Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated condition whereby infiltration of eosinophils into the esophageal mucosa leads to symptoms of esophageal dysfunction. EoE is encountered in a substantial proportion of patients undergoing diagnostic upper endoscopy. This review discusses the clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of EoE and presents the most recent guidelines for its diagnosis. Selected diagnostic dilemmas are described, including distinguishing EoE from gastroesophageal reflux disease and addressing the newly recognized clinical entity of proton-pump inhibitor–responsive esophageal eosinophilia. Also highlighted is evidence to support both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments, including topical corticosteroids, dietary elimination therapy, and endoscopic dilation.

Key points

- •

Over the past 10 years, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has become a major cause of gastrointestinal symptoms, including dysphagia and food impaction in adolescents and adults, and feeding intolerance, failure to thrive, regurgitation, heartburn, and vomiting in children.

- •

EoE is a clinicopathologic condition, so the entire clinical and histologic picture must be considered in making a diagnosis; no single feature is diagnostic on its own.

- •

EoE is now diagnosed based on consensus guidelines requiring symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, at least 15 eosinophils per high-power microscopy field on esophageal biopsy, and eosinophilia limited to the esophagus with other causes of esophageal eosinophilia (including proton-pump inhibitor–responsive esophageal eosinophilia) excluded.

- •

Effective first-line treatment strategies include topical steroids, such as swallowed fluticasone or budesonide, or dietary therapy with an elemental formula, a 6-food elimination diet, or a targeted elimination diet.

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is currently defined as a chronic immune-mediated condition whereby infiltration of eosinophils into the esophageal mucosa leads to symptoms of esophageal dysfunction. Although the first case was described in the late 1970s, the disease as it is now recognized was reported in children and adults in the early 1990s. EoE was initially thought to be rare, but data from multiple centers now show that the incidence and prevalence are increasing rapidly and have outpaced the increased recognition of the disease. In fact, over the past 10 years EoE has become an important and frequent cause of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in both children and adults. More than 6% of patients undergoing upper endoscopy for any reason, and more than 15% having the procedure for an indication of dysphagia, will be diagnosed with EoE. The prevalence of EoE has been estimated to range between 43 to 52 per 100,000 in the general population, a level that is beginning to approach the population prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease.

The increasing recognition and evolving epidemiology of EoE has led to an explosion of research interest. Although many questions related to EoE remain unanswered, there has been substantial progress toward understanding the pathogenesis and genetic basis of the disease, the clinical presentation, and effective treatment strategies. This review discusses clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of EoE, presents the most recent guidelines for the diagnosis of EoE and selected diagnostic dilemmas, and highlights evidence to support both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment.

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is currently defined as a chronic immune-mediated condition whereby infiltration of eosinophils into the esophageal mucosa leads to symptoms of esophageal dysfunction. Although the first case was described in the late 1970s, the disease as it is now recognized was reported in children and adults in the early 1990s. EoE was initially thought to be rare, but data from multiple centers now show that the incidence and prevalence are increasing rapidly and have outpaced the increased recognition of the disease. In fact, over the past 10 years EoE has become an important and frequent cause of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in both children and adults. More than 6% of patients undergoing upper endoscopy for any reason, and more than 15% having the procedure for an indication of dysphagia, will be diagnosed with EoE. The prevalence of EoE has been estimated to range between 43 to 52 per 100,000 in the general population, a level that is beginning to approach the population prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease.

The increasing recognition and evolving epidemiology of EoE has led to an explosion of research interest. Although many questions related to EoE remain unanswered, there has been substantial progress toward understanding the pathogenesis and genetic basis of the disease, the clinical presentation, and effective treatment strategies. This review discusses clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of EoE, presents the most recent guidelines for the diagnosis of EoE and selected diagnostic dilemmas, and highlights evidence to support both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment.

Patient history

EoE has been described throughout the world including North America, Europe, South America, Australia, and Asia, but the prevalence appears to be highest in the United States and Western Europe in comparison with Japan and China. It also occurs in patients of all ages, but is more frequent in children and adults younger than 40 years. For reasons that are not understood, EoE is seen 3 to 4 times more frequently in males than in females, and is also more common in whites. However, as centers accrue more experience and report data from larger populations of subjects from more diverse areas, racial minorities have also been found to have EoE.

The clinical presentation of EoE varies by patient age. In infants and toddlers symptoms are nonspecific, and can include failure to thrive, fussiness, poor growth, feeding intolerance or food aversion, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and regurgitation. By contrast, dysphagia is the most characteristic symptom in adolescents and adults, and in some studies this symptom is nearly universal. For patients who present to an emergency department with a food impaction, EoE is the cause at least 50% of the time. Of importance is that patients can minimize symptoms of dysphagia by avoiding solid foods, lubricating foods, drinking copious liquids during meals, and chewing carefully, so asking about these dietary modifications is necessary. Heartburn can affect patients with EoE of any age, and in 1% to 8% of those with proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) refractory reflux symptoms, EoE is the cause. Because of the many potential symptoms and because no single symptom is specific for EoE, there is often a delay in making the diagnosis.

EoE is also strongly associated with atopic diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, atopic dermatitis, and food allergies. This relationship was first reported in children, up to 80% of whom can have atopy, and helped to support the allergic etiology of EoE. Although fewer adults with EoE have atopy, it is still a prominent feature in this population. There have been several reports of seasonal variation in the diagnosis of EoE as well as variation based on climate zone.

Endoscopic features

Upper endoscopy is required for evaluation of clinical symptoms of EoE, assessment for other possible causes, and performance of esophageal biopsies. Multiple characteristic endoscopic findings of EoE have been reported, but in up to 10% of cases the esophageal mucosa can appear normal, and biopsies are required or the diagnosis will be missed. These findings have a fair to good interobserver and intraobserver reliability, and efforts are under way to standardize reporting and scoring of endoscopic findings in EoE.

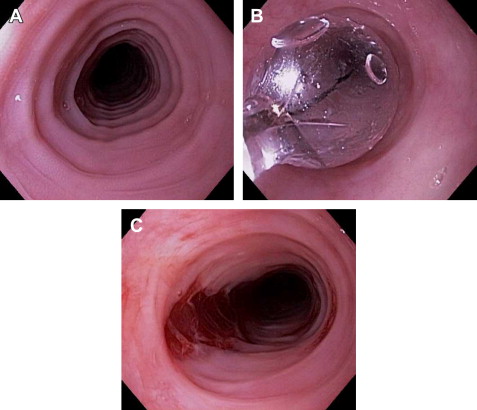

Typical endoscopic findings of EoE are presented in Fig. 1 , and include:

- •

Esophageal rings: these can be fixed (previously referred to as esophageal trachealization or corrugation) or transient (sometimes termed felinization).

- •

Narrow-caliber esophagus: this can be difficult to appreciate on visual inspection alone, but there can be resistance to the scope passage without seeing a clear stricture.

- •

Focal esophageal strictures.

- •

Linear furrows: grooves in the esophageal mucosa that run parallel to the axis of the esophagus.

- •

White plaques or exudates: punctate white spots on the esophageal mucosa that can be confused for esophageal candidiasis.

- •

Decreased vascularity: here the normal mucosal vascular pattern is lost and the esophagus appears pale, congested, or edematous.

- •

Crêpe-paper mucosa: a manifestation of mucosal fragility in EoE whereby the mucosa tears with passage of the endoscope, but a focal stricture or resistance is not appreciated.

These features can occur in isolation, but more commonly occur together. There are some data to suggest that younger children tend to have more inflammatory features such as linear furrows, white plaques, and decreased vasculature, whereas adults (particularly those with symptoms of long duration) tend to have more fibrotic features such as rings and strictures.

It is important to be aware that the endoscopic findings of EoE are not pathognomonic, and a recent meta-analysis found that the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of endoscopic findings in EoE were not high enough to be the basis for diagnostic decisions. This finding emphasizes the importance obtaining esophageal biopsies when EoE is suspected clinically. This tenet is reiterated in recent guidelines, which recognize that the eosinophilic infiltrate in EoE is patchy and that increasing numbers of biopsies increase diagnostic sensitivity. Therefore, it is recommended for the endoscopist to obtain 2 to 4 biopsies from the distal esophagus and an additional 2 to 4 samples from the proximal esophagus.

Histologic features

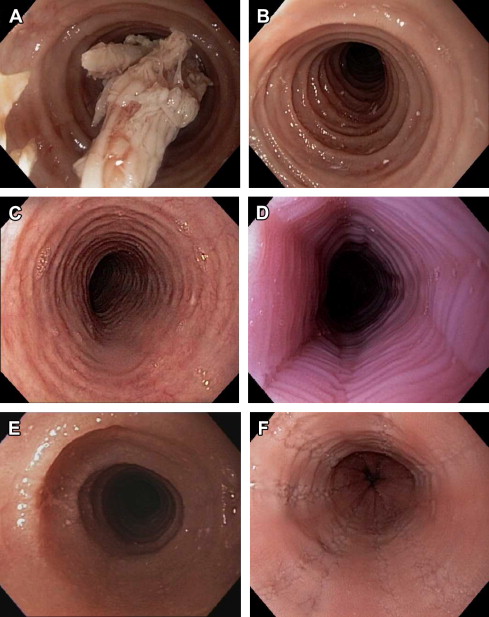

Infiltration of the esophageal mucosa with eosinophils is the histologic hallmark of EoE. At present, finding at least 15 eosinophils per high-power microscopy field (eos/hpf) is suggestive of EoE. However, as discussed in more detail later, the finding of esophageal eosinophilia on biopsy is not specific for EoE. When biopsy samples are examined, in addition to the eosinophil count, which by convention represents the peak value in the most highly inflamed area on the biopsy, other features are also present ( Fig. 2 ). Eosinophils are often found toward the apical aspect of the epithelium, and clusters of eosinophils can form eosinophilic microabscesses. Because eosinophils are activated in EoE, they degranulate, and the granule proteins can be seen extracellularly. There is also basal layer hypertrophy whereby the cells in the basal layer expand and the rete pegs elongate. Spongiosis, also termed dilated intracellular spaces, is frequently observed. Finally, if the biopsy sample is deep enough to contain lamina propria, fibrosis of this area can be noted.

Diagnostic criteria

Consensus Guidelines

Because of heterogeneity in disease definition and reporting of data pertaining to EoE, an initial set of diagnostic guidelines was proposed in 2007 and represented a major step forward for the field. These guidelines have been recently updated after taking into account advances in understanding and complexities related to diagnosis. In this most recent document, EoE is defined conceptually as a “chronic immune/antigen-mediated esophageal disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation.” Three specific criteria were required to diagnose EoE:

- •

Symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction

- •

A peak eosinophil count of at least 15 eos/hpf on esophageal biopsy, with few exceptions

- •

Eosinophilia limited to the esophagus with other causes of esophageal eosinophilia excluded

Taken together, the conceptual definition and the diagnostic criteria emphasize that EoE is a clinicopathologic condition. Specifically, the entire clinical and histologic picture must be considered to make a diagnosis, and no single feature is diagnostic on its own.

Diagnostic Dilemmas

Despite having a set of diagnostic guidelines, the ability to characterize patients clinically and endoscopically, well-defined histologic findings with a marker, and the eosinophil count, which is reliable and reproducible if approached systematically, diagnosis of EoE can still be challenging.

Just as symptoms of dysphagia and findings of esophageal rings on endoscopy are not specific for EoE, there is a differential diagnosis for esophageal eosinophilia on biopsy. Several conditions that have been reported to cause or be associated with esophageal eosinophilia, such as achalasia, infections (fungal, viral, parasitic), connective-tissue disease, graft-versus-host disease, Crohn disease, adrenal insufficiency, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and eosinophilic gastroenteritis, have their own distinct clinical presentations and can typically be diagnosed with a focused history and physical examination with limited supplemental evaluation. However, 2 conditions, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE), deserve special attention when attempting to diagnose EoE.

There is substantial overlap between GERD and EoE, including symptoms of heartburn, chest pain, and dysphagia, and biopsy findings of eosinophilia; even very high eosinophil counts, do not distinguish the two conditions. In the 2007 EoE diagnostic guidelines, exclusion of GERD, either with a high-dose PPI trial or with pH monitoring, was required before definitively diagnosing EoE. As more clinical experience was gained, it was clear that there were some patients who had coexisting EoE and GERD and that the relation between the two conditions was complicated.

In addition, there was the observation that some patients who appeared to have EoE would have a clinical and histologic response to PPI therapy. This finding was first reported in a case series by Ngo and colleagues, and since then several studies have reported that one-third or more of patients with esophageal eosinophilia have a response to PPIs. This phenomenon has been termed PPI-REE. It is not currently known whether this is a distinct clinical entity, a subtype of GERD, or a phenotype of EoE, but its role must currently be addressed in the diagnostic algorithm for EoE. Specifically, when esophageal eosinophilia is found on biopsy in a clinical setting where there is suspicion for EoE, a high-dose PPI trial (20–40 mg twice daily of any of the available agents for 8 weeks) is necessary. If a patient responds to this regimen, additional clinical evaluation can be performed to determine if GERD was the cause of the esophageal eosinophilia or if the patient has PPI-REE. If a patient has persistent symptoms of EoE and there are still at least 15 eos/hpf on esophageal biopsy, EoE can be diagnosed.

Because of these challenges and the somewhat rudimentary way in which EoE is diagnosed, there is active research aimed at identifying better ways to diagnose EoE. Some methods under investigation include clinical scoring systems, endoscopic imaging techniques, functional luminal assessment of the esophagus, biomarker measurements on esophageal biopsies, radiolabeling of esophageal biopsies, noninvasive assessment of esophageal cytokines, noninvasive serum biomarkers, and genetic testing. Although these techniques are promising, none have been validated or are ready to be used in clinical practice.

Treatment

There are now several evidence-based treatment options for EoE. Pharmacologic agents are commonly used, but nonpharmacologic approaches such as dietary elimination therapy and endoscopy dilation are also effective. Of note, there are currently no medications for EoE approved by the Food and Drug Administration, so all pharmacologic treatment options are off-label. The overall goal of treating patients with EoE is to improve symptoms and normalize the esophageal mucosa without adversely affecting quality of life, although specific end points have been difficult to define in clinical trials. Because EoE is chronic, when medications or dietary therapy are stopped, symptoms will recur for the majority of patients. For this reason, in patients with severe, frequent, or recurrent symptoms, or in patients who have had complications such as esophageal strictures, food impactions requiring emergency evaluation for endoscopy and bolus clearance, or esophageal perforations, long-term treatment may be required.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Corticosteroids

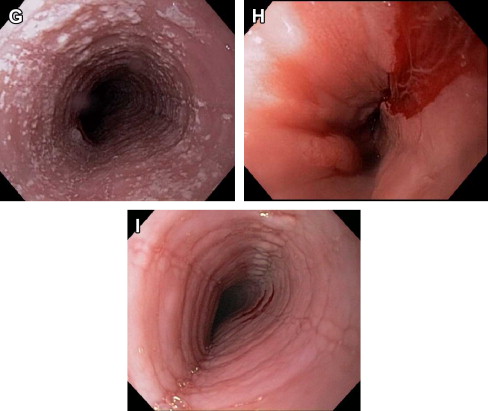

Corticosteroid medications are an effective and commonly used treatment for EoE ( Fig. 3 ). Initially systemic steroids were administered with good effect, but because of concerns about side effects, this class was not a viable option for long-term used. Instead, a topical method of administration of steroids was developed. Patients were instructed to use asthma medication preparations, either in a multidose inhaler (MDI) or aqueous-solution formulations, and instead of inhaling the medications they swallowed them to coat the esophagus. With this technique, several studies showed that agents such as fluticasone, budesonide, mometasone, beclomethasone, and ciclesonide all effectively decreased esophageal eosinophil counts and improved clinical symptoms. In addition, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Schaefer and colleagues that compared topical fluticasone with prednisone showed that the 2 agents were equivalent for improving symptoms and eosinophil counts.

