The history of esophageal cancer dates back to ancient Egyptian times, circa 3000 bc . Since then, the progress in the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal cancer has been steady. Over the last few centuries there have been advancements in the visualization and removal of these lesions, but with no real overall impact on survival rates. The twenty-first century is the time to make major progress in not only improving survival rates, but also in diagnosing esophageal cancer in the very early stages.

In the history of esophageal cancer, the majority of initial discoveries were made in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. However, the earliest mention of esophageal cancer appears to have come from Egypt around 3000 bc , and there were further reports from China around 2000 years ago. Then, between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, there were advancements in the visualization and removal of these lesions. In the twentieth century these techniques were improved upon, but with no real increase in survival rates. Currently, the technological instruments and treatment options available are amazing when compared with even 50 years ago, but the majority of cases are still diagnosed at late stage and there has been no substantial overall improvement in outcomes from this insidious disease. The literature is scattered and can be extremely difficult to locate; as such, this article focuses on a few key historical moments associated with esophageal cancer diagnosis and treatment. Box 1 shows a historical timeline of esophageal cancer.

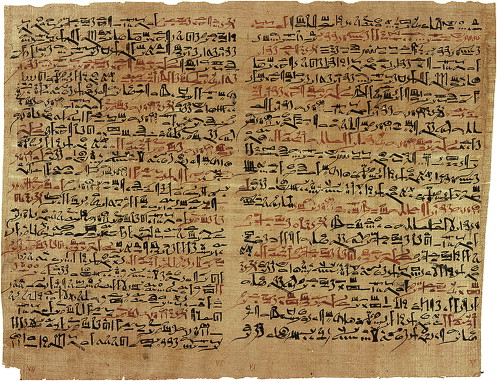

3000–2500 bc: “Smith Surgical Papyrus” describes repair of the “gullet” after perforation; however, no mention of cancer.

- 950

bc: The Greek terms for “esophagus” and “stomach” appear in Homeric literature.

ad 0–1: The Chinese describe “swallowing syndromes” caused by cancer.

131–200: Galen describes fleshy growths causing obstruction of the gullet.

11th Century: Avicenna discusses the causes of dysphagia, including tumor involvement.

1363: Chauliac describes foreign bodies in the esophagus.

1543: Vesalius describes the anatomy of the esophagus.

16th Century: J. Fernel writes of scirrhus and other tumors blocking the esophageal tube and causing difficulty in swallowing.

1592: Fabricius Aquapendente employs wax tampers to remove foreign bodies from the esophagus.

1674: T. Willis uses whale bone to dilate the esophagus.

1724: Boerhaave reports a case of spontaneous rupture of the esophagus.

1764: Ludlow describes a pharyngesophageal diverticulum.

1806: Bozzini develops an early endoscope using a mirror and reflected light from a candle in an attempt to see the upper esophagus.

1809: Pinel recommends the use of esophageal tubes to feed the insane.

1821: Purton describes a case of esophageal achalasia.

1822: Magendie notes that food is held up at the lower end of the esophagus, suggesting the presence of a sphincter.

1843: Switzer invents the esophageal dilators.

1844: The first recorded operation of esophagotomy for the relief of esophageal stricture by John Watson an American surgeon.

1857: Albrecht Theodor Von Middeldorpf, a Breslau surgeon, performs the first operation on a tumor of the esophagus.

1868: Kussmaul is the first to pass a lighted tube through the entire esophagus into the stomach.

1871: Billroth successfully resects and reanastomoses the cervical esophagus in dogs.

1872: First excision of the esophagus in man, performed by Christian Albert Theodor Billroth, an Austrian surgeon.

1877: Czerny is the first to successfully resect the cervical esophagus for carcinoma in human beings.

1881: Mikulicz studies the physiology of the esophagus.

1883: Esophageal motility in human beings is determined by H. Kronecker and S. Meltzer with pressure measurements of inserted balloons.

1886: J. Mikulicz treats esophageal carcinoma by resetion and plastic reconstruction.

1898: Rehn attempts resections of an esophageal carcinoma via right posterior mediastinotomy in two patients, unsuccessfully.

1901: Dobromysslow successfully performs the first intrathoracic resection and reanastomosis of the esophagus in dogs.

1905: Beck describes formations of a gastric tube from the greater curvature of the stomach, based on the gastroepiploic artery.

1907: Wendell describes transpleural resection of an esophageal carcinoma of the lower esophagus with lateral esophagogastrostomy in a lumen (patient dies the following day).

1908: Volecker successfully resects a carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction with primary esophagogastrostomy via laparotomy.

1913: Zaaijer successfully resects a carcinoma of the cardia via an abdominothoracic approach.

1913: Torek, using a transthoracic approach, is the first to successfully resect an esophageal carcinoma.

1933: Oshawa resects the thoracic esophagus for carcinoma with immediate esophagogastrostomy (8 of 18 patients survive).

1938: Adams is the first surgeon in the United States to perform transthoracic esophageal resection with immediate esophagogastrostomy.

1946: Ivor Lewis introduces esophagectomy and esophagogastrostomy through a right thoractomy.

1947: Sweet completes 212 resections for esophageal carcinoma (17% operative mortality and 8% 5-year survival).

1950: N.R. Barrett reviews what is now called Barrett’s esophagus, previously reported by W. Tileston (1906), A. Lyall (1937), and P.R. Allison (1943). The complication of adenocarcinoma is noted by B.C. Morson and J.R. Belcher (1952).

1954: C.A. Clarke and R.B. McConnell connect the occurrence of tylosis and carcinoma of the esophagus.

1954: L.R. Celestin develops an esophageal tube widely used for the relief of malignant dysphagia.

1963: Logan describes 853 resections for esophageal carcinoma (29% operative mortality).

1970: C.F. Pope determines the histologic changes of reflux esophagitis obtained on endoscopy.

1971: A. Vanderwonden document the dysplastic transformation of Barrett’s esophagus.

1978: Orringer and Sloan revive the technique of Gray Turner’s “esophagectomy without thoracotomy.”

1982: D. Fleischer employs endoscopic laser therapy to palliate cases of esophageal carcinoma.

1984: Leichman and colleagues at Wayne State University combine 3,000 cGy with two cycles of 5-FU and cisplatin preoperatively in 21 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (37% pathologic complete response; operative mortality 27%).

1997: Multiple phase III randomized trials fail to show significant survival benefit for neoadjuvant multimodality therapy.

21st Century: New endoscopy techniques, new types of chemotherapy, advances in radiological instruments and improvements in surveillance.

Adapted from Lee RB, Miller JI. Esophagectomy for cancer. Surg Clin North Am 1997;77:1171, with permission.

Ancient times

Egypt

One of the first human written descriptions of disease states including the anatomy, physiology, pathology, and clinical observation was discovered in 1862 by American egyptologist Edwin Smith and is known as the “Smith Surgical Papyrus” ( Fig. 1 ), which was dated to have been transcribed between 3000 and 2500 bc (see Box 1 ). Although there is no specific mention of esophageal cancer in the papyrus, it is worth mentioning case 28 of the 48 cases recorded for historic interest, titled “A Gaping Wound of the Throat Penetrating the Gullet.” The translation of the material, including headings used, is shown below:

Examination

If thou examinest a man having a gaping wound in his piercing through to his gullet; if he drinks water he chokes (and) it come out of the mouth of his wound; it is greatly inflamed, so that he develops fever from it; thou shouldst draw together that wound with stitching.

Diagnosis

Thou shouldst say concerning him: “One having a wound in his throat, piercing through to his gullet. An ailment with which I will contend.”

First treatment

Thou shouldst bind it with fresh meat the first day. Thou shouldst treat it afterwards with grease, honey, (and) lint every day, until he recovers.

Second examination

If, however, thou findst him continuing to have fever from that wound.

Second treatment

Thou shouldst apply dry lint in the mouth of his wound, (and) moor (him) at his mooring stakes until he recovers.

Roman Empire

Galen ( Fig. 2 ), a famous Roman physician and philosopher who lived around ad 125–200, was purportedly the most accomplished medical researcher of the Roman period. His published work on the causes of symptoms mentions the possibility of a fleshy growth partially or entirely obstructing the passage of food down the gullet.

Persian Empire

Avicenna ( ad 980–1037), who is regarded as the father of early modern medicine, also wrote about esophageal cancer ( Fig. 3 ). In one of his published works, titled The Canon of Medicine published in 1025, he suggested that dysphagia was the most important symptom of tumors (apostema) of the esophagus.

China

The earliest reports of esophageal cancer in China appeared over 2000 years ago and were referred to as “Ye Ge,” which means dysphagia and belching. Reports of the disease have been recorded in traditional Chinese medical texts, with some of the authors suggesting that these particular cancers were a result of “heavy indulgence of heated liquors.” Moreover, others stated that esophageal cancer was more commonly seen in the elderly and rarely occurred in young people. In Henan Province, historical records report “dysphagia syndromes” among the inhabitants approximately 2000 years ago. In addition, in Linxian there had been a condition called “ge shi bing” (hard-of-swallowing disease), which has been present for several generations. Esophageal cancer was so feared in ancient times in this region that a temple was erected and it was known as the “Houwang Miao” (Throat-God Temple).

Early modern period

The period from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century saw a dramatic rise in developments related to recognizing and attempting to treat esophageal cancer. The Spanish born Arabian physician Avenzoar (1090–1162), made several ingenious suggestions regarding cases of obstruction or of palsy of the gullet. He recommends treatment options that include “the introduction of food into the stomach by a silver tube and the use of nutritive enemata.” However, Avenzoar did not recommend “support the strength by placing the patient in a tepid bath of nutritious liquids that might enter by cutaneous imbibition.” One of the leading figures in sixteenth century science and medicine was the French born Jean Francois Fernel (1497–1558), who wrote among other volumes, On the Hidden Causes of Things (1548) and J. Fernelii Medicina (1554) ( Fig. 4 ). He described scirrhus and other tumors that blocked the esophagus, causing dysphagia.

In 1691, the surgeon John Casaubon died of esophageal cancer, and he described the symptoms leading up to his death.

At dinner I was almost choaked by swallowing a bit of a roasted mutton which as I thought stuck in the passage about the mouth of the stomach. But it suffered noething to goe downe and the stomach threw all up, though never soe small in quantitie, to all our amazements the sckilfull not knowing what 2 make of my condition. It being an unusuall afflixion wch. my melancholi suggested it an extraordinarie judgment. I could swallow about 2 spoonfulls about half way (as I thought) and then it would flush up in spite of my hart… Some small humidity or drops of what I dranck rather distilld or dropt into the stomach which afforded a bare living nourishment and on a sudden I grew lean as a skeleton and at some tymes very faint and feeble, although I recovered in some measure and had stomach 2 eate, my meate doeth noe gt. good and I am in a kind of atrophie…

From the commencement of the eighteenth century, reports of esophageal neoplasm were generally referred to as polypus, scirrhus, tumor, struma, or cartilaginous esophagus, and their description as either single case reports or case series was on the rise.

The first Western description suggesting a link with a history of heavy drinking and the development of esophageal cancer was made by E.G. Gyser in his 1770 paper titled, “ De fame lethali ex callosa oesophagi angustia .”

The earliest drawings believed in existence of an esophageal neoplasm were published in Matthew Baillie’s ( Fig. 5 ) 1799 edition of Morbid Anatomy ( Figs. 6–8 ). In another book by Alexander T. Monro (1773–1859) titled The Morbid Anatomy of the Human Gullet, Stomach and Intestines , published in 1881, Monro wrote about the treatment of “Scirrhus and cancer in the Gullet.” Moreover, he mentioned the possibility of fatal esophagotracheal communication and was almost certainly the first to describe the topic of the spread of “Scirrhus and Cancer” to and from the gullet. Furthermore, he describes the main symptoms plainly:

Pain and an inability to swallow solids, are the earlier symptoms of this disease, and after a time, even fluids are arrested in their course downwards; they remain for a short time in the Gullet, and distend it, thereby creating a sense of suffocation, until the contents are rejected, by an inverted action of the Gullet, through the nose and mouth, by which the patient is much relieved, and the remainder passes down with a guggling noise, like water flowing through a constricted passage.