Esophagitis

Introduction

Esophagitis is one of the most common findings encountered during transnasal esophagoscopy (TNE). It has several etiologies, including acid reflux, foreign bodies (e.g., pills), infection, allergy, caustic injury, as well as a sequela of radiation therapy.

Reflux Esophagitis

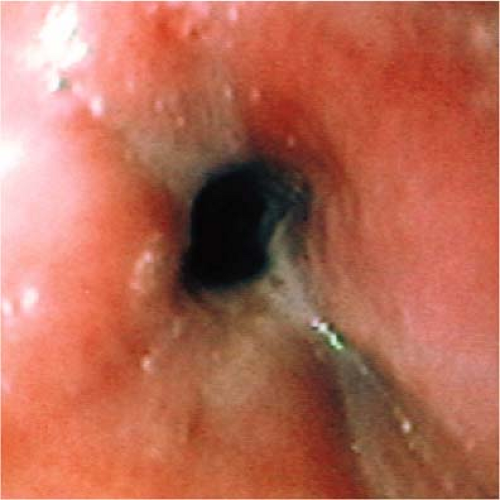

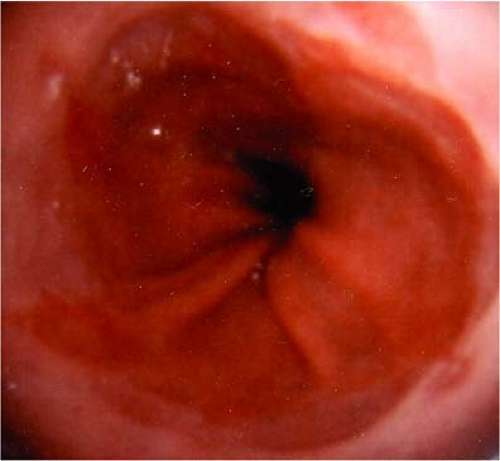

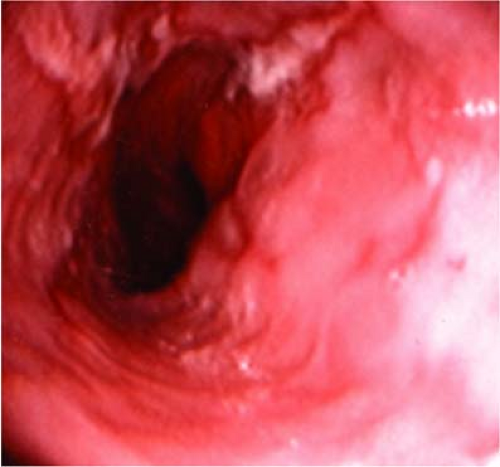

The ability to consistently describe the endoscopic findings in a patient with suspected reflux esophagitis is important. Although there are several grading systems for esophagitis, the Los Angeles (LA) classification system is the most widely accepted (1). The LA classification system is based on the extent of esophageal mucosal breaks seen endoscopically. A mucosal break is defined as an area of slough or an area of erythema with a discrete line of demarcation from the adjacent or normal-looking mucosa. The mucosal breaks are then classified by a grading scale: A, B, C, and D (2). The reference point used in determining the extent of the mucosal break is the peak of the mucosal folds in the esophagus, best seen during partial air insufflation of the esophagus. In grade A esophagitis, the mucosal breaks are less than 5 mm in length and do not extend between the tops of two esophageal mucosal folds (Fig. 4.1). With grade B esophagitis, the mucosal breaks are longer than 5 mm, but confined to the mucosal fold of the esophagus, so that they are not contiguous between the tops of the two mucosal folds (Fig. 4.2). In grade C esophagitis, the mucosal breaks are continuous between the tops of two or more mucosal folds but less than 75% of the esophageal circumference (Fig. 4.3). In grade D esophagitis, the mucosal break involves at least 75% of the circumference of the esophagus (Fig. 4.4). As esophagitis becomes more severe, complications of esophagitis may ensue, such as stricture. An esophageal stricture is defined as a circumferential narrowing of the esophagus (Fig. 4.5).

Candida Esophagitis

Esophagitis caused by Candida albicans is the most common infectious cause of esophagitis (3). The most commonly reported symptoms are odynophagia and dysphagia, though up to 25% of patients can be asymptomatic (4). Some individuals, however, will present with symptoms suggestive of laryngopharyngeal reflux such as globus, excessive throat clearing, or excessive mucous. Risk factors for the development of Candida esophagitis include the presence of HIV infection, postradiation or chemotherapy, diabetes mellitus, steroid use, and diseases of impaired esophageal peristalsis such as progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). It is important to note that a normal flexible laryngoscopy and oropharyngeal examination do not eliminate the possibility of fungal esophagitis. We have seen dozens of patients who are immunocompetent and not using steroids with Candida esophagitis and no significant physical findings in the laryngopharynx.

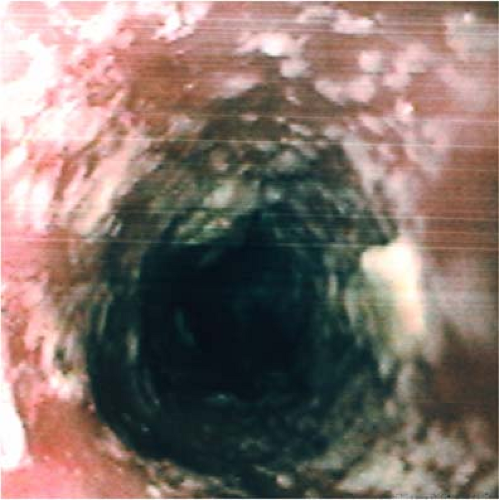

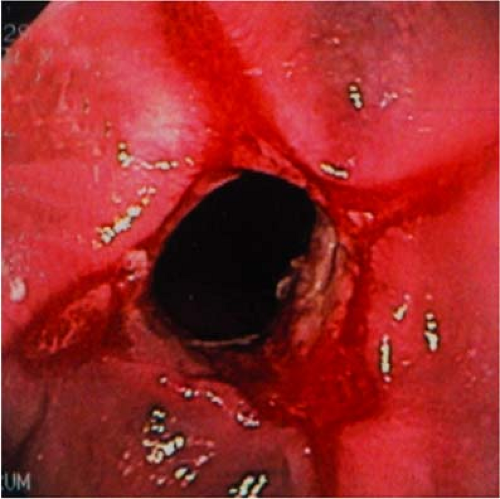

The endoscopic appearance of Candida esophagitis is characterized by mucosal plaques, often punctate, typically yellow to tan (Fig. 4.6). As the disease increases in severity, the scattered mucosal plaques begin to coalesce, ultimately resulting in a circumferential coating

of the mucosa. With disease progression, the plaques themselves can narrow the esophageal lumen (Fig. 4.7) (5).

of the mucosa. With disease progression, the plaques themselves can narrow the esophageal lumen (Fig. 4.7) (5).

Figure 4.1 Grade A esophagitis. The mucosal breaks are less than 5 mm in length and do not extend between the tops of two mucosal folds. |

Figure 4.2 Grade B esophagitis. The mucosal breaks longer than 5 mm are confined to the mucosal fold, i.e., not contiguous between the tops of the two mucosal folds. |

Figure 4.3 Grade C esophagitis. The mucosal breaks are continuous between the tops of two or more mucosal folds, but less than 75% of the esophageal circumference. |

Figure 4.4 Grade D esophagitis. The mucosal break involves at least 75% of the circumference of the esophagus. |

Ulceration from Candida esophagitis is very rare. When ulceration is seen, consideration for concomitant viral etiologies should be made, most commonly cytomegalovirus (5). Under the plaque, the mucosa is inflamed but without true ulceration. The infection generally remains limited to the superficial epithelium as a result of repeated shedding of the epithelium into the esophageal lumen. Histopathologic diagnosis is made by identification of yeast and mycelial forms typical for Candida. Treatment consists of topical antifungal agents such as nystatin and systemic antifungal agents such as fluconazole.

Herpes Esophagitis

Esophagitis due to herpes is the most frequent viral etiology of esophagitis. While herpes esophagitis typically presents in immunocompromised hosts, it also occurs in immunocompetent individuals. Squamous epithelium is the primary target of the herpes virus, so in the gastrointestinal tract, the esophagus is preferentially affected. Approximately 20% of patients with herpes esophagitis have concomitant oropharyngeal lesions (6). The most common presenting symptom is acute onset of severe odynophagia and dysphagia, with inability to handle secretions. The dysphagia resulting from herpes esophagitis can resemble dysphagia from acute cerebrovascular disease with the inability to handle secretions and drooling and can be

severe enough to warrant nonoral means of nutritional support. Endoscopy reveals multiple, shallow ulcerations with raised, heaped-up edges, sometimes forming a large series of ulcers (7,8). The distal one third of the esophagus is most commonly affected. Biopsy of the edge of the ulcer assists in making the diagnosis, though tissue viral culture sometimes is necessary. Herpes esophagitis can be treated with acyclovir, though it can resolve spontaneously.

severe enough to warrant nonoral means of nutritional support. Endoscopy reveals multiple, shallow ulcerations with raised, heaped-up edges, sometimes forming a large series of ulcers (7,8). The distal one third of the esophagus is most commonly affected. Biopsy of the edge of the ulcer assists in making the diagnosis, though tissue viral culture sometimes is necessary. Herpes esophagitis can be treated with acyclovir, though it can resolve spontaneously.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree