, with characteristic paradoxical contractions on pouch-anal manometry, present with dyschezia ( Fig. 9 ). Anismus can be classified as primary (in the absence of mechanical or inflammatory conditions of the distal pouch or ATZ) and secondary (due to mechanical or inflammatory conditions, such as distal pouch stricture, cuffitis, and perianal fistula). Some patients, particularly men, may present with periodic sharp and lightning-type pain at the distal pouch, a condition termed pouchalgia fugax . Pseudoobstruction with megapouch can also occur after IPAA ( Fig. 10 ).

Neoplasia

Proctocolectomy with IPAA substantially reduces, but does not completely abolish, the risk for UC-associated dysplasia or cancer. As of 2011, a total of 77 patients with pouch dysplasia and 50 with pouch cancer have been reported. In a large cohort study from the authors’ group, they reported that the cumulative incidence for pouch cancer at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years was 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.8%, 2.4%, and 3.4%, respectively. Pooled prevalence of dysplasia in the pouch body seems higher than that in the ATZ; however, pouch adenocarcinoma has been discovered more often in ATZ (64%) than in the pouch body (19%). Patients with a longer duration of UC (irrespective of duration of IPAA), a preoperative or intraoperative diagnosis of dysplasia or cancer from underlying UC, the presence of pancolitis with backwash ileitis, villous atrophy of the pouch mucosa or histologic type C mucosa (pouch mucosa with persistent severe atrophy), chronic pouchitis, or PSC are at higher risk for dysplasia or cancer in the pouch or ATZ. In our historical cohort study, the main risk for pouch neoplasia is the presence of UC-associated dysplasia or cancer in colon before colecomy. Routine surveillance pouchoscopy annually is recommended for patients at risk.

Metabolic and Systemic Complications

Systemic complications such as iron deficiency anemia and bone loss are frequently observed post-IPAA. The prevalence of anemia has been reported to be 17% among ileal pouch patients with underlying UC and 26% in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Low bone mineral density was found in 26% in the spine and 19% in the femoral neck of IPAA patients. The pathophysiologic cause for anemia and bone loss may be multifactorial. All the following factors can contribute to anemia: poor oral iron intake, inadequate iron absorption, chronic inflammation, overt or obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, vitamin B 12 malabsorption, and malignancy. Bone loss is associated with low body mass index, advanced age, inflammation activity, nonuse of daily calcium supplement, and villous atrophy of the pouch mucosa. The authors also anecdotally notice that nephrolithiasis are common in patients with IPAA Vitamin D deficiency was also found to be common in pouch patients.

Clinical Evaluation

Symptoms and Signs

Patients with diseased pouches can have a variety of clinical presentations. However, symptoms are nonspecific and commonly not sufficiently distinctive for a definitive diagnosis. Increased stool frequency, urgency, hematochezia, abdominal pain, and perianal pain are the most common symptoms. Dyschezia or incomplete evacuation can be seen in anismus, afferent/efferent limb syndrome, and dysfunctional megapouch. Nausea, vomiting, and bloating could signify small bowel obstruction, pouch strictures, or afferent/efferent limb syndromes. Patients with fistula, drainage, and perianal pain should be evaluated for CD of the pouch, postoperative leaks, sinus, or abscess. Gas, incontinence, nocturnal symptoms, and liquid stools are rarely noted in the normal pouch in patients with an intact anal sphincter. Of note, constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and weight loss are uncommon in patients with conventional pouchitis.

Although symptoms are not typically diagnostic for specific complications of IPAA, bleeding is almost exclusively seen in cuffitis. Patients with presacral sinus or abscess may present with characteristic pain at the distal tail bone. Patients with pouch-vaginal fistula typically present with continuous or intermittent vaginal discharge of air and/or stool or recurrent vaginitis. Patients with pouch-vesicular fistula may present with frequent refractory urinary tract infection. The diagnosis of pouch problems may not be static. For example, a patient may have typical pouchitis at one point and may present with characteristics of CD of the pouch later. Hence, periodic diagnostic endoscopy combined with symptom assessment and histologic evaluation are important in differentiating the causes of pouch problems.

Extraintestinal manifestations such as erythema nodosum and arthralgia can occur in patients with healthy or diseased pouches. In fact, patients with extraintestinal manifestations may have a higher risk for developing pouchitis. Patients with concurrent PSC may present with liver-associated signs or symptoms such as icterus and jaundice. Patients with PSC are at higher risk for chronic pouchitis as well as enteritis. We postulate that PSC-associated pouchitis/enteritis may represent a unique form for disease entity of IPAA.

Detailed physical examination may yield clues for diagnosis and differential diagnosis of ileal pouch disorders. Special attention should be paid to the previous ileostomy site, surgical incision area in the abdomen (for trigger point pain, hernia, or wound infection), and perianal area (for abscess, fistula, skin tags, prolapse, hemorrhoids, dermatitis).

Clinical Evaluation

Symptoms and Signs

Patients with diseased pouches can have a variety of clinical presentations. However, symptoms are nonspecific and commonly not sufficiently distinctive for a definitive diagnosis. Increased stool frequency, urgency, hematochezia, abdominal pain, and perianal pain are the most common symptoms. Dyschezia or incomplete evacuation can be seen in anismus, afferent/efferent limb syndrome, and dysfunctional megapouch. Nausea, vomiting, and bloating could signify small bowel obstruction, pouch strictures, or afferent/efferent limb syndromes. Patients with fistula, drainage, and perianal pain should be evaluated for CD of the pouch, postoperative leaks, sinus, or abscess. Gas, incontinence, nocturnal symptoms, and liquid stools are rarely noted in the normal pouch in patients with an intact anal sphincter. Of note, constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and weight loss are uncommon in patients with conventional pouchitis.

Although symptoms are not typically diagnostic for specific complications of IPAA, bleeding is almost exclusively seen in cuffitis. Patients with presacral sinus or abscess may present with characteristic pain at the distal tail bone. Patients with pouch-vaginal fistula typically present with continuous or intermittent vaginal discharge of air and/or stool or recurrent vaginitis. Patients with pouch-vesicular fistula may present with frequent refractory urinary tract infection. The diagnosis of pouch problems may not be static. For example, a patient may have typical pouchitis at one point and may present with characteristics of CD of the pouch later. Hence, periodic diagnostic endoscopy combined with symptom assessment and histologic evaluation are important in differentiating the causes of pouch problems.

Extraintestinal manifestations such as erythema nodosum and arthralgia can occur in patients with healthy or diseased pouches. In fact, patients with extraintestinal manifestations may have a higher risk for developing pouchitis. Patients with concurrent PSC may present with liver-associated signs or symptoms such as icterus and jaundice. Patients with PSC are at higher risk for chronic pouchitis as well as enteritis. We postulate that PSC-associated pouchitis/enteritis may represent a unique form for disease entity of IPAA.

Detailed physical examination may yield clues for diagnosis and differential diagnosis of ileal pouch disorders. Special attention should be paid to the previous ileostomy site, surgical incision area in the abdomen (for trigger point pain, hernia, or wound infection), and perianal area (for abscess, fistula, skin tags, prolapse, hemorrhoids, dermatitis).

Endoscopic Evaluation

Diagnosis

Endoscopic evaluation is valuable for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of inflammatory and mechanical pouch disorders. A gastroscope is preferred because of its flexibility and smaller caliber. The common endoscopic features shared by pouchitis, CD of the pouch, and cuffitis at different segments of IPAA include erythema, nodularity, increased granularity, loss of vascular pattern, hemorrhage, mucous exudates, friability, ulcers, and erosions, which are all listed in the Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI) instrument ( Table 1 ). Endoscopy helps to assess the prepouch ileum, pouch body, and rectal cuff or ATZ for signs of CD of the pouch and cuffitis. Cuffitis occurs specifically in patients with a stapled IPAA with a retained rectal cuff. The presence of isolated, afferent limb ulcers should raise the suspicion of CD of the pouch, NSAID-related pouchitis, or ischemia. Pouch ischemia may specifically present with asymmetric distribution of pouch inflammation, particularly with half of the pouch inflamed and the other half noninflamed, which usually has a sharp demarcation between the two parts along the suture line. Occasionally pseudomembrane may be observed in patients with Clostridium difficile pouchitis. Therefore, the absence of pseudomembranes under endoscopy does not exclude C difficile infection (CDI) in suspected patients with an ileal pouch. Endoscopy is also useful for the diagnosis of IPS, because IPS is currently a diagnosis of exclusion.

| Criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| Clinical | |

| Stool frequency | |

| Usual postoperative stool frequency | 0 |

| 1–2 stools/d >postoperative usual | 1 |

| 3 or more stools/d >postoperative usual | 2 |

| Rectal bleeding | |

| None or rare | 0 |

| Present daily | 1 |

| Fecal urgency or abdominal cramps | |

| None | 0 |

| Occasional | 1 |

| Usual | 2 |

| Fever (temperature >37.8°C) | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Present | 1 |

| Endoscopic inflammation | |

| Edema | 1 |

| Granularity | 1 |

| Friability | 1 |

| Loss of vascular pattern | 1 |

| Mucous exudate | 1 |

| Ulceration | 1 |

| Acute histologic inflammation | |

| Polymorphic nuclear leukocyte infiltration | |

| Mild | 1 |

| Moderate + crypt abscess | 2 |

| Severe + crypt abscess | 3 |

| Ulceration per low-power field (mean) | |

| <25% | 1 |

| 25%–50% | 2 |

| >50% | 3 |

Dysplasia Surveillance

Pouch endoscopy is the main tool to detect pouch neoplasia. Endoscopy with surveillance biopsy is recommended annually in high-risk pouch patients, such as patients after 10 years of UC diagnosis, with a preoperative diagnosis of UC-associated neoplasia, in addition to those who have chronic inflammatory conditions of the pouch, family history of colorectal cancer, or concomitant PSC. Although there is no consensus on where and how endoscopic biopsy should be performed, four to six pieces need be taken from the ATZ for surveillance. Dysplasia or cancer lesions are often harbored in the underlying inflammation of the pouch or ATZ; this condition can present as flat mucosa, ulcerated lesions, or masslike lesions. Large (>1-cm) polypoid lesions of the pouch or ATZ should be removed endoscopically because of potential possibility to be neoplastic (8.7%, 2 of 23). Pouch dysplasia or cancer may have no endoscopically visible lesions. Therefore, blind biopsy of normal or abnormal ATZ mucosa is advocated in high-risk patients. New techniques, such as high-magnification chromoscopic pouchoscopy, have been reported to permit more accurate anatomical localization of the residual rectal mucosa and ATZ in vivo and permit improved biopsy accuracy. Imaging enhanced endoscopy, such as narrow band imaging and confocal microscopy, may also be considered for detecting dysplasia in pouch patients.

Therapeutic Pouch Endoscopy

Pouch endoscopy can treat certain structural diseases of the pouch, such as endoscopic balloon dilatation of pouch inlet or outlet strictures, even the angulated and tight strictures. Recently, Doppler ultrasound–guided endoscopic needle knife stricturoplasty for refractory anastomotic stricture has been first introduced by the authors. In addition to treatment for strictures, successful endoscopic needle knife treatment of presacral sinus at the anastomosis was also reported by the authors’ group. Based on the (B.S.) own experience, healing of the anastomotic sinus may succeed in half of selected patients. With the development of novel therapeutic instruments, the authors believe that more surgery-related complications could be treated endoscopically.

Laboratory Evaluation

Laboratory tests are usually performed for the following purposes: (1) investigation of risk factors associated with cause, pathogenesis, and prognosis of pouch disorders; (2) assessment of disease activity, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis between inflammatory and noninflammatory pouch disorders; (3) microbiological evaluation to identify superimposed infection from pathogens; and (4) evaluation of metabolic and systemic adverse sequelae associated with IPAA.

Laboratory Tests in Assessing Risk Factors and Implication in Pathogenesis

Immunogenotypic markers have been studied extensively in pouchitis. Dysregulated cytokine production including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and abnormalities in endogenous inhibitors of these cytokines such as IL-1 receptor antagonist and soluble TNF-α receptors, have been reported in pouchitis. Polymorphisms of TNF-α have been also investigated as a risk factor for pouchitis. Carriage of the TNF-α allele2 was found to be inversely associated with pouchitis. Polymorphisms of NOD2 (nucleotide binding oligomerization domain-2)/CARD15 (caspase recruitment domain family member-15), which are associated with ileal CD, have a higher prevalence in patients with pouchitis. However, these genetic tests are not routinely performed in patients suspected of having ileal pouch disorders.

The IBD-associated serology markers, such as perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA), have been investigated in patients with pouchitis or CD of the pouch. In prospective studies, both pANCA and anti-CBir1 expression were found to be associated with pouchitis. Anti- Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) are antibodies directed against a cell wall component of the yeast, S cerevisiae . Preoperative presence of ASCA immunoglobulin (Ig) A antibodies in patients with UC may have a higher risk of developing CD of the pouch after IPAA surgery. Patients with positive ASCA may also be at an increased risk for the development of fistulas postoperatively. Some of these antimicrobial antibodies were reported to be associated with chronic pouchitis and CD-like complications of the pouch.

Laboratory Tests for Assessment of Disease Activity and Diagnosis of Ileal Pouch Problems

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), a nonspecific marker of inflammation, has been studied as a marker of pouchitis. In reported studies, ESR was found to correlate with the PDAI score and episodes of pouchitis. C-reactive protein (CRP) has also been evaluated as a marker of pouchitis disease activity. A significant correlation was observed between CRP and the PDAI score. Elevated CRP levels might be useful to monitor the degree of inflammatory activity in a pouch noninvasively. However, the CRP level as a snapshot had a limited role in distinction between a healthy and diseased pouch based on longitudinal clinical and endoscopic evaluation. In a separate study from the authors’ center, false-positive celiac serology was discovered to be common in patients with IPAA, and it might be associated with chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis. Therefore, in the authors’ clinical practice, they routinely screen for celiac disease, along with other autoimmune markers (such as antimicrosomal antibodies in the subgroup of patients with chronic pouchitis, because it may coexist and contribute to worsening symptoms in IPAA patients.

Fecal inflammatory markers may closely reflect the presence of intestinal inflammation. Fecal pyruvate kinase, calprotectin, and lactoferrin are being investigated to assess the correlation with pouchitis and PDAI scores. Recently, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for fecal calprotectin concentration (>300 μg/g) to detect recurrent pouchitis were reported to be 57%, 92%, 67%, and 89%, respectively. Fecal lactoferrin assay as an initial evaluation may be more cost effective for the diagnosis of pouchitis than routine pouchoscopy with biopsy. These simple laboratory tests may be cost-effective for evaluating pouchitis and may be used as an adjunct first-line modality to pouch endoscopy.

Microbiological Evaluation

Microbiota play a key role in the initiation and exacerbation of pouch inflammation. Attempts have been made to identify the culprit pathogens for inflammatory conditions of the pouch. Stool bacterial culture and sensitivity tests are not a part of routine clinical practice but may have some value in identifying sensitive bacteria in the treatment antibiotic-refractory pouchitis. A recent study reported fecal coliform sensitivity analysis to successfully identify effective antibiotic therapy for patients with antibiotic-resistant pouchitis.

CDI can occur in patients who have undergone a colectomy; it has been recently recognized in patients with an IPAA, particularly in those with chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis. Although patients with C difficile can be healthy carriers, fulminant or even lethal CDI can occur in pouch patients. CDI should be excluded in pouch patients with active symptoms with or without endoscopic findings of pouchitis or other pouch disorders. There has been a wide range of reported sensitivities in enzyme immunoassay-based C difficile toxin assays. At present, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing seems to be the only single, rapid test method available with a high sensitivity and specificity for directly detecting virulent C difficile . Practicing clinicians should have a high index of suspicion of CDI in managing patients with pouch disorders.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in patients with IPAA was also recognized as a cause that may superimpose inflammation of the pouch reservoir, even if most reported patients were immunocompetent. Patients who presented as chronic pouchitis refractory to antibiotics and those who have systemic symptoms, such as general malaise and fever, should be suspected of and tested for CMV infection. In the authors’ clinical practice, pouch endoscopy with the biopsy for immunohistochemistry as well as CMV DNA by PCR in the blood is often useful for detecting CMV infection.

Laboratory Tests for Evaluations of Systemic Adverse Sequelae Associated With IPAA

The IPAA procedure with or without inflammatory complications can be associated with various systemic and metabolic conditions, such as anemia, vitamin B 12 deficiency, and bone loss. Early identification and diagnosis of these conditions would help in administering appropriate further evaluation and therapeutic intervention. Hemoglobin and hematocrit are critical for patients with IPAA, because anemia is present in 17% of IPAA patients with underlying UC. Bone metabolism can be assessed by measuring serum levels of parathyroid hormone, osteocalcin, 25-hydroxyvitamin D 3 , calcium, alkaline phosphatase, and urinary N -telopeptide cross-linked of type I collagen in patients with IPAA. In the authors’ previous study, abnormal liver function tests (LFTs) were observed in 17.4% of pouch patients. The presence of coexisting autoimmune disorders, family history of IBD, extensive colitis before colectomy, the presence of PSC, and a high body mass index were found to be risk factors for any abnormal LFTs. Patients with the previously mentioned risk factors need to have LFTs as a part of their routine evaluation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree