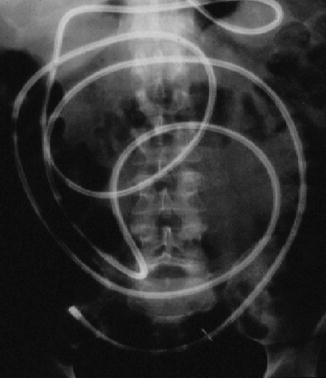

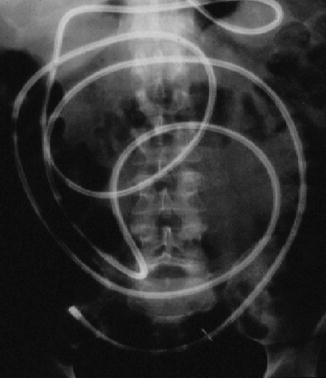

Fig. 3.1

X-ray of push enteroscopy using a 2 m long instrument

It was 1982 when the first report demonstrated the use of enteroscopy in the diagnosis of a small bowel tumor. Shinya reported on the initial use of both sonde and push enteroscopy and described finding a duodenal adenocarcinoma and a jejunal hemangiolymphangioma [17]. The role of enteroscopy in the diagnosis of small bowel tumors has developed since that time. Often, small bowel tumors were diagnosed by other means and were confirmed by enteroscopy. Parker reported finding a large neurofibroma within the proximal jejunum [11]. Hashmi reported a 22-year-old woman presenting with melena [18]. The jejunal leiomyoma was diagnosed initially by angiography and was subsequently confirmed by push enteroscopy and enteroclysis. Shigematsu reported three patients with lymphangiomas of the small bowel diagnosed on small bowel series and subsequently confirmed on push enteroscopy [19]. Watatani reported, in 1989, a 73-year-old woman with nausea and vomiting in whom a small bowel series showed a distal duodenal lesion [20]. Push enteroscopy not only confirmed this lesion, but a biopsy was performed that revealed this to be adenocarcinoma preoperatively.

Push enteroscopy was also used to place jejunal feeding tubes. The initial idea was to carry a transgastric jejunal tube through a previous gastrostomy into the jejunum. Direct percutaneous jejununostomies were the next to be described. Nasojejunal feeding tubes were also placed. The enteroscope was advanced to the jejunum, a guidewire was advanced through the instrument and the instrument was removed leaving the guidewire. The wire was transferred through the nasal passage and then using the Seldinger technique, the nasojejunal tube was positioned. This was used for feeding as well as to place catheters for enteroclysis and to obtain cholangiograms in patients after Roux-en-Y hepatic jejunostomies. Polypectomies were described as well as surveillance of patient with polyposis syndromes.

The rope-way method of enteroscopy was the oldest method to totally intubate the small intestine [21, 22]. It was in 1972, 4 years after the first description of colonoscopy, that Classen reported this procedure. The technique involved having a patient swallow a guide string and allowing it to pass through the rectum. The string was then exchanged for a somewhat stiffer Teflon tube over which an endoscope was passed. A complete endoscopic examination was obtained with this method. The instruments were fully therapeutic including cauterization and polypectomy. Unfortunately, the exam was painful due to tightening of the guide-tube and often-required general anesthesia. Due to patient discomfort, length of time necessary for string passage and development of better-tolerated techniques, the rope-way method was abandoned. Classen abandoned the technique shortly after his first report and described it as a “rigorous procedure” that was “traumatic to the patient.” Video rope-way enteroscopes were also developed but these had the same limitations of the non-video versions [23].

Another development was endostomy, a procedure that involved creating an enterocutaneous fistula that could then allow a thin endoscope to intubate the small bowel [24]. Frimberger reported this technique in one patient. The fistulae were created using standard Ponsky gastrostomy techniques in the jejunum and in the cecum. After the tracts matured in 8–10 days, thin (4 mm diameter) prototype endoscopes were inserted through the jejunostomy and cecostomy to evaluate the intestine. Although innovative, this procedure was never accepted.

The last of the historical procedures is sonde enteroscopy. This was termed small bowel enteroscopy or long tube enteroscopy. The term sonde came from the French word for probe. In essence, it was an endoscopic Cantor tube, used for small bowel obstruction. A thin transnasal endoscope had a hood or balloon on its tip that allowed peristalsis to drag the instrument distally (Fig. 3.2). The endoscopic exam was performed during withdrawal of the scope. Development of sonde enteroscopy spanned nearly 13 years [25]. Prototype SSIF (sonde small intestinal fiberscope) I thru IV had narrow fields of vision (60°) and a large diameter (11 mm). Initially, a metal hood was placed at the instrument tip and used to induce distal passage. Subsequent prototypes had utilized a balloon at the tip that was inflated upon placement in the small bowel. Early enteroscopes were fitted with magnifying lenses to evaluate villi shape and were used in the diagnosis of tuberculosis and malabsorption states [26]. Attempts to introduce tip deflection capability in the fifth prototype made the instrument too stiff for distal intubation [27, 28]. Oral passage, which was required with these thick instruments, was associated with patient salivation, gagging, and considerable discomfort [29]. A thin, flexible, transnasal enteroscope was developed in 1986 [30] with a tip diameter of 5 mm and a length of 2,560 mm. The instrument’s forward angle of view was initially 90°, but was subsequently increased to 120°. This instrument, in contrast to a push enteroscope, had no biopsy or therapeutic capability and no tip deflection. An attempt to add biopsy capability to this instrument in the tenth prototype was successful, but targeting the biopsy remained a problem since there was no tip deflection [31]. The major standard sonde enteroscope, the SIF-SW (small intestinal fiberscope—sonde, wide) did not have this biopsy channel, but remained transnasally passed with a fisheye lens (Fig. 3.3). Video technology was also applied to sonde enteroscopy. Dabezies reported on a video sonde enteroscope used in seven patients [32]. The instrument’s tip measured 11 mm, due to the presence of the video chip, necessitating oral passage. The instrument did not use a balloon, and depth of intubation was limited.

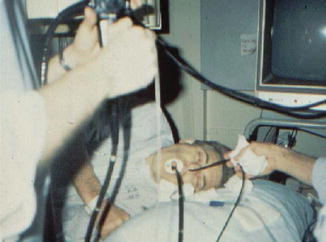

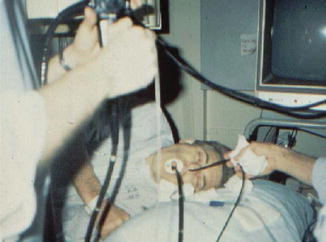

Fig. 3.2

Patient undergoing sonde enteroscopy while the instrument was carried into the small bowel by peristalsis

Fig. 3.3

X-ray of sonde enteroscopy with total small bowel intubation

The original technique to position a sonde enteroscope within the jejunum was to pass the instrument transnasally, lay the patient on their right side and follow the patient with sequential fluoroscopy. My first exposure to sonde enteroscopy was watching a videotape of Dr. Tada performing the examination on himself! A technique to rapidly place the enteroscope into the jejunum was developed to shorten the examination time. This rapid technique used a push enteroscope to grasp a suture affixed to the sonde instrument tip and actually “push” the scope into the jejunum (Fig. 3.4). The advantage of this technique was that it permitted total or near total small bowel intubation within 8 h and thus allowed the procedure to be performed on an ambulatory basis. The original technique averaged 24 h.

Fig. 3.4

Insertion of sonde enteroscope with orally passed colonoscope

Sonde enteroscopy proved itself useful in the evaluation of the patient with presumed small intestinal bleeding. Initially, Lewis and Waye reported results of the technique in 60 patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. In this report, a small bowel site of blood loss was detected in 33 % [33]. A later report by Lewis detailed results in 504 patients [34]. In patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, combined push and sonde enteroscopy documented findings in 42 % of patients. Eighteen percent of the lesions were found in the region covered by push enteroscopy but distal to the area examined by standard upper endoscopy. Twenty-six percent of the lesions were found in the remaining bowel examined by sonde enteroscopy. Vascular ectasias constituted 80 % of the findings overall and small bowel tumors accounted for 10 %. Several of the tumors discovered occurred in patients after a falsely negative enteroclysis [35]. Similar experience using sonde enteroscopy was reported by Barthel with a yield of 27.8 % in 18 patients [36], by Gostout with a yield of 26 % in 35 patients [37], and by Morris with a yield of 38 % in 65 patients [38].

Significantly, the nature of vascular lesions was better understood from these studies. Lewis reported an average age of 69 years in 102 patients with small intestinal angiodysplasias, without a sex predilection [33]. Angiodysplasias of the small bowel presented with either brisk or occult bleeding. Patients usually had only fecal occult blood test positivity or melena. Red or maroon blood per rectum was uncommon. Lewis reported that melena was the presenting sign in 64 % of 102 patients with bleeding small bowel angiodysplasias, while 36 % had occult blood in the stool. His findings also confirmed autopsy data by Meyer [39] who reviewed 218 angiodysplasias and found 2.3 % in the duodenum, 10.5 % in the jejunum, and 8.5 % in the ileum. Lewis also found that most patients had only a few vascular lesions that were countable, and all could be found within the same segment of small bowel. Diffuse lesions were much less common and were seen in less than 3 % of all patients with small bowel vascular lesions.

Despite numerous advances in sonde enteroscopy, it became clear that sonde enteroscopy had distinct disadvantages. The time required made it tedious for both patient and physician. Adhesions, strictures, and motility disturbances limited passive passage of the instrument. Even when complete small bowel intubation was achieved, total mucosal inspection was never complete. The lack of tip deflection and the inability to readvance the instrument once withdrawal had begun limited the mucosal view. Instruments also proved to be fragile and only one patient could be examined per day using the one instrument. Although this technology was a major advance and helped define obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, sonde enteroscopy was found to be inefficient. At its heyday there were 29 centers offering sonde enteroscopy, but by 1999 there were only 10, and today it is totally forgotten.

Intraoperative enteroscopy remains the fallback procedure to allow total small bowel endoscopic examination when other procedures are unsuccessful. Colonoscopes are routinely employed for this examination, though a push enteroscope may also be used (Fig. 3.5). The instrument does not need to be sterile, since the recommended technique involves peroral intubation of the small intestine. The proximal jejunum is intubated prior to the performance of the laparotomy, since once the abdomen is open, it may be difficult to advance the instrument around the ligament of Treitz due to excessive, and unopposed, bowing of the endoscope shaft along the greater curvature of the stomach. With oral intubation of an adult colonoscope, the endotracheal tube cuff may need to be deflated to permit passage of the wide caliber endoscope. Once the colonoscope is placed within the proximal jejunum, laparotomy is performed. A non-crushing clamp is placed across the ileocecal valve to prevent distention of the colon with insufflated air. Colonic distention can lead to difficulties with subsequent abdominal closure.