Esophageal Infections

The esophagus is rarely infected in immunocompetent persons but is a common site of infection in patients with immune defects. Normal host defenses of the esophagus are the salivary flow, an intact mucosa, normal esophageal motility, and normal gastric acidity with the absence of excessive gastroesophageal reflux.

Humoral immunity including secretory IgA is important in protecting the mucosal integrity. However, based on the observation that patients with neutropenia and obvious defects in cell-mediated immunity have higher rates of esophageal infections, it seems likely that a major protective mechanism in the esophagus is cell-mediated immunity.

The esophagus can be involved with infections by bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Most esophageal infections are fungal (Candida albicans) or viral (herpes simplex virus [HSV] or cytomegalovirus) or a combination of the two. Diagnosis of the specific etiologic agent is essential because of the availability of effective antiviral, antifungal, and antibacterial therapy.

I. FUNGAL ESOPHAGITIS.

C. albicans is the most common fungus recovered from patients with fungal esophagitis. However, other species have been isolated and implicated as etiologic agents of such infections. These are Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida glabrata, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Aspergillus, and Torulopsis glabrata.

C. albicans is found in the oropharynx of approximately 50% of the healthy population. It is also found in the skin and the bowel of immunocompetent persons. Patients with defects in cellular immunity and those treated with antibiotics may have sufficient alteration in their normal bacterial flora to have luminal candidal overgrowth. It is thought that patients with physical or chemical damage to the esophageal mucosa (e.g., acid reflux) may be at increased risk for developing candidal overgrowth and subsequent invasive disease. Indeed, the worst lesions visible in many instances of Candida esophagitis are in the distal esophagus, the area most likely to suffer from reflux damage.The mechanisms responsible for permitting mucosal adherence and subsequent invasion are unknown.

Candidiasis is by far the most common esophageal infection. In fact, it is a rather common disease with a varying spectrum of severity. It can be an asymptomatic incidental finding during endoscopy as well as an overwhelming infection causing death. In one study, 90% of the HIV-infected patients with oral thrush who underwent endoscopy had mucosal lesions caused by Candida. Larger series have not confirmed this high figure; however, many of the treatments effective for oral thrush are also effective in most instances of Candida esophagitis, suggesting that diagnostic evaluation such as endoscopy might best be reserved for patients who do not respond to initial topical antifungal therapy.

In addition to acute manifestations of the disease, late sequelae can develop. Mucosal sloughing caused by an intense inflammatory response, esophageal perforation, and stricture formation have been reported.

While Candida esophagitis can occur in any patient, certain conditions seem to predispose to it.

A. Predisposing factors.

These factors include HIV infection, neutropenia, hematologic and other malignancies, organ transplantation, and immunosuppressive agents including corticosteroids, antineoplastic chemotherapy, radiation therapy, broad-spectrum antibiotics, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, alcoholism, malnutrition, old

age, and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC). In CMC, esophageal candidiasis may occur in addition to the chronic involvement of the nails, skin, and oral cavity. These patients have defective cellular immunity. However, since the wide use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of opportunistic infections has been drastically reduced.

age, and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC). In CMC, esophageal candidiasis may occur in addition to the chronic involvement of the nails, skin, and oral cavity. These patients have defective cellular immunity. However, since the wide use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of opportunistic infections has been drastically reduced.

B. Diagnosis

1. Clinical presentation

a. Dysphagia and odynophagia. The most common symptoms of esophageal candidiasis are dysphagia and odynophagia; fever may be present. Pain may be substernal and radiate to the back. In some patients, odynophagia may be experienced only when they drink hot or cold beverages, and in others, it may be so severe that they may not be able to eat at all. The symptoms may be absent in 20% to 50% of the patients, especially those with mild infection, patients who are severely debilitated, and those with CMC.

b. Oral thrush may be present in children and in HIV-infected individuals with esophageal candidiasis, but it is usually absent in immunocompetent adults. The plaques adhere to the underlying mucosa but can be dislodged at endoscopy revealing an inflamed, friable mucosa underneath. Candida can coexist with other pathogens in up to 30% of patients, and reliance on the endoscopic appearance alone may result in failure to identify a concomitant viral or bacterial infection. Multiple biopsies are essential to exclude coexisting disorders. During endoscopy, mucosal lesions should be brushed and submitted for cytologic evaluation and biopsied for histologic examination. Cytologic examination of brushings is more sensitive than histologic examination of the biopsy specimens since organisms may be washed off the mucosa in superficial Candida infections during the processing of the biopsy specimens.

In addition to cytologic evaluation, material obtained from esophageal brushings may be placed on a microscopic slide, and a drop of potassium hydroxide may be added to lyse the epithelial cells. Both yeast and hyphae of C. albicans can be demonstrated in this manner. Because mycelia are not found in the normal esophagus, their presence in the brushings strongly suggests the diagnosis. A Gram’s stain of esophageal brush specimens can also demonstrate the presence of yeast, hyphae, and bacteria.

Biopsy specimens should be stained with hematoxylin-eosin to assess the severity of the inflammation. Silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains of biopsy specimens may confirm the presence of fungal elements.

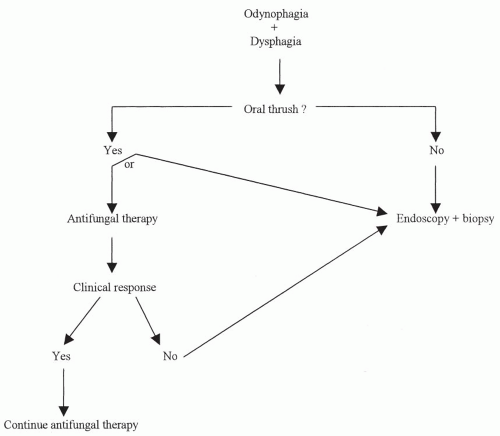

In patients with AIDS, concomitant infection with viruses (e.g., cytomegalovirus, HSV) may be present. Cytoplasmic and nuclear inclusion bodies and other findings suggestive of viral infection also should be looked for in both biopsy and brush specimens. Figure 19-1 is an algorithm that may be used as a diagnostic approach.

2. Diagnostic studies

a. Endoscopy. Fiberoptic endoscopy is the most useful method in the diagnosis of Candida esophagitis. Direct observation of the esophageal mucosa may allow the differentiation of Candida esophagitis from other infections (e.g., herpes) and from varices, carcinoma, or peptic disease, which may have a similar radiologic picture. The endoscopic appearance of esophageal candidiasis is graded on a scale from I to IV. The lesions range from small raised white plaques to ulceration and confluent plaque formation appearing as friable pseudomembranes.

b. Radiologic studies. If a barium swallow is performed, the esophagram is normal in most patients. When radiologic abnormalities are found, the infection is usually severe. A double-contrast esophagram may increase the yield of positive findings. The esophagus usually has a “shaggy” appearance due to superficial ulcerations, but deep ulcerations may also be present. Abnormal motility with diminished peristalsis and occasional spasm may be seen. Esophageal stricture is commonly present in CMC. This may be a focal narrowing in the upper esophagus or may involve the entire length.

C. Treatment

1.

Before the initiation of any specific therapy for esophageal candidiasis, the underlying predisposing factor should be identified.

2.

Patients with AIDS and mild-to-moderate symptoms who have oral thrush may be treated initially with one of the topical agents such as nystatin (Mycostatin) suspension, clotrimazole troches, or one of the “azoles” may be an alternative form of therapy before undergoing a diagnostic procedure (Table 19-1).