The 2 most commonly used topical steroids are fluticasone and budesonide. The first placebo-controlled RCT in EoE was conducted in children by Konikoff and colleagues. Using fluticasone, they showed that 50% of the 21 subjects receiving fluticasone had complete histologic remission (defined as ≤1 eos/hpf) compared with 9% of the 15 subjects receiving placebo. Recently, a similar study was conducted in adults by Alexander and colleagues. Here, 62% of the 21 adults treated with fluticasone had a greater than 90% decrease in eosinophil counts, compared with 0% of the 15 subjects in the placebo arm. When used clinically the typical dose of fluticasone is 880 to 1760 μg/d, administered twice daily, with the final dose determined by the patient’s age or size.

Topical budesonide has also been studied. Here, the aqueous formulation of the medication is typically mixed with a sugar substitute such as sucralose, and the resultant slurry (which has been termed oral viscous budesonide, or OVB) is swallowed. In the first RCT in children, Dohil and colleagues reported that 87% of the 15 subjects who received OVB had a histologic response (≤6 eos/hpf), whereas none of the 9 patients in the placebo group had this response. The marked histologic response seen with budesonide was confirmed in a larger placebo-controlled dose-finding trial of 80 children, but in this study the symptoms significantly improved in both the active-therapy and placebo arms, making the results somewhat difficult to interpret and highlighting a trend that has been seen in some other recent trials. There have also been 2 RCTs of budesonide in adults. Straumann and colleagues compared a nebulized and then swallowed protocol for budesonide with placebo, and found that budesonide was highly effective for improving symptoms and decreasing eosinophil counts. The second study compared OVB with the nebulized/swallowed budesonide administration protocol, and showed that OVB was more effective. When used clinically, the typical dose of budesonide is 1 to 2 mg/d, mixed with 5 g of sucralose and administered twice daily, with the final dose determined by the patient’s age or size.

Topical steroids are generally considered safe and well tolerated. Adrenal suppression has not been reported with an initial course of treatment, but longer-term safety data are needed. The main adverse effect with topical steroids is local. The rate of candidal esophagitis ranges from 0% to 32% in prospective studies, although many of these cases were detected incidentally on follow-up endoscopy. There is also a case report of herpes esophagitis complicating topical steroid use.

Biological agents

There has been burgeoning interest in nonsteroid treatment modalities for eosinophilic esophagitis, and biological agents targeting key factors in the pathogenesis of EoE are intriguing options. To date, however, these are either still in the experimental phase or have not been shown to be effective.

Mepolizumab and reslizumab are monoclonal anti–interleukin-5 antibodies. A small series showed that mepolizumab had some efficacy for EoE, so these agents were subsequently studied in 3 RCTs, 1 in adults and 2 in children. There was a mild to moderate improvement in eosinophil counts, but the medications did not tend to improve symptoms in the active treatment arms compared with placebo, and primary end points of resolution of eosinophilia and symptoms were not met. These agents are not available clinically at present.

Infliximab, an anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody frequently used in inflammatory bowel disease, was examined in a small case series of steroid-refractory EoE patients, but did not improve symptoms or histology.

Omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody against immunoglobulin E and used for allergic asthma, was studied in a placebo-controlled RCT by Fang and colleagues in 30 adults with EoE. There was no difference in any of the outcomes between the groups, and this agent is not recommended for use in EoE.

Other agents

Given the strong association between EoE and allergic diseases, leukotriene antagonists have been studied, but the data are conflicting. In an initial report in adults by Atwood and colleagues, high doses of montelukast (20–40 mg/d) were effective, though associated with nausea and vomiting. Two additional studies, one in adults and one in children, were less encouraging, and this agent is not routinely used in EoE.

Mast-cell stabilizers such as cromolyn have also been examined, but were not effective. There are currently no data in EoE for ketotifen, an antihistamine with anti–mast cell properties.

Immunomodulators such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine have been studied in a single series of 3 patients with steroid-dependent EoE. Although the medication was effective for improving eosinophilic counts and maintaining symptom control, given the potential toxicity and paucity of data, this medication is not recommended for routine use in EoE.

Several investigations into novel agents to treat EoE are ongoing. For example, anti–interleukin-13 and anti–eotaxin-3 antibodies are under development, and pilot data were recently presented on a T-helper type 2 cell prostaglandin D2 receptor antagonist, which represents a potentially new medication class for EoE. With the increasing understanding of pathways involved in the pathogenesis of EoE, it is likely that a wide variety of therapeutic modalities will be studied over the coming years.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

There are 2 major strategies for nonpharmacologic treatment of EoE. The first is dietary elimination, whereby specific foods or groups of foods are removed from the diet to identify potential food allergens that trigger EoE. Similar to pharmacologic therapy, dietary restriction reduces esophageal eosinophilia. The second is endoscopic dilation whereby strictures, rings, or a narrow-caliber esophagus are stretched to relieve symptoms of dysphagia. This technique does not affect the underlying inflammation in the esophagus.

Dietary elimination

There are 3 approaches to dietary elimination for treatment of EoE. First is a completely allergen-free elemental formula, composed of only amino acids, medium-chain triglycerides, and simple carbohydrates. This treatment was initially used in one of the early reports of EoE in which 10 children responded within weeks of starting the formula. In a study of 51 children, Markowitz and colleagues found that 96% of subjects had near-complete resolution of esophageal eosinophilia and symptoms within 1 to 2 weeks, and other studies have reported similar results. Until recently, all of the data on elemental diets were in children, but a study by Peterson and colleagues confirms the short-term utility of this approach in adults as well, if they can tolerate the formulation. Although elemental diets are very effective for EoE treatment, they are unpalatable, expensive, sometimes require gastrostomy tubes for administration, and may not be feasible for many patients with EoE.

The second approach, the so-called 6-food elimination diet (SFED), addresses the difficulty with compliance found with the elemental diet. In the SFED, the 6 most highly allergenic food groups, dairy, egg, wheat, soy, nuts, and seafood, are removed from the diet. This approach compares favorably with the elemental diet in children, with three-quarters of subjects having resolution of esophageal eosinophilia and almost all having improvement in symptoms. Gonsalves and colleagues have now shown that the SFED is equally effective in adult patients as well.

Third is a targeted elimination diet whereby foods are removed based on reactivity on allergy testing. This method is less restrictive than either elemental or SFED diets, but the efficacy is also somewhat less, likely because allergy testing itself is not completely reliable for detecting food triggers. Several studies have explored this approach, and the overall response rate ranges between 50% and 75% in children and lower in adults, depending on the center and the methods of allergy testing used.

When selecting dietary modification as the treatment modality for a patient with EoE, it is important to have a multidisciplinary approach with collaboration between gastroenterologists, allergists, and nutritionists. This approach ensures not only that patients are having their nutrition requirements met, but also that they have enough information about food choices and potential sources of contamination to maximize the likelihood of success of the elimination diet.

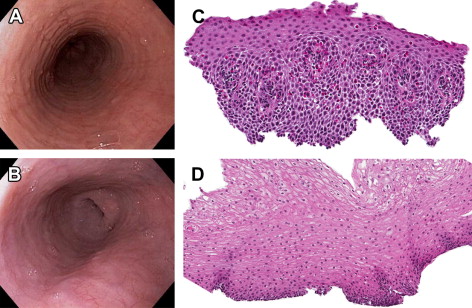

Endoscopic dilation

Endoscopic dilation is an effective way to treat dysphagia caused by strictures or narrow-caliber esophagus in patients with EoE ( Fig. 4 ). When the technique was first reported, however, there were high rates of complications such as esophageal perforation, mucosal rents, and hospitalization for postprocedural chest pain, and safety was a significant concern. As more experience with dilation in EoE patients has accumulated, however, the technique seems safer than originally believed, and a cautious approach has been endorsed. In several recently published studies and 2 systematic reviews the overall perforation rate is 0.3%, which is similar to the cited rate for upper endoscopy with dilation in patients who do not have EoE.