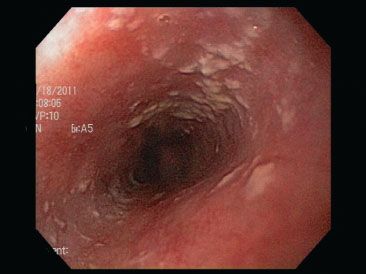

Figure 1.1 Unremarkable endoscopic appearance of the esophagus. The pink-tinged mucosal surface appears relatively smooth and homogenous throughout the esophagus. There are no visible plaques, nodules, masses, ulcers, erythema, blood, varices, stenoses, or diverticula. Variations of luminal caliber in the image may stem from esophageal peristalsis, anatomic bends, and constriction points.

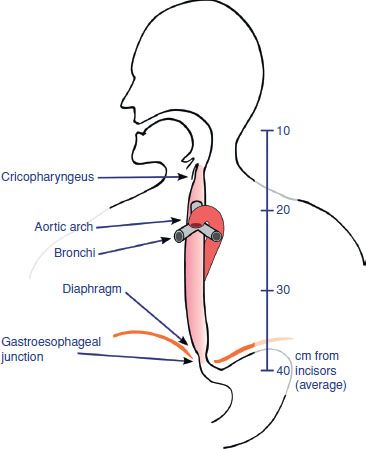

Figure 1.2 Anatomic esophageal constriction points include the esophageal inlet, crossing of the aortic arch, left main bronchus, and diaphragmatic hiatus. These sites are prone to narrowing and can lead to pill impaction and associated local tissue damage.

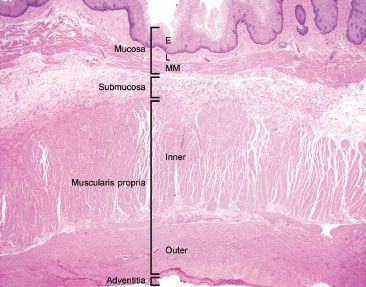

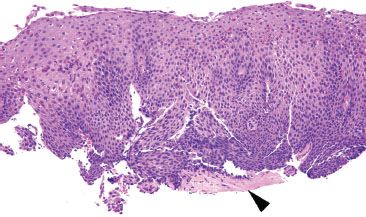

Figure 1.3 This resection specimen illustrates the four main layers of the esophagus: Mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and adventitia. The mucosa consists of epithelium (E), lamina propria (L), and muscularis mucosae (MM). The submucosa sits between the muscularis mucosae and the muscularis propria (MP) and it consists of loose fibroconnective tissue and lymphovascular channels. The MP consists of inner circular and outer longitudinally oriented muscle fibers. Finally, the outermost layer is the adventitia. The esophagus lacks a serosa.

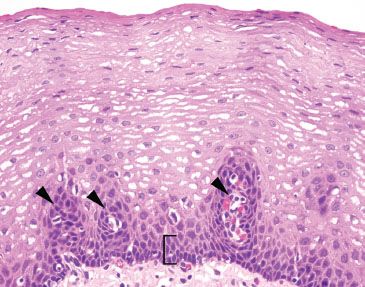

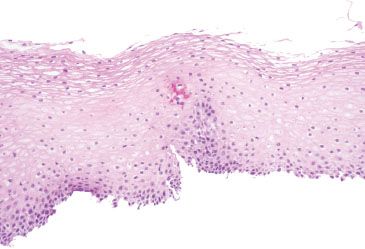

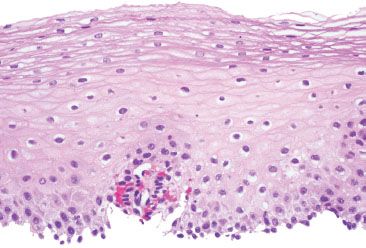

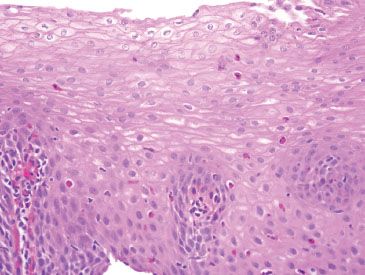

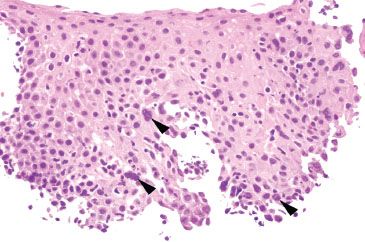

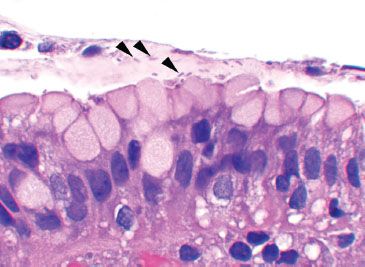

Figure 1.4 Unremarkable esophageal squamous mucosa. Note the basal layer is only a few cell layers thick (bracket) and the vascular papillae are confined to the lower one-third of the epithelial thickness (arrowheads).

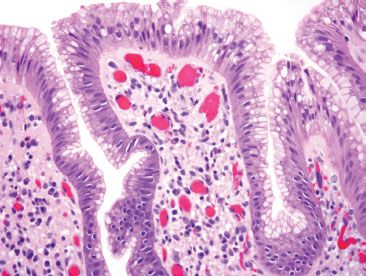

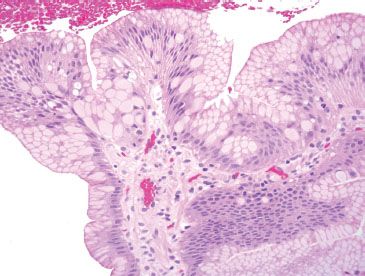

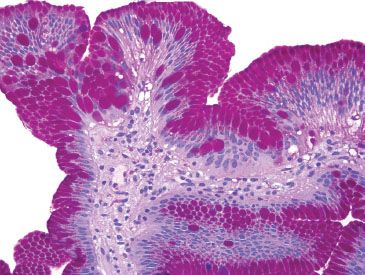

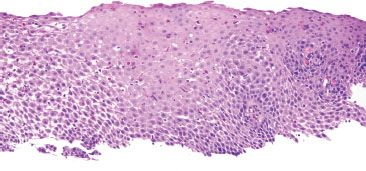

Figure 1.5 Unremarkable cardiac mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction. The columnar cells are of foveolar type, with apical intracytoplasmic neutral mucin that would be magenta on a PAS/AB.

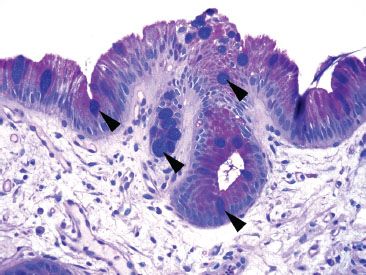

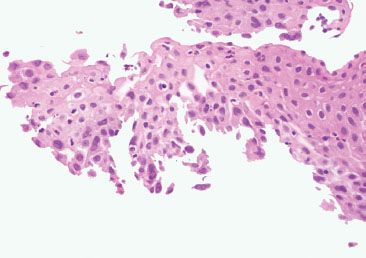

Figure 1.6 Pseudogoblet cells. Pseudogoblet cells are important mimics of true goblet cells of Barrett esophagus and are typically found in clusters. They can be mistaken for true goblet cells due to their abundant cytoplasmic mucin.

PEARLS & PITFALLS

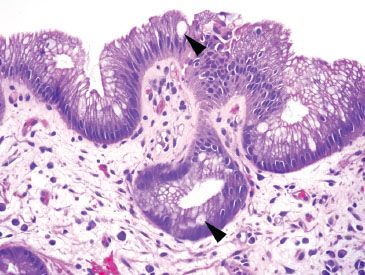

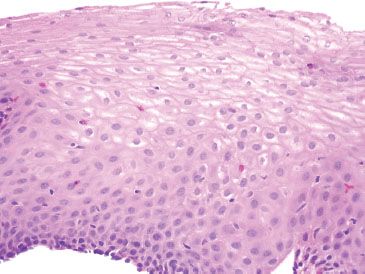

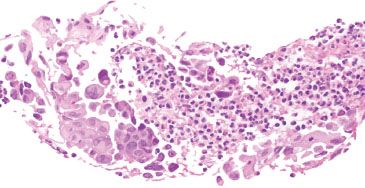

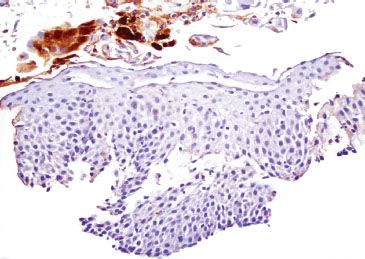

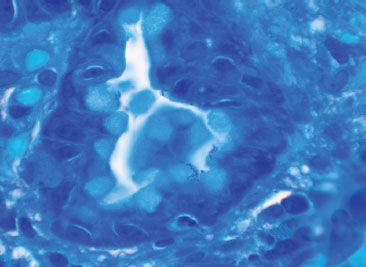

Beware of pseudogoblet cells, which are important mimics of true goblet cells. Pseudogoblet cells are foveolar epithelial cells with prominent cytoplasmic distention and key distinctions from true goblet cells include the following: (1) Pseudogoblets tend to aggregate in clusters, whereas true goblet cells are more sparsely distributed among absorptive cells (complete metaplasia) or foveolar cells (incomplete metaplasia). (2) Pseudogoblet cells have predominantly neutral mucin (magenta, PAS/AB) in contrast to the acid mucin of a true goblet cell (deeply basophilic, PAS/AB) (Figs. 1.6–1.10).

Figure 1.7 Pseudogoblet cells (PAS/AB). On PAS/AB stain, the neutral mucin in the pseudogoblet cells is magenta. True goblet cells contain acidic mucin, and are deeply basophilic on PAS/AB.

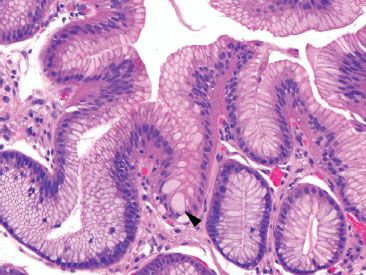

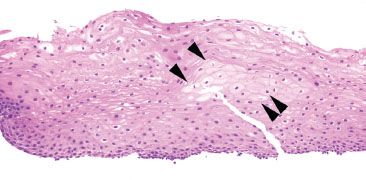

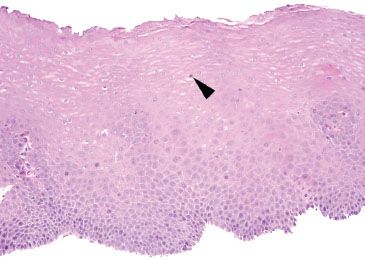

Figure 1.8 Pseudogoblet cells (arrowhead).

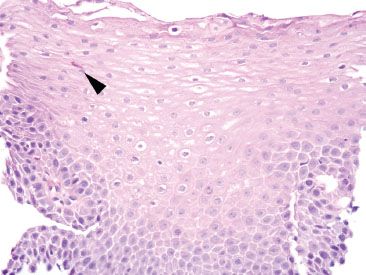

Figure 1.9 True goblet cells. In contrast to pseudogoblet cells, true goblet cells are sparsely distributed (arrowheads).

Figure 1.10 True goblet cells (PAS/AB). In contrast to pseudogoblet cells, true goblet cells (arrowheads) have a deeply basophilic appearance on a PAS/AB.

FAQ: What is the utility of and recipe for Periodic acid Schiff/alcian blue, pH 2.5 special stain (PAS/AB)?

Answer: The combination PAS/AB allows for simultaneous evaluation of a number of important diagnostic features, such as fungal forms (magenta), goblet cells (deeply basophilic), an intact small bowel brush border (crisp and uniform stain condensation). The stain also highlights the mucin of sneaky adenocarcinomas.

1% ALCIAN BLUE, pH 2.5 RECIPE*

Alcian blue 8GX……..5 g

Acetic acid, 3% solution….500 mL

Adjust the pH to 2.5. Filter and add a few crystals of thymol.

*This solution is commercially available.

PAS/AB pH 2.5 RECIPE

1. Deparaffinize and hydrate to distilled water.

2. One minute in 3% acetic acid. Do not rinse.

3. Stain in Alcian Blue pH 2.5 for 30 minutes.

4. Rinse in tap, then distilled water.

5. Oxidize in 0.5% periodic acid solution for 10 minutes.

6. Rinse in distilled water.

7. Place slides in Schiff reagent for 20 minutes.

8. Wash in running tap water for 5 minutes, or until water is clear and sections are pink.

9. Stain in Harris hematoxylin for 3 minutes.

10. Wash in tap water.

11. Clarifier for 1 minute.

12. Wash in tap water for 1 minute.

13. Bluing reagent for 1 minute.

14. Wash in running water for 1 minute.

15. Dehydrate through 95% alcohol, absolute and clear in xylene.

16. Mount.

Recipe courtesy of Deborah Duckworth, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Histology Laboratory.

FAQ: Are there histologic clues that confirm the biopsy site as esophagus (and not cardia, for example)?

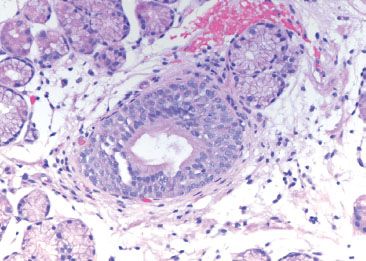

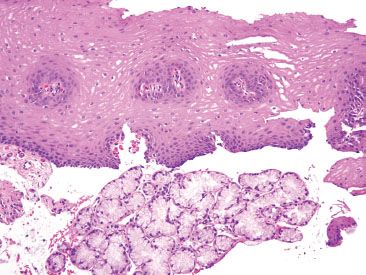

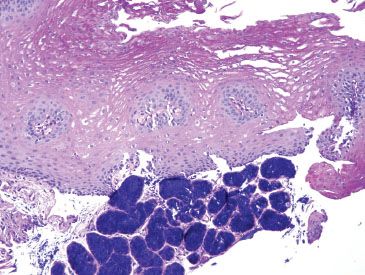

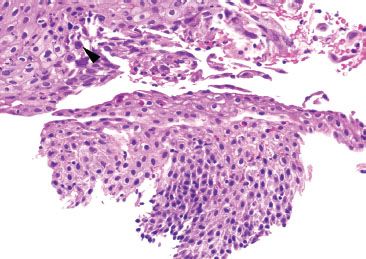

Answer: Yes. Establishing the tissue origin as esophagus is critical for the diagnosis of Barrett mucosa, a diagnosis that necessitates periodic surveillance based on an increased risk of neoplasia. Usually correlation with the endoscopic report provides the most effective means to determining the tissue site of origin. Unfortunately, detailed reports are not always provided, and clinicians may not be confident that they are in the tubular esophagus, especially if a patient has a sliding hiatal hernia. Since esophageal ducts transmit secretions from the esophageal submucosal glands to the luminal surface, their histologic identification can establish the tissue site as esophagus, providing helpful diagnostic clues (Figs. 1.11–1.20).

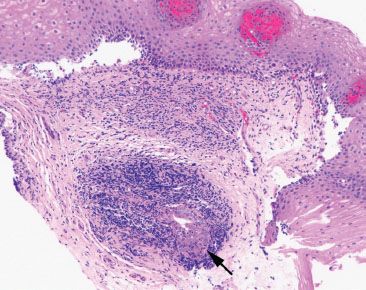

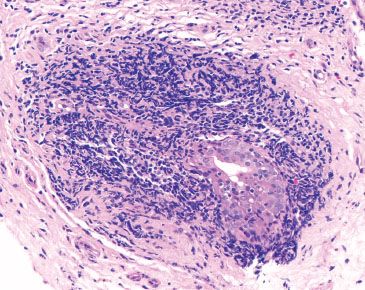

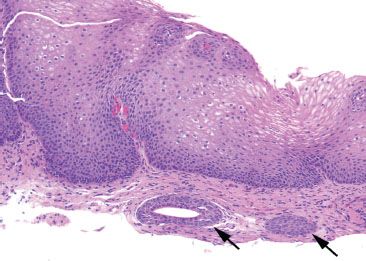

Figure 1.11 Esophageal ducts. Esophageal ducts confirm the site of origin as esophageal (arrow). If goblet cells were present on this tissue fragment, they would signify Barrett esophagus, assuming an abnormal endoscopic examination.

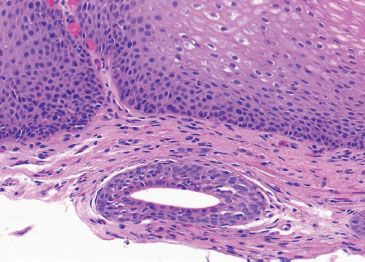

Figure 1.12 Esophageal duct. Higher power of previous figure. Periductal chronic inflammation is a typical finding. Squamoid metaplasia of the ducts is not uncommon.

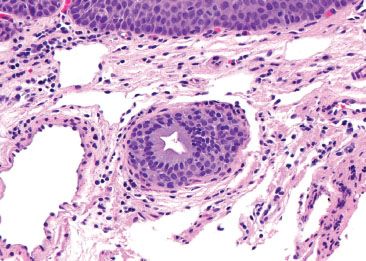

Figure 1.13 Esophageal ducts. This esophageal duct is present in the lamina propria, amidst a background of lymphovascular spaces. The overlying squamous epithelium can be seen (top).

Figure 1.14 Esophageal ducts (arrows).

Figure 1.15 Esophageal duct. Higher power of previous figure.

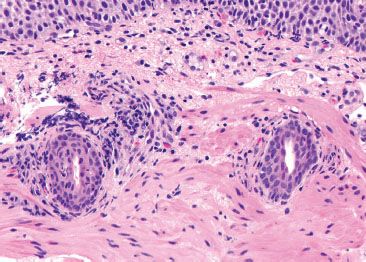

Figure 1.16 Esophageal ducts. These ducts are traversing the muscularis mucosae en route from submucosal glands. Their presence indicates that the tissue origin is esophageal.

Figure 1.17 Esophageal duct (arrowhead). This biopsy predominantly consists of oxyntic-type glandular mucosa. An esophageal duct (arrowhead) signifies that this biopsy was taken from the tubular esophagus. The proximity to gastric oxyntic glands emphasizes the variability of gastric cardia length among patients; while some patients may demonstrate several centimeters of gastric cardiac-type mucosa, others transition directly from esophagus to oxyntic mucosa, like this patient.

Figure 1.18 Esophageal duct. Higher power of previous figure.

Figure 1.19 Esophageal glands. Esophageal glands produce mucoprotective products that help lubricate the passage of food and, at the same time, protect the integrity of the esophageal mucosa.

Figure 1.20 Esophageal glands (PAS/AB). The esophageal glands stain deeply basophilic on PAS/AB. In contrast, cardiac-type mucosal glands would appear magenta on PAS/AB (Fig. 1.7).

ACUTE ESOPHAGITIS PATTERN

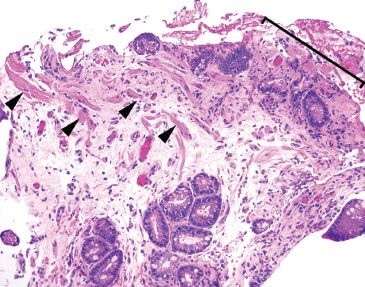

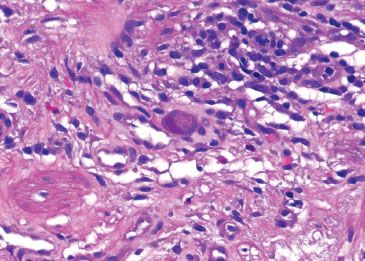

Figure 1.21 CMV esophagitis. This example of acute esophagitis shows prominent ulceration, mixed inflammation, and reactive endothelial and stromal cells. A CMV immunostain confirmed a diagnosis of CMV esophagitis.

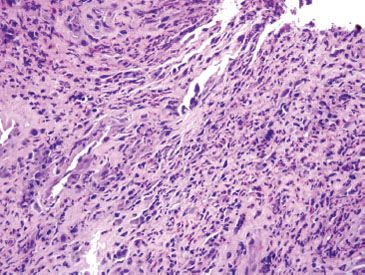

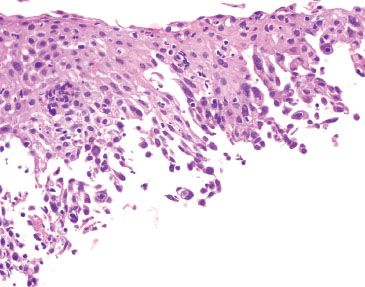

Acute esophagitis describes an injury pattern that includes intraepithelial neutrophils, erosions, and/or ulcerations (Fig. 1.21). This pattern of injury is entirely nonspecific, but is most commonly caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), infections, and medications. Malignancy, amyloidosis, radiation injury, and vasculitis are also potential causes of acute esophagitis, particularly if erosions and ulcerations are present. While findings in ulcer debris are easy to overlook since ulcers have a “busy” visual appearance, the cause of the ulcer can occasionally be identified by careful inspection.

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the Acute Esophagitis Pattern

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Infections

Infections

Medications

Medications

Other

Other

Figure 1.22 Erosion. The surface epithelium is eroded and accompanied by fibroinflammatory debris (bracket). By definition, an erosion is confined to the mucosa (arrowheads highlight the muscularis mucosae). Ulcerations, in contrast to erosions, extend through the mucosa and involve at least the submucosa.

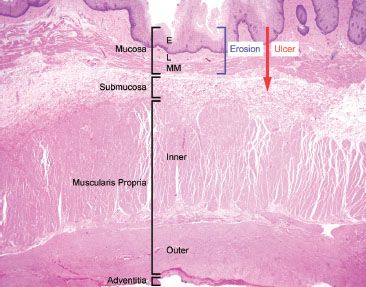

Figure 1.23 Erosion versus ulceration. This resection specimen illustrates the compartments of the esophageal wall. Note that erosions are limited to the mucosa (epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae), while ulcerations extend through the mucosa into at least the submucosa.

PEARLS & PITFALLS

The distinction between erosion and ulceration occasionally presents a point of confusion. Erosions are denudations limited to the mucosa (epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae). Characteristically erosions are accompanied by a rind of fibrin and inflammatory debris, allowing distinction of a true erosion from an artifactual epithelial denudation that occurs with aggressive tissue handling. In contrast, ulcerations extend through and beyond the muscularis mucosae and involve at least the submucosa (Figs. 1.22 and 1.23).

GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GERD)

GERD is a common cause of inflammation of the distal esophagus epithelium, caused by reflux of the acidic gastric contents into the tubular esophagus, discussed in detail in GERD subsection, Lymphocytic Pattern, this chapter. Histologically, it is comprised by a constellation of features, including dilatation of intercellular spaces, basal hyperplasia, elongation of the vascular papillae, intraepithelial eosinophils, vascular lakes, increased intraepithelial T lymphocytes, and balloon cells (epithelial cells with abundant pale cytoplasm). Of these features, dilation of intercellular spaces was most consistently reported, seen in 41% to 100% of patients with GERD and 0% to 30% of control patients.1 Papillary elongation is also a prominent finding, seen in up to 85% of those with GERD and 20% of control patients. GERD can further be stratified into three categories to more accurately describe the degree of pathology: Mild (subtle findings, including rare intraepithelial eosinophils), moderate (conspicuous findings), or marked GERD (striking findings) (Figs. 1.24–1.32). GERD is important to recognize owing to its association with strictures, Barrett mucosa, and malignancy. At this time there are no official consensus recommendations on biopsy protocol for GERD uncomplicated by Barrett esophagus or eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Treatment typically includes lifestyle modification and proton-pump inhibitors, with surgical procedures reserved for severe, refractory cases.

KEY FEATURES OF GERD (some, not all, of the following features are required):

• Dilatation of intercellular spaces

• Basal hyperplasia, >15% of epithelial thickness

• Elongation of the vascular papillae, top half of epithelium thickness

• Intraepithelial eosinophils

• Vascular lakes

• Increased intraepithelial T lymphocytes (squiggle cells)

• Balloon cells (epithelial cells with abundant pale cytoplasm)

Figure 1.24 Balloon cells (arrowheads). Balloon cells are seen throughout this biopsy as large squamous cells with abundant pale eosinophilic/smudgy cytoplasm.

Figure 1.25 Balloon cells. This example shows the balloon cells’ smudgy cytoplasm is similar to frosted glass.

Figure 1.26 Balloon cells. Higher power of previous figure.

Figure 1.27 Mild GERD. The descriptor “mild” can be used in GERD cases with rare intraepithelial eosinophils (arrowhead). Also depicted are basal hyperplasia and vascular papillae elongation.

Figure 1.28 Mild GERD. In this example, a single degranulated intraepithelial eosinophil is identified (arrowhead) along with mild basal hyperplasia.

Figure 1.29 Moderate GERD refers to more conspicuous GERD histologic changes. This case shows more readily identifiable intraepithelial eosinophils (no arrowhead is needed to appreciate the scattered intraepithelial eosinophils). Also note the basal hyperplasia&emdash;the basal 12 layers are expanded from the 1 to 2 cell thickness expected in a normal esophagus.

Figure 1.30 Moderate GERD. The easily identified intraepithelial eosinophils, basal hyperplasia, and elongation of vascular papillae meet the criteria for GERD. However, the findings are nonspecific and in the absence of clinical information, eosinophilic diseases of the esophagus should be considered.

Figure 1.31 Marked GERD shows striking histologic changes, easily appreciated at low power, as in this case. This epithelium is “too blue” due to the prominent basal hyperplasia. In addition, the vascular papillae are approaching the midpoint of the thickness (papillae should normally be confined to the lower third of the epithelial thickness). Eosinophils are abundant. Amyloidosis is also seen (arrowhead).

Figure 1.32 Marked GERD.

FAQ: Could the findings in Figure 1.32 represent eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) instead of marked GERD?

Answer: Absolutely. It is clinically important to distinguish EoE from GERD because of differing etiologic specific therapies. In general, features favoring EoE include superficial eosinophilic microabscesses, eosinophil counts greater than 50/HPF, and basal hyperplasia greater than 50%. Since an unmapped biopsy of EoE can be histologically indistinguishable from GERD, clinicopathologic correlation and mapping of tandem proximal and distal esophageal biopsies are necessary to more definitively distinguish EoE from GERD. See also Eosinophilic pattern, this chapter.

INFECTIONS

Candida Esophagitis

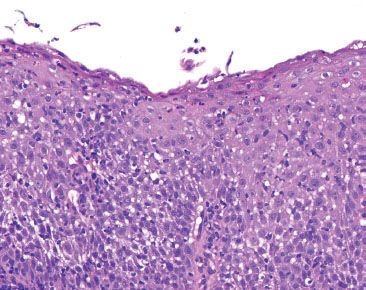

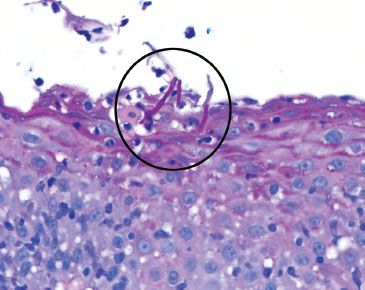

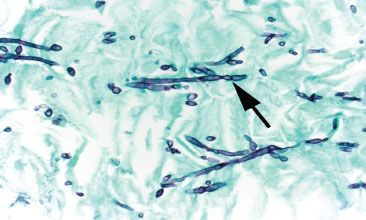

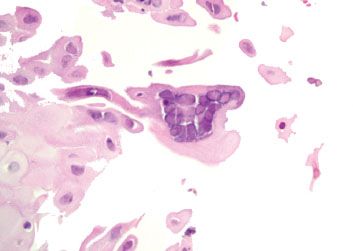

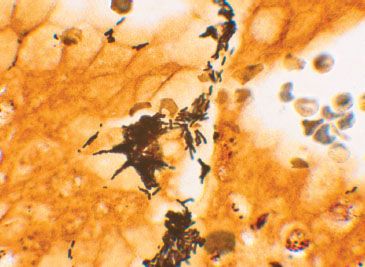

Candida esophagitis appears endoscopically as scattered yellow plaques, patches, exudates, and ulcerations (Figs. 1.33–1.34). These endoscopic appearances can overlap with those of glycogenic acanthosis, esophageal leukoplakia/epidermoid metaplasia, lichen planus/“lichenoid” pattern, making correlation with biopsy findings essential to arrive at the correct diagnosis. Brushing samples sent to the microbiology or cytology laboratories may be more sensitive than biopsies alone.2,3 A history of HIV/AIDS is an important red flag to this diagnosis. In one study of 110 patients with HIV, 51.8% of patients were found to have candidiasis.3 The plaques histologically correlate with desquamated debris, which can coalesce to form extensive exudates and/or ulcerations in severe cases (Fig. 1.34).4 Histologically, acute inflammation in the squamous epithelium and hyperkeratosis are red flags and prompt a thorough high-power examination for the pseudohyphae forms characteristic of candidiasis (Figs. 1.35 and 1.36). Importantly, a complete absence of inflammation can be seen in immunosuppressed patients. A low threshold for ordering special stains such as PAS/D or Grocott methenamine-silver stain (GMS) is advised (Fig. 1.37). See also Parakeratotic pattern, this chapter.

Figure 1.33 Candida esophagitis often appears as scattered yellow plaques on endoscopy.

Figure 1.34 Candida esophagitis. In severe cases of candida esophagitis, the plaques coalesce to form confluent exudates and ulceration, as in this case.

Figure 1.35 Candida esophagitis. This biopsy is “too blue” because of marked inflammation and reactive squamous epithelium. Acute inflammation in the esophagus is often caused by GERD, but should also serve as a red flag to search carefully for Candida and viral cytopathic effect.

Figure 1.36 Candida esophagitis. Indeed, the diagnostic fungal forms were identified with a PAS/AB (magenta, circle). They would appear black on GMS.

FAQ: Do budding yeast signify Candida esophagitis?

Answer: No. Budding yeast often represent oral contamination. Pseudohyphal forms, in contrast, signify tissue invasion and are required for the diagnosis of Candida esophagitis.

Figure 1.37 Candida esophagitis (GMS). True hyphae are defined by the presence of septa, an uncommon finding in Candida. Pseudohyphae, in contrast, are composed of budding yeast-like forms (blastoconidia) joined end to end. The constrictions formed by the buds give the appearance of septations (pseudohyphae) (arrow).

FAQ: How are PAS, PAS/AB, or GMS special stains utilized in the evaluation of pseudohyphae?

Answer: PAS, PAS/AB, and GMS special stains highlight fungal forms and are advised in the following cases, assuming the fungal forms are not present on H&E:

• Clinical impression of candidiasis

• Striking acute inflammation

• Prominent parakeratosis

• Refractory GERD or EoE

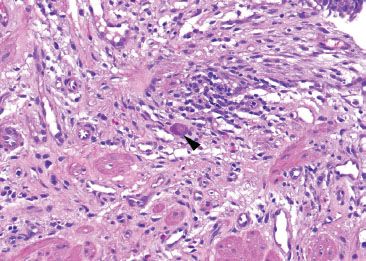

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

KEY FEATURES of CMV Esophagitis:

• Endoscopic findings are typically linear, serpiginous ulcerations with a propensity for the distal esophagus (Fig. 1.38)

• CMV viral cytopathic effect can be seen in endothelial cells, columnar epithelium, and stromal cells; biopsy of the ulcer base is critical for complete evaluation

• CMV viral cytopathic effect includes nuclear and cellular enlargement, smudged chromatin, and nuclear (“owl’s eye”) and/or cytoplasmic inclusions

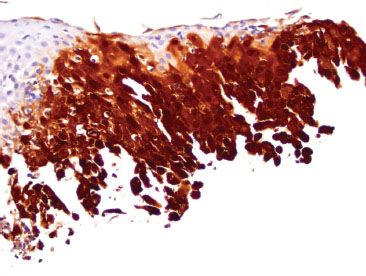

• The inflammatory backdrop shows a prominence of mononuclear inflammation (Figs. 1.39–1.44)

Figure 1.38 CMV esophagitis. Discrete erosive changes and ulcerations are seen in the distal esophagus. These ulcers sometimes coalesce to broadly involve large regions of the esophagus, although small solitary ulcers are most commonly found.

Figure 1.39 CMV esophagitis. CMV viral cytopathic effect is identified with nuclear and cytoplasmic viral inclusions (arrowhead) and is sufficient for the diagnosis of CMV esophagitis: A CMV immunostain was not required for this diagnosis.

Figure 1.40 CMV esophagitis. Higher power of previous figure. Note the characteristic smudgy nuclear and coarse cytoplasmic inclusions with a deep magenta tinctorial quality.

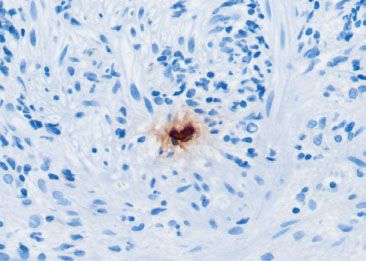

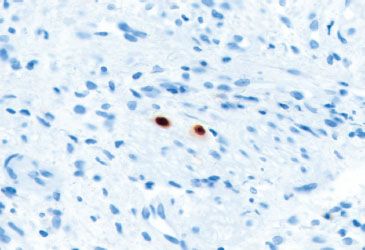

Figure 1.41 CMV esophagitis (CMV immunostain). Although the H&E impression was diagnostic of CMV infection, less obvious cases often require a CMV immunostain. Note the nuclear reactivity in a large (“megalic”) cell.

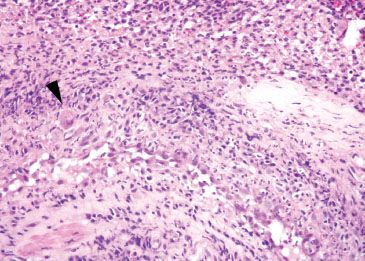

Figure 1.42 CMV esophagitis (arrowhead). The affected cells are “megalic” or enlarged at low power and typically found in the endothelial or stromal cells at the ulcer base. The background shows prominent mixed inflammation with reactive endothelial cells, important red flags to the diagnosis.

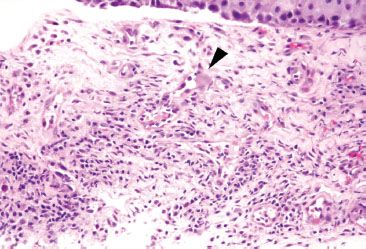

Figure 1.43 CMV esophagitis. In this example, the indicated cell (arrowhead) is a markedly enlarged endothelial cell with prominent glassy and smudged cytoplasm. The features are highly suspicious for CMV infection but the nuclear detail is unclear and the characteristic deep magenta inclusion is not seen in this plane.

Figure 1.44 CMV esophagitis (CMV immunostain). Although CMV immunostains can be tricky to evaluate when there is high background or a suboptimal specimen, look for nuclear reactivity in “megalic” cells, as seen in this case.

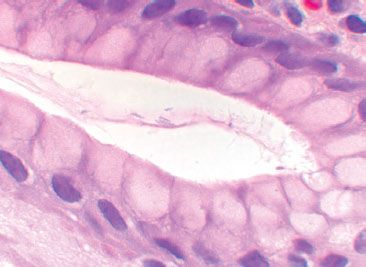

Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

KEY FEATURES of HSV Esophagitis:

• Endoscopic findings include well-circumscribed ulcerations with raised yellow edges (“volcano ulcers”) which can be seen in any region of the esophagus (Fig. 1.45)

• HSV infects squamous epithelium; biopsy of the edge of the ulcer is recommended to ensure squamous epithelium is present5

• The classic nuclear features include molding of nuclear contours, margination of chromatin, and multinucleation (referred to as the “three M’s”) (Figs. 1.46–1.55)

• Cowdry A: Intranuclear inclusions with a clear halo

• Cowdry B: Intranuclear inclusions lacking a clear halo

PEARLS & PITFALLS

In Figure 1.49, the subtle HSV diagnosis could be easily overlooked if the “rule-out EoE” request narrowed the evaluation to counting eosinophils only, rather than taking a more open, systematic approach to the tissue. This case highlights the importance of always looking for the second and less obvious diagnosis. While examining the requisition is always worthwhile, it is more important to avoid being blinded by the history and endoscopic findings.

Figure 1.45 HSV esophagitis. This endoscopic image shows ulcerations, patchy erosions, and white exudates. HSV cannot be reliably distinguished from CMV or Candida by endoscopic evaluation. A complete evaluation should therefore include biopsy of the ulcer base (for CMV) and ulcer edge (for HSV).

Figure 1.46 HSV esophagitis. An HSV immunostain is not necessary because the classic diagnostic features are present (the three “M’s”): (1) Molding of nuclear contours; (2) margination of chromatin to the periphery of the nucleus resulting in a pale nuclear center and darkened peripheral rim; (3) multinucleation.

Figure 1.47 HSV esophagitis. This case of acute esophagitis features a rare cell suspicious for HSV viral cytopathic effect with multinucleation and equivocal molding (arrowhead). Since similar findings are occasionally seen in degenerating, reactive squamous cells, an HSV immunostain was performed.

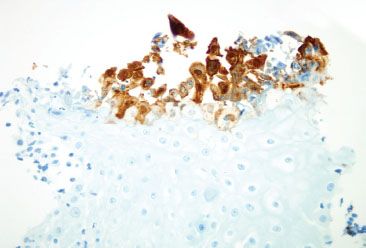

Figure 1.48 HSV esophagitis (HSV immunostain). The corresponding HSV immunostain highlights more virally infected squamous epithelium than apparent on H&E.

Figure 1.49 HSV esophagitis. This case was from a patient with a history of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), although characteristic features of EoE are not seen in this field. Note the subtle viral cytopathic effect in the basal aspect of the squamous epithelium (arrowheads highlight nuclear molding and chromatin margination).

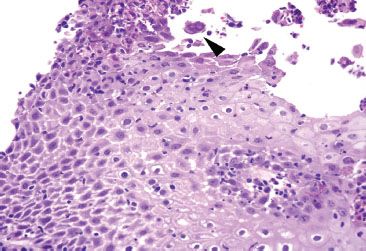

Figure 1.50 HSV esophagitis. Subtle viral cytopathic effect is seen in the lateral aspects of this specimen and in the free-floating fragment at the top right.

Figure 1.51 HSV esophagitis. Careful examination of ulcer debris can provide valuable clues to the etiology of the ulcer. In this example, viral cytopathic effect diagnostic of HSV esophagitis is identified within the ulcer debris. Numerous multinucleated cells show molding of nuclear contours and margination of chromatin. An HSV immunohistochemical stain is not necessary for these unequivocal morphologic features.

Figure 1.52 HSV esophagitis. This example shows a rare cell with equivocal HSV viral cytopathic effect (arrowhead) and background ulceration (not shown).

Figure 1.53 HSV esophagitis (HSV immunostain). The corresponding HSV immunostain confirms HSV esophagitis, and emphasizes that a low threshold for CMV, HSV, and PAS stains is prudent in the case of esophageal ulcerations.

Figure 1.54 HSV esophagitis. Cells suspicious for HSV viral cytopathic effect are seen at the base.

Figure 1.55 HSV esophagitis (HSV immunostain). The corresponding HSV immunostain highlights the virally infected cells.

FAQ: Does HSV2 infection in a child imply sexual activity/abuse?

Answer: No. Historically, the HSV1 serotype has been associated with oral ulcerations and HSV2 with genital ulcerations. Studies that are more recent suggest these historic associations may no longer be relevant.6,7 As a result, it is not necessary to routinely determine serotypes nor to suggest sexual abuse for HSV2 reactive cases, although the testing is technically feasible with HSV1- or HSV2-specific immunohistochemical stains or molecular-based assays.

FAQ: Does a positive HSV immunohistochemical stain exclude varicella-zoster virus (VZV)?

Answer: No. VZV is the causative agent of varicella (chickenpox) and herpes zoster (shingles). Both HSV and VZV belong to the Herpesviridae family, show identical viral cytopathic effect, and react identically with an HSV immunohistochemical stain. HSV can be distinguished from VZV by a specific VZV immunohistochemical stain, culture methods, or molecular assays.

FAQ: How are CMV, HSV immunostains utilized?

Answer: If the diagnosis can be made on H&E due to classic viral cytopathic effect, additional immunostains are not necessary. However, a low threshold for requesting CMV and HSV immunostains (and fungal special stains) is recommended in the setting of esophageal ulcerations because the diagnostic features can be easily obscured by the intense background inflammation.

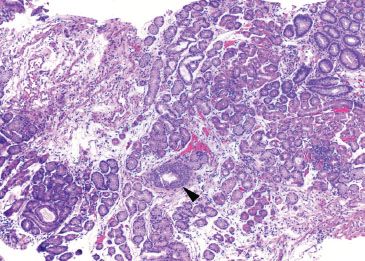

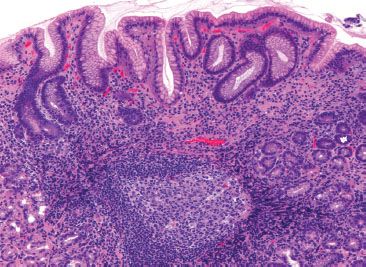

Helicobacter

Whereas acute inflammation in the esophagus is most associated with GERD, inflamed cardia biopsies (which can be present in biopsies containing esophagus) are associated with Helicobacter infections in the majority of cases (78% to 97.7%).8,9 The concept of the cardia as a normal anatomic landmark is debated but, in general, the cardia is defined as the small segment of stomach between the distal esophagus and proximal stomach with oxyntic mucosa. Red flags to the diagnosis of Helicobacter infection include recognition of acute and chronic inflammation, superficial lymphoplasmacytosis, and lymphoid aggregates (Figs. 1.56–1.61), as discussed in detail in Acute Gastritis, Stomach chapter.

Figure 1.56 Helicobacter. Esophageal biopsies with columnar mucosa offer an opportunity to make additional diagnoses, such as Helicobacter carditis, as in this case. On low power, the active chronic inflammation, prominent lymphoid aggregate with a well-formed germinal center, and superficial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation strongly suggest Helicobacter infection.

Figure 1.57 Helicobacter pylori. The organisms were found in mucin-rich foci (arrowheads) and in gland lumina (not shown). Their wide one-and-a-half-turn spiral gives them a slightly bent appearance.

Figure 1.58 Helicobacter pylori (Diff-Quik). A Diff-Quik special stain highlights the Helicobacter pylori organisms (special stains are not necessary if the organisms are apparent on H&E).

Figure 1.59 Helicobacter pylori (Warthin–Starry). A Warthin–Starry special stain highlights the Helicobacter pylori organisms. This silver-based stain coats the organisms, making them slightly larger and easier to identify than the previous Diff-Quik stain.

Figure 1.60 Helicobacter heilmannii organisms are more slender and tightly spiraled than Helicobacter pylori organisms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree