Since Hirschowitz and colleagues described the first flexible fiberoptic endoscopes, the technical explosion in fiberoptic endoscopy has produced instruments that are durable, safe, relatively comfortable, and capable of visualizing the gastrointestinal tract with great diagnostic accuracy.

The

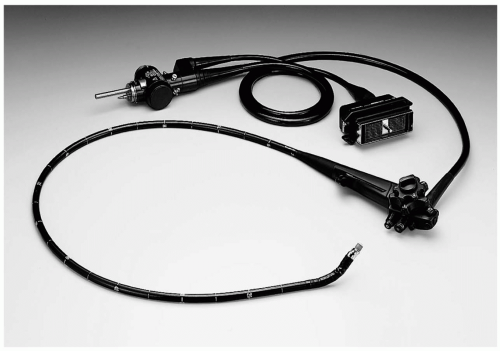

typical modern fiberoptic endoscope is a highly sophisticated instrument (

Fig. 5-1). The shaft is 8 to 12 mm in diameter. The fiberoptic bundles pass through the shaft to transmit light to the tip and the image to the endoscopist. In the handle of the endoscope are controls for maneuvering the tip and buttons to regulate irrigation water, air insufflation, and suction for removing air, secretions, and blood. An instrument channel allows the passage of biopsy forceps, small brushes for obtaining cytology samples, snares for removing polyps and foreign bodies, and devices to control bleeding.

The adaptation of endoscopes to video monitoring systems has been developed using computer chip technology and now is in routine use in all endoscopy suites. The endoscopist conducts the examination by viewing the video screen, not by looking directly through the fiberoptic system of the endoscope. The video screen also allows a variable number of people, including the patient if desired, to observe what the primary endoscopist is seeing, and the procedure can be videotaped for clinical and educational purposes.

During routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, the entire esophagus, stomach, and proximal duodenum are examined. Several therapeutic endoscopic techniques have been developed that allow endoscopists to treat bleeding lesions (see

Chapter 14) and relieve esophageal obstruction caused by benign or malignant processes. Endoscopic placement of gastric feeding tubes—percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)—has largely replaced surgical gastrostomy.

A variation of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), combines endoscopic and radiologic techniques to visualize the biliary and pancreatic ductal systems. ERCP methods also have been used therapeutically to perform sphincterotomy of the sphincter of Oddi, to remove common bile duct stones, and to place stents that bypass obstructing lesions.

During examination of the lower gastrointestinal tract by colonoscopy, a skilled endoscopist can reach the cecum in more than 95% of patients, and in many instances the terminal ileum can also be visualized. The major therapeutic capability of colonoscopy, popularized in the United States in the mid-1980s by President Ronald Reagan’s experience with a cancerous polyp, is polypectomy, usually by electrocautery.

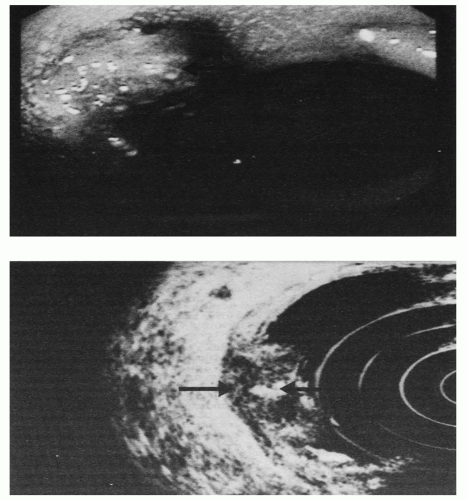

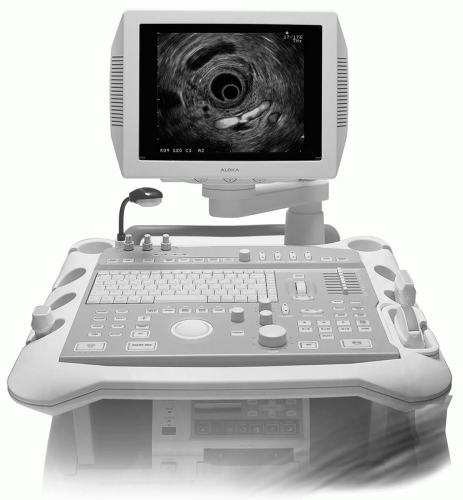

An important development in endoscopy is endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) (

Figs. 5-1,

5-2, and

5-3). High-frequency, high-resolution ultrasound transducers that are built into the tip of the endoscope can be passed to sites that are relatively close to the target organ. Applications include evaluation of lesions involving the esophagus, mediastinum, stomach, duodenum, pancreas, colon, and rectum. EUS compares favorably with computerized tomography in tumor staging and determination of lymph node involvement. Indications for EUS are summarized in

Table 5-1. Also, lymph nodes in the thorax and abdomen may be biopsied and pancreatic pseudocysts may be drained using EUS.

I. UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

A. Indications.

Several conditions in which upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, also known as

esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), may be useful in making a diagnosis are listed

Table 5-2. Opinions differ among physicians as to whether and when EGD should be performed for a given condition. For example, some physicians order an upper gastrointestinal x-ray series initially in the evaluation of a patient who has dyspeptic complaints. Other physicians treat a patient with dyspepsia empirically with antacids or some other acid-reducing medication without obtaining a diagnostic study, unless the patient is elderly or has evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss, or vomiting, suggesting gastric outlet obstruction. An EGD might subsequently be arranged if the patient does not respond to treatment in a reasonable time or develops bleeding, weight loss, or vomiting.

B. Contraindications.

EGD should not be performed if a perforated viscus is suspected or if the patient is in shock, is combative, or is unwilling to cooperate (

Table 5-3).

C. Preparation of the patient.

Elective EGD should be performed after the patient has fasted for 6 or more hours to ensure an empty stomach. However, this rule does not apply to emergent situations such as in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding or with foreign body impaction of the esophagus or when food and clots may fill the esophagus and/or stomach and these may need to be immediately removed endoscopically.

In conscious patients, a topical anesthetic may be applied to the pharynx to numb the gag reflex. Conscious sedation (i.e., intravenous midazolam [Versed], meperidine [Demerol], or fentanyl) often is administered as a sedative. Tolerances for midazolam vary widely. Older and severely ill patients may become sedated or develop respiratory depression even at low doses. Thus, a test dose of 1 to 2 mg initially is advisable. Most patients require 2 to 5 mg to achieve adequate relaxation. The doses of meperidine and fentanyl also vary depending on the patient. Most patients require 12.5 to 100 mg. Because patients are likely to feel sleepy for an hour or more after the procedure, it is required that the outpatients arrange for transportation home with an accompanying person after EGD.

Deep sedation, using Propofol IV, may be used in selective patients with medical or psychiatric comorbid conditions.