, Liqing Yao1 and Xinyu Qin2

(1)

Endoscopy Center, Zhongshan Hospital Fudan University, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China

(2)

General surgery, Zhongshan Hospital Fudan University, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China

Abstract

ESD in esophagus can be difficult, time-consuming due to its narrow lumen, weak mucosa, no serosa, rich submucosal vessels, and is easily influencing by the heartbeat and breathing, especially in upper esophageal lesions [1]. Thus ESD for esophageal lesions should be carried out in centers with expertise in endoscopic resection, management of potential complications [2].

4.1 ESD for Superficial Esophageal Lesion

ESD in esophagus can be difficult, time-consuming due to narrow lumen, weak mucosa, lack of serosa, rich submucosal vessels. Furthermore, breathing and heartbeat makes procedure difficult in upper esophagus [1]. Thus ESD of esophageal lesions should be carried out in centers with expertise in endoscopic resection and management of potential complications [2].

4.1.1 Indication [3, 4]

Lymph node metastasis and technical resectability are two important factors in patient selection.

1.

Absolute indications: high-grade intraepithelial neoplasms (HGINs) [including noninvasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) (carcinoma in situ, m1)] and intramucosal invasive SCCs limited to the lamina propria mucosae (m2) without vessel infiltration, and not exceeding two-thirds of the circumference.

2.

Relative indications: Deeper lesions of 200 μm in the submucosa (m3 and sm1) without clinical evidence of lymph node metastasis, or HGIN or m2 lesions exceeding two thirds of the circumference. In this group of patients, general status and comorbidities should be considered.

4.1.2 Equipment

1.

Single-channel gastroscope (GIF-H260 or GIF-Q260J, Olympus).

2.

A transparent cap (D-201-11304, Olympus) is attached to the tip of the gastroscope to provide direct views of the submucosal layer.

3.

ESD Knives- insulated-tip electrosurgical knife (KD-611L, Olympus), hook knife (KD-620LR, Olympus), Flex knife (KD-630L, Olympus), or hybrid knife (ERBE, Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany).

4.

Injection needle (NM-4L-1, Olympus), grasping forceps (FG-8U-1, Olympus), snare (SD-230U-20, Olympus), hot biopsy forceps (FD-410LR, Olympus), clips (HX-610-90, HX-600-135, Olympus; Resolution TM, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA), high-frequency generator (ICC series or VIO 300D, ERBE), and argon plasma coagulation unit (APC300, ERBE).

5.

For submucosal injection, we use a saline mixture (including 100 ml of normal saline, 1 ml of indigo carmine, and 1 ml of epinephrine). Glycerol and Fructose injection (a mixture of 10 % glycerol, 5 % Fructose and 0.9 % NaCl), or hyaluronic acid solution have been used by other centers.

Carbon dioxide is used to decrease the rates of gas-related complications.

4.1.3 Preoperative Endoscopic Diagnosis

4.1.3.1 Lugol Iodine Staining

Esophageal squamous epithelial cells are rich in glycogen, hence turn brown when sprayed with Lugol’s iodine liquid. Abnormal area such as columnar change, or with inflammatory edema, atrophy, atypical hyperplasia, or cancer lead to glycogen depletion resulting in absent or reduced staining (pale) with iodine (Fig. 4.1). Thus Lugol iodine staining helps to identify the margin of lesion clearly. Lugol iodine is irritant and not used routinely in tumor screening.

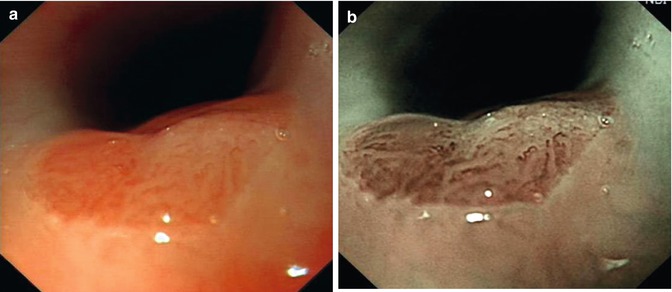

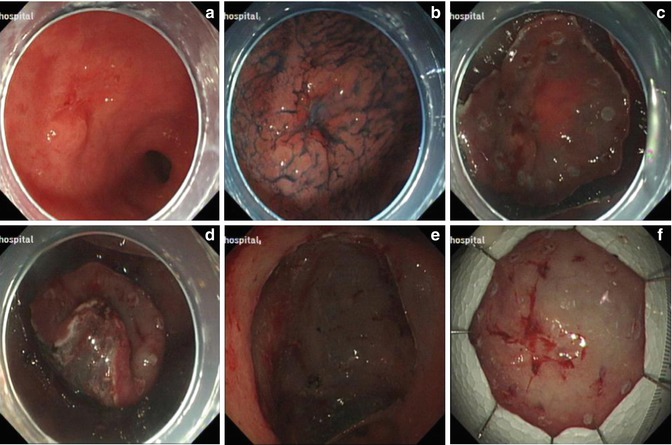

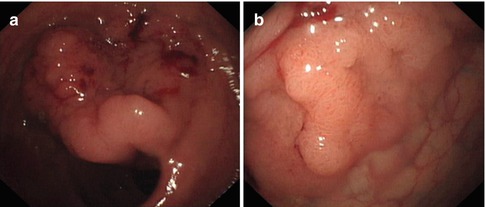

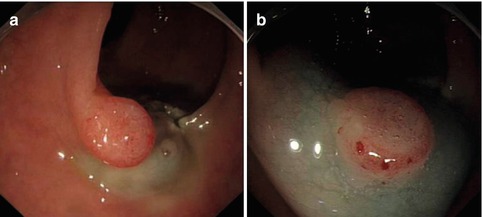

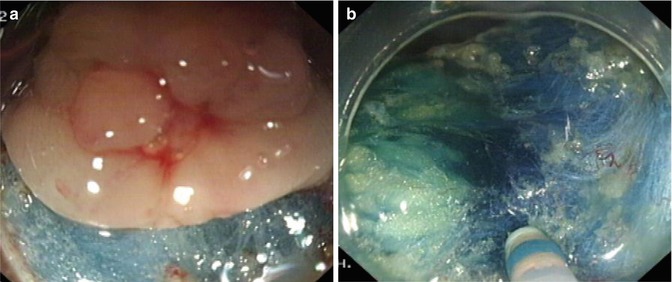

Fig. 4.1

Lugol iodine staining for a superficial esophageal lesion. (a) White light endoscopy showed an erosive lesion at the middle esophagus. (b) The lesion was not stained after iodine spray

4.1.3.2 Narrow Band Imaging and Magnifying Endoscopy

NBI is a novel optical technique that enhances the diagnostic ability of endoscope by highlighting the intraepithelial papillary capillary loop (IPCL) using narrow bandwidth filters [5]. The NBI filter sets (415 and 540 nm) are selected to obtain fine images of the microvascular structure. Because 415 nm is the hemoglobin absorption band, capillaries on the mucosal surface can be seen most clearly at this wavelength. NBI is able to represent more clearly both capillary patterns and the boundary between different types of tissue, which are necessary for diagnosing a tumor in its early stage. This improves the visibility of superficial capillaries and mucosal structures, which allows clear visualization of the lesion and predication of the invasion depth, hence facilitates targeted biopsies (Fig. 4.2). In combination with magnifying endoscopy, NBI is useful to demarcate the lesion margin.

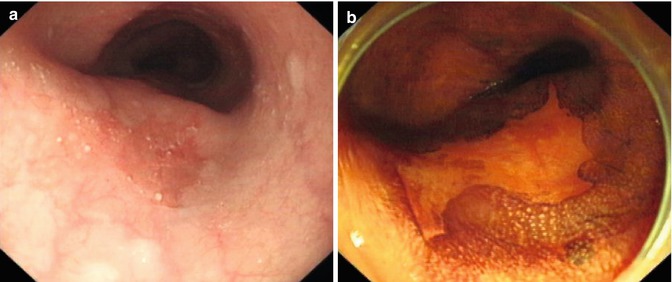

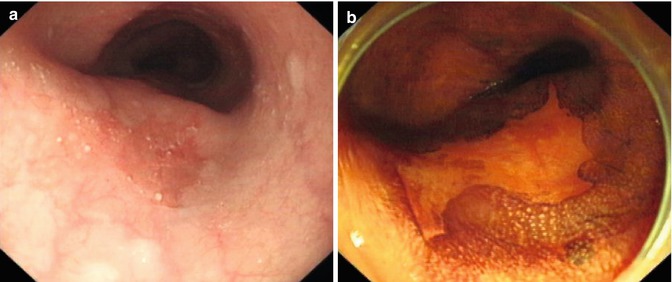

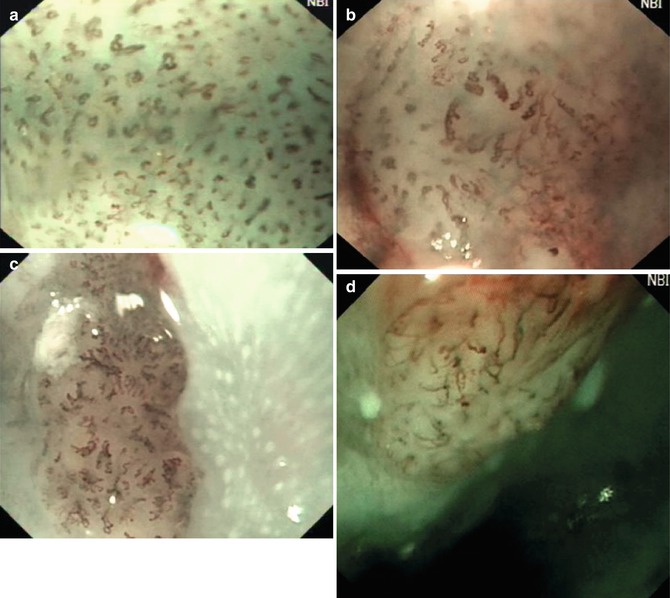

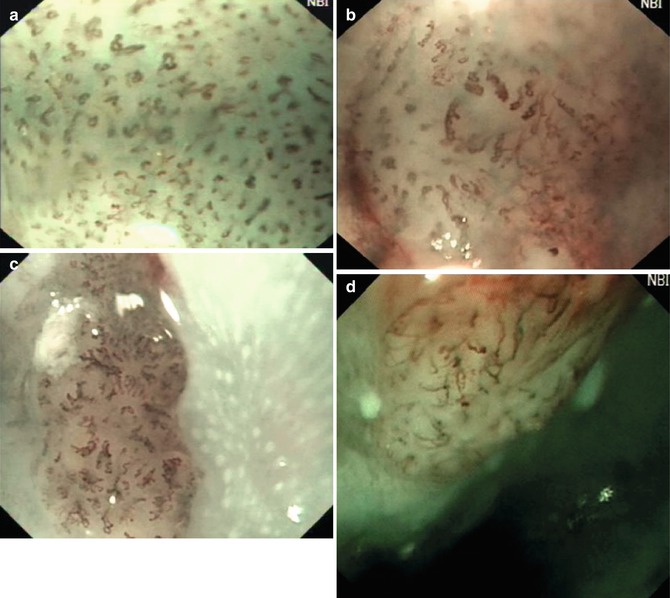

Fig. 4.2

NBI for the diagnosis of Barrett esophagus. (a) White light. (b) NBI

IPCL: As demonstrated by Inoue et al., magnifying endoscopic findings were classified into five types according to the degree of change in IPCL pattern. Changes include dilatation, tortuosity, and/or caliber change of individual IPCL, or multiple IPCLs of various shapes. Type I is a normal IPCL pattern. Squamous mucosa with this type is usually well stained by iodine solution. Type II is minimal dilatation and elongation of IPCL, and stains lightly by iodine-dye chromo endoscopy. This finding corresponds to esophagitis. In Type III, minimal changes in IPCL are observed, and the lesion is shown by iodine-dye chromoendoscopy as an unstained area. In Type IV, three of the four abnormal IPCL patterns are present at magnifying endoscopy, and the mucosa is unstained by iodine. Types III and IV correspond to, respectively, mild and severe dysplasia. In Type V, all four abnormal IPCL factors are present and distinct; the Type V pattern signifies the presence of cancer. Among the lesions of Type V, Type VI exhibits severe changes in all four patterns, which corresponds to m3 or sm1 invasion. In Type VN, the structure of the IPCL is completely destroyed and abnormal vessels are present. This type of lesion, cancer invades deeply into the submucosal layer (Fig. 4.3) [6].

Fig. 4.3

NBI magnifying images of early esophageal cancer. (a) IPCL being dilated with different diameter and shape (dysplasia and m1 cancer). (b) IPCL being stretched (m2 cancer). (c) IPCL being stretched (m3 cancer). (d) IPCL being broken with oblique extension (sm1 cancer)

4.1.4 Operating Procedure

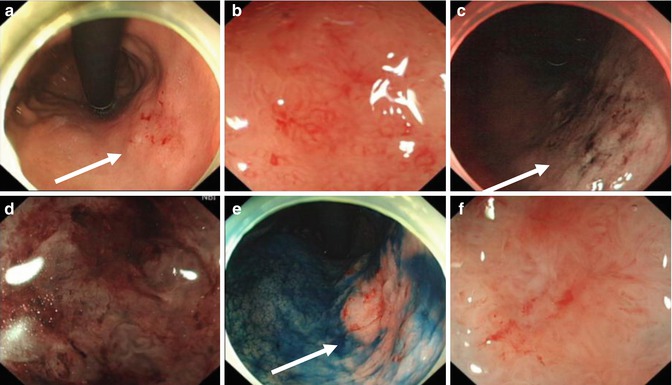

Procedure is carried out under general anesthesia. First step is to spray with Lugol iodine to demarcate the margin of the lesion. Residual reagent is removed by suction to prevent aspiration. Alternatively, targeted lesions are marked using cautery to ensure optimal visualization after submucosal injection. ESD procedure in esophagus is principally the same as in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract except coagulation power setting is low because the esophageal mucosa is thin. Procedure consist of five steps: marking, submucosal injection, mucosal precutting, submucosal dissection and wound management (Fig. 4.4).

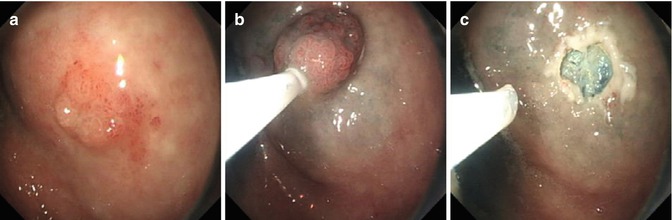

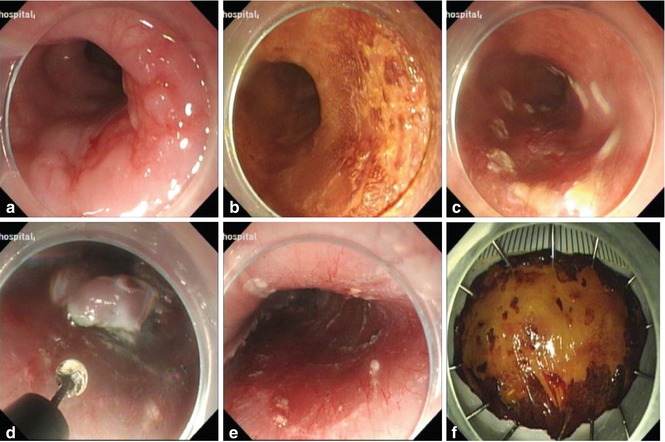

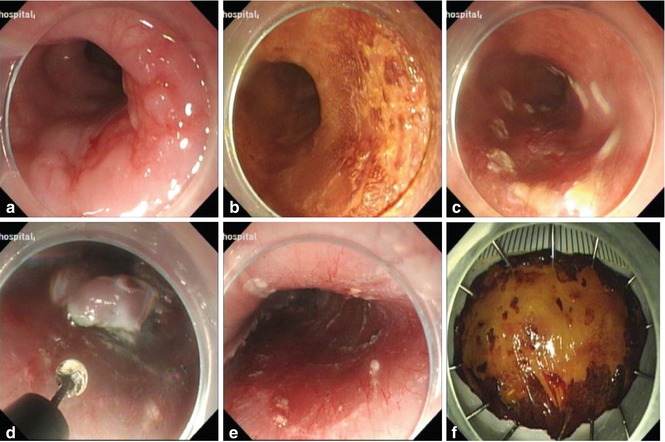

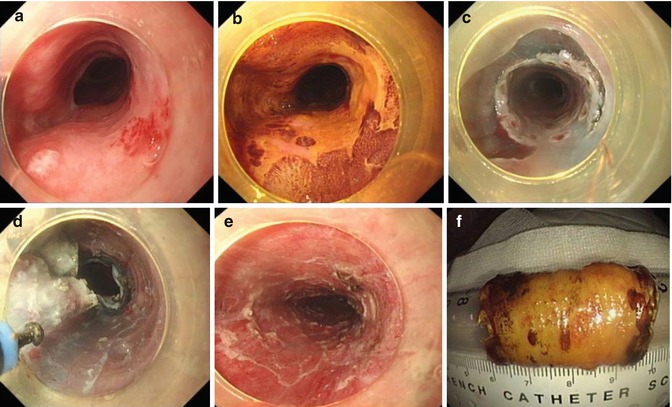

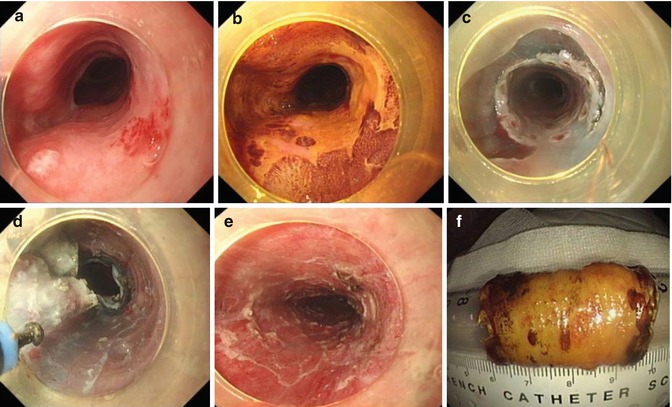

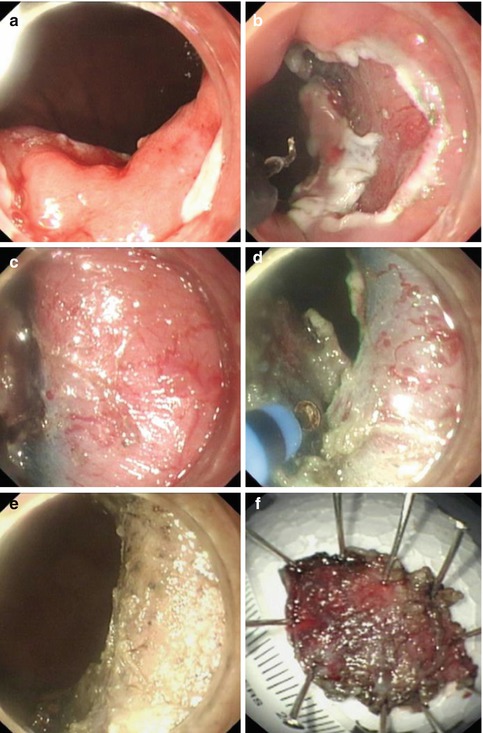

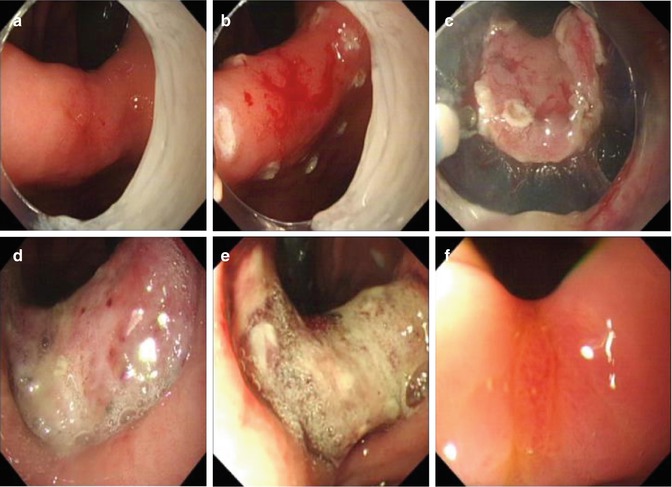

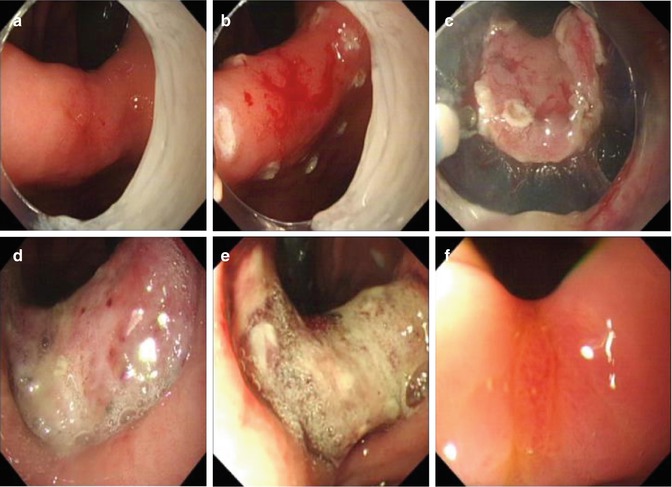

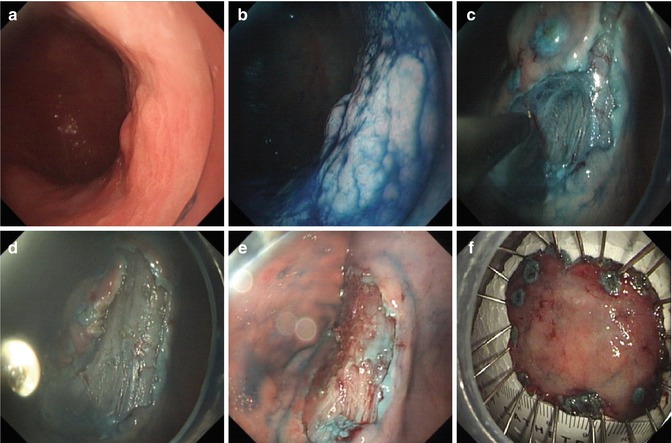

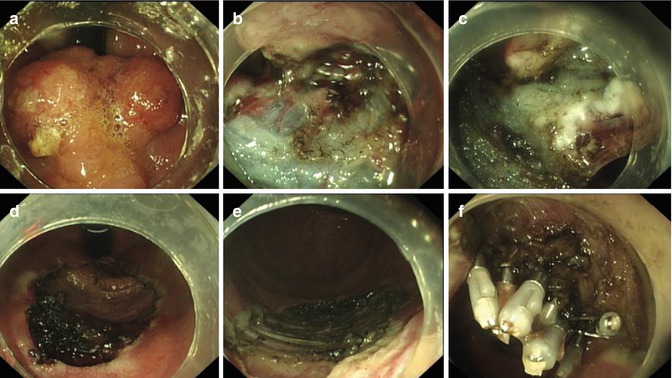

Fig. 4.4

ESD procedure for an erosive lesion in lower esophagus using IT knife. (a) Esophageal lesion. (b) After Lugol staining. (c) Marking the margin. (d) Dissection the lesion along the submucosal layer with IT knife. (e) The wound after ESD. (f) Resected specimen

4.1.4.1 Marking

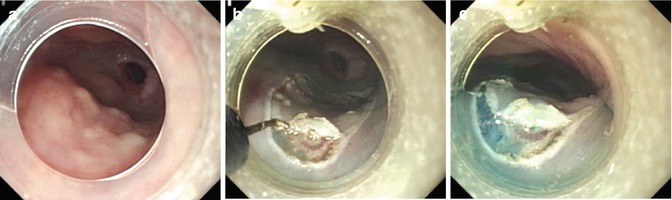

To ensure en bloc resection, the first step of ESD is to mark the resection margin clearly. For superficial lesion with a clear border, we directly mark the margin. For lesion without a clear border, lugol iodine staining or NBI is used to visualize the margins. Marking points are made 2–5 mm outside the demarcation of the lesion using APC or tip of ESD knife (Fig. 4.5).

Fig. 4.5

Making. (a) Esophageal lesion. (b) After Lugol spraying. (c) Marking the margin using APC

4.1.4.2 Submucosal Injection

Submucosal bleb is formed, using a 23-gauge needle, with saline mixture [7]. To lift the lesion, multi-point injections are made to separate the lesion from muscular layer. This makes the dissection easier, and reduces the risk of perforation and bleeding. The esophageal lumen is narrow, hence excessive injection is avoided to operating space. We use injection 2 ml is injected at each point to left the entire lesion (Fig. 4.6). Sometimes, it is easier to start mucosal precutting after part of lesion has been injected and lifted. We avoid deep needle insertion to prevent spilling of solution into mediastinum. Lesions with no lifting sign after sumucosal injection may be not suitable for ESD treatment because of either severe inflammation or submucosal invasion.

Fig. 4.6

Appropriate injection volume to ensure adequate endoscopic view. (a) Esophageal lesion. (b, c) Mucosal precutting was performed by hook knife

4.1.4.3 Mucosal Precutting

In view of the limited endoscopic view in the esophagus, it is very important to determine the starting point of incision. The anal half of the incision is completed first, followed by the oral half. Incision of the left-wall is carried out first, otherwise lesion is submerged with fluid due to gravity, that can lead to hinderance of endoscopic views. After lifting the lesion with submucosal injection part of the mucosa along the lateral border of marked points is incised using ESD knife first. Then a circumferential mucosal incision is made around the lesion using the IT knife [8] (Fig. 4.7). The tip of the knife should be less than 2 mm. Multiple ESD knives have been developed and used, such as Flex knife, TT knife and needle knife.

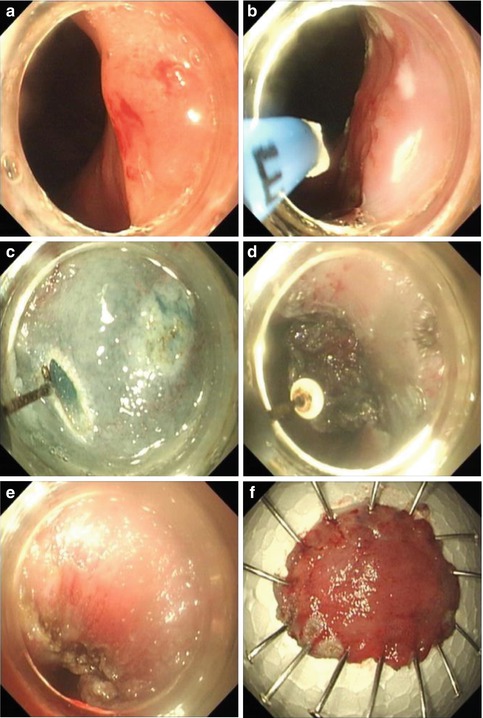

Fig. 4.7

Mucosal precutting. (a, b) Esophageal lesion. (c) A circumferential mucosal incision was done around the lesion. (d) The wound after ESD. (e) Resected specimen

During the incision, bleeding can often be treated by forced coagulation using the tip of the knife or a hemostatic forceps. Perforation is often due to the inadequate submucosal injection or too deep cutting [9].

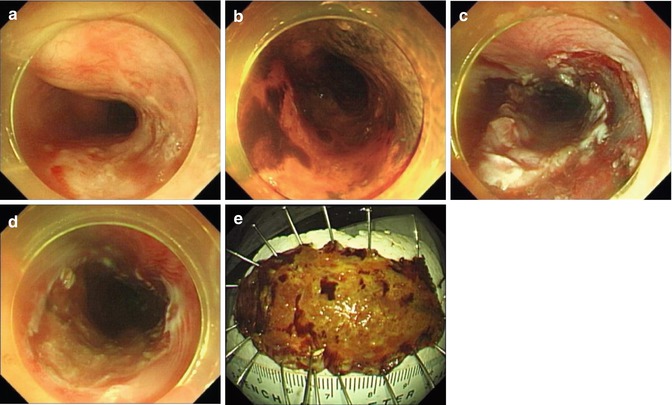

4.1.4.4 Dissection

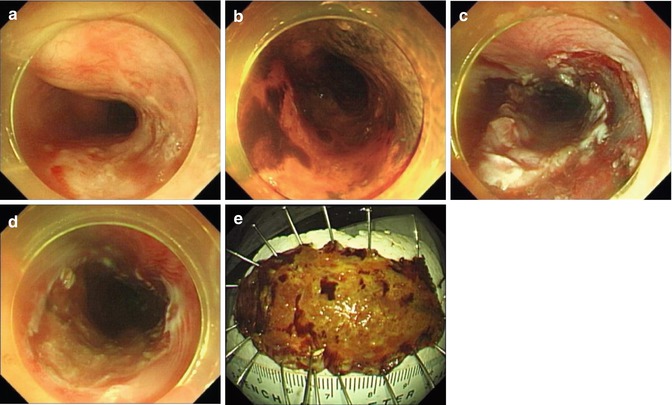

After separating the lesion from the muscular propria by submucosal injection, the submucosal connective tissue, including the whole marked outer circumference of the target lesion, is cut, and the target lesion, is carefully dissected from the submucosal layer under direct vision. Dissection of the submucosa is begun from the oral end to the anal end. Both sides of the lesions should be dissected at the same time, to facilitate the dissection and ensure en block resection (Fig. 4.8). A transparent cap is used lift the mucosal flap to expose the submucosal layer and to provide space to facilitate dissection. Injections are repeated as needed during the procedure to ensure total removal of the lesion (Fig. 4.9).

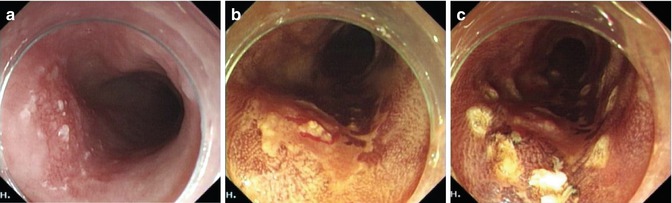

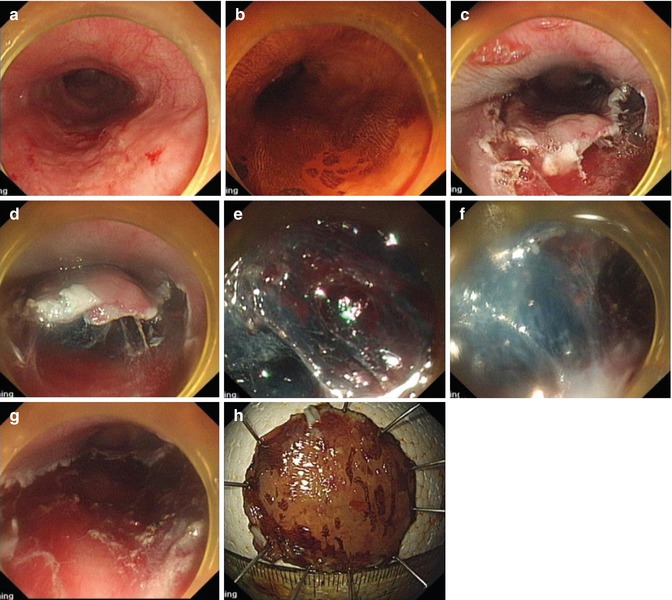

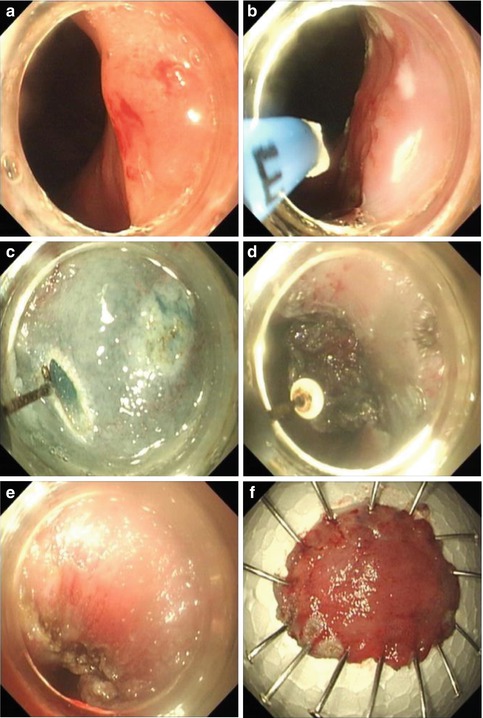

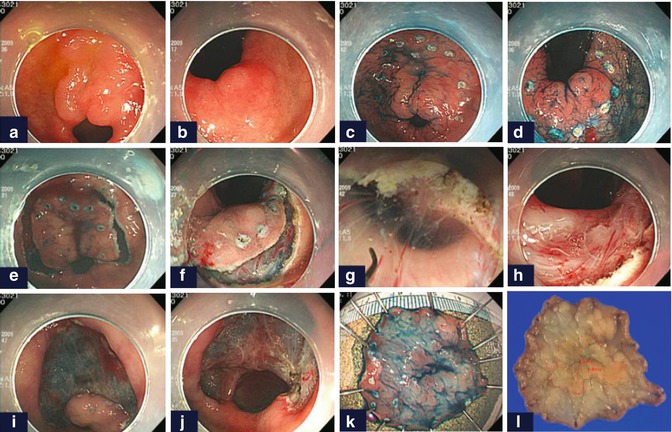

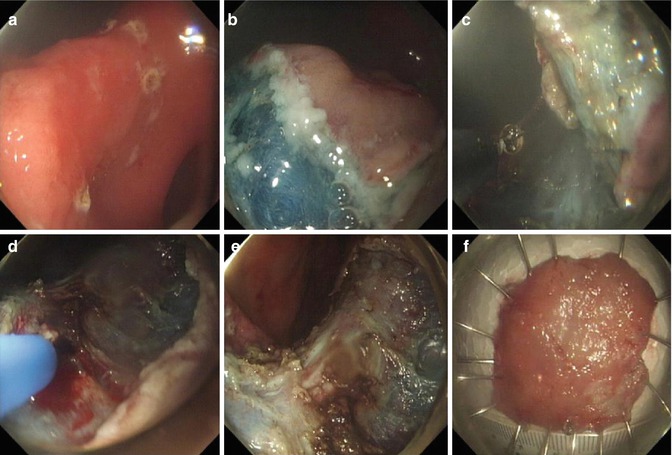

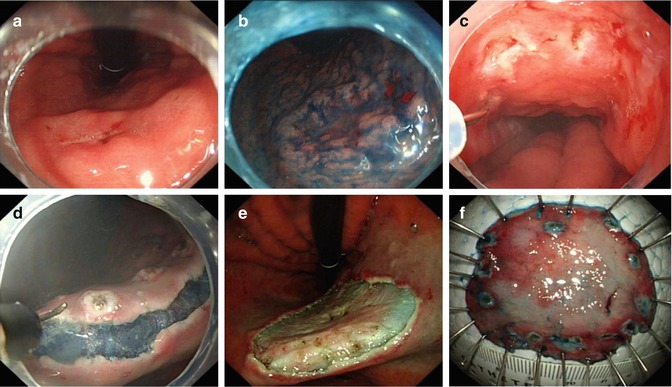

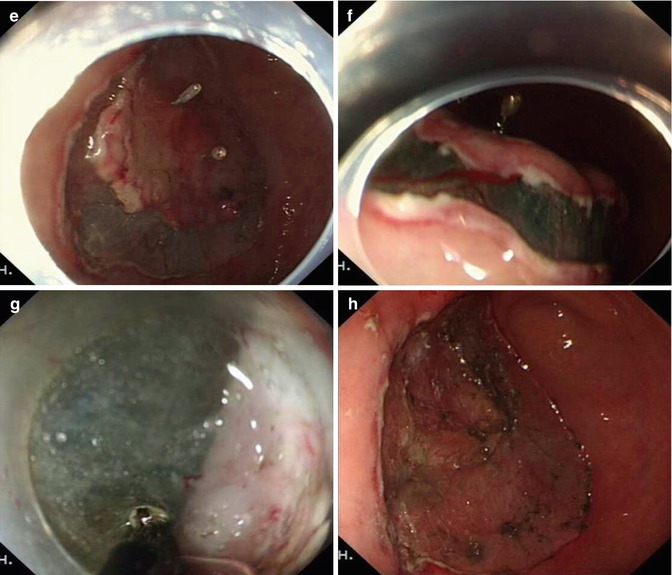

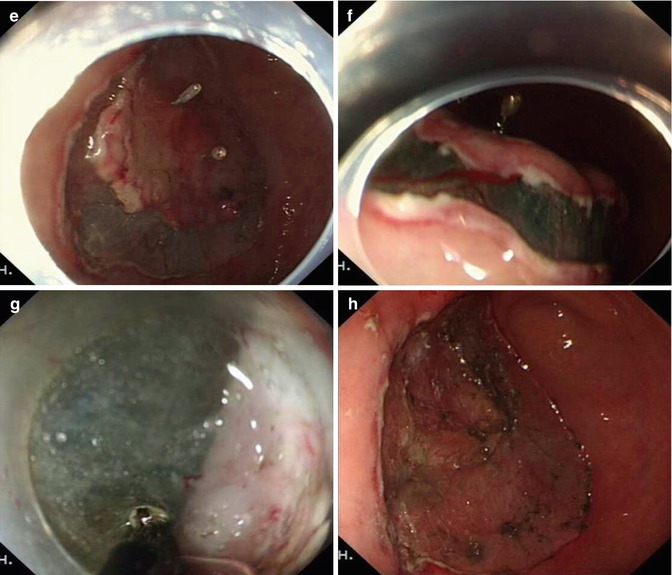

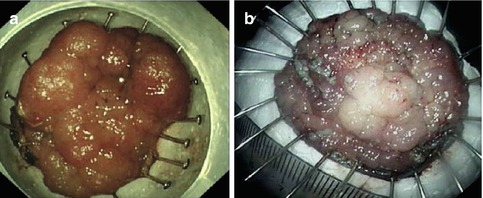

Fig. 4.8

ESD procedure for an esophageal lesion. (a) Esophageal lesion. (b) Lugol staining. (c, d) Mucosal precutting. (e, f) The lesion was dissected from the submucosal layer under direct vision, from the oral side to the anal side. (g) Management of the wound after ESD. (h) Resected specimen.

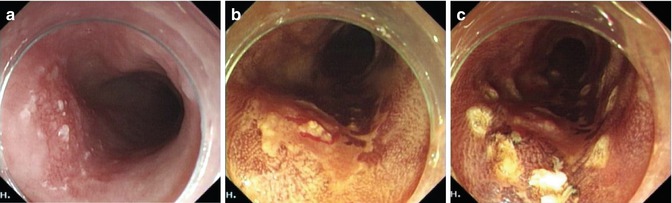

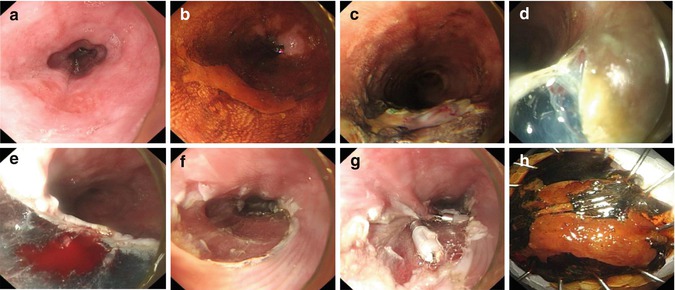

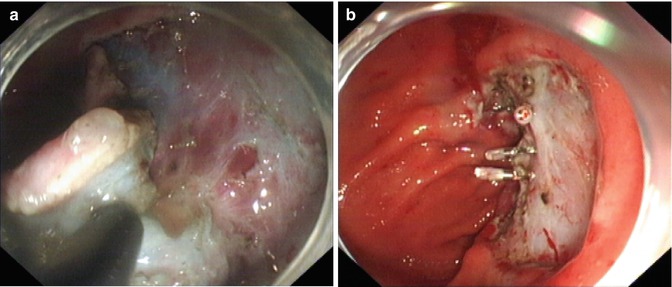

Fig. 4.9

Repeated injections during dissection. (a, b) An esophageal lesion. (c) Mucosal precutting. (d–f) Injections were repeated as needed to expose the submucosal layer and provide sufficient space for dissection. (g) The wound after ESD. (h) Resected specimen

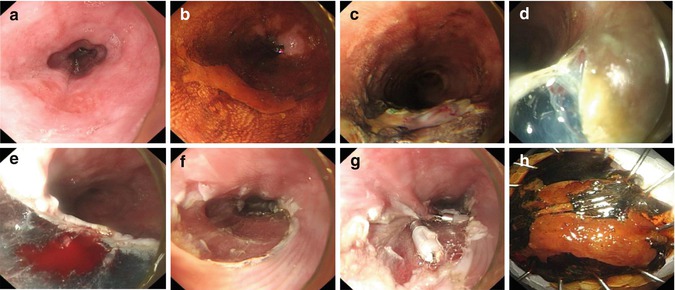

It is extremely important to prevent and stop bleeding during dissection. Once bleeding starts, the endoscopic view is hampered and any blind hemostasis attempt may eventually lead to perforation. Immediate minor bleeding can be treated successfully by grasping the bleeding vessels with Coag forceps. Direct coagulation with the tip of knife can be done for small vessels in the submucosa. Metallic clips are often deployed for more brisk bleeding (Fig. 4.10). Because of very thin esophageal wall, there is risk of perforation with coagulation hemostasis. The water-jet system is used to identify visible bleeding vessels for targeted hemostasis to prevent esophageal perforation. Blind coagulation hemostasis increases the risk of perforation (Fig. 4.11). The esophageal wound is carefully inspected to ensure the complete resection (Fig. 4.11).

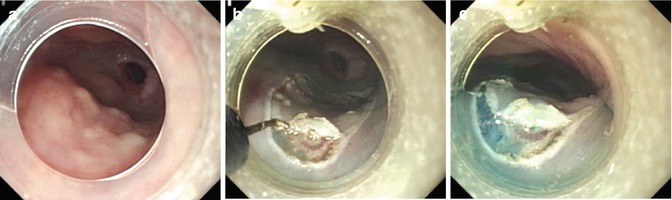

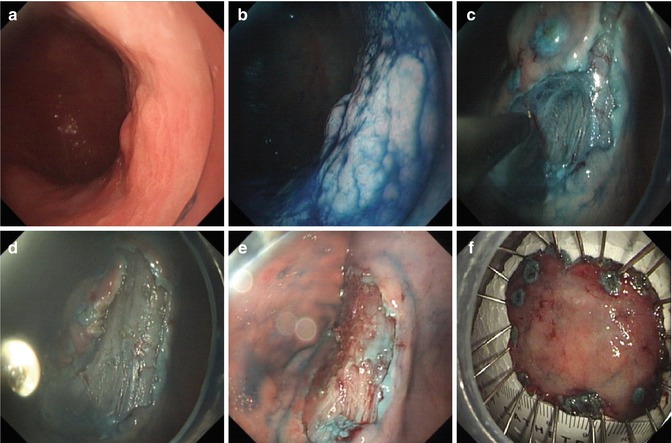

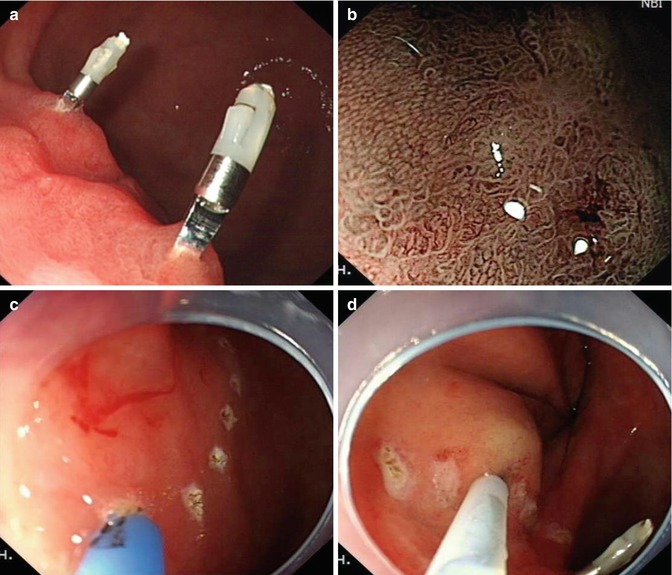

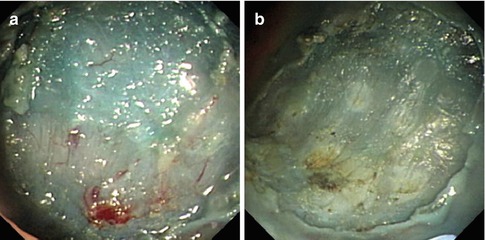

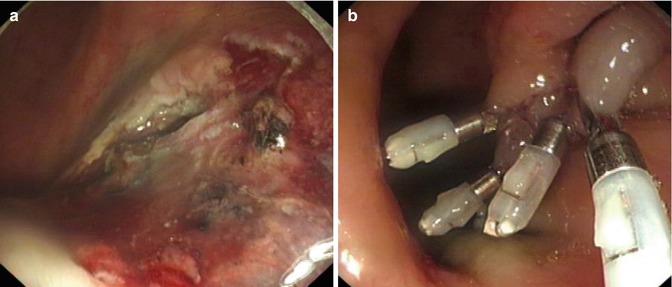

Fig. 4.10

Metallic clip was used for brisk bleeding during dissection. (a, b) Esophageal lesion. (c) Marking. (d) Mucosal precutting and dissection. (e) Metallic clip was used for brisk bleeding. (f) Resected specimen

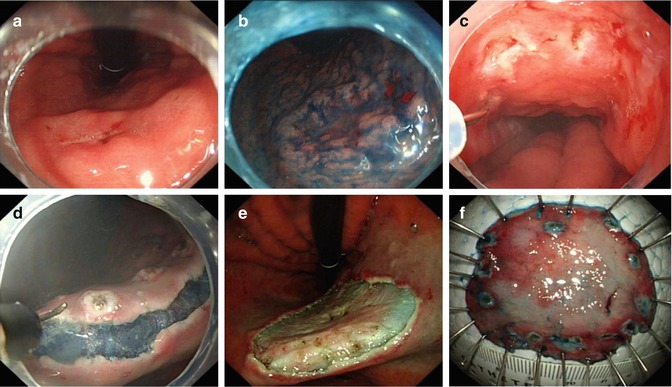

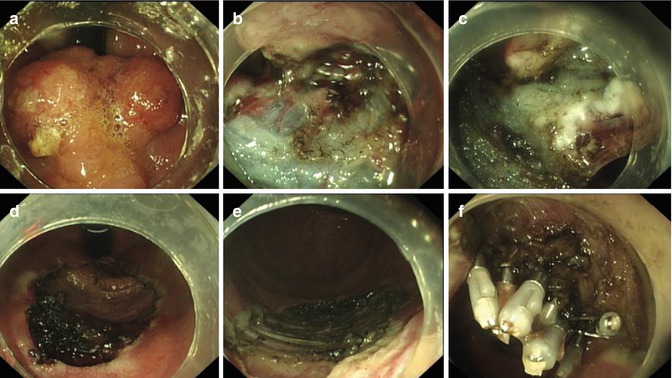

Fig. 4.11

Case illustration of Water-jet assisted ESD by hybrid knife. (a, b) A very large lesion of the esophagus (whole of the circumference, 6 cm long). (c, d) Mucosal incision and dissection were made using hybrid knife. (e) The wound after ESD. (f) Total removal of the lesion was confirmed by staining the resected specimen with Lugol

4.1.4.5 Wound Management

After complete resection, all visible blood vessels and potential bleeding sites are coagulated using Coag forceps and argon plasma coagulation and large vessels are clipped. Small wound can be closed with clips to prevent delayed perforation.

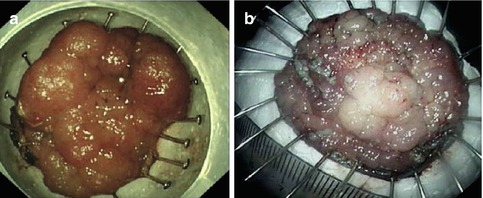

4.1.4.6 Pathological Evaluation

The resected specimen is stretched smoothly by several pins on a cork board. After taking an endoscopic image, the specimen is fixed with 10 % formalin for further pathological examination. Paraffin-embedded tumor specimens are sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Tumor resection is deemed microscopically complete when both lateral and deep resection margins are negative for tumor tissue.

4.1.5 Postoperative Management and Follow-up

Postoperative patients are observed for chest pain, dyspnea, cyanosis, abdominal pain or distention, and signs of peritonitis. If stable, patients allowed clear fluid the day after procedure and semi-solids from the day 2. Regular diet is allowed 2 weeks after procedure. Patients are prescribed PPI medication. Follow-up endoscopy is scheduled at 1 month to ensure complete resection. Subsequent additional treatment is decided based on endoscopic and histopathological findings. Serial endoscopic examination is carried out at 3, 6, and 12 months and annually thereafter to check for recurrence [10]. However, patients at high risk of recurrence, such as with multifocal lesions receive 6-monthly endoscopic surveillance. Patients with high risk for nodal or distant metastasis, such as with m3 lesion, also undergo annual CT imaging.

ESD in esophagus is safe and effective but requires significant expertise.

4.2 ESD for Early Gastric Cancer

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined as being confined to the mucosa or the submucosa, regardless of the presence or absence of regional lymph node metastasis. The early diagnosis of EGC is becoming easier due to the rapid development of endoscopic techniques, including chromoendoscopy, narrowband imaging, magnifying endoscopy, confocal microscopy and autofluorescence imaging. Endoscopic resection is gradually becoming the obvious choice, which is significantly less invasive than conventional surgical interventions. With new technique of ESD, en bloc resection is possible. Large tumors, and tumors with ulcers can be resected with lower recurrence rate than conventional endoscopic resection procedure. Thus, ESD is considered the gold standard for the treatment of EGC, particularly in Asian countries. The trend and new technology in the field of ESD focuses on developing novel instruments or methods to overcome technical difficulty, managing complications, as well as predicting and treating local recurrence/distal metastasis after ESD.

4.2.1 Indication [11]

Tumors of the following categories have a very low possibility of lymph node metastasis, hence ESD is indicated as a standard treatment.

1.

A differentiated-type adenocarcinoma without ulcer (UL(−)), of which the depth of invasion is clinically diagnosed as T1a and regardless of the diameter.

2.

Tumors clinically diagnosed as T1a and of differentiated-type, with ulcer (UL(+)), but measuring ≤3 cm in diameter.

3.

Tumors clinically diagnosed as T1a and of undifferentiated-type, UL(−), and ≤2 cm in diameter.

4.

Local mucosal recurrence after EMR/ESD for tumors fulfilling the indication criteria could be treated by another ESD.

5.

Tumors clinically diagnosed with SM1 invasion in elderly patients not fit for surgery can be considered as a relative indication for ESD.

The resection is judged as curative when all of the following conditions are fulfilled: en-bloc resection, negative horizontal margin, negative vertical margin, no lympho vascular infiltration, and:

1.

Tumor size >2 cm, histologically of differentiated type, pT1a, UL(−), or

2.

Tumor size ≤3 cm, histologically of differentiated type, pT1a, UL(+), or

3.

Tumor size ≤2 cm, histologically of undifferentiated type, pT1a, UL(−), or

4.

Tumor size ≤3 cm, histologically of differentiated-type, pT1b (SM1, <500 μm from the muscular is mucosae).

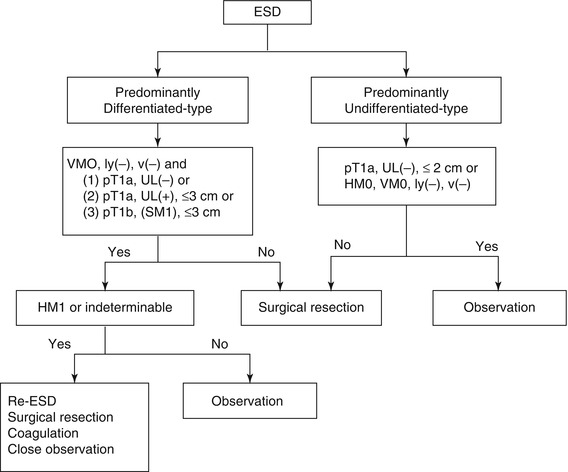

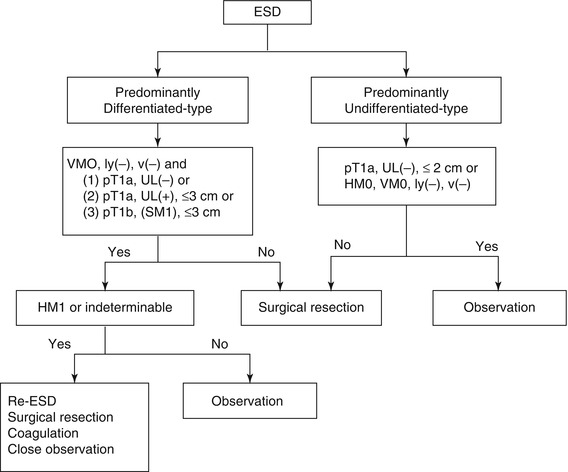

When the resections are regarded as non-curative additional surgical treatments should be recommended (Fig. 4.12). However, for the cases after en-bloc resection of a differentiated-type carcinoma with positive horizontal margin (HM1) as the only non-curative factor, which actually carry a very low risk of harboring lymph node metastasis, nonsurgical treatments such as repeated ESD, endoscopic coagulation using LASER or argon-plasma coagulator, or close observation expecting a burn effect of the initial ESD could be proposed as alternatives and discussed with the patients.

Fig. 4.12

Flow chart of the treatments after ESD. HM horizontal margin, VM vertical margin (Reproduced with permission from Gastric Cancer [11])

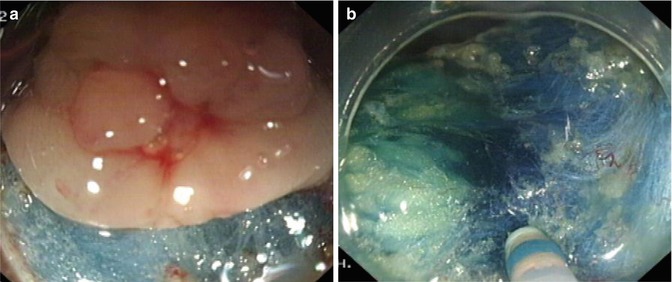

4.2.2 Preoperative Endoscopic Diagnosis

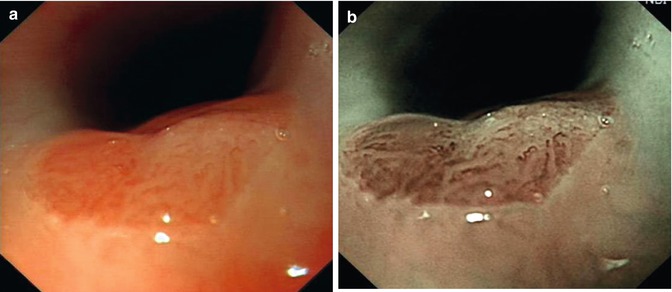

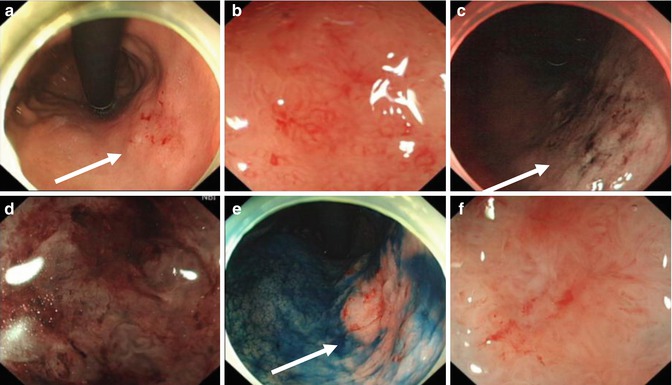

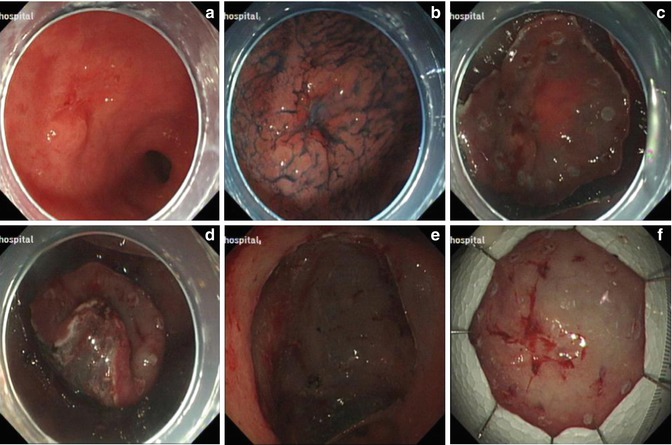

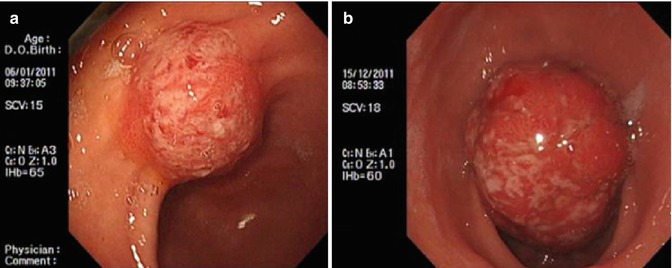

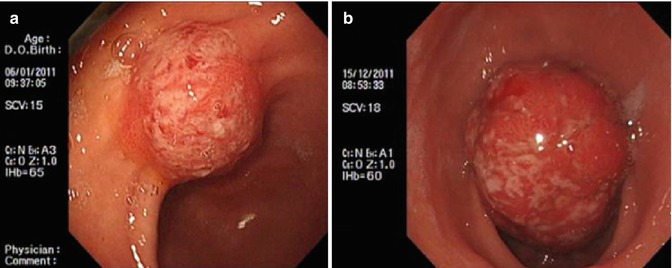

Selection of appropriate lesions is crucial before ESD, and the diagnostic skills to lesion characterize are of great importance. Using magnifying endoscopy, chromoendoscopy, narrowband imaging (NBI), and etc., we can assess lesion surface vascularity and pit pattern in detail and therefore enable correct diagnosis of lesion type, depth and suitability for endoscopic treatment (Fig. 4.13).

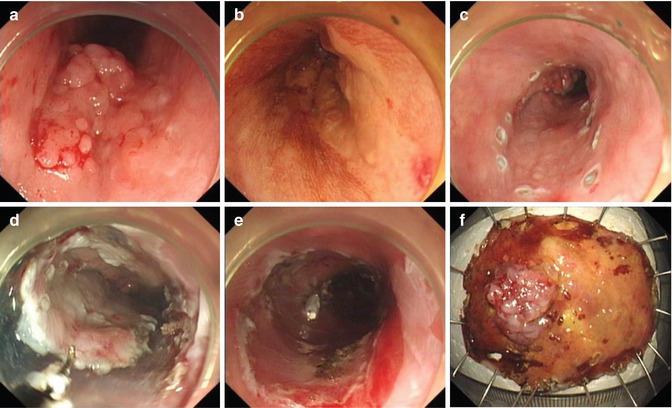

Fig. 4.13

Endoscopic diagnosis before ESD using magnifying endoscopy, NBI, and indigo carmine staining. (a) White light. (b) Conventional magnifying endoscopy. (c) NBI. (d) NBI and magnifying. (e) Indigo carmine staining. (f) Indigo carmine staining and magnifying (arrows point towards abnormal areas)

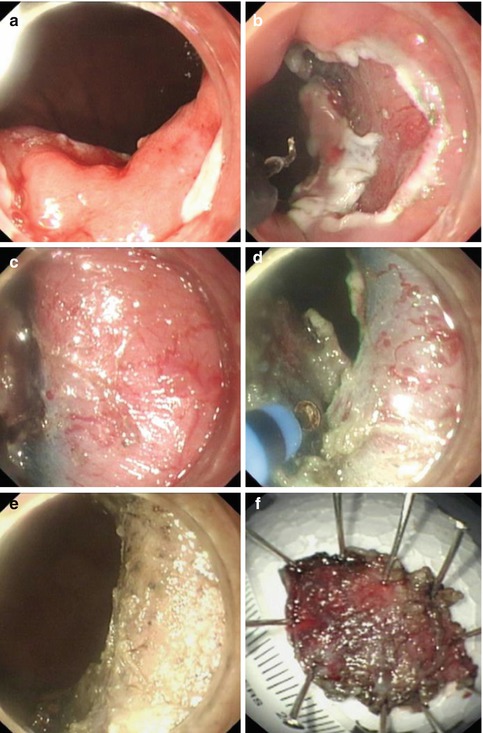

4.2.3 Operating Procedure

ESD for EGC consists of four steps: making, injecting fluid into the submucosal layer to separate it from the muscle layer, circumferential cutting of the mucosa surrounding the lesion, and submucosal dissection of submucosa under the lesion (Fig. 4.13). EGC is first identified and demarcated using white-light endoscopy, NBI and chromoendoscopy, and then marking around the lesions is carried out by using a standard needle knife (or a hook, flex, triangle-tipped, flash knife, or APC). After injection to raise submucosal layer, circumferential mucosal cutting outside the marking dots is performed with an IT or hook knife. After completion of the circumferential cutting, the solution is injected to raise submucosal. Then, the submucosal layer under the lesion is dissected. A cap attachment is useful for creating counter traction, making it easier to access and view the submucosal tissue. Complete endoscopic submucosal dissection can achieve a large one-piece resection. Finally, the resected specimen is retrieved with grasping forceps or a snare.

4.2.3.1 ESD for Lesions at the Esophagogastric Junction

The esophagogastric junction (EGJ) is regarded as a difficult and risky location for ESD due to its narrow lumen, sharp angle and very rich small vessels (Fig. 4.14).

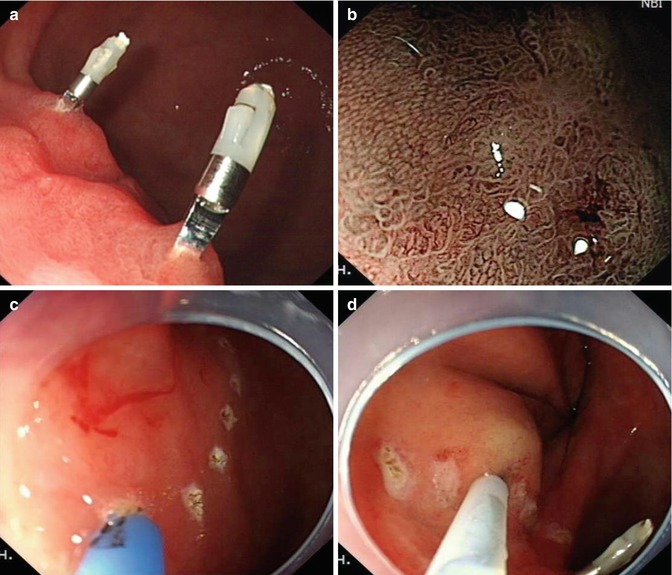

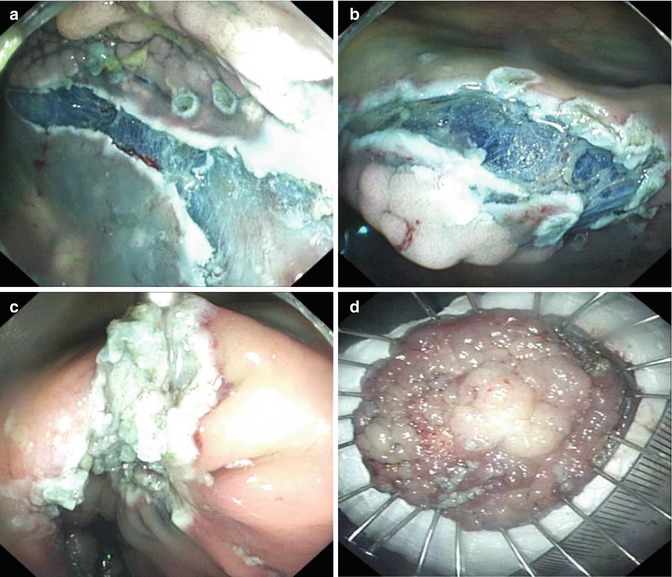

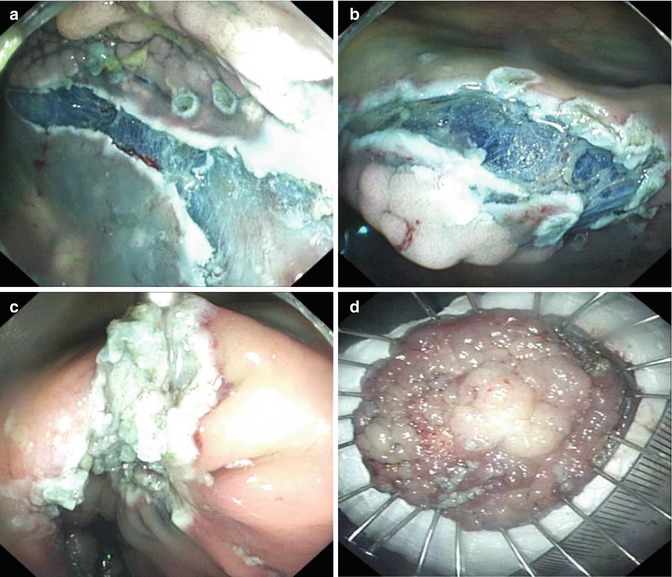

Fig. 4.14

ESD procedure for a lesion at the EGJ using a hook knife and hybrid knife. (a) Submucosal injection for uplifting the lesion at the EGJ. (b) A circumferential mucosal incision at the periphery of the marking dots was performed with a hook knife. (c) Very rich submucosal vessels. (d) Dissection of the lesion with a hybrid knife. (e) The wound after removal of the lesion was coagulated with APC. (f) Resected specimen

For lesions at the EGJ, a small initial incision is often made with a hook knife at the antral side under direct view for insertion of the tip of the IT knife into the submucosal layer. Then a circumferential mucosal incision is made from the anal side of the lesion using the IT knife, with retroflex manipulation of the scope. The ceramic ball prevents perforation of the muscle layer. Submucosal dissection is then continued from the oral side of the lesion. The solution can be injected into the submucosa during dissection to raise the submucosal layer [12, 13] (Fig. 4.15).

Fig. 4.15

ESD procedure for a lesion at the EGJ using an IT knife. (a) A flat elevated lesion located at the EGJ. (b) Marks were made around the lesion with APC. (c) A small initial incision was made with a hook knife at the oral side under direct view. (d) Dissection of the lesion with an IT knife. (e) The wound after ESD. (f) Resected specimen

4.2.3.2 ESD for Lesions at the Gastric Antrum

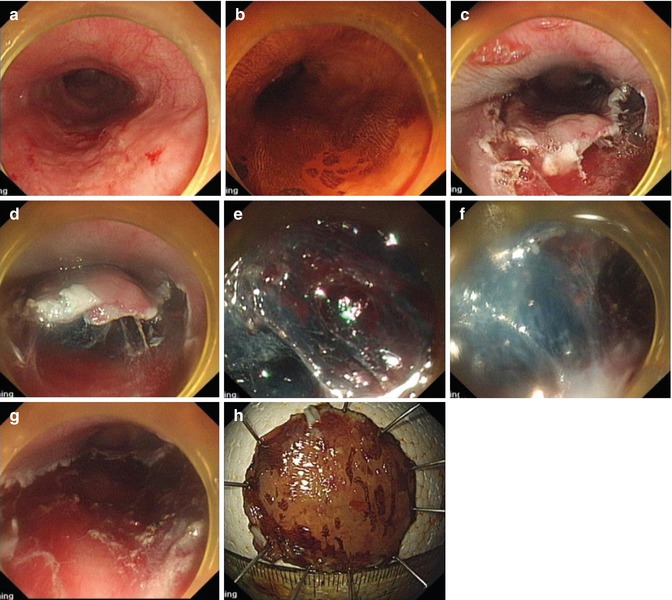

In general, the gastric antrum is regarded as an easy location for ESD due to its thick wall, large space, hence with more operating space. Thus, the beginners often start ESD training from this location. Posterior wall of the antrum more difficult than the anterior wall, and the lesser curvature side more difficult than the greater curvature because of gravitational effect of fluid cushion. Changing body position is sometimes necessary for separating lesions from the liquid. Submucosal vascular bed at the antrum is also rich, so it is particularly important to prevent and stop bleeding quickly (Fig. 4.16).

Fig. 4.16

ESD for a lesion at the gastric antrum. (a) A ulcerative lesion at the gastric antrum. (b) Identifying the margin after indigo carmine staining. (c) Marking and precutting. (d) Submucosal dissection. (e) The wound after removal of the lesion. (f) Resected specimen

Lesions located in the pyloric area are difficult to resect; ESD is technically difficult and should be carried out by experienced endoscopist. If the pre-pyloric tumor extended to the pyloric channel, ESD using scope retroflexion is often then attempted within the duodenum to evaluate tumor extension and resect the lesion from the pyloric area to the duodenal bulb [14–16]. Retroflexion in the duodenum is done in the same manner as is done in rectum. However, retroflexion may not be possible in the case of bulb deformity or duodenal ulcer. After endoscopic evaluation of pyloric lesion, marking is performed at the pre-pyloric antrum and the duodenal bulb with the endoscope retroflexed in the duodenum; then, precutting in the antral and duodenal sides is done. Subsequently, dissection using conventional and in retroflexed position and is carried out (Fig. 4.17).

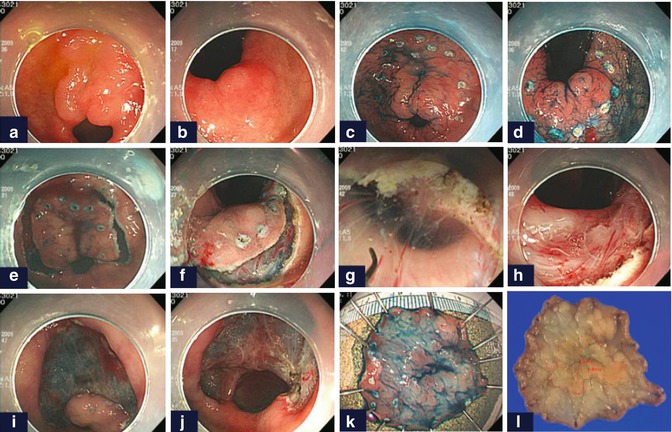

Fig. 4.17

Example of ESD using retroflexion in the duodenum. EGC was overlying on the pyloric ring (a, b). After marking of the resection margin (c, d), precutting in the antral (e) and duodenal sides (f) was done. Then, dissection using retroflexion (g, h) and conventionally (i, j) was performed. Resected (k) and the final mapping specimen (l) are shown (Reproduced with permission from Lim et al. [14])

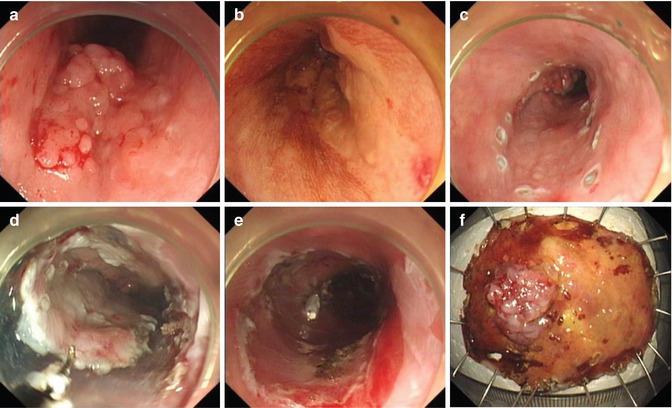

4.2.3.3 ESD for Lesions at the Gastric Angle

The gastric wall at the angle is very thin and the clear view of the angle is usually possible after adequate insufflation during gastroscopy. Because the gastric angle includes the antral and gastric body side, we pay close attention to the direction of the knife tip and cut tangentially to the submucosal layer to prevent perforation, especially when the lesion locates at the notch. The lesion also can be resected using forward view technique when it is located anteriorly at the lesser curve (Figs. 4.18 and 4.19).

Fig. 4.18

ESD for a lesion at the gastric angle using retroflexion. (a) An irregular erosion at the gastric angle. (b) Circumferential precutting. (c) Dissection of the lesion using retroflexionat the body side. (d) Coagulation of the bleeding point by APC. (e) The wound after the removal of the lesion. (f) Resected specimen

Fig. 4.19

Example of ESD for a high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia at the gastric angle. (a) An erosion at the gastric angle. (b) Making. (c) Dissection after circumferential precutting. (d) Wound after removal of the lesion. (e) Wound at the 1-week follow-up endoscopy. (f) Healing of the wound at the 3-month follow-up endoscopy

4.2.3.4 ESD for Lesions at the Gastric Body

In view of large operating space and clear view, the gastric body is also regarded relatively easy location for ESD. The forward and retroflexion view can be used and switched at any time to facilitate the resection (Figs. 4.20 and 4.21). The lesion at the lesser curve and proximal side are technically difficult to resect.

Fig. 4.20

ESD for a lesion at the gastric body using retroflexion. (a) An irregular erosion at the lesser curvature of the gastric body. (b) Identifying the margin after indigo carmine staining. (c) Making and submucosal injection. (d) Dissection after circumferential precutting in retroflexed position. (e) The artificial wound after removal of the lesion. (f) Resected specimen

Fig. 4.21

ESD for a lesion at the gastric body under the forward view. (a) A lesion at the posterior wall of the gastric body. (b) Identifying the border of the lesion after indigo carmine staining. (c) Precutting using a hook knife. (d) Dissection of the lesion using an IT knife under the forward view. (e) The wound after tumor dissection. (f) Resected specimen

4.2.3.5 ESD for Lesions with Ulcer Scar

In the past it was difficult to resect ulcerated gastric lesions or recurrent EGC after EMR by conventional endoscopic resection techniques because submucosal fibrosis preventing adequate lifting of the mucosal lesion with submucosal injection. ESD allows the removal of such lesions because the submucosal layer can be dissected under direct view. If the tissue did not lift during or after submucosal injection, the ulcerated tissues can be carefully dissected along the plane of the submucosa using a hook or IT knife (Figs. 4.22 and 4.23). The key to avoid perforation is to hold the endoscope stably and dissect the lesion along the base of scar using a tangential movement.

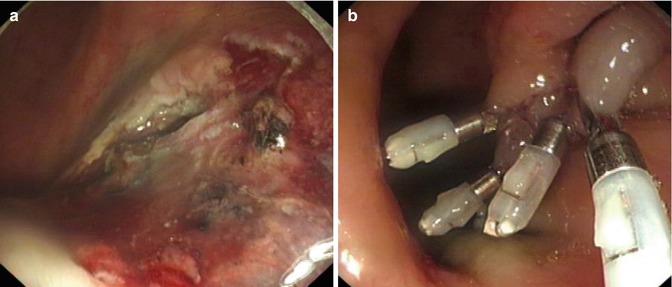

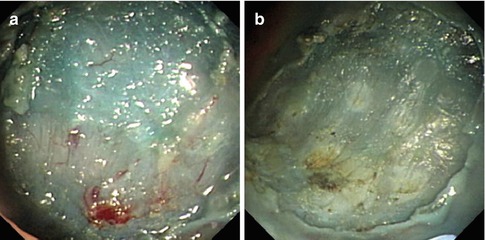

Fig. 4.22

ESD for an ulcerated lesion at the gastric body using and IT knife. (a, b) A lesion with ulcer scare (clips due to repeated biopsies and location). (c, d) Marking and injecting around the lesion. (e–g) Severe fibrosis of submucosal layer was seen and the ulcerated tissue was carefully dissected along the surface of the muscular layer using an IT knife with a tangential movement. (h) Wound after dissection

Fig. 4.23

ESD for ulcerated gastric lesion using a hook knife. (a) Sever fibrosis of submucosa layer was seen and the ulcerated tissues were carefully dissected using a hook knife. (b) The muscle layer damage was clipped

4.2.4 Postoperative Management and Follow-up

PPI prescribed for 8 weeks after ESD. Follow up examination is scheduled at 1 month to evaluate and confirm complete resection or to carry out additional treatment according to endoscopic assessment or the histology result. Patients are followed up and underwent serial endoscopy at 3, 6, and 12 monthly and annually thereafter to check for wound healing and recurrence (Fig. 4.24). Local mucosal recurrence after ESD for tumors fulfilling the indication criteria are treated by further ESD or surgical treatment (Fig. 4.25).

Fig. 4.24

Process of wound healing after ESD for a lesion at the gastric angle. (a) Three days after ESD. (b) One week after ESD. (c) Three months after ESD

Fig. 4.25

Pyloric obstruction caused by granulation tissue hyperplasia after ESD. (a) Twelve months after ESD. (b) Twenty-three months after ESD

4.3 ESD for Colorectal Lesions

4.3.1 Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most diagnosed cancer and the fourth most common cause of cancer related death worldwide [17]. In China, the mortality of colorectal cancer has increased in recent years and it has become the third common cause of cancer related death [18]. Like all cancers, early diagnosis and treatment are the key factors to improve survival. Since most colorectal cancers develop from adenomatous polyps, endoscopy screening is essential for early diagnosis. With advancement in interventional endoscopy there is an increasing trend to resect colorectal polyp and early colorectal cancer endoscopically. Endoscopic treatment is minimally invasive that offers certain advantages including faster recovery, shorter hospital stay, low cost and better postoperative quality of life compared with traditional intestinal surgery.

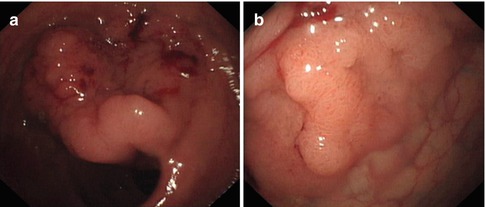

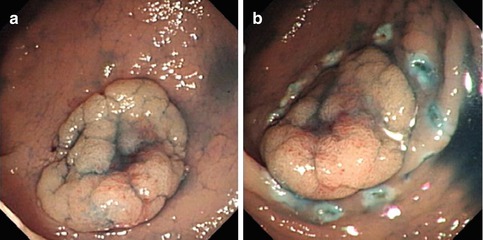

Colorectal polyps are classified by Paris classification; pedunculated polyp 0-Ip, sessile polyp 0-Is, flat polyp 0-IIb, superficial elevated with central depression 0-IIa + IIc and excavated polyp 0-IIc. Large flat type polyps are also labelled as laterally spreading tumor (LST) (Fig. 4.26). Risk of cancer is higher in sessile polyps compared with pedunculated ones. Traditional polypectomy of sessile polyp can be difficult, carries risk of complications and complete clearance of polyp at time may not be achievable.

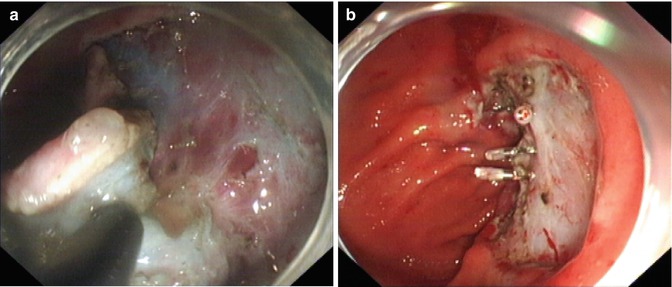

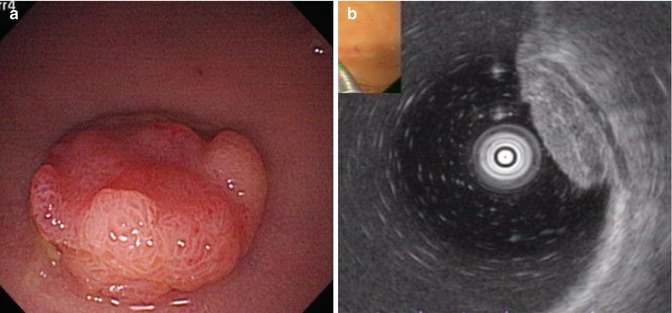

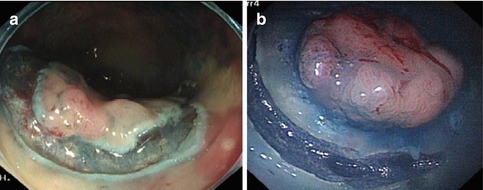

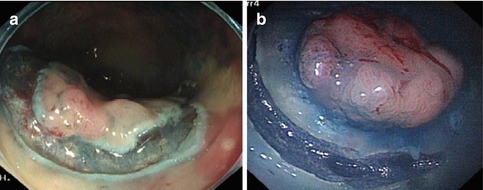

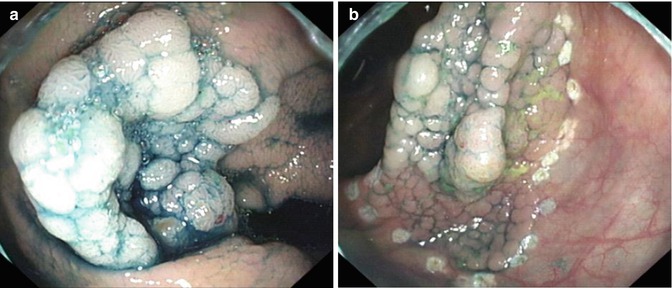

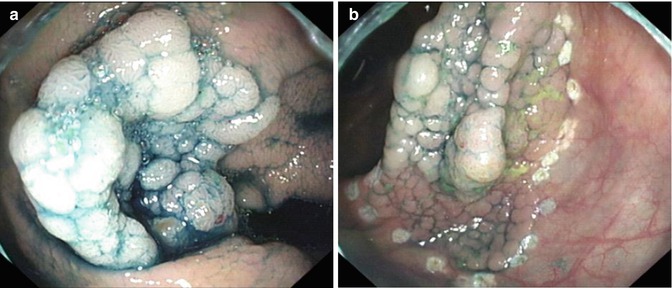

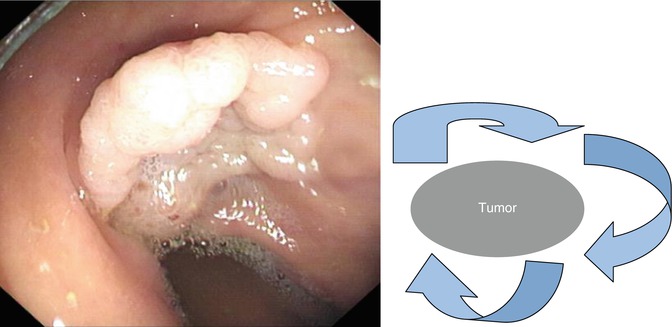

Fig. 4.26

Huge LST (5 × 6 cm, occupying 1/2 circle of enteric lumen). (a) Lateral view; (b) Anterior view

Whilst EMR could achieve complete resection for most of colorectal sessile polyps, for large flat type polyps (>2 cm), en bloc resection is usually not possible resulting in piecemeal resection. There is increased risk of recurrence and residual tumor in piecemeal resection and furthermore, accurate pathological orientation and staging becomes difficult as resected specimen is in many pieces. Pathological staging becomes even more important in the case of malignant polyps to ensure resection is complete.

In recent years, ESD technique has been used for en bloc resection of flat lesions. ESD is minimally invasive and allows to obtain complete pathology specimen for diagnosis and reduces risk of local recurrence. ESD technique was first used to resect early gastric cancer. In the last decade considerable expertise has been achieved in ESD technique that now is widely used to resect mucosal and submucosal lesions. The application of ESD in colorectal lesions started recently. Compared with the gastric wall, the colorectal wall is thinner and softer, mobile with sharp bends, hence colorectal ESD is rather difficult. Endoscopist reluctance to take up this technique was due its technical difficulty and increased risk of complications.

En bloc resection success rate of ESD for colorectal lesions in recent literature is reported at 96 % and complete resection rate of 88 % [19]. Bleeding (2 %) and perforation (4 %) remain main complication and 1 % of patient required additional surgery [19].

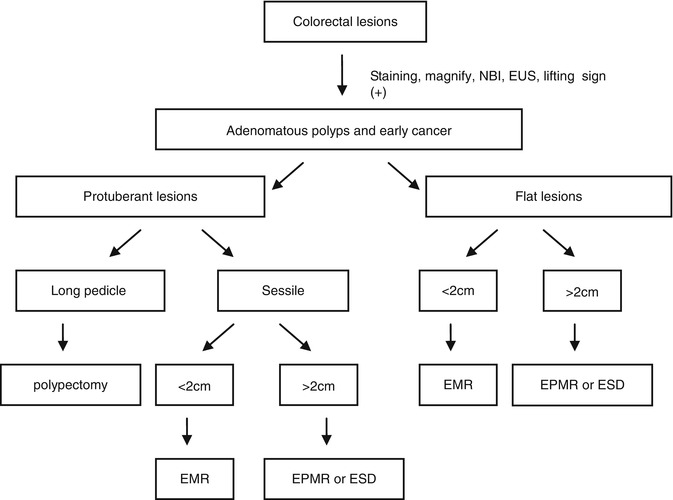

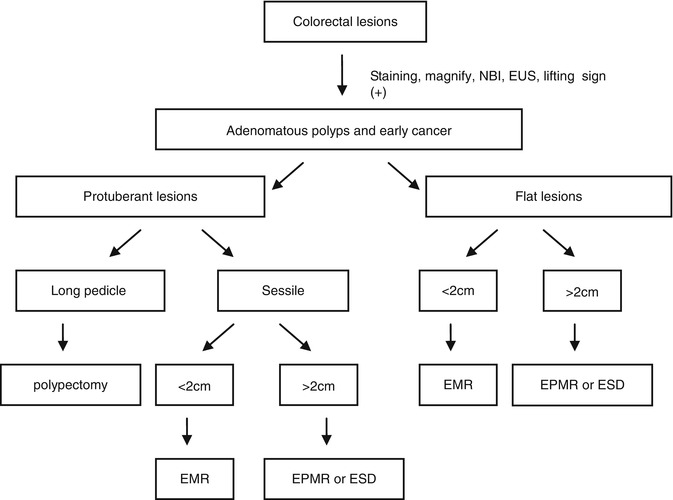

Endoscopy center of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University carries out a large numbers of ESD treatment for colorectal adenomatous polyps and early cancer. Perforation rate in our center in around 4 %. Figure 4.27 is the flow diagram of endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of colorectal lesions in our center.

Fig. 4.27

The endoscopic treatment method of colorectal adenomatous polyps and early cancer

4.3.2 The Characteristics of ESD for Colorectal Cancer

Compared with gastric ESD, the characteristics of colorectal ESD are listed as follow:

Advantages:

1.

Compared with other organs, colorectal mucosa is thinner and easier to be incised. Its submucosa is also easy to dissect. Compared with stomach, blood vessels in colonic submucosa are less prominent and bleeding easy to control. Meanwhile, changing gravity through changing patients’ position is a huge advantage to improve operating views.

2.

Mild sedation is required to carry out colorectal ESD.

Disadvantages:

1.

The colorectal wall is thin; constantly moving. Peristalsis can change the access to the lesion site, sharp bends can further limit the access and makes colorectal ESD difficult with higher complication rate when compared gastric ESD. Perforation in colorectal procedure leads to serious peritonitis because of fecal matter in the lumen, hence early surgery is recommended if perforation cannot be closed endoscopically.

4.3.3 Training

Colorectal ESD needs more robust structured training as it is difficult technique that carries high risk of complications. Before receiving the training of colorectal ESD, the operator should meet the following requirements:

1.

Being able to perform colonoscopy skillfully (>1,000);

2.

Familiar with chromoendoscopy/magnifying endoscopy to determine the range and depth of lesions;

Generally, ESD training should involve following phases: learning, observing, being assistants, practicing in animal experiments and operating.

1.

Learning phase

Learning related knowledge about colorectal ESD and being able to finish the preoperative diagnostic examination for ESD (chromoendoscopy/magnifying endoscopy)

2.

Observing phase

Learning the use of all kinds of knives, the setting of high frequency electric coagulation and electricity cut, local submucosal injection technology. Watching at least ten colorectal ESD.

3.

Assistant phase

Being familiar with the preparation of endoscopy and various accessories; Understanding the whole procedure of ESD; Assisting at least ten colorectal ESD.

4.

Animal experiments phase

Practicing repeatedly until mastering the whole procedure of ESD

5.

Operating phase [21]

The first 30 ESD procedures should be performed following the guidance of expert trainer. Start with gastric ESD. Completing 30 cases before become independent operator; Completing 50 cases treatment of gastric ESD before starting colorectal ESD treatment, which should be begun from the low rectal lesions. The trainee should carry out at least 30 colorectal ESD under guidance before operating independently.

When practicing colorectal ESD, endoscopists should begin with small lesions in rectum after accumulating enough experience of stomach and esophagus ESD. Even if dissection cannot completed, the lesion can be resected using snare after dissecting partly as long as the size of lesion matches the snare.

4.3.4 Indications and Contraindications of ESD for Colorectal Cancer

4.3.4.1 Definitions

1.

Early colorectal cancer: Early colorectal cancer is limited to the mucosa and submucosa, regardless of its size.

2.

Pre-cancerous lesions: including adenoma, adenomatosis, inflammatory bowel disease related dysplasia lesion and aberrant crypt foci (ACF) with; atypical hyperplasia.

3.

Colorectal mucosal pit (pit-pattern): Five types; Type I: Normal mucosa; Type II: Inflammatory lesions or hyperplastic polyps; Type IIIs/111L: dysplasia; Type IV: Villous adenoma/dysplasia; Type V: Cancer.

4.3.4.2 Indications [22]

1.

Adenomas or early colorectal cancer (>20 mm), which can’t be completely resected by EMR. The lesion should be evaluated by magnifying endoscopy or EUS preoperatively to determine whether it can be resected.

2.

Adenoma with non-lifting sign positive and early colorectal cancer.

3.

The residual or recurrent lesions after EMR (>10 mm) and the lesions which is difficult to be resected using EMR repeatedly.

4.

The low rectal lesion that can’t be confirmed whether it is a cancer through repeated biopsy.

4.3.4.3 Contraindications

Serious heart and lung disease and coagulation disorders. The patients who take anticoagulants should stop it for 5 days prior to ESD treatment. The relative contraindication is the lesion with invasion depth of more than sm1.

4.3.5 The Operation Approach of ESD for Colorectal Lesions

4.3.5.1 The Procedure and Skills of Colonic ESD

Confirming the Nature and Invasion Depth of Lesions

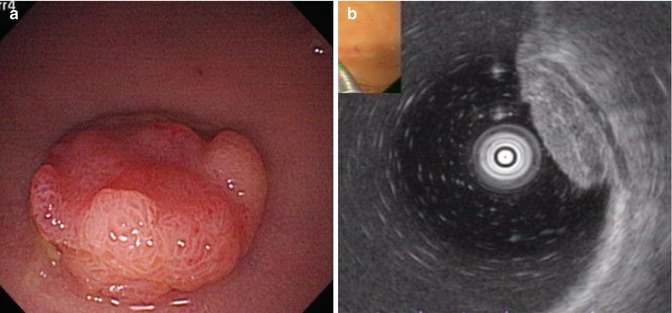

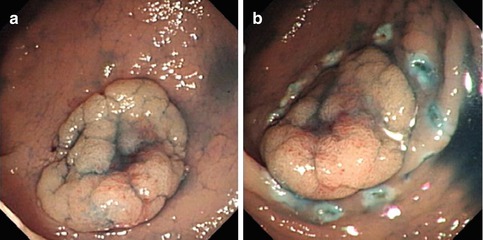

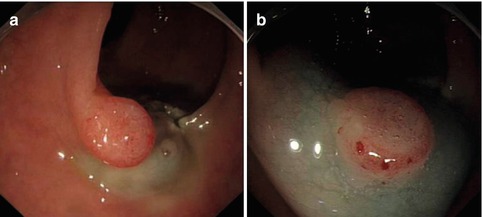

It is important to assess the lesion, its type, extent, and the possible infiltration depth of the lesion. If the lesion is suspected to be malignant, it is then essential to use NBI and magnifying endoscopy to assess possible depth. Invasive pattern are suggested by irregular and distorted crypts in a demarcated area, as is evident in Kudo’s type VN and selected cases of VI (e.g. deep submucosal invasive cancer). The following findings indicate a noninvasive pattern, regular crypts with or without a demarcated area, or irregular pits without a demarcated area, as is evident in Kudo’s type IIIs, IIIL, or IV, or selected cases of I should be subcripted (e.g., adenomatous polyps and superficial submucosal invasive cancers) [23]. Other endoscopic evaluation methods of tumor infiltration depth are, (1) air induced deformation under altered air volume is an indication for submucosa invasion (2) non–lifting sign If the lesion is not lifted by submucosa injection, it is thought to be indicative of an early colorectal cancer that has invaded the submucosa significantly, which would make surgical removal of the tumor more suitable than endoscopic resection [24]. (3) EUS can also be used to determine the depth of tumor infiltration (Fig. 4.28).

Fig. 4.28

Assessment of tumor infiltration depth before treatment. (a) A IIa + IIc lesion in the colon. (b) EUS showing lesion involved in submucosal layer

Marking

Marking dots are made by electrocoagulation at 3–5 mm from the outer border of lesions. If the border is vague, it could be determined under the guidance of NBI or indigo carmine staining (Fig. 4.29). In most colonic lesions, it is generally unnecessary to perform marking by coagulation because the extent is clearly visible.

Fig. 4.29

Marking. (a) Observing the flat lesion with staining. (b) Marking dots are made by needle-knife

Submucosal Injection

The submucosal injection solutions have been introduced in Chapter 2.4. Because the colorectal wall is thinner and softer than gastric wall, the perforation risk of ESD is much higher. The reported perforation rate is 1.4–10.4 %. There are no statistical differences regarding the location of the tumor, i.e. in the colon or in the rectum. Some revealed that perforation is associated with large tumor size (>30 mm) and the presence of fibrosis. Knife coagulation is the most common cause of perforation [25]. Submucosal injection is targeted at the proximal side of the lesion to lift it towards the field of view (Fig. 4.30). In a situation of a large exophytic lesion obscuring the view/access of the proximal side, submucosal injection can then be given at the distal edge of the lesion. In case of submucosal fibrosis, the injection can be difficult because of increase resistance. Injection may be difficult if the lesions crosses over a haustral fold. This can be over by using transparent cap on front tip of endoscope that can flatten the fold to facilitate a better view.

Fig. 4.30

Submucosal injection. (a) Injecting from proximal side to distal side; (b) lesion being lifted significantly after submucosal injection

Mucosa Incision

After adequate submucosa injection, the mucosa incision is made up to deep mucosa. Incision is either circumferential or partial (Fig. 4.31). Endocut 60 W (Effect 2) setting is used for ICC 200 generator and Endocut Q (3-1-4) for VIO200D generator. During incision, the tip of knife should be visible at all times to avoid perforation. Circumferential and partial incisions techniques have merits and demerits. In complete circumferential incision, leakage of injected fluid can easily occur. In partial incision, the dissection of the oral side is sometimes difficult because the injection fluid into the oral side of the tumor causes the position of the tumor to be perpendicular to the endoscope. In some institution, partial circumferential incision is performed for tumors size <50 mm [25]. In our center, we inject, incise and dissect sequentially. After finishing dissecting the lesion in that area, mucosa incision will be performed subsequently.

Fig. 4.31

Mucosa Incision. (a) Complete circumferential incision. (b) Partial incision

In case of bleeding during incision, endoscopists should locate bleeding vessel and perform hemostasis using knife or hemostasis forceps.

Dissection

Submucosa dissection is performed immediately after incision. Endocut 60 W, effect 2 and Forced coagulation 50 W setting in ICC200 generator or Endocut, effect 3, duration 1, interval 4 and forced coagulation, Output 50 W, effect 2 setting is used in VIO200D generator. During dissection, the knife is close to the inner side of the incision margin (tumor side). After finishing dissection a certain range of area, more mucosal incision is made. During further dissection, the transparent cap on the tip of endoscope is used to stretch submucosal space to obtain good views and facilitate dissection (Fig. 4.32). We strongly recommend to use transparent cap. Once the mucosal incision made and dissection started, injected fluid tend to leak out resulting in reduction of fluid cushion, hence endoscopist needs to be fast and skilful and assisted by experienced nurse assistant. After finishing a certain extent of dissection, gravity can be used to roll up the tumor through position changing in order to facilitate further dissection. Dissection could be performed along the tangential direction of lesion through dragging or rotating the scope.

Fig. 4.32

Cap-assisted dissection. (a, b) Using the transparent cap to push way the dissected mucosa facilitating the further procedure

During dissection, bleeding from the small submucosal vessels is usually stopped with knife (forced coagulation), however for larger vessel bleeding electric coagulation is achieved with hemostasis forceps. In case of bleeding during dissection, normal saline (containing norepinephrine) is used to flush the wound. APC or hemostasis forceps is used to perform electric coagulation after identifying the bleeding points. APC is less effective in arterial hemorrhage. Metal clips are used if the above techniques failed to stop bleeding. We try and avoid clip usage early in the procedure, as it may pose difficulties in the subsequent procedure.

In case of perforation during ESD, the suture technique and managements are discussed in detail in Sect. 5.3.

Wound Management

Small vessels or the bleeding points in the base and margins of wound, are coagulated using hemostasis forceps or APC to prevent postoperative bleeding (Fig. 4.33). If a deep muscular layer injury is identified, metallic clips are used to seal it to prevent perforation (Fig. 4.34).

Fig. 4.33

The management of wound after dissection. (a) The small vessels in the wound after dissection. (b) Using APC to treat small vessels

Fig. 4.34

The management of wound after dissection. (a) Deep muscular layer injury occurred during dissection. (b) The muscular injury was closed by metallic clips

Histological Management of Resected Specimen

The resected specimen is flattened and fixed using fine needles, size is measured before it is immersed in 4 % formaldehyde (Fig. 4.35). Continuous parallel slicing every 2 mm is carried out for detailed pathological examination to confirm the depth of invasion, lymphatic infiltration and whether the basal and lateral margins of lesion is free of tumor invasion. The pathology report should describe the gross morphology, site, size, histological type and depth of invasion. Results of pathological diagnosis, dictates whether additional surgery is required.

Fig. 4.35

The management of specimen after ESD. (a) Fixing the specimen on the flat cork using fine needle. (b) Measuring the size of lesions

4.3.5.2 The Operating Approach of ESD for Low Rectal Lesions

Introduction

Rectum is located in pelvic cavity and it is anatomically distinct. Lower rectum is extraperitoneal, connects with anal canal and is wrapped in various muscles, ligaments and fascia. Its intestinal wall is relatively thick and with fixed position with no haustrul fold, bends or peristalsis. On the other hand, it is connected with anal canal. Hence endoscopist should pay attention to this when plan to resect lesion from lower rectum. For the rectal adenomatous lesions and other benign lesions with size >2 cm including large LST or low rectal early cancer which doesn’t infiltrate into submucosa, traditional surgery carries risk of morbidity. Surgery may result in poor anal functions (reservoir function and defecation function) and sexual dysfunction. Furthermore, there is risk of postoperative complications leading to increased length of hospital stay, thus increasing procedure cost and reducing quality of life. In recent years, with the development of advanced endoscopic treatment such as EMR and ESD, most of these rectal lesions can be resected endoscopically.

Distinctive Features of Low Rectal ESD

The operating steps and skills of ESD for low rectal lesions are basically the same as colonic lesions ESD (Fig. 4.36). Low rectal lesions ESD are technically easy to resect and complications including bleeding, easy to control. However, para-rectal space and the whole posterior peritoneal space are mutually connected as a whole. In case of injury to muscular layer during ESD, high-pressure air in the lumen may enter the posterior peritoneum space resulting in posterior peritoneal emphysema, mediastinal emphysema, pneumothorax, scrotal emphysema or subcutaneous emphysema. Lesions located in anal canal are challenging to deal with because of proximity to hemorrhoid, painful squamo-columnar junction (dentate line) and anal sphincter.

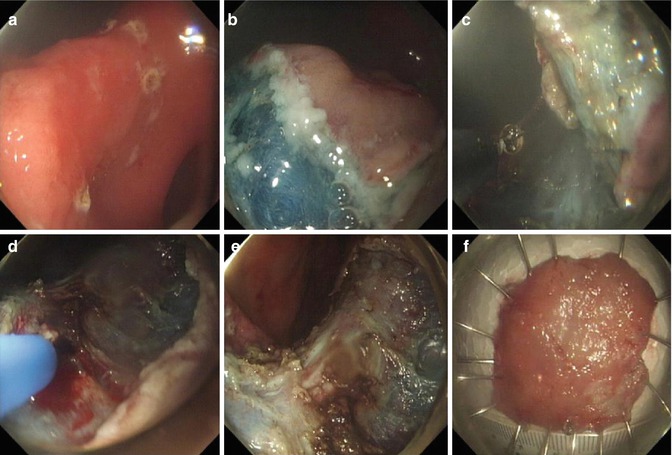

Fig. 4.36

ESD for huge LST in low rectum (retroflex view). (a) A huge LST near the dentate line. (b) Showing dissection in submucosal layer. (c) Using the transparent cap to push away the mocosa and continue dissection. (d, e) The wound after dissection. (f) Clipping the wound using metallic clips

We prefer to use of gastroscope for rectal lesion, due to its flexibility and shorter tip that allows very much needed retroflexion to facilitate resection.

Incision: Ideally incision should be made from the oral side of lesions. If it is difficult to observe the whole lesion through endoscope, especially the oral side of lesion, retroflex view could be used. However, if the view is limited or the lesion is located at closer to anal canal, mucosa incision could be performed from the anal side. Transparent cap not only allows to lift mucosal flap from submucosa for safe dissection, but also help to extend the incision margin. This allows pushing the lesion from anal canal to rectum, which makes further dissection easier.

Dissection: Hemorrhoid venous plexus between anal canal and the lower rectum, and submucosal vessels are sufficient to cause bleeding during dissection. Considering the special anatomical position of low rectum, over coagulation is rather safe in lower rectum. We recommend higher setting of forced coagulation (60–80 W) using ICC 200 generator. Brisk bleeding should be stopped with Hemostasis forceps and or metal clips. If these measures fail, then we recommend to take the scope out and apply pressure using gauze or cotton ball pressed with finger. This technique almost always stops the bleeding. This allows time to go back with endoscope and coagulate the bleeding vessels to prevent recurrence of bleeding. During dissection we recommend retroflexion of scope or rolling up the dissected tumor in order to progress in further dissection.

Wound management: After dissection low rectal lesions, electrocoagulation of bleeding points should be done using hemostasis forceps or APC to prevent postoperative bleeding. Any laceration or deeper damage to muscular layer during ESD should be closed with metal clips (Fig. 4.36).

Fig. 4.37

Different body positions in ESD treatment. (a) Right lateral position. (b) Left lateral position

4.3.6 The Application of Body Positions in Colorectal ESD

According to the anatomical features of colorectum, the intestine is flexible and not fixed, especially mesentery of sigmoid and transverse colon resulting in sharp bend and angling into close proximity to peritoneal space. Changing body positions using gravity, during colonic ESD treatment, is very useful to change shape of bowel lumen. In most cases, the change of positions may allow the lesions away from gravity. Any dissected part of the lesion will hang down due to gravitational pull resulting in stretching of submucosal tissue enough to enable easy and safe dissection [26].

In most cases, without reaching cecum, it is difficult to judge the extent of loop and flexion of colon and predict effect of position change on relative location of lesion. We recommended that a complete colonoscopy should be performed before ESD treatment with an aim to reduce the loops to straighten the scope. The body positions during colorectal ESD could be left lateral position, supine position and right lateral position. Changing position could not only change the relative position between lesions and endoscope, but also help to find the most ideal position for ESD, and allow ESD to be performed from various directions. Endoscopists should assess effect of position on lesion access and take into account all factors including effect of gravity, lesions location, the shape and status of enteric lumen and whether the position of endoscope facilitate the knife to incise and resect easily.

Here is a case to explain how to change in position of patient helps during colorectal ESD treatment.

There is a 45-year-old male patient with a nodular mixed type LST of 4 cm diameter in hepatic flexure of colon. Photograph of lesion at the right lateral position and the left lateral position shown in Figs. 4.37 and 4.38 shows determination of position of lesion during ESD (Fig. 4.39).

Fig. 4.38

The determination of position during ESD

Fig. 4.39

Position chosen during ESD treatment. (a) The lesion is hard to be dissected in right lateral position. (b) Most of the lesion is dissected in the left lateral position. (c) The wound of ESD. (d) The resected specimen size is 5.0 × 4.5cm

4.4 ESD of Recurrent/Residual Lesions After Previous EMR

4.4.1 Tumor Recurrence and Residual Tumor After Previous EMR

EMR is a widely used to resect sessile and advanced mucosal neoplasia of gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 4.40). EMR is highly effective, easy to perform, requires less expertise, equipment and instruments. It is minimally invasive treatment. Patients benefit from fast recovery and reduced length of hospital stay. Despite being less invasive and effective treatment, EMR does have limitations. It can only resect lesions smaller than 2 cm. For lesions larger than 2 cm, en bloc resection is difficult to achieve. Larger lesion can be resected by EPMR (Figs. 4.41, 4.42, and 4.43), but the procedure is more difficult and time-consuming compared with EMR. The resection tends to be incomplete (Fig. 4.44). Remnant lesions (small islands or bumps) are treated by coagulation methods (i.e. argon plasma coagulation, APC), to prevent tumor recurrence (Fig. 4.45). According to the data from Japan’s National Cancer Center Hospital, the recurrence rate of standard EMR was 8.5 % (53/620) in a cohort of more than 2,000 cases since 1987 [27]. However, in one of the case series the rate of residual and recurrent tumor was reported as high as 35 % (Table 4.1).