The comorbid conditions erectile dysfunction (ED) and depression are highly prevalent in men. Multiple regression analysis to control for all other predictors of ED indicate that men with high depression scores are nearly twice as likely to report ED than nondepressed men. Depression continues to be among the most common comorbid problems in men with ED, both in the community and in clinical samples. This article reviews the current knowledge about the relationship between ED and depression, the effect of treatments for depression on ED, ways to improve screening for depression, and treatment of ED in patients with this comorbidity.

The comorbid conditions erectile dysfunction (ED) and depression are both highly prevalent in men. The National Comorbidity Survey found a lifetime prevalence of major depression of 12.7% for men in a representative sample of the US population, with minor depression affecting an estimated 10% of the population aged 15 to 54 years. In the Massachusetts Male Aging Study, high depression scores were associated with frequent reports of moderate ED (for men aged 40–70 years), with the prevalence of severe, or complete, ED estimated at 10%. Multiple regression analysis to control for all other predictors of ED still found that men with high depression scores were nearly twice as likely to report ED than nondepressed men. Depression continues to be among the most common comorbid problems seen in men with ED, both in the community and in clinical samples.

There is a very low rate of recognition of depression by urologists and other nonpsychiatric physicians. Lee and colleagues determined that 33% of the 120 men presenting to a sexuality clinic had a major current psychiatric disorder. Of these 40 men, only one-third had been identified as having a mental disorder by the study urologist. Major depression was present in 15 (12.5%) of those men and was the second most common category of mental illness (chemical dependence was first). This failure to properly diagnose has 2 obvious negative consequences. First, the mental disorders detected were hardly trivial: 2 of the men required psychiatric hospitalization, 1 made a suicide attempt, and 1 required electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Failure to properly diagnose is in itself serious and could have extremely deleterious consequences. Second, there is a growing body of evidence that underdiagnosed and untreated psychosocial-cultural factors contribute significantly to ED treatment discontinuation and failure. In fact, Mallis and colleagues determined that more than 50% of their study participants reported a lifetime history of psychiatric difficulties, concluding that obtaining a patient’s psychosocial history is essential when evaluating and treating ED.

The effect of depression on the course of ED is multifaceted because of systemic pathophysiologic implications as well as psychological and behavioral ramifications. Although the relative contributions of organic and psychosocial-cultural causes to depression is open to discussion, there is little debate that depression can have a deleterious effect on the treatment of ED. Confounding this problem is the reality that a proper psychiatric diagnosis usually requires a 45- to 90-minute interview by a trained psychiatrist, whereas a urologist’s time is often limited to 15 to 30 minutes, almost all of it occupied with acquiring medical information. This article reviews the current knowledge about the relationship between ED and depression, the effect of treatments for depression on ED, ways to improve screening for depression, and treatment of ED in patients experiencing this common comorbidity.

Every patient who seeks treatment of ED should be screened for a major mood disorder (MMD) or depression. Depression in the medically ill is generally underdiagnosed and undertreated. Patients with ED have an increased likelihood of depression and vice versa. In patients with ED, it is of course normal to have a distressed response to this condition. Indeed, distress or bother is generally a part of the diagnostic criteria for ED. Whereas many of these symptoms resolve themselves with the effective treatment of the ED, for those individuals who have significant depressive disorder (associated with ED rather than caused by ED), this is not the case. Failure to screen for MMD can result in significant risk to the patient in terms of both morbidity and mortality.

What is depression?

ED has been extensively characterized elsewhere. However, before proceeding further, it would be useful to define and characterize depression. It is a significant error to view depression as “only” a psychosocial-cultural phenomenon. A severe major depression is frequently organic in derivation and some think that depression is a systemic disease with distinct subtypes, each with unique organic pathophysiology. Yet, it is clear that behavioral, psychosocial, and cultural factors also play a role in the cause of depression in much the same way they do in sexual dysfunction (SD) generally and ED specifically. Like ED, there are omnipresent psychogenic components existing in most depressed patients regardless of the degree of organicity. The degree of manifest dysfunction frequently exceeds the degree of organic impairment even in men who are “organically ” depressed. In other words, like ED, despite the existence of organic pathogenesis, depression always has a psychogenic component, even if the depression was initially the result of constitution, illness, surgery, or other treatments.

Depressed mood is common in everyday life and may be a normal and expectable reaction to adverse events. However, when depressed mood lasts for 2 weeks or more, is associated with certain other symptoms, such as insomnia and agitation, and causes serious distress or impairment in functioning, a diagnosis of a mood disorder should be considered. The algorithm required and the multiple terms used to diagnose specific mood disorders in the current the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition Text Revision) (DSM-IV-TR) can be confusing for the uninitiated. Box 1 provides the nomenclature used in DSM-IV-TR to categorize the various mood disorders.

Mood episodes

Major depressive episode

Manic episode

Mixed episode

Hypomanic episode

Depressive disorders

Major depressive disorder

Dysthymic disorder

Depressive disorder not otherwise specified

Bipolar disorders

Bipolar I disorder

Bipolar II disorder (recurrent major depressive episodes with hypomanic episodes)

Cyclothymic disorder

Bipolar disorder not otherwise specified

Other mood disorders

Mood disorders due to a general medical condition

Substance-induced mood disorder

Mood disorder not otherwise specified

Specifiers, describing current or most recent episode

Severity/psychotic/remission specifiers for major depressive episode

Severity/psychotic/remission specifiers for manic episode

Severity/psychotic/remission specifiers for mixed episode

Chronic specifier for a major depressive episode

Catatonic features specifier

Melancholic features specifier

Atypical features specifier

Postpartum onset specifier

Specifiers, describing course of recurrent episodes

Longitudinal course specifiers (with and without full interepisode recovery)

Seasonal pattern specifier

Rapid cycling specifier

Major depressive episode and major depressive disorder sound similar but are conceptually distinct. Major depressive episode denotes a period of at least 2 weeks marked by the presence of at least 5 of 7 specific symptoms, 1 of which must be either depressed mood or markedly diminished interest or pleasure. The term major depressive episode is not applied when the patient also meets the following criteria: (1) if the symptoms do not cause clinically significant distress or impairment for a manic episode, (2) if the symptoms are directly attributable to substance or medical condition, or (3) if the symptoms are because of bereavement (this last item is controversial). Many patients with a major depressive episode qualify for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, either single episode or recurrent. But a diagnosis of major depressive disorder is only made if certain other disorders are ruled out (such as schizophrenia) and if the patient has never had a manic episode. The DSM-IV-TR recommends the diagnosis of major depressive disorder only for those patients who do not have a bipolar disorder, or what used to be called manic-depressive disorder. If there is a past history of a manic episode, the diagnosis is bipolar I disorder. If only milder manic-range episodes, called hypomanic episodes, have been present, the diagnosis is bipolar II disorder. Bipolar disorders are less common than major depressive disorders. However, the inadvertent prescription of an antidepressant to patients with bipolar disorder can destabilize them and is a major iatrogenic risk associated with primary care physicians (PCPs) or urologists prescribing antidepressants. Bottom line, the clinician initially consulted should screen every patient with ED for major mood disorders. However, once screened and identified as potentially having a major mental disorder, the patient should be referred to a mental health professional (MHP), typically a psychiatrist for sophisticated diagnostic typing.

Depression, like ED, occurs more frequently in the medically ill. Rates of depression have been shown to increase with the increasing number and acuity of medical illnesses. For example, studies have found increased risk for major depression in patients with cardiovascular, endocrine, and inflammatory diseases at rates triple those of usual populations. Furthermore, depression is an independent risk factor for those diseases including greater risk of mortality after acute myocardial infarction.

Etiology: the bidirectional relationship between ED and depression

Correlations have been noted between depression and aspects of sexual function, including erectile function. Experiencing ED can of course be a cause or precipitator of a depression of greater magnitude. History taking is critical in determining whether depression is a consequence of the ED, or if ED is more determined by the depression and its treatments. Most cases of reactive depression resolve upon improvement of sexual function. In fact, for a select subpopulation of depressed men with ED, the use of phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors alone is adequate in resolving the depression.

Shabsigh and colleagues concluded that ED is associated with a high incidence of depressive symptoms independent of age, marital status, or comorbid conditions and that depressed patients with ED had a lower libido than patients who did not exhibit depression. These patients were also less likely than others to continue a treatment of ED. There is a link between depression and nocturnal penile tumescence (NPT). In an early case report, 2 severely depressed men with ED were noted to have virtually absent NPT, which normalized, with successful antidepressant treatment. A subsequent series measuring NPT found that, compared with nondepressed controls, men with depression showed decreased total sleep tumescence time and were more likely to have absence of rigid nocturnal erections.

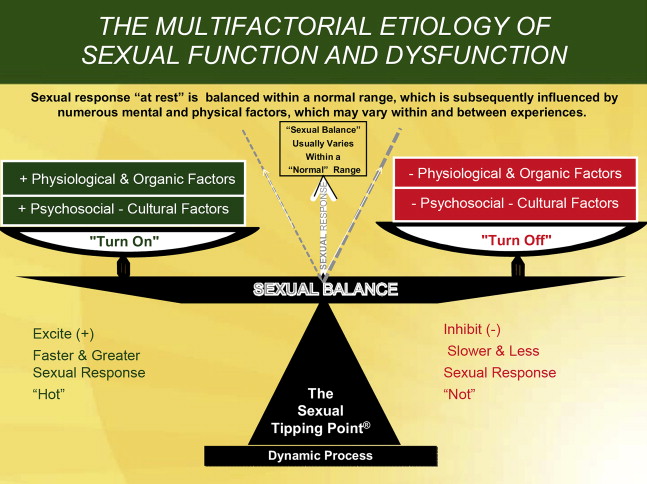

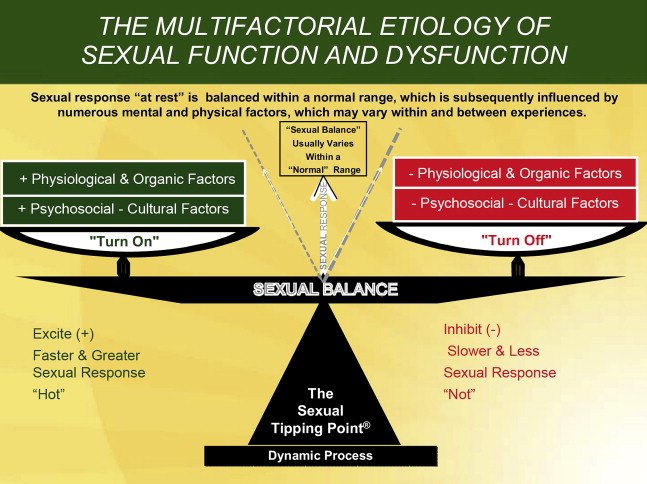

The relationship between depression and ED is complex, and it can be difficult to distinguish which occurred first. Depression can be a major consequence of ED, yet inversely, depression and its treatments can both cause ED. Finally, although factors such as stress, alcohol, or hypogonadism can contribute to both depression and ED, it is quite plausible that a mechanism, as yet unknown, may lead to both ED and depression. Such an interaction can be understood in terms of several theoretical models that discuss how the mind and body both inhibit and excite sexual response, creating a unique dynamic balance.

Bancroft and Kaplan both described a delicate balance between central excitatory and inhibiting mechanisms, adding greater understanding of the role of anxiety and other psychogenic factors in ED. Subsequently, Perelman postulated The Sexual Tipping Point (STP) model, which expanded this dual control concept to include all aspects of sexual functioning and dysfunction. This useful heuristic model defined a characteristic threshold for the expression of a sexual response for any individual, which could vary dynamically within and between individuals and for any given sexual experience ( Fig. 1 ).

Although the exact nature of a biological predisposition is not known, it is reasonable to conclude that the threshold for onset of either erectile difficulty and/or depression may have a distribution curve like that of numerous other human variables, such as height. The specific threshold for any specific function is determined by multiple factors for any given moment or circumstance. One or another factor dominates, whereas the others recede in importance. Determining whether the exact physiologic mechanisms of such thresholds are central, peripheral, and/or some combination requires further research.

These biological set points for erectile latency and depression (as well as other comorbid disease thresholds) are affected by multiple organic and psychogenic factors in varying combinations over the course of a man’s life cycle. However, this pattern of biological susceptibility presumably interacts with a variety of circumstances and intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics, in addition to environmental and medical risk factors, resulting in manifest disorders. These concepts can help us understand both ED and depression, as well as lead to identification of both the types and severity of factors that underlie both disorders. Clinicians can understand both ED and depression by recognizing how these predisposing, precipitating, and maintaining psychosocial-cultural causes, organic causes, and risk factors are all interrelated. Yet, ED and depression can both be elicited by a purely organic factor at one time and a completely cultural/environmental in another instance. There is a subsequent typical cascade of secondary physiologic and psychosocial consequences that exacerbate the end points of the depressed mood, energy level, appetites, and sexual function. To further explore the cause of comorbid ED and depression, the next section focuses on some of the key factors. Although there is a spurious risk of oversimplifying a multidimensional nuanced cause, clarity of presentation requires such an organizational structure.

Depression, ED, and the Metabolic Syndrome

Clinicians have often observed that men with depression and hypogonadism often report a similar set of symptoms: fatigue, lack of sexual energy, depressed mood, and a sense of diminished psychological well-being. It may be difficult to determine the correct diagnosis, and the 2 conditions may also coexist in the same patient. Some evidence suggests that testosterone supplementation may benefit at least some men who are depressed, particularly those with low serum testosterone levels. Studies by Kupelian and colleagues and Pope and colleagues have successfully documented the potential role for testosterone augmentation therapy in depressed men with testosterone levels in the low-normal range.

The multiple biological mechanisms that can be involved causing ED (including type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia) characterize the metabolic syndrome. Recent advances in understanding the systemic effects of depression have suggested that depression can exacerbate, can contribute to, and is highly associated with this syndrome. In particular, older men may develop a major depressive episode along with ED, sometimes in association this metabolic syndrome. There are of course other endocrine concerns, which are discussed by Guay elsewhere in this issue.

Psychogenic

Psychological issues often involve personality disorders, loss, and stresses of life, such as financial pressures. Relationship problems and other psychosocial events/stresses frequently contribute to, result from, or sometimes cause both ED and depression. The relevance of psychogenic factors should especially be considered for men with acquired and/or situational ED. Alterations in perceptual and attention processes (negative cognitions) can directly result in both mood and erectile variations. In addition, performance anxiety may lead a man to engage in behaviors such as “spectatoring” during intercourse, which focuses attention away from arousing stimulus and instead on negative cognitions and consequently has a dampening effect on both erectile capacity and mood. Thought affects the body biologically, not just psychologically. “In the anxious individual, there can be over-activity of the sympathetic system leading to increased smooth muscle tone. Alternatively, signals from the brain of an individual with a psychogenic issue can override the erotogenic parasympathetic output from the sacral spinal cord.”

Treatments for Depression Resulting in ED

Drugs, whether prescribed or taken recreationally, are perhaps one of the most common causes of diminished sexual capacity. Commonly prescribed medications are known to affect erectile function. For a detailed discussion of pharmacology and sex, the reader is recommended to the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) Consultation texts on Sexual Medicine. Some of the most important groups of pharmacologic agents to consider are antidepressants, centrally acting antihypertensive drugs, central nervous system depressants, β-adrenoceptor antagonists, and any drug that has an anticholinergic action. It is ironic that antidepressants seem to be independently associated with male sexual disorders. It is difficult to separate the ED risk of antidepressants from ED associated with depression. In individual cases, a thorough baseline history of erectile function before antidepressant treatment usually helps in clarifying the cause of the ED.

The chronic nature of depression in many cases and the subsequent need for long-term administration of antidepressants has enriched our knowledge of the sexual side effects of these medications. Estimates of the percentage of patients affected in later studies are likely to be more accurate than the estimates in earlier studies that relied on spontaneous reporting, which is known to underestimate the true incidence. Side effects of antidepressant treatment on sexual function are a serious issue for patients and their partners. Semipermanent interruption of sexual function by these medications is a significant barrier to medication adherence.

Clinicians should be aware that the sexual side effects of antidepressant medications are quite variable. The mechanisms by which selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants impair sexual function is the focus of ongoing research, but it is presumed to be caused by differential action of the relevant neurotransmitters. For instance, serotonin is known to act as an inhibitor of sexual response, so that drugs such as SSRIs, which increase serotonin levels, probably inhibit sexual function. In addition, there is speculation that some SSRI antidepressants by centrally inhibiting nitric oxide synthetase may be involved in SSRI-related ED. However, the primary sexual side effect associated with SSRIs is their effect on ejaculation and orgasm, with libido being second. Although SSRIs may also have a secondary effect on the erectile capacity, ED is the least common of the sexual negative effects with approximately 10% occurrence rate; however, in some cases, it has been reported to be irreversible.

Etiology: the bidirectional relationship between ED and depression

Correlations have been noted between depression and aspects of sexual function, including erectile function. Experiencing ED can of course be a cause or precipitator of a depression of greater magnitude. History taking is critical in determining whether depression is a consequence of the ED, or if ED is more determined by the depression and its treatments. Most cases of reactive depression resolve upon improvement of sexual function. In fact, for a select subpopulation of depressed men with ED, the use of phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors alone is adequate in resolving the depression.

Shabsigh and colleagues concluded that ED is associated with a high incidence of depressive symptoms independent of age, marital status, or comorbid conditions and that depressed patients with ED had a lower libido than patients who did not exhibit depression. These patients were also less likely than others to continue a treatment of ED. There is a link between depression and nocturnal penile tumescence (NPT). In an early case report, 2 severely depressed men with ED were noted to have virtually absent NPT, which normalized, with successful antidepressant treatment. A subsequent series measuring NPT found that, compared with nondepressed controls, men with depression showed decreased total sleep tumescence time and were more likely to have absence of rigid nocturnal erections.

The relationship between depression and ED is complex, and it can be difficult to distinguish which occurred first. Depression can be a major consequence of ED, yet inversely, depression and its treatments can both cause ED. Finally, although factors such as stress, alcohol, or hypogonadism can contribute to both depression and ED, it is quite plausible that a mechanism, as yet unknown, may lead to both ED and depression. Such an interaction can be understood in terms of several theoretical models that discuss how the mind and body both inhibit and excite sexual response, creating a unique dynamic balance.

Bancroft and Kaplan both described a delicate balance between central excitatory and inhibiting mechanisms, adding greater understanding of the role of anxiety and other psychogenic factors in ED. Subsequently, Perelman postulated The Sexual Tipping Point (STP) model, which expanded this dual control concept to include all aspects of sexual functioning and dysfunction. This useful heuristic model defined a characteristic threshold for the expression of a sexual response for any individual, which could vary dynamically within and between individuals and for any given sexual experience ( Fig. 1 ).

Although the exact nature of a biological predisposition is not known, it is reasonable to conclude that the threshold for onset of either erectile difficulty and/or depression may have a distribution curve like that of numerous other human variables, such as height. The specific threshold for any specific function is determined by multiple factors for any given moment or circumstance. One or another factor dominates, whereas the others recede in importance. Determining whether the exact physiologic mechanisms of such thresholds are central, peripheral, and/or some combination requires further research.

These biological set points for erectile latency and depression (as well as other comorbid disease thresholds) are affected by multiple organic and psychogenic factors in varying combinations over the course of a man’s life cycle. However, this pattern of biological susceptibility presumably interacts with a variety of circumstances and intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics, in addition to environmental and medical risk factors, resulting in manifest disorders. These concepts can help us understand both ED and depression, as well as lead to identification of both the types and severity of factors that underlie both disorders. Clinicians can understand both ED and depression by recognizing how these predisposing, precipitating, and maintaining psychosocial-cultural causes, organic causes, and risk factors are all interrelated. Yet, ED and depression can both be elicited by a purely organic factor at one time and a completely cultural/environmental in another instance. There is a subsequent typical cascade of secondary physiologic and psychosocial consequences that exacerbate the end points of the depressed mood, energy level, appetites, and sexual function. To further explore the cause of comorbid ED and depression, the next section focuses on some of the key factors. Although there is a spurious risk of oversimplifying a multidimensional nuanced cause, clarity of presentation requires such an organizational structure.

Depression, ED, and the Metabolic Syndrome

Clinicians have often observed that men with depression and hypogonadism often report a similar set of symptoms: fatigue, lack of sexual energy, depressed mood, and a sense of diminished psychological well-being. It may be difficult to determine the correct diagnosis, and the 2 conditions may also coexist in the same patient. Some evidence suggests that testosterone supplementation may benefit at least some men who are depressed, particularly those with low serum testosterone levels. Studies by Kupelian and colleagues and Pope and colleagues have successfully documented the potential role for testosterone augmentation therapy in depressed men with testosterone levels in the low-normal range.

The multiple biological mechanisms that can be involved causing ED (including type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia) characterize the metabolic syndrome. Recent advances in understanding the systemic effects of depression have suggested that depression can exacerbate, can contribute to, and is highly associated with this syndrome. In particular, older men may develop a major depressive episode along with ED, sometimes in association this metabolic syndrome. There are of course other endocrine concerns, which are discussed by Guay elsewhere in this issue.

Psychogenic

Psychological issues often involve personality disorders, loss, and stresses of life, such as financial pressures. Relationship problems and other psychosocial events/stresses frequently contribute to, result from, or sometimes cause both ED and depression. The relevance of psychogenic factors should especially be considered for men with acquired and/or situational ED. Alterations in perceptual and attention processes (negative cognitions) can directly result in both mood and erectile variations. In addition, performance anxiety may lead a man to engage in behaviors such as “spectatoring” during intercourse, which focuses attention away from arousing stimulus and instead on negative cognitions and consequently has a dampening effect on both erectile capacity and mood. Thought affects the body biologically, not just psychologically. “In the anxious individual, there can be over-activity of the sympathetic system leading to increased smooth muscle tone. Alternatively, signals from the brain of an individual with a psychogenic issue can override the erotogenic parasympathetic output from the sacral spinal cord.”

Treatments for Depression Resulting in ED

Drugs, whether prescribed or taken recreationally, are perhaps one of the most common causes of diminished sexual capacity. Commonly prescribed medications are known to affect erectile function. For a detailed discussion of pharmacology and sex, the reader is recommended to the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) Consultation texts on Sexual Medicine. Some of the most important groups of pharmacologic agents to consider are antidepressants, centrally acting antihypertensive drugs, central nervous system depressants, β-adrenoceptor antagonists, and any drug that has an anticholinergic action. It is ironic that antidepressants seem to be independently associated with male sexual disorders. It is difficult to separate the ED risk of antidepressants from ED associated with depression. In individual cases, a thorough baseline history of erectile function before antidepressant treatment usually helps in clarifying the cause of the ED.

The chronic nature of depression in many cases and the subsequent need for long-term administration of antidepressants has enriched our knowledge of the sexual side effects of these medications. Estimates of the percentage of patients affected in later studies are likely to be more accurate than the estimates in earlier studies that relied on spontaneous reporting, which is known to underestimate the true incidence. Side effects of antidepressant treatment on sexual function are a serious issue for patients and their partners. Semipermanent interruption of sexual function by these medications is a significant barrier to medication adherence.

Clinicians should be aware that the sexual side effects of antidepressant medications are quite variable. The mechanisms by which selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants impair sexual function is the focus of ongoing research, but it is presumed to be caused by differential action of the relevant neurotransmitters. For instance, serotonin is known to act as an inhibitor of sexual response, so that drugs such as SSRIs, which increase serotonin levels, probably inhibit sexual function. In addition, there is speculation that some SSRI antidepressants by centrally inhibiting nitric oxide synthetase may be involved in SSRI-related ED. However, the primary sexual side effect associated with SSRIs is their effect on ejaculation and orgasm, with libido being second. Although SSRIs may also have a secondary effect on the erectile capacity, ED is the least common of the sexual negative effects with approximately 10% occurrence rate; however, in some cases, it has been reported to be irreversible.

Diagnosis and screening

The history obtained by PCPs and urologists is frequently limited to an end-organ focus and fails to reveal significant psychosocial barriers to successful restoration of sexual health. These obstacles or resistances represent an important cause of nonresponse and treatment discontinuation. These barriers manifest themselves in varying levels of complexity, which individually and/or collectively must be understood and managed for the pharmaceutical treatment to be optimized. Only recently have clinicians begun incorporating sex therapy concepts and have recognized that resistance to lovemaking is often emotional. Most of these barriers to success can be managed as part of the treatment, yet too few clinicians are trained to do so.

Screening

Although the patient is initially evaluated for ED, there is a secondary goal of evaluating the management algorithm for any other significant disease or disorder. When depression is suspected, the physician must explore the mental status of the patient with an emphasis on assessing this mood disorder. This assessment can be done by the examining clinician alone or by working within a multidisciplinary team. The primary goal of the evaluation visit is to obtain the necessary information to assess the nature of the ED and to begin developing a treatment plan. Guidance for brief screening or a “sex status” examination of the patient with ED has been well described elsewhere. Therefore, it is only briefly summarized in the following section, whereas specific screening techniques and questionnaires for depression are highlighted.

The Sexual Status Examination or Sex Status Exam

The sex status focuses on finding potential physical and specific psychosocial factors relating to the disorder. It is also important to ascertain why the patient is seeking assistance at that particular time. The clinician should first obtain a clear and detailed description of the patient’s sexual symptoms, as well as information about the onset and progression of symptoms. The details of the physical and emotional circumstances surrounding the onset of a difficulty are important for the assessment of both physical and psychological causes. The ideal history is an integrated, fluid assessment, in which the patient’s response is continuously reevaluated during follow-up. The successful treatment of ED requires answers to 3 key questions regarding diagnosis, cause, and treatment: (1) Does the patient really have a sexual disorder and what is the differential diagnosis? (2) What are the underlying organic and/or psychosocial factors? (3) Should the patient be treated or not? Do the underlying organic and psychosocial factors require priority treatment, or can the treatment of these factors be bypassed or concurrent? These decisions are dynamic and should be consistently reevaluated as the treatment proceeds.

The methodology used to answer these questions is a focused history. Obviously, the clinician must determine whether the patient has an illness or is taking a drug that could be causing the symptom. However, this article presumes that the necessary assessment steps and procedures, including physical examination, as well as laboratory tests have been conducted in a manner consistent with the parameters recommended by Broderick elsewhere in this issue. By the end of the evaluation visit, the physician should have already ascertained or identified the necessary next steps to determine the extent to which there is an endocrine (eg, diabetes, androgens), neurogenic, vascular, psychogenic, and/or drug-related basis to the patient’s ED. However, the clinician should not arbitrarily separate the psychosocial/sexual history from the medical history. An integrated medical and sexual history yields a significant amount of information regarding all aspects of a man’s sexual health and relationships.

It is not necessary to do an exhaustive sexual and family history for most evaluations. The investigation of these issues should be selective so that the interview does not become unnecessarily lengthy. The clinician should briefly screen all patients for obvious psychopathology that would significantly interfere with the initiation of treatment of ED. Yet, the clinician will also want to know whether psychiatric symptoms, if present, are the cause and/or the consequence of the sexual disorder. If the patient is depressed, the severity of his depression must be clarified. Any patient who experiences major depression should be queried about suicide risk.

For all men, clinicians should assess the living and marital/dating status. Contextual factors, including difficulties with the current interpersonal relationship and whether the partner has an SD, should be clarified. The clinician may grasp the couple’s interactions from the first interview’s sex status. Numerous partner-related nonsexual issues may adversely affect the outcome. The degree of acrimony should be monitored when the patient describes his complaints, including is the anger, resentment, hurt, or sadness a maintaining or precipitating factor, or are the emotions more mild manifestations of the frustrations of daily life. Severe marital strife will inevitably require a referral to an MHP, albeit it may not be successfully accepted. The single patient with ED must be assessed in the same manner as if the patient was in a relationship. The patient’s sexual symptom may or may not relate to difficulties in his relationships. Needless to say, sexual orientation issues, for both single and coupled men, require the same, if not even greater sensitivity on the clinician’s part.

Questionnaires

Chochinov and colleagues were able to demonstrate that the mere asking of a single question, “Are you depressed?” was at least as effective as questionnaires in detecting depression. Yet, some clinicians may choose to use current or future instruments to facilitate the history-taking process. Two such instruments are briefly described below, but such instruments must be incorporated in a manner that does not interfere with rapport. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) rating scale, developed specifically for the medical office practice, is a convenient way to screen medical office patients for major depressive episode. It can be completed either by the patient himself or by the practitioner interviewing the patient. The PHQ-9 scale is easily scored to provide a measure of depression severity, and includes an item asking specifically about suicidal thoughts. In addition, the Depression in the Medically Ill Scale is a 10-item questionnaire that is 85% effective in detecting depression without the necessity of a psychiatric evaluation, which can be used by busy clinicians as a screening device.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree