A major paradigm shift has occurred in the management of dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (BE) and early esophageal carcinoma. Endoscopic therapy has now emerged as the standard of care for this disease entity. Endoscopic resection techniques like endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection combined with ablation techniques help achieve long-term curative success comparable with surgical outcomes, in this subgroup of patients. This article is an in-depth review of these endoscopic resection techniques, highlighting their role and value in the overall management of BE-related dysplasia and neoplasia.

Key points

- •

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are indispensable endoscopic resection (ER) interventions in patients with dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (BE) and esophageal adenocarcinoma, having diagnostic (staging) and therapeutic (curative) value.

- •

ER interventions are frequently combined with endoscopic ablation to manage dysplastic BE.

- •

For mucosal (HGD and T1a) disease, continued endoscopic management is recommended.

- •

For T1b (submucosal involvement) or higher stage, esophagectomy is still the standard of care.

- •

ER is the most accurate intervention that helps with the above stratification.

Introduction

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is characterized by a change in the lining of the esophagus from stratified squamous epithelium to a metaplastic columnar epithelium (IM) that has a low, but real, malignant potential. The progression of BE to carcinoma occurs in a stepwise fashion from IM through dysplasia (low grade to high grade [HGD]). Endoscopic surveillance is recommended for patients with BE to detect and manage dysplasia before malignant transformation. The annual risk of BE progressing to adenocarcinoma is estimated at 0.1% to 0.5%. However, this risk increases to 10% per year with HGD. Esophagectomy was conventional treatment for patients with HGD and early esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). However, this is associated with significant morbidity (and some mortality), even in high-volume centers. For this reason, endoscopic management of dysplastic BE and EAC has become extremely popular. This article focuses specifically on the role of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in patients with dysplastic BE and EAC.

Introduction

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is characterized by a change in the lining of the esophagus from stratified squamous epithelium to a metaplastic columnar epithelium (IM) that has a low, but real, malignant potential. The progression of BE to carcinoma occurs in a stepwise fashion from IM through dysplasia (low grade to high grade [HGD]). Endoscopic surveillance is recommended for patients with BE to detect and manage dysplasia before malignant transformation. The annual risk of BE progressing to adenocarcinoma is estimated at 0.1% to 0.5%. However, this risk increases to 10% per year with HGD. Esophagectomy was conventional treatment for patients with HGD and early esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). However, this is associated with significant morbidity (and some mortality), even in high-volume centers. For this reason, endoscopic management of dysplastic BE and EAC has become extremely popular. This article focuses specifically on the role of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in patients with dysplastic BE and EAC.

Endoscopic therapy of Barrett’s esophagus: paradigm shift

In recent years, a significant paradigm shift has taken place in the realm of esophageal dysplasia/early neoplasia management. The treatment of esophageal HGD and EAC has shifted from surgery (esophagectomy) to an organ-sparing, comprehensive endoscopic management approach. With the advent of endoscopic ablation technologies such as radiofrequency ablation and cryotherapy, and resection techniques like EMR and ESD, endoscopic therapy has now become the standard of care for management of dysplastic BE and EAC. Endoscopic resection (ER) not only is used for curative intent but also allows a definitive histologic diagnosis, accurate pathologic staging, and potential cure, with a minimally invasive approach. Several studies have reported the efficacy and safety of endotherapy in the management of HGD and early EAC, with outcomes comparable to esophagectomy.

Endoscopic evaluation and multidisciplinary approach

Patients with HGD and early EAC should undergo further evaluation at a high-volume tertiary center, in a multidisciplinary setting, by providers who have expertise in this entity. A multidisciplinary approach is a key factor in managing these patients with close collaboration between the endoscopists, surgeons, and gastrointestinal pathologists. The endoscopist should have training and expertise in a comprehensive array of endoscopic technologies and interventions that may be required for multimodal management of dysplastic BE and EAC ( Boxes 1 and 2 ). The ability to manage immediate and delayed procedure-related complications and the discipline to follow protocol-driven care cannot be overemphasized. Meticulous endoscopic evaluation and rigorous adherence to data-driven guidelines achieve the best patient outcomes.

- A.

Tissue acquisition

- 1.

Regular forceps biopsy, modified Seattle protocol

- 2.

Jumbo/multibite forceps biopsy

- 3.

Wide area transepithelial sampling

- 4.

Cytosponge

- 5.

EMR (pathologic staging possible)

- 6.

ESD (pathologic staging possible)

- 1.

- B.

Endoscopic imaging

- 1.

Chromoendoscopy

- 2.

High-definition white light endoscopy

- 3.

Narrow band imaging, Fujinon intelligent chromoendoscopy, i-scan

- 4.

Endoscopic ultrasound

- a.

Miniprobe

- b.

Dedicated echoendoscope (radial or curvilinear)

- a.

- 5.

Confocal laser endomicroscopy

- 6.

Optical coherence tomography

- 7.

High magnification endoscopy

- 1.

- A.

Endoscopic resection

- 1.

Endoscopic mucosal resection

- a.

Single Band EMR

- b.

Multiband mucosectomy

- c.

Widespread-EMR

- d.

Complete Barrett’s eradication

- e.

Cap-assisted EMR

- a.

- 2.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection

- 1.

- B.

Endoscopic ablation

- a.

Radiofrequency ablation

- b.

Cryotherapy

- i.

Liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy

- ii.

Carbon dioxide cryotherapy

- iii.

Cryotherapy balloon device

- i.

- c.

Photodynamic therapy

- d.

Laser

- e.

Argon plasma coagulation

- f.

Multipolar electrocoagulation

- a.

An expert gastrointestinal pathologist should confirm the diagnosis of HGD or EAC. Repeat tissue sampling should be considered when there is doubt, often with adjunct modalities like wide area transepithelial sampling and/or in vivo advanced imaging for confocal endomicroscopy, optical coherence tomography to minimize the chance of diagnostic error, which may lead to suboptimal or unnecessary interventions.

Initial staging and endoscopic therapy options for dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma

Role of Endoscopic Resection

A variety of endoscopic therapeutic modalities are available for the management of dysplastic BE (see Box 2 ). Resection techniques like EMR and ESD provide significantly more tissue for analysis than a biopsy sample. ER helps with tumor staging and can often be a minimally invasive, curative intervention when low burden neoplasia is encountered in the esophagus. As such, ER can play both a “diagnostic” and a “therapeutic role.”

EMR is indicated for resection of nodular lesions in BE, short-segment dysplastic BE, early superficial (T1a) EAC (limited to the muscularis mucosa without lymph node or distant metastasis), and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. ESD can also be used in the above-mentioned situations and may be preferred for resection of larger (>2 cm) lesions and more widespread areas of dysplasia or neoplasia.

ER provides information that complements other staging modalities like endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and cross-sectional imaging. In fact, ER can be the final diagnostic step in the endoscopic evaluation of HGD and EAC in BE. If only HGD or intramucosal carcinoma (ImCa) is found at ER, then computed tomography (CT) and PET have a low yield for metastatic disease. EUS has limited to no value in the setting of BE with HGD alone.

EUS can help detect tumor depth and local lymph node metastasis, although its accuracy varies by stage of tumor. CT and PET-CT are more useful in diagnosing regional and distant metastases in T1b (tumor invading into the submucosa) or higher-stage esophageal malignancies.

The risk of lymph node involvement or metastatic disease is low in patients with EAC limited to the muscularis mucosa with no lymph-vascular invasion, negative deep margin, and well to moderately differentiated (G1 and G2) tumor biology. It is in this subgroup of patients (pT1a + favorable histologic features) whereby ER provides the maximal chance of a durable curative intervention.

If ER reveals T1b disease (or if poor histologic features are present in a T1a lesion), then surgery is recommended because of a high (up to 30%) risk for subsequent lymph node metastasis. Because of this significant change in treatment approach in T1a versus T1b lesions, it is imperative to accurately diagnose, stage, and treat patients who are candidates for curative endotherapy. ER enables us to do exactly that.

Endoscopic mucosal resection

Since its inception in Japan for the management of early gastric cancer, EMR has been successfully applied to the treatment of esophageal, duodenal, and colonic neoplasia. The assessment of the depth of invasion of the lesion is a key factor before considering EMR due to the increased risk of lymph node involvement with infiltrating lesions. This increased risk can be assessed based on the endoscopic evaluation of the target lesion (“nonlifting” sign with saline injection) and also by performing EUS before EMR.

The risk of lymph node involvement in the case of EAC depends on the depth of invasion and tumor stage (<5% in T1a lesions and up to 30% in T1b or higher stage lesions or lesions with lymph-vascular invasion).

Various tumor classification systems have been developed based on endoscopic appearance of the lesion ( Boxes 3 and 4 , Table 1 ). In the Vienna classification, there are 5 categories of esophageal dysplasia/neoplasia. The Vienna classification is the most commonly used classification in clinical practice in the United States.

Type I lesions are polypoid or protuberant and are subcategorized as:

- •

Ip: Pedunculated

- •

Ips/sp: Subpedunculated

- •

Is: Sessile

- •

Type II lesions are flat and are further subcategorized as:

- •

IIa: Superficial elevated

- •

IIb: Flat

- •

IIc: Flat depressed

- •

IIc+IIa lesions: Elevated area within a depressed lesion

- •

IIa+IIc lesions: Depressed area within an elevated lesion

- •

Type III lesions: Ulcerated

Type IV lesions: Lateral spreading

- •

Type 0-I lesions: Polypoid and subcategorized into:

- ○

Type 0-Ip: Protruded, pedunculated

- ○

Type 0-Is: Protruded, sessile

- ○

- •

Type 0-II lesions: Nonpolypoid and subcategorized into:

- ○

Type 0-IIa: Slightly elevated (elevation of lesion above the mucosa <2.5 mm)

- ○

Type 0-IIb: Flat

- ○

Type 0-IIc: Slightly depressed

- ○

- •

Type 0-III: Excavated (ulcer)

| Category 1 | No neoplasia/dysplasia |

| Category 2 | Indefinite for neoplasia/dysplasia |

| Category 3 | Low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (low-grade adenoma/dysplasia) |

| Category 4 |

|

| Category 5 |

|

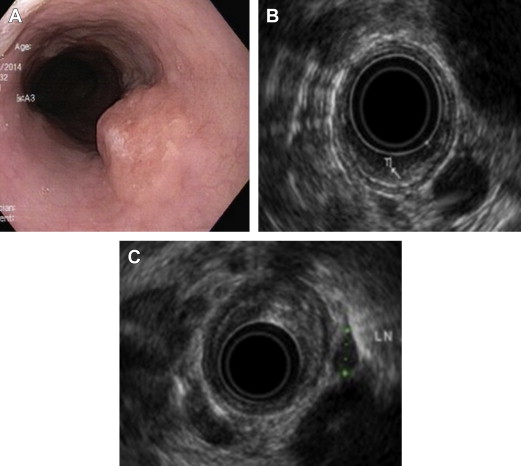

Utility of endoscopic ultrasound before endoscopic mucosal resection

High-frequency probe EUS (20 MHz, 30 MHz) can identify the mucosal (m1, m2, m3) and submucosal (sm1, sm2, sm3) esophageal wall layers in detail. A recent systematic review evaluating the risk of lymph node metastases in BE patients reported virtually no risk of lymph node metastasis in the setting of HGD and an overall risk of 1% to 2 % in patients with ImCa. Factors that predict the risk of node metastasis are as follows :

- 1.

The depth of invasion of the tumor (sm1 and deeper)

- 2.

Tumor diameter greater than 3 cm

- 3.

Presence of lymph vascular invasion on ER specimen

- 4.

The degree of differentiation of the tumor (poorly differentiated or G3 tumor biology more likely to metastasize).

The reported incidence of lymph node metastases has been 9% to 20% in patients with sm1 tumors and as high as 24% to 50% in patients with sm3 tumors.

EUS is widely used for locoregional staging of esophageal tumors but its role in tumor staging of BE with HGD or EAC is unclear. High-frequency miniprobes can be used for pre-EMR staging, but these cannot satisfactorily evaluate nodal disease.

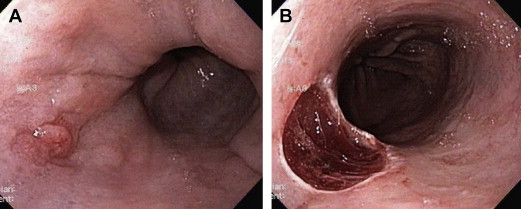

Although some studies report limited value for EUS in superficial lesions once an expert endoscopist has estimated the tumor depth, other reports have shown EUS to have a high negative predictive value for the absence of nodal disease in EAC, while still others have identified lymph node metastases in up to 20% of such patients (see Fig. 1 A–C ).

Thus, EUS can be considered in conjunction with EMR if there is any concern for lymph node metastasis or if the tumor has any high-risk features, as discussed above.

Endoscopic mucosal resection

Indications

EMR is used for the superficial focal or circumferential resection of a BE nodule or visible lesion for diagnostic or therapeutic intent or for short segment Barrett’s resection.

The JSGE have described criteria for lesions in Barrett’s with HGD that are considered suitable for EMR :

- a.

Lesions 2 cm or less in diameter in size

- b.

Lesion involving less than one-third of the circumference of the esophagus

- c.

Lesions limited to the mucosa (ImCa)

However, recent studies have shown successful resection of larger lesions and also complete Barrett’s eradication with EMR as a safe and effective treatment option for BE with HGD/ImCa. Studies have shown no significant difference in cumulative 5-year survival in patients undergoing EMR and ablative therapy for EAC when compared with esophagectomy. Risk of stricture formation is higher when the resection involves more than three-fourths of the circumference of the esophagus.

Patient and procedure preparation

EMR can be performed safely under moderate sedation or general anesthesia. The latter is preferred in high-risk patients, in difficult to sedate patients, or when a prolonged procedure is anticipated. High-definition white light examination (HD-WLE) combined with electronic chromo-endoscopy (eg, narrow band imaging) is essential to achieve a high-quality examination. In addition to the EMR tools, some other accessories that may be needed are specimen retrieval nets, coaptation/coagulation forceps for hemostasis, and endoclips for bleeding control or closure of microperforations.

Endoscopic mucosal resection techniques

Band-Ligation Assisted Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (Suck-Band-Ligate-Resect)

Single band resection technique

The traditional method of “suck band ligate and resect” involves resection of the target lesion using a standard variceal band ligator without prior submucosal injection. The lesion is suctioned into the banding device and a band is deployed across the captured tissue. The band captures the mucosa and superficial submucosa but typically not the muscularis propria. After creating a “pseudopolyp,” the endoscope is withdrawn and the banding device is disassembled. The endoscope is reinserted and, using a standard electrocautery snare, the lesion is resected either above or below the band ( Fig. 2 A, B ).