Endoscopy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Dahlia Awais

Peter Higgins

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopy has a key role in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Although there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of IBD, endoscopy provides essential information in establishing a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease (CD). Endoscopy is also critical in the follow-up of patients with IBD in the form of dysplasia surveillance, the assessment of medically refractory IBD, and in the evaluation of anorectal disease, IBD-related biliary disease (primary sclerosing cholangitis [PSC]), and the pouch after ileoanal anastomosis. It can be used for the dilation of strictures and for the assessment of mucosal healing in response to therapy. Newer technologies, including capsule endoscopy and balloon enteroscopy, have provided additional diagnostic and therapeutic options for the evaluation and treatment of small bowel CD.

DIAGNOSIS

Several colitides, including infectious colitis, ischemic colitis, radiation colitis, druginduced colitis, and diverticular colitis, can present with symptoms identical to IBD, including bloody diarrhea, urgency, and tenesmus. When stool studies are negative for infectious etiologies (including Clostridium difficile and Escherichia coli 0157:H7), endoscopic evaluation for diagnosis is indicated. Although endoscopic findings alone are not specific, characteristic patterns and mucosal biopsies are essential in distinguishing IBD from other colitides and in differentiating UC from CD (1).

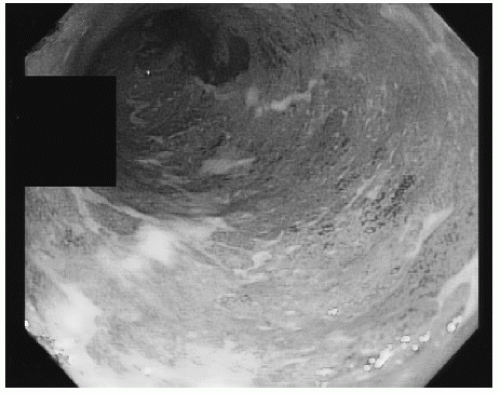

Endoscopically, UC is suggested by inflammatory changes that begin at the anal verge and extend proximally in a continuous and circumferential fashion, and are generally limited to the colon. Findings are nonspecific and may include erythema, loss of vascular pattern, edema, friability, and a granular-appearing mucosa (Fig. 2.1). Similar findings may be seen with ischemic or infectious colitis, and a diagnosis cannot be made based on endoscopic appearance alone. UC can include distal disease with isolated periappendiceal inflammation (a cecal patch). Additionally, while the terminal ileum is typically not involved in UC, up to 10% of patients with pan-UC will have inflammation of the distal terminal ileum, termed “backwash ileitis” (2).

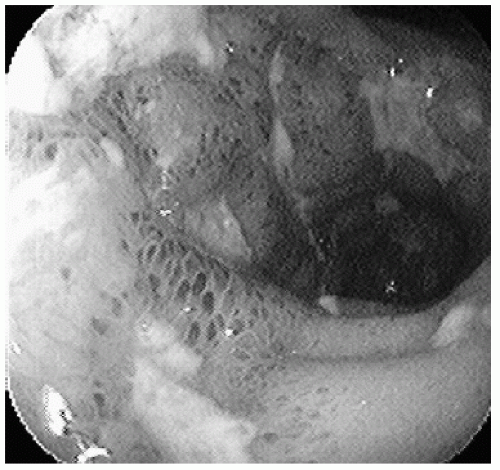

In contrast, the distinguishing endoscopic features of CD include involvement anywhere in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, “skip” lesions (patchy inflammation adjacent to normal mucosa), rectal sparing, aphthous ulcerations, and a cobblestone appearance of the mucosa due to the presence of deep linear ulcers (Fig. 2.2) (3). Although involvement of the terminal ileum is highly suggestive of Crohn’s, ileal ulcers may also be seen with inflammatory drugs use and in the setting of infection with Yersinia or tuberculosis. It should be noted that treatment can alter the endoscopic appearance of IBD, at times making a distinction between CD and UC difficult, particularly in the setting of mucosal healing in the rectum, which can be mistaken for “rectal sparing.” While 0.5% to 13% of patients with Crohn’s may have involvement of the upper GI tract, they generally have ileocolonic involvement as well (4); therefore, while esophagogastroduodenoscopy to evaluate for upper GI

involvement is not routinely indicated for all patients suspected of having Crohn’s, it may be useful in the evaluation of patients with indeterminate colitis (1).

involvement is not routinely indicated for all patients suspected of having Crohn’s, it may be useful in the evaluation of patients with indeterminate colitis (1).

FIGURE 2.1 Ulcerative colitis. Continuous circumferential inflammation characterized by loss of vascular pattern and a granular-appearing mucosa. |

FIGURE 2.2 Crohn’s disease. Cobblestone-appearing mucosa with submucosal hemorrhages and deep linear ulcers. |

Because endoscopic features are not diagnostic, mucosal biopsies are useful in distinguishing between an acute self-limited colitis and IBD (5). Multiple biopsies should be taken from different colonic segments of inflamed and normal-appearing mucosa, and they should be placed in separate bottles reflecting location and whether the mucosa appears normal or inflamed (1). Features of chronicity that

suggest IBD include villous mucosal architecture, Paneth cell metaplasia, crypt distortion, and atrophy, as well as mixed lamina propria inflammation with eosinophils and basal plasmacytosis (6,7). CD may be suggested by noncaseating granulomas; however, granulomas may be seen in other conditions, their absence is common, and this absence does not exclude the diagnosis of CD (5,6). UC cannot definitively be distinguished from CD on the basis of histology alone, although the finding of an epithelioid granuloma not associated with a ruptured cyst is characteristic of Crohn’s (8). Although endoscopy plays an essential role, IBD diagnosis is ultimately based on a combination of clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and radiographic findings.

suggest IBD include villous mucosal architecture, Paneth cell metaplasia, crypt distortion, and atrophy, as well as mixed lamina propria inflammation with eosinophils and basal plasmacytosis (6,7). CD may be suggested by noncaseating granulomas; however, granulomas may be seen in other conditions, their absence is common, and this absence does not exclude the diagnosis of CD (5,6). UC cannot definitively be distinguished from CD on the basis of histology alone, although the finding of an epithelioid granuloma not associated with a ruptured cyst is characteristic of Crohn’s (8). Although endoscopy plays an essential role, IBD diagnosis is ultimately based on a combination of clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and radiographic findings.

SURVEILLANCE

Patients with proctitis or proctosigmoiditis are not at increased colorectal cancer (CRC) risk compared with the general population; however, patients with UC extending beyond the distal sigmoid and rectum, and patients with Crohn’s colitis involving more than one third of the colon, are at increased risk (9,10). Guidelines recommend initiation of surveillance 8 to 10 years after the onset of symptoms in this high-risk group (1,11,12). Patients known to have PSC and IBD have additional risk (13), and surveillance should begin once PSC is diagnosed (1,11,12). Although the literature does not provide clear evidence for a survival benefit, there is indirect evidence that endoscopic surveillance may decrease CRC-related mortality and may be cost-effective (14).

In patients with IBD, dysplasia and CRC may arise in flat mucosa and may be difficult to visualize endoscopically. For surveillance, random biopsies are therefore obtained for microscopic detection of neoplasia. Current guidelines recommend surveillance colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years with four-quadrant biopsies taken every 10 cm from the cecum to the rectum, with additional biopsies of raised or suspicious lesions and adjacent mucosa placed in separate jars (1,11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree