, Liqing Yao1 and Xinyu Qin2

(1)

Endoscopy Center, Zhongshan Hospital Fudan University, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China

(2)

General surgery, Zhongshan Hospital Fudan University, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China

Abstract

Submucosal tumors (SMTs) are common in upper GI tract and appears as elevated submucosal mass with intact overlying mucosa. These submucosal lesions, mainly arise from non-epithelial mesenchymal tissue in the GI wall, including stromal tumor, leiomyoma, lipoma or vascular tumors etc. EUS examination can usually determine characteristics the lesions. Snare polypectomy by electrocautery technique is simple and can obtain accurate pathological diagnosis. But there is risk of incomplete resection, postoperative bleeding and perforation. Ligation therapy is simple for thin pedicle lesions, with low risk of hemorrhage and perforation, but lack of postoperative pathologic diagnosis.

5.1 Snare Polypectomy or Ligation Treatment of Submucosal Tumors

Submucosal tumors (SMTs) are common in upper GI tract and appears as elevated submucosal mass with intact overlying mucosa. These submucosal lesions, mainly arise from non-epithelial mesenchymal tissue in the GI wall, including stromal tumor, leiomyoma, lipoma or vascular tumors etc. EUS examination can usually determine characteristics of the lesions. Snare polypectomy by electrocautery technique is simple and can obtain accurate pathological diagnosis. But there is risk of incomplete resection, postoperative bleeding and perforation. Ligation therapy is simple for thin pedicle lesions, with low risk of hemorrhage and perforation, but with disadvantage of losing specimen.

5.1.1 Snare Resection

5.1.1.1 Indications

Digestive tract SMTs originated from the muscularis mucosa and submucosa including leiomyoma, stromal tumors, lipoma, schwannoma, carcinoid tumors, hematolymphangioma, ectopic pancreas and cyst, etc.

5.1.1.2 Equipment for Operation

The same as EMR and ESD procedures

5.1.1.3 Preoperative Evaluation

Information for patients and informed consent are similar to those of EMR and ESD. For patients with SMTs, preoperative EUS examination is taken routinely to confirm and assess the tumor. CT scan is preferred over EUS to evaluate the dominant growth pattern of the tumor. In addition, it can rule out extraluminal extension, distant metastasis for tumor, full-thickness resection of the SMT is inevitable. The patient should be warned about possibility of conversion to laparoscopic surgical resection. We routinely use Propofol sedation for endoscopic snare resection.

5.1.1.4 Operating Procedure

It is important to carefully assess the lesion. After lesion being identified, resection methods can selected.

1.

Snare polypectomy can treat SMTs originated from the muscular is mucosa or submucosa (Figs. 5.1 and 5.2). For those with thick pedicles, endoloop ligation combined with high frequency electrocautery can be attempted to reduce postoperative complications such as bleeding and perforation.

Fig. 5.1

Snare polypectomy treating a gastric SMT. (a) A gastric antral SMT. (b) EUS delineated the lesion was originated from the mucosal muscularis. (c) Direct polypectomy was performed by snare. (d) The wound after resection

Fig. 5.2

lipoma of the ileocecal valve, confirmed with direct high-frequency probe, electrocautery resection with snare

2.

EMR Small SMTs from muscularis mucosa can be resected by EMR technique (Figs. 5.3, 5.4, 5.5, and 5.6)

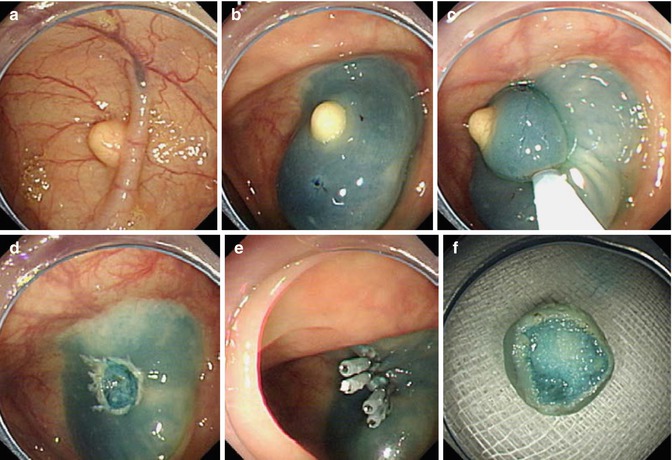

Fig. 5.3

EMR for treating a lobulated esophageal leiomyoma. (a) A lobulated leiomyoma was seen in the middle esophagus. (b) Submucosal injection was performed to elevate the lesion. (c, d) A snare with electrocautery was applied to resect the tumor. (e) The wound after resection. (f) The resected specimen

Fig. 5.4

EMR for treating a duodenum SMT. (a) A duodenal SMT. (b) A well-lifted sign was seen after submucosal injection. (c) EMR was performed successfully

Fig. 5.5

EMR of a lipoma of ascending colon originated from submucosal layer

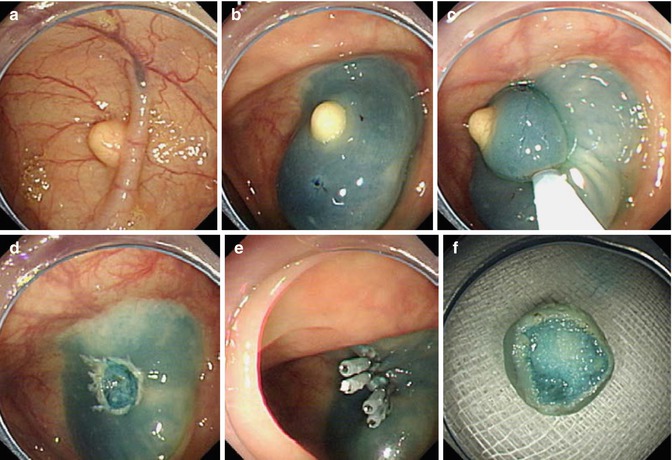

Fig. 5.6

EMR for a colonic lipoma. (a) A SMT in hepatic flexure. (b) Submucosal injection revealed a well-lifted lesion. (c) Extended resection together with the surrounding mucosa was performed. (d) The wound after resection. (e) Metallic clips to close the defect. (f) Resected specimen; postoperative pathological diagnosis was a lipoma

4.

Modified EMR with pre–cutting technique– EMR with circumferential mucosal precutting facilitates the en bloc resection and it also works for SMTs originated from muscularis mucosa (Fig. 5.7). Sometimes instead of circumferential cutting, a linear pre-cut is more helpful to enucleate the tumor [1] (Fig. 5.8).

Fig. 5.7

EMR with pre-cutting technique for esophageal leiomyoma. (a) A SMT originated from muscularis mucosa in esophagus. (b) Mucosa injection showed a well-lifted lesion. (c) Incision of mucosa longitudinally with hook knife to fully expose the tumor. (d) Resected the pre-cut lesion with snare. (e) Wound after hemostasis. (f) Resected specimen

Fig. 5.8

Enucleation of an esophageal SMT. (a) an esophageal SMT was found. (b) Per-cutting the mucosa after submucosa injection. (c) The lesion was enucleated beneath the mucosa. (d) The covering mucosa was intact. (e) Sealing the incision wound with metallic clips. (f) The resected lesion was a lipoma

Caution EUS can underestimate the depth of SMTs particularly near cardia, lesion that appear to be originating from muscularis mucosa are in fact rooted from deep layers or even extending exluminally (Fig. 5.9). Timely termination of the procedure, if the endoscopist is not skillful in closing the full-thickness defect, should be considered.

Fig. 5.9

Incomplete piecemeal resection for leiomyoma in lower esophagus near cardia for the lesion rooting in very deep layers

5.

For cystic lesion originated from the submucosal layer, puncture or fenestration can be used to aspirate the top mucosa of the cyst (Fig. 5.10). Complete resection of the cyst wall can avoid recurrence.

Fig. 5.10

Puncture of an esophageal cyst. (a) An esophageal cyst. (b) EUS revealed an echoless lesion (c) An injection needle was puncture into the cyst. (d) Pale yellowish cyst fluid was drained from the cyst

5.1.1.5 Complications

Bleeding is a common complication. Minor bleeding can be stopped by APC, but active artery bleeding need to be coagulated by hemostasis forceps. Perforation is also a serious complication. Intraoperative perforation may immediately closed with metallic clips. Clips can seal most of the perforations, if it fails, early salvage laparoscopic surgery is needed. Perforation identified afterwards can lead to plural and abdominal infection, and often require open surgery (Fig. 5.11).

Fig. 5.11

Perforation after ileocecal SMT snare resection. (a, b) A massive ileocecal SMT was found on colonoscopy and confirmed on EUS. (c) Snare polypectomy was attempted for resection. (d) Perforation occurred during procedure. Immediate laparoscopy was performed to close the perforation

5.1.2 Ligation Therapy for GI SMTs

Ligation therapy for GI SMTs is developed from the band ligation treatment of esophageal varices. Principle is to block the blood supply of SMT through ligation leading to resection by local necrosis. It provides an easy method for treating SMT and reduces the risk of bleeding and perforation (Fig. 5.12). However, ligation for large tumors may have a risk of incomplete resection. The biggest drawback of endoloop ligation is that it cannot obtain tissue for pathological diagnosis. Nevertheless, with the help of preoperative fine needle aspiration (FNA) this may be overcome.

5.1.2.1 Indications

Although this procedure is suitable for SMT smaller than 2 cm originated from muscularis mucosa, submucosa and muscularis propria, but it is mainly used to resect SMT originated from muscularis propria.

5.1.2.2 Equipment

A band ligation device, endoloop and a transparent cap

5.1.2.3 Treatment Options

1.

Endoloop ligation: For SMT with thin root, direct ligation with endoloop can be used. The diameter of endoloop is selected according to the maximum diameter of the head of lesions. An endoloop is placed around the lesion with a hood attached to the endoscope over the lesion, then maximum sustained suction is applied while the endoloop is tightened at the base of the lesion (Fig. 5.12).

Fig. 5.12

Endoloop ligation for a SMT in gastric fundus. (a) SMT in the gastric fundus. (b) EUS confirmed the lesion was in superficial layers. (c) A transparent hood was attached to the scope. (d) Endoloop was deployed at the lesion stalk

2.

Rubber band ligation: The lesion is aspirated into the transparent cap of the band ligator device, followed by deployment of an elastic rubber band which results in ischemic necrosis of the tumor.

3.

Ligation through dual–channel endoscope: This method can be used in larger SMTs (~3.0 cm in diameter). First, place the snare through one tunnel, draw SMTs completely into the snare using suction, and tighten the snare until mucosa color turning into dark purple. Then place endoloop ligator through the other channel, and adjust its position to make the endoloop fully fit into the base of the lesions, tighten it and push the slider until the loop is detached (Fig. 5.13). Settle the snare out it to the opposite direction and withdraw the snare. Sometimes, it may cause the endoloop and snare intertwined, or may lead to perforation for excessive pulling of the snare.

Fig. 5.13

Endoloop ligation with duel-channel endoscope (arrow showing the snare through one channel, and the endoloop through another channel)

For treating protruded SMTs with long stalk, we prefer placing the endoloop through one channel first, and place biopsy forceps through the other to facilitate ligation at the base to prevent postoperative bleeding of the residual base. Finally, the lesion is resected by a snare over the endoloop [2] (Fig. 5.14).

Fig. 5.14

Ligation treatment for a gastric lesion through dual-channel endoscope. (a) A protruded lesion in stomach. (b) An endoloop is deployed with the assistance of a biopsy forceps. (c) Snare polypectomy is performed over the ligation. (d) Resected specimen

4.

Endoloop ligation assisted with partial ESD

This method is suitable for lesions larger than 3.0 cm in diameter or tumors originated from muscularis propria. ESD is performed first, then ligate the lesion with endoloop after partially dissected from the submucosal layer. It can effectively avoid perforation and ensure the endoloop is placed at the base, thus preventing falling off of the loop. If perforation occurs during dissection, operators can suck the lesion together with the perforation site into the cap, then ligate them by endoloop which can achieve the effect of both ligation and perforation repair. It has advantages in treating lesions originated from muscularis propria (Fig. 5.15)

Fig. 5.15

Endoloop ligation during ESD procedure. (a) A small perforation in the process of ESD (arrow). (b) Suck the lesion and the perforation site into the cap. (c) Endoloop successfully deployed, achieving both ligation treatment and perforation repair

5.

Caution for ligation treatment

For SMTs smaller then 1.3 cm [3], we advise to use rubber band ligation as it offers sustained ligation and block the blood supply completely and achieve curative resection. Some SMTs may fall off incompletely by incomplete block of blood supply by endoloop ligation, as endoloop cannot produce sustained contraction. A regular follow-up examination should be scheduled after ligation. Repeated ligation can be done if necessary. Tumor often falls off 5–7 days after ligation. Complications such as bleeding and perforation are uncommon, however, the risk still exists. Repeat examination is required to ensure complete resection (Fig. 5.16).

Fig. 5.16

Residual tumor after endoloop ligation for gastric SMT. (a) A gastric SMT found in the fundus (arrow). (b) EUS confirmation. (c) Endoloop ligation treatment was performed for the lesion. (d) Follow-up exam showing no ‘residual’ 1 year after the procedure. (e) On 5-year follow-up exam EUS showing a similar lesion at the same site. (f) Subsequent endoscopy confirmed recurrence likely from residual tumor (arrow)

5.2 Endoscopic Submucosal Excavation (ESE)

Endoscopic resection and endoloop ligation have been widely used to resect mucosal GI tumors, but unsuitable to resect submucosal tumors (SMTs) completely. Endoloop ligation has a further disadvantage as tumor can’t be retrieved for pathological assessment. Laparoscopic or thoracoscopic resection is also considered minimally invasive treatment for GI SMTs, but location of the lesion can be difficult. Furthermore, the linear stapler may cause excessive resection that may result in stricture formation. With the improvement in ESD expertise, most of GI tract lesions can resected en bloc and perforation dealt with endoscopically. Standard ESD knives are used. We use the term endoscopic submucosal excavation (ESE) for resecting SMTs located beyond submucosal layer, i.e. mainly in the muscularis propria.

5.2.1 Preoperative Evaluation

EUS can provide useful information that help decide the endoscopic treatment. SMTs originating from deep layers (beyond muscularis propria) can be treated by ESE or even full-thickness resection, but mucosal and most submucosal lesions can be resected by EMR/ESD technique. Submucosal injection can be useful to determine lesion origin. If it can be lifted by submucosal injection, the lesion is superficial, otherwise, it arises from deep layers thus requiring ESE. CT scan can differentiate submucosal lesion from extrinsic compression (Fig. 5.17).

Fig. 5.17

Extraluminal compression mimicking a gastric SMT. (a) A gastric SMT was diagnosed by referral hospital, EUS confirmed it. (b) Endoscopic treatment was attempted. The marking dots were displaced during procedure, indicating the “lesion” was actually extraluminal compression

5.2.2 ESE Procedures

ESE for SMTs originating from the muscularis propria is similar to ESD procedure.

Due to the deep location of tumors, it is a challenging endoscopic procedure hence only to be carried out by expert endoscopist. Larger SMTs (>3 cm) should be resected by SME technique in collaboration with surgical team. If complications such as perforation or massive bleeding cannot be dealt with endoscopically, it may be necessary to convert to surgery.

5.2.3 Marking

For intraluminal large (>3 cm) SMT, it is not necessary to mark lesions before ESE. For small and deep lesions (<1 cm), marking is recommended to avoid losing them after submucosal injection (Fig. 5.18).

Fig. 5.18

Marking of different lesions by APC probes

5.2.4 Submucosal Injection

Saline mixture is used for injection. Main purpose of submucosal cushion is to provide space for submucosa dissection and to avoid perforation (Fig. 5.19).

Fig. 5.19

Multiple submucosal injections were done beneath the marking dots

5.2.5 Mucosal Incision

The mucosa is incised outside the marker dots with an ESD knife. Some superficial submucosal lesions can be exposed after mucosa incision (Fig. 5.20). Be careful to avoid cutting too deep for gastric fundal lesions, as the wall of fundus is thin and a single cut can cause perforation. Some deep lesions could not be easily exposed after mucosa incision, snare removal of the overlying mucosa then can expose the lesion. If this doesn’t work, the tumor may be located in deep muscular layer, cautious cutting into the muscle could then help to expose the tumor (Fig. 5.21).

Fig. 5.20

SMTs exposing (well) after mucosal incision. (a) Large esophageal SMT exposing well after mucosa incision. (b) Showing a gastric fundal leiomyoma after mucosal incision. (c) Exposing a gastric GIST after mucosal incision. (d) Rectal leiomyoma

Fig. 5.21

Resection of the superficial mucosa with snare to expose the lesion

5.2.6 Excavation

Dissect around the lesion and excavate it under direct visualization after further submucosal injection to seperate submucosal layer from muscle layer. If it is difficult to excavate deeper lesions or lesions protruding into serosa, further dissection can be facilitated using combination of different knives. If the endoscopic view is suboptimal, switching to dual channel scope for passage of forceps to apply traction facilitate dissection and excavation of tumors.

5.2.7 Case Illustrations

If it is difficult to incise the proximal mucosa of lower esophageal SMTs, the tumors can be pushed into gastric cavity after partially dissection, then use ESD knives to dissect in the stomach (Figs. 5.22, 5.23, 5.24, 5.25, 5.26, 5.27, 5.28, 5.29, 5.30, and 5.31).

Fig. 5.22

ESE for an esophageal SMT. (a) An irregular SMT was found in the upper esophagus. (b) Submucosal injection. (c) Revealing the SMT after mucosa incision. (d) Further dissection of the tumor. (e) Finishing dissection and sealing the mucosa. (f) Resected specimen (2.0 cm * 7.0 cm)

Fig. 5.23

ESE for a large horseshoe-shaped SMT close to the cardia. (a) Large horseshoe-shaped SMT closed to the cardia. (b, c) Mucosa incision and resection. (d, e) Push it to the gastric lumen and excavate the lesion. (f) The wound after resection. (g) The resected tumor. (h) Two-month follow up endoscopy showing a nice healed wound

Fig. 5.24

ESE for a SMT in the cardia. (a) SMT in the gastric cardia. (b) Submucosal injection. (c) A linear incision was made. (d, e) Dissect the tumor in retroflexed view. (f) The wound. (g) The resected specimen

Fig. 5.25

ESE for a worm-like leiomyoma in the cardia. (a) A SMT in the cardia. (b) Dissect on retroverted view. (c) The root of the tumor originating from lower esophagus. (d) The resected specimen

Fig. 5.26

ESE for a gastric SMT. (a) A SMT at upper gastric body. (b) Submucosal injection. (c) Mucosa incision. (d) Dissection. (e) The wound. (f) The resected specimen (3.5 cm * 3.0 cm)

Fig. 5.27

ESE for a SMT in gastric fundus. (a) A SMT in the gastric fundus. (b, c) After mucosa incision, carefully dissect the tumor from the muscular layer (arrow showing the muscular layer). (d, e) closing the wound with metallic clips. (f) The resected tumor

Fig. 5.28

ESE of an irregular lobulated leiomyoma in gastric body. (a) An irregular-shaped SMT in upper gastric body. (b) Revealing the SMT after resection of the overlying mucosa. (c, d) Dissection of the SMT from the muscular layer with caution to keep the capsule complete. (e) Wound after dissection. (f) The resected tumor

Fig. 5.29

ESE of an irregular lobulated leiomyoma in gastric body. (a) A slightly elevated SMT in gastric angle. (b) Marking the extent before submucosal injection. (c) Submucosal injection. (d) Mucosa incision. (e) Dissecting the tumor from muscular (layer) along the capsule of the tumor. (f) Arrow showing the serosa after dissection (g) metallic clips were deployed to close the muscular defect. (h) Wound after closure by clips. (i) The resected specimen

Fig. 5.30

ESE of a SMT in muscularis propria of gastric body. (a) A round-shaped SMT in gastric body. (b, c) Dissecting the tumor from muscular layer. (d) Sealing the wound with metallic clips. (e) The resected tumor. (f) Postoperative pathological diagnosis is a small round cell tumor, immunohistochemical staining confirmed it as a glomus tumor

Fig. 5.31

ESE of a rectal leiomyoma in the muscularis propria. (a) Slightly elevated submucosal tumor in the rectum was found. (b) EUS showed the lesion was in the muscularis propria. (c, d) Cutting the submucosal layer and dissecting the tumor. (e) The wound after resection. (f) Resected tumor

It is also feasible and safe to perform piecemeal resection for large irregular SMTs (Figs. 5.32 and 5.33).

Fig. 5.32

ESE of a horseshoe leiomyoma in lower esophagus. (a) A horseshoe-shaped SMT in lower esophagus. (b) Submucosal injection. (c, d) The tumor was exposed after mucosa dissection. (e) The tumor was resected in a piecemeal fashion

Fig. 5.33

Piecemeal resection of mid-esophageal leiomyoma. (a) SMT in mid-esophagus. (b) Mucosa incision. (c–e) Exposing the tumor from dissection, it was originating from the muscularis propria. (f–i) Piecemeal resection of the tumor, the white circle showing the roots of tumor. (j) Closing the remaining mucosa with metallic clips. (k) Follow-up endoscopy showing a well-healed scar

For larger tumors with obscure tumor border or endoscopic features of malignancy or excessive bleeding that is difficulty to stop, it is wise to stop the procedure and convert to surgery (Figs. 5.34, 5.35, and 5.36).

Fig. 5.34

Procedure was stopped in these cases. (a) Only muscle layer thickening was found during dissection, procedure stopped at this stage. (b) Tumor in descending duodenum, massive bleeding was encountered during procedure

Fig. 5.35

Stop excavation. (a) Slightly elevated SMT was found in gastric angle. (b, c) The tumor was found with a broad base. (d) Procedure stopped (unsuitable for endoscopic resection)

Fig. 5.36

Procedure stopped timely. (a) An esophageal SMT. (b, c) Tumor was exposed without obvious capsule. (d, e) Active bleeding occurred when needle puncture was attempted. (f) The bleeding was stooped with several clips.

5.2.8 Wound Management

Small blood vessels visible in wounds after resection should be coagulated by hemostatic forceps or APC. When the bleeding spot is too deep for APC or hemostatic forceps to grasp, metallic clips can achieve successful hemostasis (Fig. 5.37).

Fig. 5.37

Wound management. (a) Esophageal wound. (b) Gastric wound. (c) To prevent the delayed bleeding in gastric fundus, this wound was sutured by metallic clips. (d) If the dissection reaches the deep layers, we use endoloop to reinforce the suture by clips. (e) Rectal wound

5.2.9 Postoperative Treatment and Follow-up

Patients are kept nil by mouth for 1 day after procedure. We routinely use of hemocoagulase injection in all cases for 24 h along with PPI in case of gastric lesions. Clear liquids allowed if no complication occurred on day 2. Patients are followed up at 3, 6 and 12 months afterwards.

5.2.10 Prevention and Treatment of Complications

Bleeding and perforation are the major complications. Hemostasis can be achieved by contact coagulation of bleeding spots with knife or by using hemostatic forceps. If the bleeding is too brisk to identify the exact bleeding spot, flush the wound with iced saline help locate it, then hemostatic forceps is applied to stop the bleeding. Hemostatic clips can be used for brisk arterial bleeding, but this will influence dissection in the subsequent procedure (Figs. 5.38 and 5.39).

Fig. 5.38

Hemostasis by the combined use of hemostatic forceps and APC. (a) A large esophageal SMT. (b) Bleeding during excavation. (c) Active bleeding after tumor removal, successful hemostasis was achieved by the combined use of hemostatic forceps and APC. (d) The resected tumor

Fig. 5.39

Hemostasis with metallic clips. (a) A gastric SMT in the fundus. (b) Massive bleeding occurred during excavation. (c) Successful hemostasis was achieved by application of metallic clips. (d) Finish excavation of the tumor

If perforation occurred during ESE, it is safe to continue and complete en bloc endoscopic resection if the patient’s observation are satisfactory. Otherwise, piecemeal resection with snare can be attempted to reduce procedure time and ensure safety. In such difficult situation sometimes it is safer to stop the procedure prematurely with incomplete resection, but to retrieve a piece of specimen for pathological diagnosis. If the repair of perforation fails, salvage laparoscopic surgical repair is required urgently (Figs. 5.40, 5.41, 5.42, and 5.43).

Fig. 5.40

Esophageal perforation closed with metallic clips. (a) Large SMT in esophagus. (b) The tumor was originated from deep muscular layer, perforation occurred during resection. (c) Nonsurgical management with metallic clips. (d) Follow up after 3 months (arrow showed the scar)

Fig. 5.41

Suturing of perforation with metallic clips. (a) Perforation occurred during tumor resection (arrow). (b) Wound after resection. (c) Suturing the wall defect with metallic clips. (d) Follow-up endoscopy after 6 months showed well-healed wound

Fig. 5.42

Management of perforation accompanied by bleeding. (a, b) Perforation (a, arrow) occurred during tumor resection accompanied by active bleeding (b, arrow). (c, d) Suture perforation with several metallic clips and stop bleeding at the same time

Fig. 5.43

Management of perforation with OTSC system. (a) Excavation for a gastric SMT. (b) A perforation occurred during tumor resection (arrow). (c, d) An OTSC was deployed to suture the perforation. (e) It was still in position after 3 years. (f) Removal of OTSC by foreign body forceps was attempted but failed

5.3 Endoscopic Full-Thickness Resection (EFTR)

5.3.1 Introduction

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) techniques are widely used for en bloc resection of superficial GI carcinomas and premalignant lesions from mucosal and submucosal layers. However these techniques are suboptimal in resecting subepithelial tumors originating from muscularis propria (MP) layer. Limitations include an increased risk of perforation and failure to achieve R0 resection margins. Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) has the potential to overcome these limitations, although closure of the resulting wall defect can be difficult and remains the main challenge. EFTR can be laparoscopic-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection (LAEFTR) and without laparoscopic assistance. For small SMTs, some endoscopic surgeons perform LAEFTR, which uses endoscopic techniques to resected GI SMTs followed by laparoscopic suture of the wound. EFTR without laparoscopic assistance gets rid of the dependence of the laparoscopic technique.

EFTR offers an alternative option to traditional surgical resection treatment in selected patients. However, closure of wall defect remain a challenge and with availability of newer devices will help to overcome this shortcoming.

5.3.2 Indications and Contraindications

EFTR has been in clinical use in centers with advanced endoscopic expertise, but there is no consensus about indication or suitability of EFTR. EFTR allows complete resection of tumors, hence reduces the risk of residual tumor and improves accuracy of pathological diagnosis and staging. Suzuki et al. reported EFTR of rectal and duodenal carcinoids and endoscopic complete closure (ECDC) [4]. Sumiyama proposed that EFTR technique can be used to resect submucosal tumor and large laterally spreading tumor involving the submucosa or muscularis propria [5]. We propose the following as indications of EFFTR:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Absolute indication:

1.

EUS and CT evidence GI tumor arise from muscularis propria;

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree